Tove Ditlevsen (1917-1976) wrote poems from the age of ten; in 1937 she managed to get one of them published in Vild Hvede (Wild Wheat), a journal for young writers and artists. The title of the poem is “Til mit døde Barn” (To My Dead Child), the form is traditional, eight four-line stanzas with end-rhyme, but the content is striking: a mother talking to her dead baby boy as she lays him in the coffin.

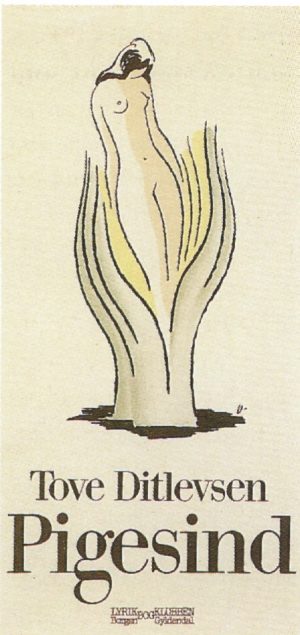

The poem was incorporated in the debut collection Pigesind (1939; A Girl’s Mind), which received excellent reviews. The readers viewed Tove Ditlevsen’s poems as beautiful and natural expressions of genuine femininity: no one seemed surprised that a nineteen-year-old publishing her first poem had chosen so morbid a subject as a stillborn baby – without apparently having any first-hand experience of either motherhood or death.

Til mit døde Barn (To My Dead Child)

I never heard your little voice.

Your pale lips never smiled at me.

And the kick of your tiny feet

Is something I will never see.

We have been together many days,

all my sustenance I shared with you.

You and I can surely not be blamed,

for all our weakness, yours and mine.

Infant child, you now will never feel

the heady pulse of life for good or bad. –

’Tis for the best, sleep soundly darling boy,

for we must yield to those of greater strength.

See how I kiss your icy hand,

happy to be with you yet awhile,

silently I kiss you, weeping not, –

though the tears are burning in my throat.

When the men bring in the casket white,

you need not fear, for mother will come with you,

I will dress you in your tiny silken shirt

for the first time – and the very last.

I will make believe you lived some days,

I will pretend that you have smiled at me,

and your little mouth has suckled at my breast,

so not a single drop remains.

How heavy is the footfall of the casket-bearers,

to no avail my laden breast awaits you.

Infant child, my golden now dead dream. –

Your tiny feet I kiss – and weep.

Even though the infant was stillborn, the poem starts out by describing a close symbiosis between mother and child, which is then crushed by a hard world and finally by the “heavy footfall” of the men who come to fetch the coffin. And thus the mother’s feelings also change. In the confrontation between the ‘weak’ world of the mother and child and the ‘strong’ world of the men, the child becomes objectified for the poetic speaker (the mother). This narrative voice is now that of an artist taking an outside view of the painterly qualities represented in the scene, or that of a little girl dressing up her doll, all the while talking to it in the sickly-sweet tone she hears in her imagination from her own idealised mother. The dead child – initially symbolising normal parental expectations – proves to function even better as corpse and baby doll. Had the child lived, he would have sucked his mother dry, whereas the dead child leaves the narrator in a state both of tension and release.

The poem can be read as an allegory of Tove Ditlevsen’s writing career, which was to produce one of the most significant bodies of works written by a woman in the Danish post-war period. Underneath the extremely simple surface, the poem anticipates recurring themes such as female identity, memory, and creativity. Loss of childhood and especially the symbiotic relationship to the mother are the foundation of Tove Ditlevsen’s melancholy poetics. Her writing is one long memory process, first as fiction, but gradually also in essays with an autobiographical reference point and in essayistic fragments of memory until publication of her autobiographical works proper, Barndom (1967; Childhood) and Ungdom (1967; Youth, Eng. tr. with Barndom as Early Spring, 1985), Gift (1971; double meaning: Poison/Married), Vilhelms værelse (1975; Vilhelm’s Room), and Tove Ditlevsen om sig selv (1975; Tove Ditlevsen about Herself).

