On the threshold of the twentieth century, the writings of Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860) were among the most important guides to the landscape of the psyche. His doctrine of blind, irrational will that controls everything and turns life into a never-ending cycle of restless exertion and weary satiety contained both a challenge and a consolation that appealed to a number of female poets: they were not, then, the only ones who had wrestled with the world’s will.

Women found it particularly difficult to feel at home as artists in the late Romantic period. Schopenhauer showed them that the individual will could be tamed even if the world’s will remained evil. His three methods of obtaining relief could be combined with each other. The first method was a classic female approach: Have compassion for others and your own suffering will be more bearable. The second method was devotion to artistic creativity and experience, and the third method was asceticism. Thus, the path to inner peace was to exploit the strength of the will, the force of desire, as the Freudians would later say. “Teach the fire’s hearth to deny its own true nature”, Ann Cederlund wrote in “The Sick Man’s Prayer”, one of many poems by women about the longing for snow for the heart, cold for the feelings.

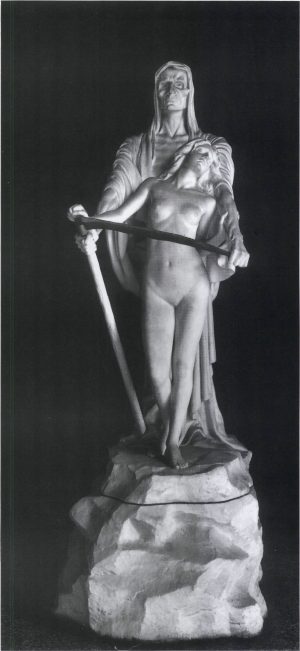

Chosen and Impassioned

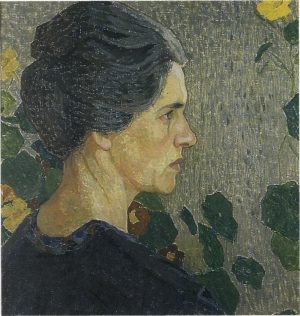

Jane Gernandt-Claine (1862-1944) attended the University for Women Teachers in Stockholm along with Selma Lagerlöf, Anna Maria Roos, and Alice Tegnér, but she travelled extensively with her husband, who was a French diplomat. Her writing, which consisted of five short story collections and twelve novels, in addition to poetry, was her link to Sweden. Ever since her debut in 1893, the topics for her prose had come from other countries. But she won the Bonnier Prize in 1908 for Dikter (1908; Poems).

Gernandt had to drop out of the University for Women Teachers due to illness. Dependent on her father and without career plans, she felt aimless. Tutoring did not offer much of a future, nor was she getting very far with the opera lessons she was receiving from Signe Hebbe, whose mother Wendela was a journalist and author. For a while she acted at the Swedish National Theatre in Helsinki. Hebbe’s friend Ellen Key introduced her to Albert Bonnier, whose publishing house brought out her first book, Fata Morgana och andra berättelser (1893; Fata Morgana and Other Stories). After meeting explorer Jules Claine in Paris shortly afterwards, she gradually made France into her second home.

Like Lagerlöf, Gernandt-Claine never doubted her calling in life. Even as a child, she felt as though she had been chosen “from above,” and her autobiography recounts an eight-year-old’s struggle with existential questions: What is the purpose of life? Why sit there and play when you are going to die one day? She collected stories about Sappho, Cleopatra, Saint Birgitta, and other historical figures, convinced that she shared something essential with them. All of Gernandt-Claine’s writing reveals a strong commitment to women while portraying heterosexual love as the ultimate goal and greatest pleasure that life has to offer.

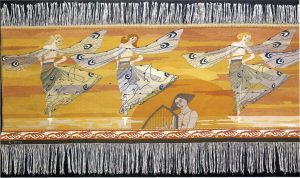

Both Aphrodite and Calypso claim the nettle as a symbol of women’s experience of love in Gernandt-Claine’s book of poetry Till Afrodite (1910; To Aphrodite). Only a woman and a poet can grasp the beauty of the nettle as it burns her. Calypso experiences the searing wound of loss when Odysseus longs to leave her, or literally does so. In “Ermia”, however, the woman is silent and thoughtful while Aristotle wonders uneasily what worlds she is hiding in. She does not answer, but simply smiles.

