The struggle for Norwegian independence along with a growing national consciousness culminated in 1905, when Norway broke away from union with Sweden. Norwegian society was undergoing major changes. Industrialisation had taken off, and traditional ways of life in the rural areas were in a process of disintegration. The Norwegian writer Ragnhild Jølsen (1875-1908) felt these changes at first hand. When she was very young, she came into contact with leading circles in Norwegian literature and the visual arts, and she received tuition in sculpture and modelling. At the same time, however, her family and the family estate played a central role in her life and writing. Her family had lost their estate and thereafter lived a simple life, first in Christiania, later in her home village of Enebakk. Ragnhild Jølsen’s life and writing is marked by the tension between her rural home village and the bohemian milieu in the capital city, between robust popular traditions and aesthetic sophistication. Rikka Gan (1904) and Hollases krønike (1906; The Chronicles of Hollas) are the two major works in her brief writing career. The novel is dominated by a dark, pessimistic tone, while the chronicle is full of folksy humour and vitality.

Rikka Gan has two central characters: a woman and an estate. Rikka is an uncommonly sensitive and passionate person – with an artist’s nature. She lives with her impoverished family on the run-down estate Gan, which her family has had to give up. Despite her sense of pride, she lives a life in degradation. She has taken Gan’s new owner, a ruthless and wealthy man, into her bed so that her family can stay on what was once the family farm. In this way the estate and the woman’s crises are linked together. Gan represents a mysterious and ominous universe:

“Black lay Gan farmhouse with its sleepy echo, and the tree roots shivered down in the garden. The sun came sparkling in summertime […] It was not able to sparkle in anything at Gan […] But when darkness came seeping up from the water and out of the forest […] that was when Gan farmhouse awoke and grew.”

A woman screaming in the storm, roots winding hither and thither, a gloomy estate where misdeeds have been committed – all elements from the genre of romantic horror, from the Gothic novel, which Ragnhild Jølsen revitalises with a bold pen. A refrain-laden, lyrical language, tensely condensed scenes, dreamlike images of nature, and a complex, sensual perception of humankind merge together in her universe. Ragnhild Jølsen created a national, literary Jugendstil, in line with the artist Gerhard Munthe’s furniture design, paintings, and book illustrations, and textile artist Frida Hansen’s woven tapestries.

The Meandering Line

Jugendstil was a trendsetting style in Europe around 1900. Like symbolism and neo-romanticism, it is based on an idealistic view of art: through art it is possible to formulate an all-encompassing project for life, often with utopian features; it is possible to create another reality. The aesthetic programme for Jugend put beauty at the top of the agenda and was enthusiastic about exclusivity and uniqueness. The lifestyle or world picture expressed by Jugendstil can be read as a protest against the mechanisation and industrialisation of society. But it can also be seen as flight from a menacing reality and surrounding world. The intentionally stylised and ornamental forms are a new and key feature. The motifs convey a fairytale and dreamlike atmosphere, and touch on issues which at the time were taboo. The distinguishing feature of Jugendstil was the meandering line, which could be turned into flower garlands, women’s flowing hair, dragons, and other fabulous animals. Literary oeuvres with these leanings can be found throughout the Nordic region.

Inspiration for the Jugendstil came from the Danish writer J. P. Jacobsen; Selma Lagerlöf was a prominent name in Sweden, and Thomas Krag was an earlier exponent of the style than Ragnhild Jølsen in Norway. Its particular significance was in the figurative language used to describe nature and in the portrayal of women.

Ragnhild Jølsen was hypersensitive to the atmosphere itself in the new literature, and she received positive response from reviewers. From her very first publication in 1903, she was welcomed as remarkably mature, unusually gifted, and singular. But her “brutal, raw power” and “blatant, intensely erotic scenes” led many to believe that the author must be a man. Would a lady be able to write like that at all? In 1907 the influential Norwegian critic Carl Nærup highlighted her ability to draw characters and her stylised, lyrical, musical language. He praised her fertile “novelist imagination” and “bold and singular talent”. Her contemporaries regarded her as a writer of ‘regional’ literature, because she described forest nature and old farms. As she gradually used more and more dialect and a more purely Norwegian language, she was praised for being ‘national’ – also an effect of the ‘1905 syndrome’. Today, it is easy to see just how ‘modern’ and European her talent was. She derived inspiration from various art forms and integrated them in the Gesamtkunstwerk that the Jugendstil wanted to create. Her entire world is in harmony with the Jugend concept of beauty and the interest in taboo and ambivalent spheres. In the annals of Norwegian literature, Knut Hamsun and Sigbjørn Obstfelder have won a prescriptive right to be the innovators of the period, but Ragnhild Jølsen deserves a prominent place alongside them as ingenious innovator in genre and language.

After Ragnhild Jølsen’s death in 1908, Sigrid Undset and an older writer friend Nils Collett Vogt spoke about her “and were in agreement that she was a genius”, writes Tordis Ørjasæter in her biography of Sigrid Undset, Menneskenes hjerter (1993; Human Hearts).