Inner-City Childhood

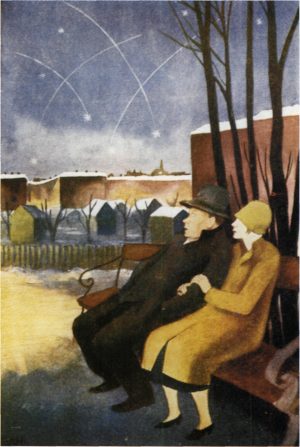

Even though “Til mit døde Barn” is more to do with poetry than with dead children, it has a link to actual death. One evening, in a dance restaurant, Tove had met a young man who had decided he would rather go to Spain to take part in the Civil War than stay unemployed in Copenhagen. He arouses both her sexual desire and her maternal feelings, and as she watches him walk down the street, knowing she will never see him again, some lines of the poem come to her. The finished poem has no obvious connection with him. “Still, I wouldn’t have written it if I hadn’t met him.” (Ungdom)

Dance restaurants, unemployment, and political commitment were crucial elements in Tove Ditlevsen’s childhood setting. She continually returned to the anxiety and shame inflicted by unemployment and poverty. “Inherited poverty always clings to an indefinable smell, which it is impossible to remove completely however much wealth and prestige one might later acquire.” (Parenteser, 1973; Parentheses). Tove spent her childhood in a small apartment with her mother, or in the backyard between privies and dustbins with the other girls from the street. Her teachers would have liked her to go on to upper secondary school, but her family could not afford it. Instead she went into service, which was meant to prepare her for the life her parents had planned for her: marriage with a “stable skilled worker who comes right home with his weekly paycheck and doesn’t drink.” (Barndom).

Tove Ditlevsen’s father worked as a stoker; he was class-conscious, read Gorky, and had a picture of Thorvald Stauning, leader of the Social Democrat party, on the wall. He made it a point of honour to provide for the family, so that his wife could devote herself to their two children and the home in the two-room apartment in Vesterbro, a working-class neighbourhood of Copenhagen. It was a catastrophe for the family when he lost his job during the financial crisis of 1924. For a time the unemployment benefit ran out, and he went on poor relief and lost the right to vote, the darkest moment of his life, Tove Ditlevsen wrote.

(Min nekrolog og andre skumle tanker, 1973; My Obituary and Other Sinister Thoughts).

The novel Barndommens Gade (1943; The Street of Childhood) gives a broad social-realistic picture of this Vesterbro milieu in the inter-war period. The account of a proletarian girl growing up is a female Danish counterpart to Martin Andersen Nexø’s account of early twentieth-century working-class life in Pelle Erobreren (1906-10; Eng. tr. Pelle the Conqueror). The poem “Barndommens Gade”, from the collection Lille Verden (1942; Small World), holds a concentrated description of the setting: “A few of us were standing on the pavement, / it was so boring in the flat, / and lanky boys came ambling by / they grinned and tipped their caps.” The street goes on to talk about its significance for the girl and the poet: “I am your childhood street, / I am the essence of you, / I am the pulsating rhythm / in all that you hope to do.” At the end, the speaker has been commissioned to write a poem that will motivate the farmers to invite the poor, little Copenhagen backyard kids into the countryside to be fattened up, but the process of memory leads to a sense of loss rather than one of regret: “The cobbled street of childhood / […] Tell me where did it go? / Have I betrayed it? / Is there no way back, / am I abandoned and rootless? / Nevermore to come home?”

“The street [Istedgade in Copenhagen] resembles a girl lying on her back with her head on Enghaveplads [an open square], young and innocent, with green trees, fountain, and Salvation Army meetings every Wednesday, with singing and confession of faith and strumming guitars. But by Gasværksvej [a road marking the beginning of Copenhagen’s red-light district] her legs spread and stretch long and carelessly down towards the railway station. Sprinkled over them like freckles lay the small, hospitable hotels, the cheerful shops with vegetables and bloody meat, a laundry with pale-faced ladies at their ironing boards behind the basement windows. Fat women stand arguing on the street corners, unemployed men hang about outside the cafés, cap on the back of the head and hands buried up to the elbows in their trouser pockets. Weary whores with no make-up on their grey faces disappear into the dairy carrying a cream jug, under the hard stare of the virtuous shop assistant.”