Gernandt-Claine found Schopenhauer’s theories to be deeply satisfying when she was dealing with an early disappointment. According to him, people are driven more by their desires than by their intellect. Will, the unconscious pursuit of satisfaction, is evil because it persuades us that true happiness is possible. The short story “Kvinnohämnd” (Women’s Vengeance) in Det främmande landet (1898; The Foreign Country) is about the transformation of a woman’s desires into an act of creativity. In a manner reminiscent of a writer, she manipulates those around her to bring about a horrible retribution for her husband’s betrayal.

Gernandt-Claine never doubted Schopenhauer’s contempt for women. As deeply as his misogyny offended her, however, his pessimism steeled her heart: “He put me on such intimate terms with bitterness that no setback has ever caught me by surprise.” Mitt vagabondliv (1929; My Vagabond Life).

“I read Darwin, Spencer, and Haeckel, which left me so spiritually exhausted that I sought solace in the writings of Schopenhauer. He represented an epoch in my life, just like marriage does for other young women. He himself couldn’t live without women. And when I read Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung I would get up and walk back and forth under the glittering stars, my brain bathed in a sensation of intellectual bliss that belied my twenty-six years. Schopenhauer and I were made for each other, I confided to myself, and I would always be grateful to him.” Mitt vagabondliv (1929; My Vagabond Life)

If Schopenhauer was Gernandt-Claine’s spiritual father, Saint Teresa of Avila was her mother, and both of them showed her the way to the nooks and crannies of the soul. She shared not only Saint Teresa’s humour, thirst for knowledge, and devotion to writing. Her autobiography also describes revelations, worthy of a true mystic, that she experienced as a child and adolescent. Whereas Schopenhauer rebelled against the academic world, Saint Teresa had similar feelings about the Church.

A recurring theme in Gernandt-Claine’s works is women’s silence, like that of a clam or mollusc. The poetry collection En rosenslinga (1913; A Rose Wreath) features a childless poet who identifies with St. Teresa and the need to muffle so much of her heart, as well as with a woman who sacrifices herself to her husband’s military career.

Her last fiery contribution to the women’s struggle was her book of poetry Hetär (1931; Hetaera). Instead of her name, the title page said simply “Poems by a Rhymer”. The protagonist of the title poem is the flute-girl in Plato’s Symposium who is dismissed from Agathon’s banquet so that the men can extol Eros undisturbed. “No women’s fragrance do we need”, Eryximachos says in Hetär. “No frills and fancies / stir our heart, only the fruit of manly creed. / I ask then that this wench depart.”

Lend Coldness to Her Heart

Anna Cederlund (1884-1910), a tubercular young woman from the island of Gotland, was among the students at Rostad University for Women Teachers in Kalmar – founded by education reformer Cecilia Fryxell for “simple girls” – in the autumn of 1902. The school provided her with breeding as well as training. Both teachers and students envisaged a glorious future dedicated to their noble profession. But Cederlund was unmanageable. They complained that she was too gifted and spontaneous, perhaps unsuitable for the career that had been staked out for her. Her dialect was regarded as an obstacle; something needed to be done about it if she was going to fit in.

She was highly critical of herself as well. She had her own ideas about teaching but lacked the strength to put them into practice, and she later had difficulty handling a classroom.

As a young schoolteacher in the Dalecarlian parish of Marnäs, her fondness for Social Democratic ideas hardly made her more popular. Her spiritual guide was the idealist and social critic John Ruskin. She read his books and argued for the importance of beauty in everyday life. Erik Hedén, her brother-in-law and the son of a pastor, filled her with revolutionary enthusiasm. He was an influential cultural journalist with the social democratic newspaper Social-Demokraten, the young people’s newspaper Fram (In Front), and Tiden (Time). He assigned Cederlund to write reviews. He and Klara Johanson contacted the cultural magazine Ord och Bild (Word and Image) and the newspaper Stockholms Dagblad, which published a number of her poems. By that time, Cederlund’s tuberculosis had progressed to the point that her impending death was the biggest source of interest. Her book of poetry Höst (1910; Autumn) appeared only a few days after her death in 1910 and was judged accordingly.

