“It was October and misty weather. The woods around Stone Castle looked more gray than green, insignificant and dripping, absolutely quiet. Just Hannafia Alle squatted and crept about. She was gathering mountain cranberries, she snuffled now and again.”

Thus begins the tale of the twelve-year-old Hannafia in Irmelin Sandman Lilius’s fantasy tale Korpfolksungen (1994; The Raven People’s Child) from 1994. The time is the late nineteenth century, the environment the fictitious Finland-Swedish town of Tulavall, where Hannafia and her large group of siblings belong to the poorest of the poor. Hannafia, like many of Irmelin Sandman Lilius’s protagonists, is a girl heading into womanhood. In her social environment working is a natural part of existence: gathering berries, looking after the interminable younger siblings, helping the worn out, careworn mother in the household.

In the realistically depicted woodland, Hannafia meets fantastical beings. She meets her friend the sailor Tuspuru Schando from the magical ship Southwest, and together they find an even stranger creature, an abandoned child of the wild, winged raven people. Hannafia and her foundling are evicted from the parental home and she takes up position as ship’s girl on the Southwest for its dangerous voyage to the Greek Archipelago. The tale of Hannafia turns into a fairy tale, a love story, and becomes a part of the day’s debate about xenophobia and destruction of the environment.

In her book Fru Sola-trilogin. En studie i Irmelin Sandman Lilius’ berättarkonst (1986; Mrs Sola Trilogy. A Study in the Narrative Art of Irmelin Sandman Lilius), Petra Wrede has analysed Irmelin Sandman Lilius’s way of working with multiple temporal planes and several planes of reality. Petra Wrede, on the one hand, points to precursors like Selma Lagerlöf and Zacharias Topelius, whose idealist, anti-materialistic ethos is clearly shared by Irmelin Sandman Lilius, although without the religious involvement. On the other hand, Wrede points to a literary convention within the fantasy genre, which Irmelin Sandman Lilius has both written of as a critic and been inspired by as an author. Fantasy writers often operate with shifts in time and let supernatural elements infiltrate everyday life.

A third element is Irmelin Sandman Lilius’s strong, almost pantheistic, acknowledgement of nature and her intuitive conviction that the supernatural exists.

A Multi-Layered Authorship

Korpfolksungen (1994; The Raven People’s Child) is the Finland-Swedish author and artist Irmelin Sandman Lilius’s (born 1936) fortieth book. She made her debut aged nineteen in 1955 with the collection of poems Trollsång (1955; Troll Song), and has since then established herself as one of Finland’s internationally best known writers of children’s books. Korpfolksungen unites several of the typical elements in Irmelin Sandman Lilius’s oeuvre: sliding between the real and the fantastical, between childhood and the world of the adult, between mythical time, historic time, and the present makes her a boundary-breaking, multi-layered writer for readers of all ages.

Among her first books are the four so-called “Muddle books”: Enhörningen (1962; The Unicorn), Silverhästskon (1964; The Silver Horse Shoe), Maharadjan av Schascha-scha-slé (1954; The Maharaja of Schascha-Scha-Slé), and Om härligas hus (1966; About the Blazing House), in which she lets her little daughter Muddle confront fantasy tale elements that eventually become part of her fantasy universe, the town of Tulavall.

Tulavall has traits of certain small Finland-Swedish coastal towns, Nykarleby and Borgå, where Irmelin’s mother’s parents lived, and not least of Hangö, where she lives with her husband, the artist and writer Carl-Gustaf Lilius. Tulavall was first visualised as the centre of events in the book Bonadea (1967; Bonadea)

“I started to write stories about a girl called Bonadea who lived in the town of Tulavall. Then it felt like I had come home. It was like building a place to live – one gathers all sorts of things from everywhere. At first Tulavall was a refuge, then it became a point of departure”, Irmelin Sandman Lilius has explained in an interview in the Helsinki daily Hufvudstadsbladet 12 August 1990.

The orphan Bonadea is the rebel of the small town. She lives free as the bird, outside the strictly hierarchical social barriers of the nineteenth century.

In the society that Irmelin Sandman Lilius builds in book after book there are authorities and rich citizens for a backdrop, but the protagonists are the poor of the back lanes. The Halter family in the trilogy about Mrs Sola – Gullkrona gränd (1969; Eng. tr. Gold Crown Lane), Gripanderska gården (1970; Gripander’s Farm, Eng. tr. The Goldmaker’s House), Gångande grå (1971; Eng. tr. Horses of the Night) – the Apelman family in Kapten Grunnstedt (1974; Captain Grunnstedt), Mattan från Kars (1989; The Mate from Kars), and Hästen hemma (1991; Home is the Horse); Hannafia’s family in Korpfolksungen – all live in an everyday reality marked by deep social divides.

“I think about the three of you sitting in the kitchen, and that it is probably a worn and grey kitchen, but every place is a good place to set out from. And time is a long road, a strange road that starts at the kitchen stairs and leads into the Future. I know how you imagine the Future. I have heard you speak of it from time to time […]. But imagine that you have taken the long road of Time and have reached the gate of the Future. You bang on it, and the Gate is opened and you step through, and there you stand and see that the Future is just another kitchen, terribly mistreated and the floor so wrecked that you get splinters in your fingers when you scrub it. And you would like at least to sit down for a bit to rest, but you haven’t the time, because you just have to hang in there and forget what the heart is full of.”