Barndommens Gade (1943; The Street of Childhood) and Flugten fra opvasken (1959; Escape from the Dishes)

The Mothers’ Bloody Inheritance

Despite the proletarian milieu, the theme in Barndommens Gade is more a question of gender than of class, and hope is more a question of personal (creative) liberation than of financial deliverance. The narrator shows solidarity in her account of a working-class childhood, but she nevertheless lets the central character judge the milieu from the perspective of middle-class values. This is especially true of the outspoken and brutal attitude to sexuality – which the narrator calls “unclean” – on the street and in the backyard. “Rough hands grope the body and bare it to the fleeing gaze.” When menstruation sets in, the “uncleanliness” enters the child’s world: “one morning, the mothers’ bloody inheritance comes with shame and harm to the untouched”.

Julius Bomholt, a leading Social Democrat politician and prominent cultural personality of the period, wrote a critical review in the party newspaper accusing Tove Ditlevsen of ingratitude to her background and of not having a political outlook because Barndommens Gade did not call attention either to wage work or to the labour movement as outlook on life.

“There is not a single little glint of love in the picture of the working-class home. Far from it. It is presented with coldness, as if Tove Ditlevsen consciously wants to renounce any sort of gratitude […]. The brother is a frequent patron of the municipal library at Jens Pedersen’s. If just a short chapter had been devoted to this aspect of the matter then the workers’ street – and the book – would have had a different perspective […] Getting away from the working-class environment has been described innumerable times since Hans Christian Andersen’s novel Kun en Spillemand [Only a Fiddler]. Every other short story in the glossy magazines is about the nice lady who works in an office and then becomes a Countess – or a clergyman’s wife. Well, that’s how it is.”

(Bomholt in Social–Demokraten, 20 September 1943)

In Tove Ditlevsen’s first novel, Man gjorde et Barn Fortræd (1941; A Child Was Harmed), the heroine has a sexual neurosis. She was the victim of a sexual assault when she was a child, but it is not until her engagement is broken off that she forces herself into an almost psychoanalytical memory process that reveals the offender’s identity; she can then pay him a therapeutic visit and be healed. Tove Ditlevsen’s heroines are more modest and innocent than the other girls on the street. Her home has affected her more strongly than the street outside: “The living room is an island of light and warmth for many thousands of evenings – the four of us are always there […]” (Barndom) Despite their poverty, the family had pretensions to maintain an intimate sphere that could float like a protected bubble above the dark shaft of the backyard and beyond the jurisdiction of the law of the jungle. Housewife Mrs Ditlevsen and her ‘woman’s mind’ gave life to this intimate sphere, while its existence depended on a good provider.