When working on her first published novel, Ve’s mor (1903; Ve’s Mother), Ragnhild Jølsen was given advice by the writer Hans E. Kinck. Her rhythmic language and her realistic – in part grotesque – characterisations recall Kinck’s style. But it is the work of Selma Lagerlöf with which her writing has most in common. Parts of Gösta Berlings saga (1891; Eng. tr. The Story of Gösta Berling) have clearly provided inspiration for Hollases krønike. Both writers work with a personal blend of realistic and Romantic levels of text. Ragnhild Jølsen alternates high-flown invocation and lyrical elements with use of dialect and colloquial language. The dialogue varies between, on the one hand, archaic forms and rhetoric in elevated style and, on the other hand, racy, local proverbs and curses.

Sensitivity and Sensuality, Self-love and Self-hatred

Ragnhild Jølsen’s books are concerned with a type of woman who is beautiful, vulnerable, and sensual, and whose mind vacillates between dream and reality. The characterisation underscores aggressiveness and ambiguity. Rikka Gan’s anxiety and self-hatred, deep depression and self-centredness are on show throughout the novel. Something similar is the case for Rikka’s niece in the sequel, Fernanda Mona (1905), and in Hollases krønike, even though these characters’ self-images are weaker. The heroines’ personalities exhibit distinct narcissistic traits. They live off their self-love, but also off self-hatred. They are possessed by unrealistic fantasies of grandeur, but at the same time lack the ability to function when not being loved and admired by others. On the one hand, love affairs substantiate their self-images; on the other hand, losses in love lead them into depression and emptiness.

An example of the way in which playfulness, laughter, and grotesque images are active narrative energy in Fernanda Mona can be seen in the double portrait of the Gan girls. The twins are juxtaposed with their elegiac sister Fernanda Mona. The two girls are more akin to women from the folktale and saga tradition – just like their aunt Rikka Gan:

“And then the two lynxes stormed around the table, as frenzied as maenads, kicking and hurling, their short, scruffy hair flurrying around them […].”

The girls drink themselves into a stupor on their father’s funeral beer, bait the bullocks, seduce their own cousin, try to do away with Gan’s wealthy owner – but end up allowing him to entertain them. The description of the three sisters illustrates the scope of the writer’s picture of women. The narrative pen takes a critical approach to both these extremities, but great creative zest has been imbued into the portrait of the fiendish twin girls.

Ragnhild Jølsen’s women do not reach a stage of compassionate maturation or adult independence. Patriarchal family structures and the mothers’ powerful upbringing inhibit and impede them. Their rage, anxiety, and feeling of loneliness resemble that of the child. Dream is for them a creative resource – their artist’s gift, through which they struggle to find a sense of self and identity. Rikka drowns when she abandons herself to her own dream, that of Vilde Vaa, who only exists in her forest fantasy: “taken into the dream of her youth, she reached out her arms: Vilde Vaa, Vilde Vaa.” She dies in the encounter with her dream lover, who is in reality an aspect of herself.

There is, however, something of value in the intensity and self-love which has special significance for women’s development of self-confidence and independence. The heroines’ egoism and self-assertion does not vanish, but it is reshaped when they endeavour to fill out their ideals and conceptions of themselves. They attempt to ‘overstep’ themselves by means of creative activity. Paula does it by playing with her son (Ve’s mor), Rikka in fantasies and visions, Fernanda Mona with her love of flowers and the garden, Angelica in Hollases krønike in the intoxication of creation when she is painting. They are all filled with the dream of beauty and longing for the virile and tender lover.

Rikka and Fernanda Mona are only able to maintain their self-images by dying. Loss of love also makes Angelica destructive – she destroys her great painting because it reveals knowledge of herself that she cannot accept. But she, too, has a vision for the future as regards women and love. Her prayer to God, that longing be replaced with action, can be interpreted as expressing new insight and new artistic work – as writer: “Teach me to cry out my want, so that my voice will finally be heard, reach all slavish souls, help them out of their inherited thralldom, that they might already in my time be less humbly tied than now, – that I might see fruit of my new life’s work.”

Angelica’s sexual encounter with the son of a local landowner, Otto Kefas, is a beautiful hymn to women’s eroticism, rendered in lyrical prose. She asks Otto to walk with her through a field of ripe corn in the moonlight. “‘There is but one field in the world,’ said Angelica, ‘for me.’ And in her mind she added: – For us women. For verily – I think it is like a picture of a laudable love life.” But the narrative voice is aware of Otto’s limitations. Angelica and other women who love are grossly mistaken if they believe of this “god of manhood” that “Otto Kefas’s mind might also be a work of art.”

Ragnhild Jølsen found the impassioned painter Angelica in the pages of Fredrika Bremer. The name itself and her profession and philosophy of life are taken from the novels Presidentens döttrar (1834; The President’s Daughters) and Nina (1835). Both Fredrika Bremer and Ragnhild Jølsen paint Angelica as a young rebel. The Swedish woman, however, dies with paintbrush in hand – the consummate artist. Her Norwegian counterpart is taken out of the novel when she chooses the role of artist, but without having found artistic fulfilment. This marks an aesthetic rupture in the book and a break with the central theme of the earlier books: woman’s longing for the man and for love.