What were her bitterness and pessimism all about anyway? They had nothing to do with death, Örjan Lindberger writes in the 1961 edition of the book, but stemmed from the obstacles she faced when trying to use her gifts for the benefit of others. But the poem he quotes as evidence speaks to a more profound despair that nobody is going to pine for what she has to offer. She feels worthless and rejected.

Your debt – the adult’s proud debt to the world,

to help others as you have been helped –

you were unworthy of paying it, so hold onto it

with the consolation that your work will not be missed.

This first of “Two Sonnets” exudes a keen sense of irony and ends with an exhortation to the soul to speak out about life, so that nobody will be led to believe “that you expected more from your fate than what it so miserly offered.”

Vilhelm Ekelund, a poet whom Anna Cederlund admired, wrote that Höst reminded him of his own ability to see through the unsustainable and dubious nature of everything that informs the mind and heart. “Din blick” (Your Gaze) – presumably written to Ester Nyrén, Cederlund’s colleague and the only one who could penetrate her gloom for many years – contradicts his assessment: “Holy, holy / radiated the gravity of life from your gaze” when the world lay in waste, “and my bitter, humiliated heart / rejoiced again at beating in a human breast.”

Cederlund lost her mother when she was a young child and was raised by her paternal grandparents on a Gotland farm. The grief followed her throughout her childhood, which she spent mostly in the company of women, particularly at school. The students had crushes on the schoolmarms, and deep friendships arose. Uncertain about the nature of her feelings, Cederlund jilted a beloved friend and never forgave herself for it. She took her relationship with Nyrén with more equanimity, gratefully acknowledging that they had accepted their importance to each other. The last poem in the book testifies to a powerful force outside herself, that of love. Her vision of the good life was to work in the same room as her beloved. One of her letters describes her sitting by a window and waiting for Nyrén to arrive. It strikes her that the greatest peace and joy life has to offer is “to be fond of another person.”

Centaur in Pursuit of a Self

“Beatrice-Aurore”, the melancholy love ballad about the long-dead damsel who still eludes her suitor in his dreams, is by Harriet Löwenhjelm (1887-1918). Perhaps it is not so remarkable for a woman to write a poem that features a male narrator, not even when the word “I” appears nine times in eight stanzas. But if the voice of a female artist is nearly always that of a man, the question asserts itself: Who was she?

Löwenhjelm is known for playing the jester and hiding behind various disguises. She speaks seriously more often than not, but almost always with a wry expression on her face. Just like Beatrice-Aurore, she cries: “Catch me then”, and slips behind a door. Those who read only her posthumous poetry might find the wry face a bit trying, even if they know that the jester is part of a tradition. Löwenhjelm knew where her poses came from: the first link in the chain was commedia dell’arte; her favourite character was the Pierrot the buffoon. One of her predecessors was the poet Carl Michael Bellman, who took over the stock characters and transplanted them to the backstreets of Stockholm. Father Mowitz, a Bellman character with a double bass on his back, a French horn under his arm, and a bottle of liquor in his pocket taught Löwenhjelm to banter – he also died of tuberculosis and served as her companion in distress.

Like Bellman, she sought to transfigure the horrors of death into beauty and resonance:

Catch me. – Hold me. – Caress me gently.

Embrace me tenderly for a brief moment.

Weep a little – for such weary facts.

Watch me affectionately as I sleep a while.

Don’t leave me. – I know you want to stay,

stay until I must go.

Lay your beloved hand on my forehead.

For a few more minutes we will be two.

This well-known poem, which Löwenhjelm wrote towards the end of her life, evokes the short breaths of a consumptive. Soon she will know where the journey leads: “Tonight I shall die. – A flame flickers. / A friend sits and holds my hand.” Still it is not too late to play with words and postures. The gently singsong rhythm so characteristic of her poetry is constrained by the pauses of her tired voice, and the “weary facts” season the heartfelt, tearful ambience. The reader can imagine Elsa Björkman as the friend who tenderly embraces her dying friend. Once Löwenhjelm sensed that the end was near, she was no longer content with her earlier expressions of yearning: “My darling, do you think it will be much longer before you come home?” (a letter to Elsa in Moscow, 8 April 1918). Instead she telegraphed to Björkman, who took hospital trains and military convoys through Poland and Berlin to say goodbye and see to it that her manuscripts were published. Two days after Björkman arrived, Löwenhjelm died holding her hand.

