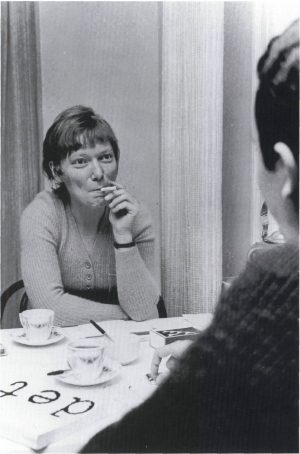

Inger Christensen (born 1935) made her debut in 1962 with the collection of poems Lys (Light), and even at that early stage in her career she touches on themes that continuously recur and unfold under varying points of view in her oeuvre.

With a few noteworthy exceptions, the most important and central aspect of Inger Christensen’s writing is her poetry. As early as 1955, while she was training as a teacher, she had her first poem published in the Danish literary journal Hvedekorn. An extensive familiarity with Nordic, European, even American poetry is already apparent in her first poetry collection, which has clear references to Nordic (including Södergran and Ekelöf), German (Rilke), and French (Rimbaud) modernism, while the style calls to mind American minimalism.

Her work demonstrates its own special view of modernity, while at the same time being representative of late Danish modernism. However, early Nordic modernism also had an influence on Lys and the subsequent collection, Græs (1963; Grass).

If I stand

alone in the snow

it becomes clear

that I am a clock

how would eternity

otherwise find its way

Lys (1962; Light)

The tone and scope show a kinship to, among others, Edith Södergran. As Södergran, Christensen’s collections revolve around an ‘I’ and a ‘you’, and around the position of the ‘I’ in a world of cosmic dimensions.

What is my dead cracked body?

Ants in snow have nothing to do.

No poem poem poem is my body.

I write this here: what is my body?

and the ants move me aimlessly,

gone, word after word, gone.

Lys (1962; Light)

Creation

Inger Christensen sees the word as a meeting place for the ‘you’ and the ‘I’, and for the ‘I’ and the cosmos. Her poems bring forth an ‘I’ as the landmark of the universe. And while it is first and foremost a lyrical ‘I’, the ‘I’ is also given a body and a gender in a reflection of its own femininity, as in the poem entitled “Jeg” (I), which ends:

Listen to the man’s whistling

Perceive the bird’s language

Calling I am a woman

I

I am the one who is open.

The poem can be interpreted as a commentary on Edith Södergran’s “Vierge moderne” (Modern Virgin), in which the woman is also “the one who is outside”, open and an observer. Openness and distance represent the prerequisites for the actual act of articulation. Even though openness is associated with the feminine, identity and gender are not the only things at play here. So is the relationship of the ‘I’ to the self, the body, and the other person – or, more generally: Otherness.

The recognition of light

in the word was accomplished

inconceivable act

from man to woman

Lys (1962; Light)

Absence and Presence

Whereas the movement in Lys is a visionary and airborne act of throwing the self out into the world, in Græs the movement is more cyclical. Inger Christensen opens Græs with the haiku-like poem “Fred” (Peace):

The pigeons grow in the field

From dust you shall rise again

“The limits of my language mean the limits of my world.” … “Everything we can describe at all could also be otherwise. There is no order of things a priori.”

Ludwig Wittgenstein, 1922: Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, sections 5.6 and 5.634

The organicist line of thought in the poem becomes a fundamental characteristic of her entire body of work. The cosmic space of the text communicates a presence that is associated with humanity’s inherent connection with nature. In contrast, the poetry collection’s final prose poems depict the relationship between the sexes as a nearness belonging to the claustrophobic triviality of the routines of marriage, giving it an anxious tone. This ambiguity includes not only presence, but also absence. Absence inflicts its alienation on the ‘I’, encapsulating it, as in the poem “Forstening” (Petrifaction):

On the table

lie my hands

Down on the floor

stand my feet

Out

far out someplace

I do not see

what you see

with my eyes

Absence threatens identity. However, it is juxtaposed with another type of absence as the prerequisite for the formation of identity. On the psychological level, it is about the separation that formulates an ‘I’ and a ‘you’, while on the existential level it is about the body, gender, and consciousness coming to life through separation from the state of nature as absolute presence in the self. The grass metaphor is the origin of the threads as well as the place where they ultimately meet again. The grass metaphor signifies the state of being inscribed within nature, from which humanity steps out and meets itself in the meeting with the other. The grass metaphor also draws clear parallels to grass growing on a grave, the ultimate in presence, the end of the self and of existence in the poetry collection’s fundamentally cosmic, cyclical vision.

