Jette Drewsen’s (born 1943) work from the 1970s has become a symbol of the upheaval in literature, politics, and private life which the new women’s movement sparked. Her novels are about and speak to the newly conscious middle-class woman; they gave rise to discussions about the new form of women’s literature and its message – and over time they became reflections on a female aesthetic which is under constant change.

It was the Danish publishing house Gyldendal’s publication, in 1972, of Jette Drewsen’s debut novel Hvad tænkte egentlig Arendse (1972; What Arendse Thought) that launched women’s literature as a great publishing and readership success in Denmark.

Thus, the writer Liv in Pause (1976; Break) is preoccupied with writing a feminist article on the conditions for women writers, during the final days of a holiday in Malta. The text becomes both a description of the new, free, frustrated, and divorced woman’s life, and a reflection on the political and literary implications for the writer Liv – and for her author.

Liv is the third heroine in Jette Drewsen’s works and – as reflected in the symbolism of the name (Liv means ‘life’ in Danish) – the first who has learned to live in the new era. Ursula in Hvad tænkte egentlig Arendse (1972; What Arendse Thought) never escapes her suburban-housewife-humdrum-life, although she does manage provokingly to question Johannes Ewald’s Arendse and Kierkegaard’s Regine. In powerless jealousy, she also provokes her husband, who reacts with violence, and she is frustrated over her own lost creative ambitions. This debut piece mimics in form the two controlling mechanisms in the lives of the mother of young children: the division of daily life into parts and the circular repetition of the year. How could she possibly escape?

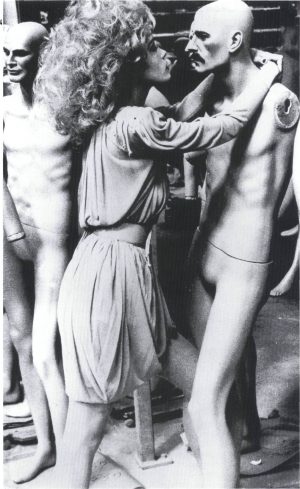

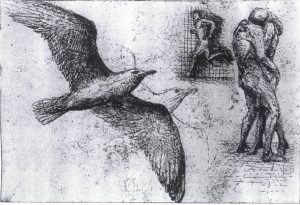

Mia is the divorced – and far from happy – main character in Fuglen (1974; The Bird). Mia, for “mine”, lives alone with her daughter Aline, has a loose relationship with a director, and has an opportunity, which is wasted, to create a mosaic for a bank. The mosaic depicts a bird, Aline’s bird, and thus becomes a symbol both of the desire to unite motherhood and career and of a dream of freedom, at least for the next generation. But whereas Ursula’s life was chopped to pieces, Mia’s completely disintegrates, and she takes her own life when her friend returns to his wife.

Jette Drewsen herself participated in the debate on Mia’s suicide and called attention to the division between social and psychological conditions as an important matter, especially for the artist: “[s]till, I don’t think one should avoid describing the social and psychological reality, which does not always fit the political theories put forth at any given time. The psychological structures, emotional attachments, do not always fall within the scope of the ideology. One of the objectives of art is to call attention to this fact.” From “Fiktion og kvindesag” (Fiction and Women’s Issues) in Dansk noter (1975; Danish Notes).

The two novels were more than reflections on the woman’s life and society of the day. They became, in themselves, subjects of debate, adding another line of thinking to the discussion of the female versus the male aesthetic and quality, of men’s ability to assess women’s literature, and of the objective of self-aware women’s literature.

Pause balances as a novel – and in its inscribed reflections on the novel – between detailed descriptions of a woman’s daily life, in which Liv puts on make-up, makes pizza, repairs a skirt, and sleeps with a Maltese lover, and the bigger theoretical and political demands on which Liv ponders in an article on women’s literature she is writing in the breaks between her other activities.

Pause becomes an ambiguous title that can be interpreted as the recreational function of the holiday break, but also as the reflective break that Liv inserts in between her practical tasks and which the author, Jette Drewsen, places in between her more dramatic narratives. On all levels the break becomes a breathing space that postpones and wards off disaster, making life (and Liv) possible. The reflection also includes a process of recollection, for instance of childhood holidays and of learning to avoid dangerous things – the ocean, venomous vipers – which also become part of the resources of adult life. Thus, the image of the break also takes on a dimension of depth that emphasises its life-giving function. Finally, the composition of Pause signals an acceptance of life’s many facets. Liv has slowly learned, as is emphasised time and again by the text, to be present in the tasks at hand without falling to pieces, without incessant suffering. In this way she also becomes a kind of lesson for a new woman’s identity, the socio-psychology of which Jette Drewsen draws to a conclusion in her last 1970s novel.