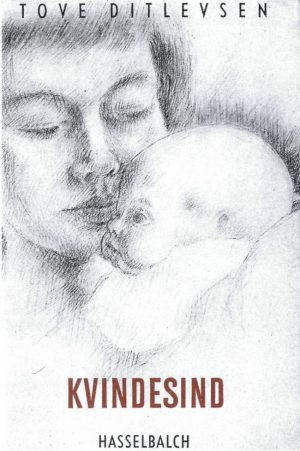

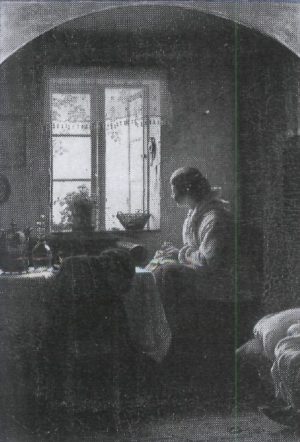

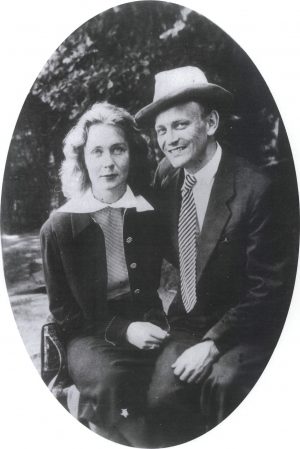

Tove Ditlevsen wrote the two novels about her childhood environment once she had left it. In 1940 she married the editor who had arranged for her literary debut; he was thirty years her senior. When he had left for his office, Tove would sit at home in his modern flat writing poems and novels; she had a more than nonchalant approach to housework and cooking. The older editor was soon replaced by academics of her own age: first an economics student, then a doctor who turned her into a drug addict, and from 1951 the successful civil servant and newspaper editor-in-chief Victor Andreasen, who weaned her off the drugs. She had a child with each of her last three husbands. Her marriages provided material for a number of novels and books of poetry. In For Barnets Skyld (1946; For the Sake of the Child), a divorce exposes the tangled relationship between child and parents. The woman’s initial joy was connected to the child’s ability to tie the man closer to the family: “It was as if this child had once, at a time of great need, come into being in her distended body when it was no longer able to keep hold of her beloved.” The divorce brings together mother and child in a close bond of reminiscence about the absent father: “The child [became] adult and the mother a child in their need for one another.” The daughter wants to keep them as a twosome, taking her father’s place; she causes a disaster when her mother gets engaged again.

Tove Ditlevsen’s view of marriage and the relationship between parents and children was, if anything, cynical rather than sentimental. In her collection of poems Blinkende Lygter (1947; Flickering Lanterns), the poem “Børnene” (The Children) plays out the entire parent phase in nine stanzas. Of the children we read: “First they were sweet expectation .[…] Then they were here, alive […] Suddenly they looked up / and left the childish games behind .[…] They straightened their young backs / and the house closed in on them […] But because they were good children / we often saw them later on; / two hours for Sunday coffee / they would sit and waste their time.” At this point, Tove Ditlevsen had a daughter, Helle (b. 1943), and a son, Michael (b. 1946), but the children have already entered the sphere of memoir. The collection also includes the poems “Syge Sind” (Disordered Minds) and “Depression”, presaging the conflicts faced by Tove Ditlevsen as a woman. “Syge Sind” is set in a psychiatric ward, where the women wait longingly for their husbands, even though they are the cause of their breakdowns. “Depression” is about the flipside of the dream of a happy life: when husband and children leave the housewife, the intimate sphere is transformed from an “island of light” into a “marshy mire” into which the first-person narrator sinks deeper and deeper “weighed down by your longing, weighed down by trepidation and sin, / you draw closer to the land of dead dreams”.

Tove Ditlevsen was hospitalised in connection with three of her divorces, and she always had a psychiatrist at hand. She had to undergo treatment to wean her off her addiction after her marriage with a doctor who had easy access to drugs and readily provided them in order to keep her with him.

The short story “Nattens dronning” (Queen of the Night), from the collection Paraplyen (1952; The Umbrella), on the other hand, casts a critical gaze on this female identity. Grete’s mother is going to carnival in a ‘queen of the night’ costume; Grete admires her white angel-hair wig, sequins, the eleven-metre tarlatan, and make-up, but her father, who is off to work a night shift, dismisses this Romantic self-representation as a manifestation of vulgar illusions promoted by the entertainment industry. He wants his daughter to read fairy-tales collected by the brothers Grimm rather than stories in magazines, and when Grete looks into his eyes she, too, sees a dropped sequin as “just a piece of dented metal”. In two subsequent ‘marriage novels’, Vi har kun hinanden (1954; We Only Have One Another) and To som elsker hinanden (1960; Two Who Love Each Other), both of which were commissioned works for Danmarks Radio (Danish Broadcasting Corporation), the disillusion becomes increasingly intense. No matter how much in love the man might be at first, coupleness seems to smother his feelings.

With her experience of broken marriages and their illusory happiness for women, Tove Ditlevsen moved in several directions. The one led her to what would later be the social-political stance of the new women’s movement. “Piger uden cellofan” (GirlsWithout Cellophane), from the essay collection Flugten fra opvasken (1959; Escape from the Dishes), attacks the artificial image of women promoted by advertising and glossy magazines.

The perspective in Tove Ditlevsen’s essay resembles that of a classic feminist text: Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique (1963).