Text as creation

Græs fades into prose poetry, and Inger Christensen’s two subsequent publications, Evighedsmaskinen (1964; The Perpetual Motion Machine) and Azorno (1967) are novels. Her work takes a new direction that not only concerns a change of genre, but also results in further emphasis on language as one of several themes in her poetry.

I see that I’m sitting and writing

See what is being written What was written

Read and see what has been read

See the silence again ahead

See it tune in to my writing

Vanish into what was written/what is writing

Read itself

Begin to shout to itself

det (1969; Eng. tr. it).

Azorno, in particular, animates the correlation between language and identity, even going so far as to influence the composition of the novel and the narrator issue. Whereas the language theme in the modernist poetry collections refers to the relationship between the ‘I’ and the surrounding world, the main concern in Azorno is showing how language is portrayed in the text and how language portrays the text and its characters. You could say that the text is its own main character.

Azorno is thus not a novel in the classic sense. It contains no characters with whom the reader can identify, and it sabotages the well-known plot structure of the novel. The book falls into two parts. The first consists of a series of letters written by five different women to each other, in which they each claim to be the one who belongs with the implied main character, Azorno. The second is a series of novel fragments with changing first-person narrators who partly coincide with the letter-writers from the first part. The problem here is that each new letter and each new fragment contradicts the previous. There is a constant and, throughout the text, never-ending relativisation of the reliability of the ‘I’.

While the reader is initially left mystified, when examined in more detail the text has a stringent structure with repetition as its basic rhetorical element. The many ordered, repeated passages serve as reference points in the novel’s labyrinthian flow. However, what is offered in this manner as a refuge turns out to lead nowhere in particular; it is in itself seductive, highlighting the seduction theme that is also suggested by the title (“Azorno” is a combination of the French “adorer” – meaning adoration – and the German “Zorn” – meaning passion).

Each character in the book is part of one large drama of seduction involving themselves and each other, a drama with fear as a recurring theme – fear of the fundamental uncertainty of identity and position. And this uncertainty is also conveyed to the reader because it is incorporated into the actual composition of the novel. Who writes what and to whom? Does the writer write the text, or does the text write the writer? These and similar questions cannot be answered. The only thing that is certain is that the language brings something forth in perpetual shifts.

Systemic Universes

1969 saw the publication of the major work of poetry, det (Eng. tr. it), which is often referred to as Inger Christensen’s breakthrough and as the most important work in Danish systemic literature. det seeks to depict a world from a neutral point, from the indefinable “it” – like the seed corn that brings the whole world into existence as it unfolds. This happens in the first part, “Prologos”, in which the isolated city dweller is ultimately born. The second part, “Logos”, expands on interhuman relations and relations between humans, nature, and language. “Logos” thematises the dominant ideas and movements

det’s third and final part, “Epilogos”, acts as a concretisation of all these themes as well as an existential expansion on them, highlighting the fear theme presented in the first poetry collections, and which in Azorno was turned inward with regard to the question of writing. In “Epilogos”, fear is a basic condition: “But it’s not a whole / It’s nowhere near finished / It’s not over / And it hasn’t started / It starts / In fear / In fear like a pause”, the almost proclamatory introduction to “Epilogos” says, and much of the alienation theme and criticism of power found in det results in a criticism of the notion of wanting to control fear rather than embracing it. Inger Christensen sets up three possible modes of conduct, all of which involve the subject’s letting go of its egocentricity and throwing itself out into the world: erotic experiments, magical experiments, and eccentric experiments.

det insists on the transcendence of barriers and on the possible, taking a stance that is understood and perceived as feminine later in her work. The theme is counterbalanced stylistically by the flowing rhythm of the language in the poetic interlacings in “Epilogos”, which are marked graphically as a heartbeat back and forth on the pages. Language as body, as organism, acts here as redemption for the three possible modes of conduct.