In 1914, Harriet Löwenhjelm wrote to Elsa Björkman from the Romanäs Sanatorium about a remarkable patient she had met.

“Carnality in all its forms is her greatest interest, but she doesn’t give a whit for it in her own life. If she falls in love with someone, it’s on a rather ethereal plane.” The patient had described in detail how she would react if a coarse soldier tried to rape her.

“Enough about that. Don’t believe for a second that I voluntarily pushed this hearty dinner away. But life has taught me that if something doesn’t want to stay, it’s best to let it go.”

Her oeuvre consists of twenty-two diaries with vignettes, etchings, and drawings, book manuscripts, letters, poems, and the underlining in her copies of Kierkegaard’s books.

A handwritten newspaper that she put together at the age of sixteen contains “My Confession”. A stately woman captivates the poet’s soul:

When I see you standing there so proudly and so mutely

I want to kneel at your feet and confess my love

but then it’s as if something held me back.

And all at once I’m silent and embarrassed and dumb.

That autumn she and her father, Colonel Gustaf Löwenhjelm, embarked on the biggest journey of her life, to India and Ceylon, where her older sister lived. That is where she first encountered the great idols and silent Buddhist monks who later personified potentates or perhaps only inaccessible mortals.

The vignettes in her diaries are more suggestive than the words in exposing the complexities of her life. Her “logbooks” were always out for anyone to peruse, and she often read out loud from them. The pictures, or rather doodling, next to the words showed over-exerted men in captivity or submission. A recurring theme is the thin figure who kneels on the floor in front of a heavy, unperturbed idol perched on a high pedestal.

In her 1947 biography of Löwenhjelm, Björkman asked herself where those obvious guilt feelings, which mounted to anxiety, came from. At a point when their friendship was on shaky grounds, Löwenhjelm wrote to Björkman: “You are the cross I have been given to bear / every day, albeit a cross of sugar candy.”

As a teenager, long before she became ill, Löwenhjelm had the bright idea of penning a will in which she left Björkman “the centaurs of spring”. Did she think that her friend could understand better than anyone else what it was like to be two creatures in one body? Writing in 1947, Björkman said that she still felt too close to the events of her childhood to objectively explore the roots of Löwenhjelm’s depression. Her memoirs Jag minns det som igår (1962; I Remember It Like Yesterday) points out that teenagers are frequently unsure of their sexual orientation and that artists tend to mature later than other people.

Löwenhjelm’s clique at the Anna Sandström training college had learned that heroines prepare themselves for a future more challenging than marriage. Björkman remained at the Royal Swedish Academy of Fine Arts and did not marry until the age of thirty-three. Elsa Brändström (1888-1948), who was in the same class, convinced Björkman to accompany her to Russia, where they helped prisoners of war for several years. The “Angel of Siberia” married at forty-one after a long career that she recounted in her memoirs Bland krigsfångar i Ryssland och Sibirien (1921; Among Prisoners of War in Russia and Siberia).

Disappointments associated with her calling in life no doubt contributed to Löwenhjelm’s depression. A poor student, she was dismissed from the Royal Swedish Academy of Fine Arts (the Yuckademy as she called it) after her probation year. The instructors did not like her demeanour; she grew flippant and rowdy, showed up late, turned her back on the models and sang. “Imagine being a chap”, she wrote to a cousin in 1914. “I have all the talents of a man. I don’t feel at home in my own skin and I lack the stamina to accomplish anything.”

Of the many women who worked and associated with Löwenhjelm at Harriet Sundström’s studio, Vera Nilsson and Siri Derkert achieved considerable renown, while a number of others became both authors and graphic artists: Mollie Faustman (1883-1966), Elisabeth Bergstrand-Poulsen (1887-1955) – who documented women and their lives in the province of Småland – Gertrud Lilja (1887-1984), and Elsa Björkman-Goldschmidt (1888-1982). Karin Ek was a member of the clique at the Anna Sandström training college.