“Every healthy woman who is past puberty ought to feel degraded on behalf of her entire gender by this mindless hype that prostitutes everything it makes the weaker souls believe it will uphold: the lovely, natural relationship between man and woman.” Tove Ditlevsen was calling for a women’s revolt more than ten years before it actually happened: “It must therefore be time to rise against this upsurge in specific targeting of the woman’s vanity.” In “Stakkels frigjorte kvinde” (Poor Liberated Woman) she makes it clear that freedom and free time go hand in hand, and that being “liberated” simply means that ordinary women suffer even more unless the authorities step in and take on some responsibility for the children. Opinions such as these formed the basis of her extensive journalism and her long-standing assignment as ‘agony aunt’ for the weekly magazine Familie Journalen.

Tove Ditlevsen considered herself primarily a lyric poet, but she wrote in all genres, including two children’s books Annelise – tretten år (1958; Annelise – Aged Thirteen) and Hvad nu, Annelise (1960; What Now, Annelise).

The Witch in the House

Tove Ditlevsen’s creative writing took her in a different direction, however, towards insight via psychology and language into the very core of her femininity. The collection Den hemmelige rude (1961; The Secret Window) ends with six poems which, on the pretext of interpreting the fairy-tales of the brothers Grimm, allow the first-person voice to assume the stance of egoistic and cruel mother. In “Askepot” (Cinderella) the wicked stepmother is punished, but wickedness lives on in the innocent child: “But deep within the child’s heart / a nascent seed does lie. / Planted by the wicked stepmother / it can never die.” In “Forældrene” (The Parents) the children are deliberately sent off to the witch and the gingerbread house so that they do not tax the resources of the home: “We own […] [e]nough for ourselves, but not enough for you too.” The last poem in the collection, “Heksen” (The Witch), signals the discursive starting point for Tove Ditlevsen’s late works: “Do not enter the house./ Here a witch has her home.” The home is gilded, but anyone who enters will be devoured by the witch’s dragon. “Do not enter the house,/ although the sight might dazzle thee,/ for the dragon is my heart,/ and the witch resembles me.”

On Den hemmelige rude:

“The best poems in it are six to seven with motifs taken from the Grimm brothers’ fairy-tales. Through an antiquarian bookseller, I had got hold of the same rare edition of them that I had owned as a child, and while I read them aloud to my son, I made sense of them for myself […] At the same time I began to take a less sentimental view of the parents/child relationship.”

Tove Ditlevsen om sig selv (1975; Tove Ditlevsen about Herself)

The home was the woman’s, the mother’s domain, but she might turn out to be a witch. Tove Ditlevsen only ventured to tackle this truth at a late stage in her career. In the memoirs we can trace her step-by-step approach to a realisation that femininity and motherhood are not exclusively the province of goodness, but are equally a chaos of all the unpredictable and perilous instincts she long hoped only existed in the fairy-tale picture books.

“[…] my book [Man gjorde et Barn Fortræd] has come back from Gyldendal publisher with a strange response that claims I have read too much Freud. I don’t even know who Freud is.” (Gift)

The novel was eventually accepted by the new publishing house Athenæum.

Tove Ditlevsen’s first four fragments of memoir are found in Flugten fra opvasken; of these, “Min gade” (My Street) opens with a direct quote from Barndommens Gade. Her fiction was close to her personal experience – or vice versa. She declared that “unless it’s fairy-tale or poetry, it is impossible to write about anything you have not in one way or another experienced first-hand.” (Tove Ditlevsen om sig selv). She also observed that an emotion is only really experienced the first time: “Only one love is granted, and it comes to us in childhood like a blazing sunrise, like an earthquake and a shock wave – and later it is just a memory and the will to experience anew.” (Barndommens Gade). The unique experience can be repeated, however, in continually re-invented language; this reiteration is simply memory.

Seven years after publication of her memoirs, Tove Ditlevsen wrote a short autobiography with inserted excerpts from her literary texts. Here we are left in absolutely no doubt that her relationship to her mother was the determining factor in her life:

“I loved my mother in a primitive and spontaneous way, and the large shadow over my childhood – far bigger than the material insecurity – was my always gnawing doubt as to whether she returned my love.”

