“It is high time that mothers reject their centuries old petrified pattern and stop idolising the Madonna and Child as well as the gray and wrinkled, sorrowing and dejected mother, bent over the wash-basin”, Eeva Kilpi (born 1928) writes in the pamphlet Miesten maailman nurjat lait (1968; The Mad Laws of the World of Men). The radical tone of her article heralds both the change to come in Finnish literature during the 1970s and the transformation that was under way in her own works.

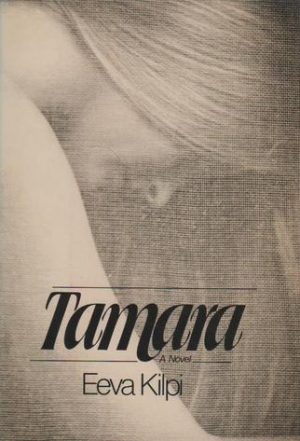

With the collection of poems Laulu rakkaudesta (1972; Songs of Love) and the novel Tamara (1972; Eng. tr. Tamara), Eeva Kilpi becomes one of the leaders of the Finnish women’s literature scene. As early as in the 1960s, she had depicted women and their sexuality, but in Laulu rakkaudesta and in Tamara she goes full throttle and makes the woman the erotic subject. Tamara is an uninhibited, self-expressed woman. She consistently breaks all ethical norms, is unmarried, takes married men for lovers, and harbours no feelings of guilt whatsoever about being ‘the other woman’. The bodies of men are depicted as she, the woman, experiences them, and she names their sexual organs in the same way that men describe those of women. In the sexual act, Tamara ‘creates’ the man and makes him what he is. She has an intense love life and reports about it to the narrator of the novel, an impotent handicapped researcher in linguistic psychology. The constellation of characters is not some simple reversal of accepted gender roles, but a daring attempt to surpass them. The physical and erotically expressive Tamara and her physically pacified, but intellectually expansive, male friend are an expression of apparently incompatible poles that, according to Eeva Kilpi, must be joined for development and love to be possible. Towards the very end of the novel, the woman and the man journey towards the borders of existence and the universe: “For a moment, that which equals me and everything which makes up you in your entirety form a person that isn’t to be found in grammars. The theory of relativity turns a somersault in space. The infinite fills the zero and raises it to a power that is never released. Positive and negative produce a shower of stars.”

Tamara garnered a mixed critical response. The novel caused sensation and debate. With the collection of poems Laulu rakkaudesta, Eeva Kilpi managed to hit both the critics and the public in the heart. Like none before her, she writes about the law of everyday desire. Countering the antiseptic copulations of sexual activism, she pays homage to the human body in all its frailty and incurable fervour. In burlesque turns of phrase and with biting irony, but above all with a good deal of warm-hearted humour, she describes the limits, prejudices, taboos, and sad conventions that continually threaten to hobble love, which in spite of all is indomitable. “Some fine day / we will lie with one another / a lock will snap shut and we will never get loose again, / your worn out joints entangled in my arthritis, / my ulcer next to your heart disease”, is the joking introduction to the title poem, soon to be pervaded by the trust in love’s power that obviously carries these poems: “And with cataracts in the eyes, waiting for a place at a care home / you blindly grope for me, / feeling your way with your hands. / Feel on, dear: / under all these wrinkles is me / this is the disguise life forced onto us in the end, / you my strawberry, my swallow, my flower so fine.”

“The sad thing is that you hardly ever get to read an open and passionate, detailed and reckless depiction of sexual behaviour in literature, and least of all from a woman writer,” one of the characters in Eeva Kilpi’s Tamara (1972; Eng. tr. Tamara) says, and the novel, as well as the poems in Laulu rakkaudesta (1972; Songs of Love), can be seen as a strong bid to rectify this imbalance.

Eeva Kilpi made her debut in 1959 with the collection of short stories Noidanlukko (Moonwort), and during the 1960s she published a number of novels and short story collections in which the pairs of opposites – man and woman, body and intellect, but even more city and countryside – were the mainstay. The high point of her early production, Elämä edestakaisin (1964; Life and Back Again), is about an evacuated Karelian who cannot bear his longing for home. Two years earlier, in the novel Nainen kuvastomessa (1962; The Woman in the Mirror), she depicted a woman who breaks from her Karelian village and its fellowship of women to become a city wife, where her life is filled with activity but emptied of meaning. In the black morality of Rakkauden ja kuoleman pöytä (1967; The Table of Love and Death), her criticism of urban life approaches pure condemnation.

For Eeva Kilpi, the city and modern technology kill not only plants and animals but also people. She has a singular mix of longing for the village and militant eco-activism, and her organic and holistic vision of life is clearly expressed in her writings. In the collection of poems Animalia (1987; Animalia), she describes an absorption in nature that is almost pantheistic. Here, there is no hierarchy between humans, animals, and plants: “Every animal is a subject. / It is the centre point of its own life, / its own defender, / on guard in all directions / like you and I”, she writes. There are no differences, everybody is part of the same whole. “Why not call everybody people”, the young lover asks her beloved in the eponymous short story in Kuolema ja nuori rakastaja (1986; Death and the Young Lover). A tumour is growing in her womb, but she refuses surgery and mutilation. Instead, she uses all the energy left her to ‘turn the world upside down’ by enrolling her students in battling for a society that is not against nature, but sides with it.