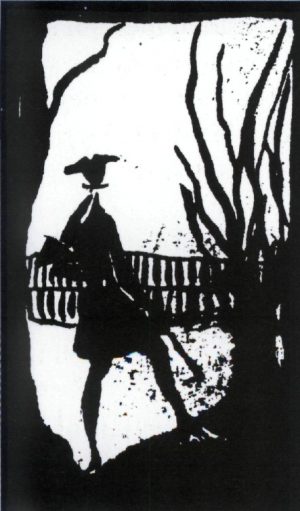

On her deathbed, she left her manuscripts to Björkman and her cousin Christer Mörner for possible publication. She had already printed fifty copies of Konsten att älska och dess följder (1913; The Art of Loving and Its Consequences)for her friends. Her family did not expect her poetry to attract much attention beyond the people who had known her, and proceeded accordingly with the first posthumous edition. For instance, “Plaisir i Paris” (Pleasure in Paris) was left out for the sake of decency. Her father was particularly put off by the youth’s assurance that love for a day is more gratifying than the object of his affections could accept. Löwenhjelm’s illustration shows an extravagantly dressed young man and a woman with feathers in her hat. She turns around and leaves.

A Missionary with a Worldly Calling

Ur svenska dikten (1921; From Swedish Poetry),a major three-volume anthology by Karin Ek (1885-1926), was the successor to the work of literary historian Karl Warburg. His Svenska sången: Ett urval af svenska dikter från tvenne sekler (1883 and 1910; Swedish Song: A Selection of Swedish Poems from Two Centuries; Eng. tr. Anthology Of Swedish Lyrics From 1750 to 1915) had been out of print for a number of years. According to Ek’s upbeat preface, the anthologies were intended for the schools but both she and Warburg hoped to attract general readership as well. Her dearest wish was to convey her love for poetry, a “source of universal happiness.”

However, the motto that appears at the beginning of each volume tells a more subtle tale: “Song grows out of sorrow but brings a joyful morrow.” Her own song grew out of both passion and suffering; poetry was her lifeline.

One might expect that she would have gone out of her way to include women poets, but she actually left out two whom Warburg had included despite the considerably narrower scope of his anthology: Thekla Knös and Euphrosyne (the pseudonym of Julia Nyberg), both from the nineteenth century. Critic Ellen Kleman grumbled that Ek had not found room for two of her contemporaries, Jane Gernandt-Claine and Anna Cederlund. Instead she chose Gustaf Ullman, Sigfrid Siwertz, Vilhelm Ekelund, and Anders Österling, all of whom had started off somewhat earlier.

Hedvig Charlotta Nordenflycht and Anna Maria Lenngren, along with novelists Fredrika Bremer and Selma Lagerlöf, are the only women whose work appears in Ur svenska dikten. Ek never had the chance to carry out her plan for a new and improved edition. She died of cancer at the age of forty-one.

Because she passed up her own writing, it was often overlooked in later years when the best and most important Swedish poetry was selected. Elisabet Hermodsson’s anthology Kvinnors dikt om kärlek (1978; Women’s Poetry about Love) finally included an exultant love poem that she had written. Tom Hedlund’s anthology Svenska lyriken från Ekelund till Sonnevi (1978; Swedish Poetry from Ekelund to Sonnevi) follows a tradition by publishing two poems that Ek had written under the shadow of death: she achieved renown among male critics as a dying woman.

But Ek deserves a place in literary history not for her death, valour, or self-restraint, but for her boldness and intensity. She was faithful to love and poetry, and she was accustomed to, almost friends with, death long before she fell ill. She took several years off from school to care for her mother Florence, an Englishwoman, who died in 1904 at the age of forty-two. Not surprisingly, perhaps, she confided to her diary a couple of years later that half her life might be over. Her first book of poetry, with her maiden name (Lindblad) on the cover, was published in the year of her mother’s death.

Dikter (1904; Poems) is the manifesto of a young woman and an enthusiastic tribute to nature, country, parents, and God. Don’t brood, she says to the reader – whom she calls her weeping brother – in “Till strids!” (To the Ramparts!). Fight for everything you find worthy of admiration and love, “and stand upright as a man / And even if you should fall / what does that matter? Rise up again.”

Ek left such hopeful and naive poetry behind in her adult years, but nevertheless looked back at childhood as an idyll, a time of flowers and ideals without attachment or anxiety.