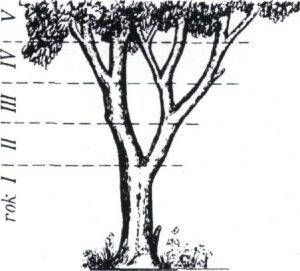

Inger Christensen has written three systemic works: det (1969), Brev i april (1979; Letters in April), and alfabet (1981; Eng. tr. alphabet) with structures inspired by mathematics, music, and linguistics.

Inger Christensen’s essay collection Del af labyrinten (1982; Part of the Labyrinth) can be viewed within the context of the discussion on the philosophy of language in the journals of the 60s and early 70s. Like her much later essays “Som øjet der ikke kan se sin egen nethinde” (1992; Like the Eye that Can’t See its Own Retina) and “Silken, rummet, sproget, hjertet” (1995; Silk, Room, Language, Heart), these early essays contain reflections on the relationship between poetry, system, and universe in an ever-expanding discussion of the issue that has been visible in her work from the beginning: the ‘I’ in a world of cosmic dimensions as a carrier of, and carried by, language.

apricot trees exist, apricot trees exist

bracken exists; and blackberries, blackberries;

bromine exists; and hydrogen, hydrogen

alfabet (1981; Eng. tr. alphabet)

These essays also comment on the status of the systems in the poetic works. The most stringently structured of her texts, det and the collection alfabet (1981; Eng. tr. alphabet), are made up of systems comprising two sub-systems. In det, the linguistic researcher Viggo Brøndal’s theory of prepositions as types of relation is connected with the number 8, while in alfabet there is a coupling of the alphabet with the exponentially increasing numbers of the medieval mathematician Leonardo Fibonacci (c. 1170-c.1250), the so-called Fibonacci sequence. The systems are also part of the actual meaning of the text. While det presents recurring stories of creation on the various levels of the text and with infinity as the perspective, alfabet is an apocalyptic vision. alfabet, too, depicts a world, placing an ‘I’ and a ’we’ within a culture and a cosmos; by virtue of the chosen system’s explosive growth, downfall is present from the very first texts of the work.

“No being, no state of being, no god can be preserved without dissolving again. No consciousness, perhaps not even humanity, without making a transition to other parts of the incomprehensible process which continues, not forward and not backward, but perhaps in a kind of heartbeat, similar to the spinning, osmotic story the universe tells itself in human consciousness.”

From “Terningens syvtal” (1977; The Seven of the Die) in Del af labyrinten (1982; Part of the Labyrinth)

The system brings to light a world, staging the labyrinths of language we are forced to move about in. The lyrical ‘I’ is therefore not a fixed and anchored entity. It is addressed, mentioned, paraphrased, and sometimes dismissed – or as Inger Christensen puts it: “derealised” – when one of the text’s other levels, for instance the cosmic, speaks.

This is a death that looks through its own eyes,

and will see itself in me, for I’m naive,

a native who is bonded to the stark

self-insight in what we call life.

And so I play the black-veined whitewing’s role,

fuse words with phenomena; I play

the fritillary caterpillar, gather

all the world’s life forms into one.

Sommerfugledalen (1991; Eng. tr. Butterfly Valley)

Transformational Mirror

Inger Christensen’s most recent poems, Sommerfugledalen (1991; Eng. tr. Butterfly Valley), reach back to the classical sonnet and comprise a sonnet redoublé, consisting of fourteen sonnets plus one master sonnet comprising the starting lines of the first fourteen. These are connected by means of the last line of each sonnet being the first line of the next. Thus, the structure in Sommerfugledalen is closed horizontally. However, by virtue of a changing kaleidoscope of points of view, lines have also been drawn across the individual sonnets, opening them to vertical readings and keeping the entire sonnet redoublé in constant movement.