Tove Ditlevsen om sig selv (1975; Tove Ditlevsen about Herself)

The poem “Erindring” (Memory) from Den hemmelige rude tells about a Sunday outing to Søndermarken park, where her parents were happy: “My mother and father were happy. All along the street / they walked like cheerful children, in their own little world.” Her father’s walking stick smacks the flagstones, her young and elegantly dressed mother opens the gate for the children, and together they eat lunch in the open air. Even though the rest of her childhood was grey and sad, this happy day lives on in the child’s memory as hope and solace. “And only in memory does the heart find peace. / My mother was young. I had never noticed that before. / My father was happy. And happiness dwells somewhere / behind Søndermarken’s green slatted gate.” Tove Ditlevsen does not remember her parents’ love of little Tove, but, on the contrary, their love of one another (“in their own little world”); on this day they were a picture of love itself, a picture she is later able to put into words. As she finds a way to articulate the happiness her parents exuded, so too does her heart finds peace. The real-life happiness disappeared, but Tove Ditlevsen often pointed up that she did not care for reality. Her poetics was a language with which to restore lost reality.

Poetics of Melancholy

Barndom opens with a chapter that goes further back than the earlier fragments of memoir, back to the point where Tove’s poetic language is born. The scene is the apartment; mother and five-year-old Tove are still at the breakfast table after father has gone to work and brother to school. “So my mother was alone, even though I was there, and if I was absolutely still and didn’t say a word, the remote calm in her inscrutable heart would last until the morning had grown old and she had to go out to do the shopping in Istedgade street like ordinary housewives.” The mother’s moods are the child’s emotional horizon. The youngster begins the day with an open mind and hope centred on the mother who, if she wants, can fill the whole world with love. The first sentence of the chapter reads: “In the morning there was hope.”

When Tove was six years old, Mrs Ditlevsen had a stillborn baby delivered by Caesarian section. “They told me that mother had a bad tummy, but Edvin [Tove’s brother] just laughed and later explained to me that mother had ‘amborted’. There had been a baby in her tummy, and it had died in there.” (Barndom). Tove Ditlevsen never linked this experience to her debut poem, perhaps because identification with her mother was so long repressed.

Beyond this female universe there is a backyard and a street. Looking down at the backyard, the little girl sees a green gypsy wagon and its two grotesque occupants, Scabie Hans and Pretty Lili; the neighbours’ presence is felt in noise from the stairwell. As long as she has hope that her mother loves her, then the child is protected against the brutal outside world. This protection, meanwhile, obliterates the child as individual; the mother is alone, even though her daughter is there. The child is absorbed in the mother; their female world is a forum of stillness and identity, full of love and beauty: “[…] strange and happy mornings when I would leave her completely in peace. Beautiful, untouchable, lonely, and full of secret thoughts I would never know.” Young Tove feels that her mother’s secret thoughts both include her and lock her out. So long as she reflects her mother, they are united in a shared consciousness. Tove sees the sun break in reflection on the gypsy wagon, as if it came from inside the wagon; Scabie Hans stands bare-chested, washing himself; Pretty Lili hands him a towel. Tove registers their movements as fluid and colouristic visual impressions. As long as love fills her world, these pitiful characters would remain “colored pictures in a book”. Protected by a feeling of belonging to her mother, the child’s world is devoid of anxiety. But nor is it real. Only the apartment and her mother are real; a film is rolling outside the window, showing scenes from another sad, but remote and therefore beautiful, life.

When the child draws attention to herself, the world becomes “cold and dangerous”. Tove has turned her eyes away from her mother and towards a picture hanging on the wall – of a seaman’s wife sitting in a cosy room, waiting for her husband to come home from sea. Her infant child sleeps snugly in a cradle behind her. To Tove the seaman’s wife is the image of the ideal mother whom Tove loves, a remote and beautiful dream. At the sight of her daughter’s naive belief in the picture’s touching facade, the mother explodes in un-maternal sexuality and egoism, forming a counter-image to the sentimental picture on the wall. “She shoved the chair aside, got up and stood in front of the picture in her wrinkled nightgown, her hands on her hips.” Then she sings a song about a similar situation: the mother sitting at the window, the infant in the cradle, but here the wife is not waiting for the father of the child, he has already come home; her desire is focussed on her lover, waiting outside.