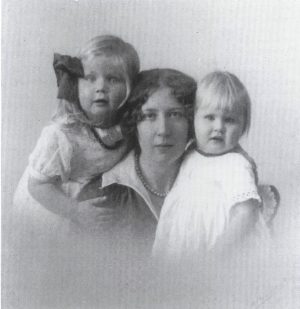

Den kostbara hvilan (1914; The Costly Repose) was her next book. She was married and had given birth to a boy, who lived only a few months, followed by two girls. Her parents were dead; she had moved to Gothenburg but wrote about Stockholm, so neither city could fully accept her as its poet.

What did the other women think about Ek’s poetry? Weary of “rookie versifiers”, Klara Johanson was enchanted by Den kostbara hvilan and wrote that “to us a poet is given”. According to Johanson, Ek’s poetry exuded modern elegance with its “rhythmic capriciousness, boldly condensed idiom, solemn stylisation”, and passionate, compelling language. Critic Ellen Kleman thought that Ek was a top-notch poet and had unjustly excluded herself from her own anthology, Ur svenska dikten.

“You were filled, like a field of sun-dried grass, / For a moment with burning fire”, Lagerlöf wrote in the poem that Ek chose for Ur svenska dikten. Ek countered in 1914 with “My soul is scorched like a burn-beaten land” and “Like a clam lodged within its hard shell / my soul closes wearily upon itself.” The costly repose is the dearly acquired stillness that descends when the sparks have gone out and the embers are dying. Two tendencies can be discerned: heavy, succulent nostalgia and the allure of nature:

Louder than the voice of the crickets, my soul cried in desolation,

higher than the birds in the trees, the flower of my passion grew;

now my soul is like a blade of the bowed, rustling sedge,

dry as the stem of the thistles, quiet as the cricket’s song.

The classically trained poet impressed critics and readers alike with her adroit idiom. The metre of this particular poem is the distich of antiquity: each couplet consists of a hexameter and a pentameter.

Kleman referred to Fredmansgestalten (1915; The Fredman Character), a highly original and deeply personal book of essays, as a “poem of literary analysis”. Sten Selander, however, thought that it contained “inarticulate shrieks of rapture”. He took the opportunity to pass judgement on women in general:

“I have difficulty imagining women as critics in any way, shape, or form. The cold detachment that constitutes half (though not necessarily the most attractive half) of the critical sensibility is repugnant to their hearts.”

(Ord och Bild, 1927).

She longed for Humlegården Park, white and blissful in May, for Stockholm’s waterways: “Like the emerald of your depths, my heart slowly turns black / as the days bow to spring in the ascending light.” The moon, the mist coming in from the sea, and the “outstretched wooden arms” of her window transform her nights into crucifixions: “O tree of pain that night after night / stood sentry for my wary soul” –from “Tecknet” (The Sign). In “Vingarna” (The Wings), day gives way to night and the wings of death flutter through the room. The threat now comes from the light; the wings bear repose under their folds: Hold them still a while longer, the woman pleads, “for here is peace”.

When nature consoles, its boundary with the human world grows diffuse. A mountain spring opens its arms to the soul in “Ett öga” (An Eye):

Oh spring, bottomless and clear, I lower my queasy longing,

drop my anxiety into you like heavy gravel.

Your kind, lucid gaze seeks my eyes through the darkness.

“Jorden” (The Earth) describes a kind of fusion, a sexual act. The woman longs to caress and embrace sea-swept rocks, hot from the sun; she plunges her hands into the sand and vegetation.

I clasp the earth, hungering

to feel the warmth of all its life,

to be one with its murky soul.

Den kostbara hvilan talks about women’s betrayal, not men’s. Impossible love, pulsating with desire but doomed by class differences, is the motif of Ek’s novel Gränsen (1918; The Border).

But the book is also about self-awareness. Agnes – an allusion to shipwrecked hope in August Strindberg’s Ett drömspel (1901; Eng. tr. A Dream Play) – wants to love the object of her affection the way she loves the grass, sand, and mountains, and her mind tells her that she cannot afford to hesitate. She should merge with him completely, “lose herself in his thoughts, feelings, and will”. Her inner struggle and the shame that her prejudices stir in her breast are portrayed with great delicacy, though somewhat compromised by erudite literary references.