Sommerfugledalen has the subtitle “A Requiem”, and death appears on several levels in the text. It is the ultimate boundary that sheds meaning, throwing it to the teeming life of the sonnets; however, it also appears as moments in the cosmic life processes within the text’s multitude of metamorphoses. These life processes deal with the transformative life of the butterfly, and the ‘I’ of the sonnets represents itself in a mirroring identification with the butterfly. The ‘I’ thus enters into the cosmic life and death processes, but also views them from the distance that consciousness (of death), reflection, recollection, and articulation create. In the mirroring recognition, the ‘I’ lifts itself into its own creation, seen from the point of view of death. The text itself highlights this movement as staging by characterising the efforts of the ‘I’ to bring “word and phenomenon” into correspondence as sport, as a poetic game.

In its aesthetic beauty and perfection, Sommerfugledalen is thus about both the passage of life and the nature of poetry, moving – like the decidedly systemic works – within an area that may be characterised as fiction, metafiction, or philosophy.

The problem of language in Inger Christensen’s writing is connected to the discussions introduced in the 1960s in the journal Nuancer (Nuances) and in the 1970s in the journal Exil (Exile). The debate was primarily geared towards the French philosophy of writing, semiology, and textual theory of the 60s, and both the editorial staff and contributors included text theoreticians as well as authors who produced systemic and theoretical texts, including Per Højholt, Klaus Høeck, and Henrik Bjelke.

Art and Existence

While Inger Christensen is primarily a poet, she has also written a number of prose texts, with her most significant work being the epic story Det malede værelse (1976; Eng. tr. The Painted Room), which expands on the theme of the systemic works: the relationship between people, language, and universe.

Det malede værelse borrowed its title from La Camera Dipinta, a room in the Ducal Palace in Mantua, which the painter Andrea Mantegna decorated in the late 1400s. It is an interpretive version of Mantegna’s Renaissance figures, woven into a modernist context. The work comprises three stories, each in their own genre: a series of diary entries with a male narrator, a fantastic story with a female narrator, and an essay narrated by a child. The three stories cross over into each other through, among other things, their mutual personal relationships. They supplement, relativise, and contradict each other’s statements in a complex network. The second story, with its jumps back and forth in chronology, most clearly illustrates the labyrinthian structure; however, the entire work can be viewed as a single labyrinth. The labyrinth becomes an overall metaphor, not just for the story but also for the perceptions of life that unfold within it.

Det malede værelse writes art on art and deals with the relationship of art to reality and power, as well as its importance for insight and existence. Through its multitude of registers, it reaches out into the mysterious in philosophical reflection on the fundamental questions of existence. It also contains a discussion of the powerful but frightened power-seeker who, in an effort not to lose his contours, decrees everything to be subject to his own order, and the stunting such a requirement of unambiguousness entails. In contrast, it holds up a utopia which it unfolds in three aspects, each belonging to its own story: the transcendent possibilities of art, the woman’s labyrinthian ambiguity, and the child’s openness to the multiplicity of possibilities.

Two years after the publication of Det malede værelse (1976; Eng. tr. The Painted Room), Inger Christensen succinctly writes in the baroque essay “Jeg tænker, altså er jeg en del af labyrinten” (I think, therefore I am part of the labyrinth): “The labyrinth as a kind of common frame of mind, a Möbius strip between people and the world – and in this type of labyrinth, it is actually only children who proceed at their ease: for they lift the enchantment by making it real.”

Throughout her work, Inger Christensen deals with the same fundamental conditions: the organic connections of existence, gender, the body, and consciousness with nature and the cosmos – and, by virtue of language, humanity’s special status in relation to this. Art is more than just the place where these conditions are referred to and described – as in early modernism. In the work of Inger Christensen, art is also the place where existence, gender, body, and consciousness can be put into play, explored, and tested, because they form the foundation of poetic articulation.

Part of the Liturgy of Burial in the Danish Lutheran Church

Translated by Jenifer Lloyd