In Jette Drewsen’s novel Pause (1976; Break), the main character, Liv, reflects on a series of memories from her childhood in which she learned to sidestep life and death, such as at the Danish North Sea coast where the current and surf are stronger than people. She learns to cheat the ocean:

“We pretended that we were following the current along the coast, but always moved a little closer to land. In this way, we could reach the shore just as we wanted, but we had to accept that it would be somewhat south of our intended goal. That way the ocean had gotten its way, but didn’t actually win.”

Midtvejsfester (Halfway Parties) is about a dramatic turning point in the life of the journalist Nanna Jaeger, a looming dismissal, love troubles, and the attempted suicide of a girlfriend. However, the first-person narrative is written from a point in time after balance has been re-established, and the interest shifts from concern about her fate to reflections on the coherence in her 1970s life. And the divorced Nanna has found balance, with a network of family and friends so large that a party to which everyone is invited cannot fit in her flat.

The Woman and the World in Crisis

Whereas Jette Drewsen’s women through her 70s novels find a survival strategy, Anne Marie Ejrnæs (born 1946) starts her writing career with two novels about women whose lives fall apart over the gap between the ideals (of the 1970s) and the social reality. The crisis is a central, and by now not wholly negative, concept in her oeuvre, but for Karen in Karen og Sara (1979; Karen and Sara) and Stine in Når du strammer garnet (1981; When You Tighten the Net), crisis first and foremost means breakdown.

The stories about Karen and Stine can be read as despairing conclusions based on the university Marxism and the women’s movement of the 1970s. Karen arrives at a Danish upper secondary school with her anti-authoritarian teaching methods, her women’s consciousness, and her newly procured working-class literature, and suffers defeat by the system and the unwilling pupils. The school, which is presented on the book’s cover as an isolating, impenetrable wall, takes over Karen’s entire life, ultimately causing her to fall to pieces. Stine’s collapse, on the other hand, becomes a break. The story begins with her quitting her publishing job and ends with her living in a commune, a society outside society, where she meets Karen. It is a long process of resistance to established society and to the left wing’s cutting of the more complex connections in life. However, it is also an unreasonable story about an unreasonable woman whose resistance is that of the little child’s constant rebellion against the authority and power of mothers, against the mother’s and the grandmother constant suppression of the little girl.

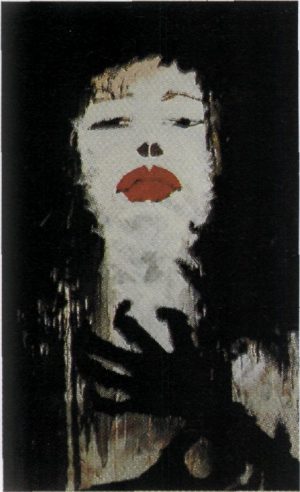

With Ravnen (1983; The Raven), the author moves towards horizons that represent something other than the traumatic left-wing contemporary Danish society, and the crisis takes on a new meaning. The novel is about the Danish academic Maria’s meeting with the African continent, whose darkness and many contradictions challenge every aspect of her identity as a woman. Africa is flowered dresses, oppression of women, rebellion, and a lover who is a phallocrat, a feminist, a Muslim, and a modern director of a publishing company. With a female metaphor, he offers to open Africa up to her, and she gives herself over to him and to the continent, to the ambiguous merging of love and politics, theory and life. Anne Marie Ejrnæs’s strategy is to allow her heroine to lose her head and yet remain intact in her meeting with the other, which in the end threatens to devour her in a violent stomach poisoning.

“You are my bird of ill omen, my black raven, the bird in the tall tree,” she tells her lover, who responds: “And you are the white death in me.” Black and white are present in them both: the little death in the sexual act points towards life in passion, in love, as well as to downfall. Thus, Maria finds femininity and passion on the dark continent, but she must take her own civilisation’s medicine to come back to life.

The body is a living player in all of Anne Marie Ejrnæs’s novels. It is active in sexuality and birth. The digestive system emaciates Maria in Ravnen (1983; The Raven), while colic torments Thomasine in Som svalen (1992; Like the Swallow) and Marie’s mother in Sneglehuset (1992; Snail Shell). The body matures and ages in a biological process that is intertwined with psychological and social history. It is not possible to ignore its sounds, smells, and appearance. The aesthetic principle in the work of Anne Marie Ejrnæs is the close connection between sensations and reflection, which is rooted in the human body. The female body becomes the carrier of history and change during pregnancy and birth.