The lame woman’s letter to the daughters in Gångande grå (1971; Eng. tr. Horses of the Night)

The Work and Love of Women

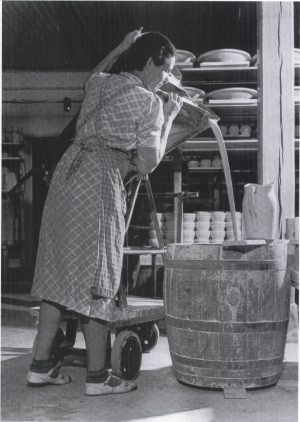

The world of the poor is to a large extent a minutely described women’s world, wherein the girls, even when very young, take on the tasks of women, take on adult responsibilities, and provide for themselves.

The point of view is usually that of the young girl. Her relationship with sisters, friends, the mother, and other older women is described with psychological clarity. The men of the books are brothers, fathers, potential lovers, and husbands demanding love, care, and attention. But it is not a case of narrating a woman’s martyrdom. On the contrary, there is a streak of warm sensuality throughout Irmelin Sandman Lilius’s books.

One of the strongest descriptions of young love is from the adult book Främlingsstjärnan (1980; Alien Star), about the artist Ellen Skärvmark and the poet Rudolf Aronius. The four “alien books” are also about artistic liberation and creation. Ellen Skärvmark’s character is what Irmelin Sandman Lilius has characterised as a “bow or a nod to three great Finland-Swedish painters: Helene Schjerfbeck, Ellen Thesleff, and Helena Westermarck”.

For Irmelin Sandman Lilius herself, pictorial creation apparently runs parallel to the verbal. She has illustrated most of her books herself.

Outside of Time and Space

Tulavall is not just a town of the late nineteenth century, but also the fairy world of the grey past where King Tulle created the realm Tuntula and married the lovely Libite, half human, half fox. Even in the realistic nineteenth century society, the fantasy queen rules in Mrs Sola. Bonadea, the truly ancient woman Fia, the sailor Tuspuru, and a part of Tulavall’s population of horses are the basis for the eternal fairy world.

Outside Tulavall, the sea swells and brings Valle Weathercap and his crew on the ship Southwest to real and fictitious places around the world.

Irmelin Sandman Lilius travels to and from Tulavall in time and space. Time for her is not chronological, nor is space static. In Mattan från Kars, Anna-Lina Apelman moves between the doings of home in Tulavall and adventures in the Caucasian Mountains. In Främlingsbilden (1990; Alien Image), Ellen Skärvmark and Rudolf Aronius step off a pavement in Paris at the turn of the twentieth century and into a lively and busy street in today’s Paris. In Korpfolksungen, the flying foundling Telit functions as a messenger between Tulavall and the ship Southwest. In Gripanderska garden, the alchymist Turiam is close to finding the philosopher’s stone and eternal truth.

“The old man called: Libite, Vidiranga, Hässa-Unn!

It rustled in between the screens of leaves, two hands appeared and a face, and then the entire girl. She looked like none of the customs people’s daughters, she was very small and dark. Her eyes were narrow and long, dark brown, and the nose was long, it almost made her look like a fox. Her hair reached to the knees, and her dress of thin leather hid her feet. When she came towards King Tulle he saw that she limped.”

Kung Tulle (1972; King Tulle)

Out of Tulavall and back again

In her later works, Irmelin Sandman Lilius far more often steps out of Tulavall’s fictitious world and into a more autobiographically determined reality. In exquisite little illustrated books like Observatoriet (1985; The Observatory), and Förvandlingstrappan (1987; The Changing Staircase), she returns to her childhood and youth, coloured by her time as a war-time refugee in Sweden, by the divorce of her parents, and by the tragic death of her stepmother. In 1996 she published her childhood biography Hand i hand (Hand in Hand) together with her sister, the writer Heddi Böckman.

The autobiographical part of the work lends new dimensions to Tulavall. Irmelin Sandman Lilius has time and again transferred her own harsh, exhausting childhood experiences of death, disappearances, and sisterhood to her fiction.

The unlimited fantasy and the presence of the supernatural was in her childhood primarily represented by her mother Tutu, Rut Forsblom, herself an author of children’s books. At the divorce, Tutu abandoned her children, just like the lame woman in the Mrs Sola trilogy. And just like the daughters of the lame woman, the Sandman daughters had to deal with their loss. They had to learn to live strengthened by having the best of what they lost still within themselves.

“Heddi and I stared at Tutu.

The thing about her was that usually she could make people do as she wanted them to. She wasn’t exactly beautiful, but she looked enchanting. She had brown wavy hair and grey-brown eyes, radiant eyes – it may have been the eyes that made people want to do as she asked them to. She had an amusing voice too, low and warm and a little hoarse occasionally. And she was swift and lively like a bird.

“‘Yes, she told the professor. You dwell in the always of the unlimited. But you don’t live. She looked at his empty coffee mug and asked: What do you give your watchmen to eat? What do they get to drink?’

“He replied: ‘Light. And dark.’”

Observatoriet (1985; The Observatory)

Translated by Marthe Seiden