The rupture between mother and daughter is marked by the sentence: “When hope had been crushed like that” – and the mother reacts with anger, irritation, and rejection. She becomes “foreign and strange”, the child is frustrated and no longer has any sense of shared identity with her mother. While they clear the table and get dressed, they are disturbed by the disorder of brutality and wickedness that obtains outside their female world. The mother looks at the child with “cold hostility”; Scabie Hans and Pretty Lili start to fight; the hatred spreads and activates all the latent violence in the setting; the mother slaps Tove for no reason, then puts on her wife’s mask, ready to go out, stern face and reddened cheeks. Tove’s world has been split into wicked and good; the good and loving mother hangs on the wall, while the real-life mother is wicked and cruel, a stepmother: “[…] I thought that I had been exchanged at birth and she wasn’t my mother at all.” And in her dilemma, Tove’s poetry is born: “[…] inside of me long, mysterious words began to crawl across my soul like a protective membrane. A song, a poem, something soothing and rhythmic and immensely pensive, but never distressing or sad, as I knew the rest of my day would be distressing and sad. When these light waves of words streamed through me, I knew that my mother couldn’t do anything else to me because she had stopped being important to me.”

For a long time, Danish literary scholarship had an ambiguous attitude to Tove Ditlevsen’s writing because of the perspective in her early works. Jette Lundbo Levy writes in De knuste spejle (1976; The Broken Mirrors):

“[…] I remember how, when I was fifteen or sixteen years old, I fled, in a figurative sense, as fast as I could from having anything more to do with that writer; I did not want to see myself in the restrictive female role or cultivate the kind of sensibility that I thought her writing represented.”

Having experienced her mother as absolute goodness or absolute wickedness, Tove Ditlevsen took on these positions by turns in her writing process, or she assumed the opposite position as the poor little ill-treated and wounded child. Her urge to write initially stemmed from a desire to recreate the good mother and protect herself from the wicked one. In “Til mit døde Barn”, however, it is the good mother speaking, and the vantage point in Man gjorde et Barn Fortræd is that of the wicked mother’s victim, the poor little child. It was this perspective and its expressive tone that caused some reviewers to look upon Tove Ditlevsen’s work with a degree of forbearance. Her vantage point seemed locked in positions reminiscent of stereotypical women’s roles: the passive, idealised madonna or the masochistic, self-pitying wretch. The point of view could, however, also be transferred to the wicked mother, the witch. At an early stage of her career, in Pigesind, the first-person voice in the poem “Erkendelse” (Acknowledgement) acknowledges her sadism. She picks up a vase, the prized possession in the home, and drops it – on purpose. “Now the world is mean and joyless. / Ten thousand shards never to be joined again.” By admitting to destructivity against the mother (the vase), the first-person acknowledges that she, too, bears the dreaded (maternal) wickedness. For many years, Tove Ditlevsen had a compulsive attachment to this fascination with the mother; a fascination which made her objectify herself in relation to her and to the subsequent mother-substitutes, her later love affairs, and particularly her last (unpredictable) husband. It was not until she started writing her memoirs, however, that she was able to free herself and break out of the compensatory language. The background to this was the personal crisis into which she was plunged after her final divorce. She had a nervous breakdown, attempted suicide, and was admitted to a psychiatric hospital, where she stayed for a lengthy period during which she wrote her two first volumes of memoir and the ‘psychosis novel’ Ansigterne (1968; Eng. tr. The Faces). The traumatic binding to mother/love-object now became the theme in her writing. Tove Ditlevsen reconciled herself to the loss of the good mother by facing up to the fact that her mother was a sum of good and bad sides, and by recognising her own similarly complex nature.