After reading Elin Wägner’s novel Kvarteret Oron (1918; The Anxiety District), Karin Ek sent Wägner some fan mail:

“Your stories about self-supporting women, all the ‘quiet ones,’ are deeply poignant. How fortunate you must feel to be able to give these mute women a voice.” Wägner replied by sending her novel Åsa-Hanna (1918) to her admirer.

The book of poetry Idyll och elegi (1922; Idyll and Elegy) elaborates on some of her previous themes, the contraction of life to a dichotomy between the human condition when sexuality and betrayal were still unknown and the hollow legacy of the Fall when not even loss can be truly experienced. In “Elegi” (Elegy), the heart no longer knows the fury of desire:

And the grass that wafts

its wild smell of nectar,

that prepared our sanctuary

and encircled our tents with loveliness…

how indifferently it flutters in the night air.

Ek’s view of childhood as a Garden of Eden and children as a blank slate reflected a tradition that lived long into the twentieth century.

The widely acclaimed “En liten grav” (A Little Grave) speaks volumes about her attitude towards children. The first part is about her dead son, who hides his head in the friendly earth, “ protected from icy squalls”. In the second part, Christmas Eve has arrived and his siblings are playing. They sing and dance around the tree: “they no longer remember that you are asleep / out there in the murmuring night”. Only the mother recalls the infant in his snowy shirt.

Such thoughts prevented Ek from empathising with living children and their cares, and her poetry describes the griever’s inability to be a good mother. The children she writes about are rarely individuals, but metaphors for life before passion and affliction. The first-born also serves as a link to the approaching night, when the singing of children will not disturb her sleep. “En hel lång natt” (A Whole Long Night) appears in her last book, Död och liv (1925; Death and Life). After several stays at the radiation department in Stockholm, she knew that the end was near. She had no doubt that the child who planted bulbs would wander jubilantly towards fields of narcissi and hyacinths the following spring ,as she lay in her hidden grave. In “Verser i sjukdom” (Verses in Illness), she wants to hold a child at arm’s length so that the turbulent river of death’s kingdom will not frighten “his innocent blood”. Her awareness that the child may suffer harm is replaced by the consolation that he can remain protected and “innocent” despite her own demise.

Död och liv contains many poignant testimonies to both the preciousness of existence and the comfort that comes with letting go of it. Ek’s poems of passionate rendezvous that dispel anguish if only for a moment carry at least as much power. “Till—-” (To—-), presumably dedicated to her friend and lover Pär Lagerkvist, is a kind of dialogue with his play Sista mänskan (1917; Eng. tr. The Last Man), and possibly with his poem “Som ett främmande skepp min själ sökte hamn” (Like a Foreign Ship, My Soul Put into Port) – from Den lyckliges väg (1921; The Way of the Happy One).

She addresses the lonely man, who cries across the eternal expanse of snow and finds only homelessness in the soil: “See the man – who searches in anguish / for his cane and staff”. She has a message to the one who struggles with “God’s mighty life and death”. You shall find your shelter from the storm, it greets you in peace, she assures him. “Flaming soul, you will reach it – / when evening falls”.

This was in the early 1920s, when Ek’s relationship with Lagerkvist was most intense. Only their closest friends knew about it, and the scholarship about him never caught wind of the secret. Her husband Sverker, who was among the early promoters of Lagerkvist’s poetry, stated that none of her love poems were about him. Lagerkvist may have been thinking about the author of Den kostbara hvilan when he claimed that he paid more for love than his smiling sweetheart: “Life must give me costly things, a sea of passion to be feared”. The poem is from Hjärtats sånger (1926; Songs of the Heart), which appeared the same year that Ek died.

Ek wrote free verse on occasion. By her own admission, however, she despised the form because it allows for unbridled expression. But as “En örörd” (Unmoved) demonstrates, even something as strict as hexameter can overflow. The young woman stands blissfully in the “shower of the seaweed” – the water splashes her knees and thighs. Humanity has not yet fallen. But the narrator knows more about the Fall and about the man’s trembling fingers on the vault of her thighs. The poem, which is from Idyll och elegi, ends with:

Do you know, smiling child – you will soon be like a

dreamer,

your eyes full of night, your lips bloody with lust;

your naked limbs bathed by the golden sea,

the intoxicated gaze of men, Eros’ fiery embrace.#note10

Translated by Ken Schubert