Individual and Society

In Tid og sted (1978; Time and Place), Jette Drewsen presaged the collective narrative and interest in the historical. We move especially in the middle layer, where family norms are in upheaval as the women symbolically step out of the wash house (by the well) and into the labour market, the commune, political involvement, blurred personal relationships. A dialectic between time and space develops like that between the great events of the day and the individual’s actions and decisions.

Drewsen always approaches the grand narrative through the characters, through a psychological and moral interest in personal choices and opportunities. When, in her two 1980s novels Ingen erindring (1983; No Recollection) and Udsøgt behandling (1986; Choice Treatment), she tries her hand at the broad, socio-realistic story, she does so through montage-like cuts between the members of a large gallery of characters. The social sphere becomes a jigsaw and a network of people who are connected through love, business, family – and hate/violence. At the centre are two murders, one of which remains unsolved – for the police, but not for the reader or the central characters. The other sheds light on the correlation between power and morality in society, big and small. The 1980s novels expand the perspective from individual choice to social relations – and values.

With the trilogy about Ella, Lillegudsord (1992; Little God’s Words), Jubeljomfru (1993; Joyous Virgin), and Filihunkat (1994; Fililioness), Jette Drewsen explores the consequences of her constant reflections as an author on the meaning of artistic expression. Ella tells the story of her life from about age five to age nineteen, from a life at a Grundvigian gymnastics school, where her father is the headmaster, to life in Copenhagen as a new single mother and transcriber in the early 1960s. But she tells the story as a ‘we’ that only slowly becomes an ‘I’ in the name of normalisation. ‘We’ points towards a division and multiplication of identity – and towards the close connection between language and identity. The titles themselves contain linguistic complexity: they are all overly determined, pointing towards a generational story, a religious universe, a gender problematic – and towards the ambiguity of language. And from the outset, the language themes are brought together with the mystery of the sexes, the body, and religion which Ella meets as the highest meaning and the holy word. Ella consistently calls her father “the headmaster” and her mother “Illona”: they represent an institutional power and a private identity, and as such, she is unable to understand them as parents, in their job functions, or as individuals.

The novel’s linguistic awareness makes it extremely witty. The girl Ella hears the grown-ups’, especially her father’s, clichés and assimilates them into her own language. However, the playfulness is also an indication of imminent revolt: at upper secondary school, Ella cautiously asks her Latin teacher to explain how ‘I’ can be replaced by ‘we’ and she is given three answers: as pluralis majestatis, pluralis prudentis – and as madness. Ella’s ‘we’ is to be interpreted as a combination founded in a budding artistic identity that is established in the use of and revolt against the holy word, the Bible. She reads and interprets Brahms’ Ein deutsches Requiem for a friend whose boyfriend has died, and she quotes Saint Paul: Mulier in ecclesia taceat! (Let your women keep silence in the churches). But she does not hold her tongue. On the contrary, she perseveres and causes a scandal in the end when she modestly asks the headmaster’s permission to present a paraphrase of the great Danish pedagogue Grundtvig – for the school is built on the living word as well as the holy word – but instead, she majestically reads her own poem.

Ella’s revolt is turned towards the powerful father figure; symbolically and inexplicably, the mother is ill throughout the last part of the book and does not recover until Ella becomes pregnant. With the pregnancy, she has won back her body, which at the gymnastics school paradoxically splits off from the language in yet another mystery. For the child, language is taste and rhythm; in the adult world, the child has “sprung from someone’s loins”, its identity symbolic and abstract. With her little son, Ella has come into contact with reality, with the carnal, and with the opposite sex. She is no longer determined by her father’s eye, which has controlled her, his first and second wives, and the gymnastics girls at the school.

The theme of language is already apparent in the first pages of Lillegudsord (Little God’s Words), where the child Ella gets caught up in language as rhythm, in the mysteries of figurative language, symbolic speech, and the riddle of foreign languages that makes the line separating speech, sound, and letters even more blurred. “Dreams without disturbances are the best we know. We could, of course, wish for more reality, we would like some reality, with a vengeance. Flip-flops are real. We have flip-flops because the flip-flop shoemaker flip-flop had flip-flops, flip-flop, when we were in town with Illona to buy sandals. Flip-flop. We are very satisfied with our flip-flops.”