The earliest versions of Tove Ditlevsen’s memoirs were published in the weekly magazines Nyt Femina in 1966 and Søndags–B. T. in 1971. They caused a tremendous stir, because she wrote candidly about many well-known names. She was, however, most forthcoming about her own actions. Among other episodes, she wrote a detailed account of her difficulty in arranging for an abortion when she became pregnant very soon after giving birth to her first child. Abortion was still illegal in 1966, but it was the subject of intense public debate, and her admission about her own ordeal in the 1940s substantiated demands being made by the women’s movement for changes in the law. Her visit to one doctor proceeded thus:

“Just take your underpants off, so I can examine you to find out if you are pregnant at all. Full of hope I got onto the familiar examination couch and lay down. He unbuttoned his trousers and, with no resistance on my part, availed himself of my convenient position – I had never looked upon my private parts as if they were the crown jewels. It could not be called a medical examination. I got off the couch feeling jubilant, convinced that my troubles were now over.”

(Nyt Femina, 1966) This passage was not included in book form.

The theme in Ansigterne is the conflict between motherliness and sexuality. The novel is about Lise Mundus, an author, who is hospitalised with severe hallucinations following an attempt to take her own life. She had felt driven to suicide by two people: firstly her husband, who has a preference for younger women, one of them being her daughter from a previous marriage; secondly their housekeeper, who is part of the youth rebellion and demands political activism, collectivised emotional life, and creative modernism. On the plot level, this menacing world is miraculously pacified when Lise’s husband fires the housekeeper and promises renewed fidelity. Psychosis, which is the real theme of the novel, is overcome more covertly in Lise’s inward struggle with her ideals and sexuality. In two central scenes, Lise sees through the illusion of her own ideal motherliness – and, by relinquishing it, she becomes sexually liberated. In the first scene, Lise confides in the doctor about her husband’s borderline incestuous attempts at her daughter; she abandons maternal defence of her daughter and instead identifies with this daughter’s love for the (step-)father, which triggers an orgasm. In the second scene, Lise is confronted with the threat of losing her own face while her younger son would get to keep his, but she chooses in favour of herself. “‘No,’ she said absently. ‘I need my face more than he needs his.’ […] Lise slipped away on a wave of joy and fear and pain […].”

The consultant psychiatrist focuses his treatment on trying to get Lise writing again. The first text she writes is a snippet of memoir from her eighth birthday, when her parents gave her a doll she did not like. “The hideous pink doll stared at me with its dead glass eyes […] Someday, I decided, I would have a real, living child, and it would not have any father. I didn’t want to ever get married.” The “living child” Lise wants is the (doll)child’s death and resurrection as poem – the very transformation addressed in Tove Ditlevsen’s debut poem. This transformation involves the death of illusory motherliness and the resurrection of femininity as language; liberation from procreation of children and gender roles to the desire of body and language. The “living child” is the femininity that Tove Ditlevsen could take over from her mother while simultaneously relinquishing that mother for ever. Tove Ditlevsen signalled the taking over of this (at that point, deceased) mother’s femininity by giving her mother’s maiden name to the central character: Mundus.

Working through her relationship to her mother and then her own motherliness ended in inner strength, but also in absence of illusion, which in Vilhelms værelse, when it came to her husband of more than twenty years, turned destructive. In Vilhelms værelse Tove Ditlevsen (from the memoirs) writes about Lise Mundus (from Ansigterne), a woman whose husband has left her. Memoir and fiction, narrator and central character, chronology and locality are mixed together in a dynamic sketch of the story of the couple, written in a baroquely humorous style, which nonetheless often threatens to turn into morbid despair. All meaning has now deserted previously important spheres of life; the narrator/Lise cannot love her children once they have grown into adults; sexuality is only kept alive via perversion; even the hitherto sacred sphere in Tove Ditlevsen’s texts – language – is prostituted because Lise’s literary success becomes a point of competition between husband and wife, and because Lise surrenders their divorce to the entertainment media. The wreckage of the marriage is metaphorically represented by the narrator writing the book while workmen are demolishing the couple’s former apartment, and the process ends with Lise’s suicide.

Once the autobiographical material had been exhausted and all the key characters in her childhood universe – her mother, father, and brother – were dead and her husband had left her, Tove Ditlevsen ended her life as she had presaged. In a late poem (from Det runde værelse, 1973; The Round Room) she compares herself to her ageing cat:

No more birds to hunt

no mice to scare.

No escape from the labyrinth

of memory.

Gently life runs out

like drops along a drainpipe.

Translated by Gaye Kynoch