In Eeva Kilpi’s texts, mankind discovers its innermost core by opening up to nature and its ongoing cyclical process. Henry David Thoreau’s Walden; or, Life in the Woods (1854) often comes to the minds of critics when they read her works, and just as Thoreau’s transcendentalism does, so Eeva Kilpi’s ecology embraces a strong criticism of society and adds a social reformist dimension.

“With my old dog at my feet I look for a place on the slope where I can bury him. I try to get used to death. After you, my friend, I might take a man, one of those shy allergic ones”, it says on the endpaper of Häätanhu (1973; Wedding Dance), perhaps Eeva Kilpi’s best loved novel. In her works, death is always present, decay built into blooming, and loss integrated in the act of love. There is a great sadness in her stories, but also a strong rage. She makes herself the interpreter of the denied, the accessory of nature, the defender of aged women, and the enemy of technocratic male society. She tells of abandoned landscapes, of the village and the forgotten women; those middle-aged, not so pretty women living life and retaining all their passion and longing.

In Eeva Kilpi’s works the past is always present. The woman is in the middle of life in all senses, but to move on she must, like Anna Maria in Häätanhu, seek out the past. In a transitional stage, between two phases of her life, between two men and two marriages, the stay at the deserted family farm in the midst of nature becomes a rite of passage, where the old finally, like in a natural cycle, can be resolved and wither away to make room for the new. On the last pages of the novel in a symbolic process she buries her old dog, while she regards the oncoming autumn’s “furious and mellow beauty”.

“She knew perfectly well that the new road had been finished that spring. But when she came to the old, between the milestone and the bus stop, she slowed from habit and, turning into the holed, familiar road, she felt that this was exactly how she had wanted to arrive, precisely the same way as always.” These are the opening words from Eeva Kilpi’s widely read novel Häätanhu (1973; Wedding Dance), and the text’s somewhat melancholy yet resolute tone is significant. In her texts, women turn towards the past and towards nature to find a foothold in life.

“Every day is a story”, Eeva Kilpi wrote as early as in Laulu rakkaudesta. The same thought is reflected in her public self-portrait in Ihmisen ääni (1976; Voice of Mankind), and in the diary Naisen päiväkirja (1978; Diary of a woman). Autobiographical material is close to the surface throughout her works. The summerhouse, which is a setting not just in Häätanhu (1973; Wedding Dance) but also in many of her short stories, is situated in Savolax, the location of Kilpi’s own summerhouse, and many of her protagonists bear a striking likeness to herself. During the second half of the 1970s and the early 1980s, she approaches pure autobiography more and more.

After the confessions in Ihmisen ääni and Naisen päiväkirja, she turns first towards her father and then towards her own childhood. The collection of poems Ennen kuolemaa (1982; Before Death) is one long elegy on her father’s wasting-away and death. Occasionally she retrieves the old humouristic tones: “You need not be quite so dead, father / you could drop by once in a while, sit in the rocking chair, / take my hand and hold on to it when we shake hands / just as you used to.” But time and again death shows its implacable face, and there is no cure for grief in Ennen kuolema. In the ambitious Elämän evakkona (1983; Evacuated for Life), Eeva Kilpi returns to her Karelian village and the circle of motifs from Elämä edestakaisin, but with the death of her father as the point of departure. In a number of shattering scenes, the reader follows the protagonist Tauno Kokoo’s gradual dismantling on the path to death. He is a strong man, a former timber trader and elite sportsman, used to making decisions and to winning. But before the cancer takes him away from life he is forced to submit to being put away, rationalised away, and re-evaluated.

Eeva Kilpi gradually approaches the pain points that have always been operating in her works, and her texts become even more precise when it comes to both her attitude to life and her personal background. In 1989 she publishes the first part of an autobiographical trilogy comprising Talvisodan aika (1989; Eng. tr. The Time of the Winter War), Välirauha, ikävöinnen aika (1990; Time of Longing), and Jaktosodan aika (1993; Time of the Continuation War). With these books, she writes the history of WWII from the perspective of women and the Finnish home front. But the trilogy is also about different means of understanding this history. “Hidden in memories still lies the strange clarity of the personal, which the novel hasn’t yet exhausted”, she writes in Jaktosodan aika, and in her autobiographies she opens doors into not only her own memory story, but also those of others. She pits her personal memories against those of her mother, and makes an inventory of the war diaries and war-time newspapers found in archives. She enables the reader’s own memory work while describing her own, and she consistently completes the critique of civilisation that has been the driving force throughout her works, even in her personal story.

As early as 1954-1957, Väinö Linna’s magnificent depiction of the Finnish war years is published, and the domestic wars have played a major role in Finnish literature. The perspective, however, has always been that of the male soldier. Not until the end of the 1980s was history written from a different perspective. In Eeva Kilpi’s autobiographical books, set in Karelia, the war is described through the suffering civilian population, from the women’s and children’s points of view.

Translated by Marthe Seiden