The Mirror of History

With Ravnen, Anne Marie Ejrnæs leaves behind contemporary Denmark. Kvindernes nat (1988; The Women’s Night) makes the longest journey back in time, to the year 1720, where the learned French marquise Gabrielle de Chambonin is held hostage in Africa, in Mequinez (Meknes), Morocco. Gabrielle’s meeting with the foreign culture contains parallels with Maria’s experiences. Gabrielle expects to find pure barbarism, but eventually learns to understand the rationality in a completely different social structure that is distinguished by, among other things, a technological progress that makes the hygienic standard much higher than in the Europe of the period. She finds analphabetism, cruelty, and oppression of women, but she also finds in the foul, old Empress Zidana a solidarity as an ambitious and power-seeking woman in a male-dominated society – and in suffering defeat in one’s ambitions. This frightening image of motherly power, the massive black body under a penetrating look of ice and fire, becomes a transformational experience. With her character, the work of Anne Marie Ejrnæs becomes reconciled with the most anxiety-causing images of the old woman’s power.

In the historical novels, movement is the central aspect, and old age and death is always waiting in the end. And in contrast to Karen and Stine, these novels do not search for the absolute. The abstract idea, which is the Achilles’ heel of the Danish left-wing in the early novels, fails in the face of reality – however, the idea only unfolds in the novel’s weaving together of politics, reflection, and life: “she had become involved on behalf of gender, abstract gender without a human face,” thinks Maria in a moment of self-criticism in Ravnen. And the moral is not to avoid involvement, commitment, and science, but to become involved in something concrete, for instance as the novels themselves merge the senses, the ideas, and the language of specific experiences together to form a whole that is always open and in movement.

Thomasine, nicknamed Sine, employs this same technique in Som svalen (1992; Like the Swallow), about Thomasine Gyllembourg who applies her husband, Peter Andreas Heiberg’s, concepts of freedom to their marriage and thus puts an end to their marital relations. She will only live with him in love, and the consciousness of being necessary as someone who gives and receives love becomes central to her life. Anne Marie Ejrnæs has her character fight for her Gyllembourg, take him, and then intervene in the lives of her son and daughter-in-law. Alongside this outwardly oriented activity she is tormented by stomach problems, colic, and constipation that only allow all that is locked in to come out in pain and putrefaction. Towards the end of the novel, Poul Martin Møller ultimately explains and defends the controlling mechanisms in Sine’s/Thomasine’s life: “If your sickness developed from a hidden desire to rule, then it was bad. I am more likely to believe it is a hypochondriacal fear in a vulnerable individual, a fear of losing one’s place in life. When one has that sickness, it is wise not to think too much over one’s relationships with others. One must live one’s proper life engrossed in one’s work.” The paradox is, however, that the woman for whom love was the most important thing must live through her work and find herself there. Anne Marie Ejrnæs views Thomasine Gyllembourg’s late oeuvre as an exercising of the masculine side of Thomasine’s life and name, but still as an activity that is controlled by her love and care for her son.

Seize the day(carpe diem) could be the motto for Sneglehuset (1992; Snail Shell), in which an unnamed ‘you’ in crisis relives her grandmother’s life, learns from it, and reconciles herself with her childhood memories of a disapproving elderly woman. Marie is another of Anne Marie Ejrnæs’s living and giving women whose life is again mirrored in the histories of her mother and mother-in-law. Whereas the mother, strained and bitter, holds back her body and emotions, and the mother-in-law after a hopeless love affair is forced into a marriage in which she defiantly goes mute, Marie chooses love and cannot stand to become hardened, even though the death of her little daughter threatens to cause her to stiffen. Her life is first and foremost her work. However, the love of life and the love for her husband and children are what give her the energy to work.

Marie also embodies an artist theme that comments on Anne Marie Ejrnæs’s own literary technique. The child Marie has a talent for drawing and uses her cousin, among others, as a model, first observing, and then later recalling and recreates what she saw. Perception is thus the first step in the artistic process. However, Marie dares to draw only a small part of her cousin, as she is afraid of impeding her growth if she draws and thereby retains her entire body on paper. Capturing the motion of life without halting or stunting it thus becomes the challenge of art: to sense, recall, and put down in images and words can be lethal for the object of the art. And Marie herself also becomes just an “object of fiction” until she reaches the age of the ‘you’; the rest of her life she lives her own life, happily and in respect.

In the historical novel Thomas Ripenseren (1996), which is set in the 1300s, Anne Marie Ejrnæs portrays her young, male main character in a complicated plot involving the church and the Begijns, holy women, in Flanders. The novel thus thematises a seminal historical confrontation between the influence of women and men in the life of church and faith, and makes the pure and tender sensuality of Thomas’ and Mathilde’s love affair a beautiful utopia.

Translated by Jenifer Lloyd