Ragnhild Jølsen broke sexual taboos and courageously showed that she saw body and mind as a whole package. But she was a realist in her depiction of the consequences for the women who abided by their sexual desire. They seek everything in the man – father, lover, friend, and kindred spirit – but they only find physical gratification, self-contempt, and condemnation.

Grotesque Realism

With Hollases krønike, a suite of stories about a rural community, a village devil, and a female painter, Raghild Jølsen has created an invention of genre the stylistic tone of which is far more humorous than that of her previous books. Only the story of artist Angelica has preserved the dark and melancholic tone. Hollases krønike and its kindred work Brukshistorier (1907; Eng. tr. Tales of an Industrial Community) are chiefly told with exuberance and energetic humour.

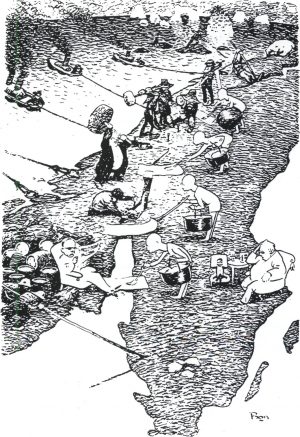

In Hollases krønike, evil Hollas is painted in detail: hollow-cheeked and narrow-shouldered, the mark of Cain on his forehead and stiff-hipped. The writer transforms the realistic everyday level in plastic but exaggerated pictures. Hollas is the most powerful and most evil man in the village. The only thing that has any effect on him is peasant shrewdness and ridicule. Hollas has dung poured all over him, and he dies of cholera, to the accompaniment of roaring laughter from peasants and servants. Strife between evilness and peasant takes on a universal perspective. The simple and the grotesque, peasant and the devil himself, become part of a whole. The village battle continues, because evil and cunning will forever change and reinvent within the setting, and will always afford the village inhabitants coarse amusement and mockery. Despite cholera and death, the village community is indomitable and all but immortal.

Brukshistorier is Ragnhild Jølsen’s final book. Here, the village community and the sawmill are the central characters. The narrative links together social and mythical elements. The collection opens by presenting the sawmill both as a fantasy monster and a workplace. The factory is a “dragon” spewing fire and taking lives, but it also gives “work” and “bread”. And Jens Vaktmann (the night-watchman) communicates with subterranean spirits and knows that there is a devil in every wheel of the machinery.

The common people come more to the fore in the last two books she wrote, both based on popular culture and tradition. They usher in a new emphasis in her thematics, as can be seen on three levels: language is conveyed in flexible bilingualism, alternating between an eastern Norwegian dialect and a Danish-influenced literary language; the outlook on the world opens out towards a horizon of freedom, joie de vivre, and utopia; and, not least, the outlook on the human body, which is seen as a sovereign part of nature as a whole.

Interest in and investigation of the human body comes across in the focus on illness, decline, and death. But the body is, to an even greater extent, synonymous with diversity, beauty, and desire. The male body is described with lust and sensuality. In the chronicle, the narrative voice fantasises about Otto Kefas and perceives him as a desirable object. He is the “most beautiful statue, heavy in the line of every muscle, perfectly hewn and flawless”. When Otto becomes critically ill, two female powers – the angel of life and the angel of death – vie for his fate. Even at that point, the gaze cast upon the man is aestheticised and sensual: “Otto Kefas lay naked on the white bed […] As if of marble was Otto Kefas. Lovely was Otto Kefas.” The angel of life wins the battle.

The story “Den tolvte i Stua” (The Twelfth in the Cabin), from Brukshistorier, deals of “the sand cabin of humankind”, where “man and wife with nine offspring, from the age of eighteen to two, lived, ate, and slept in one and the same room”. Subdued and with a sense of humour, Jølsen depicts female lust for life and fertility. One night Karoline, the eldest daughter, gives birth to a child in the crowded sand cabin: “‘Well, but I’m sure I don’t understand it either, Mother,’ replied Karoline’s voice, ‘I woke up – and then like all of a sudden I’d got a kiddie in bed with me.’” In Ragnhild Jølsen’s work a rehabilitation of the human body is taking place – a way of writing which in her day and age was regarded as masculine and provocative.

The abundantly imaginative visual gallery and the disrespectful dramatic and comic incidents in her final two books can be characterised by the term fantastical or grotesque realism. The tone of the stories contrasts with the stylised, dark, and melancholy pitch that was the domain of the dreaming female characters, but it is closely linked to Jugendstil fascination with the fantastical and demonic. Irrespective of basic tone, all Ragnhild Jølsen’s writing is rooted in an intense, deep sense of life and a strongly visual, subjective perception of the world.

The plague motif and sexual complications in Brukshistorier are suggestive of Boccaccio’s Renaissance work Decameron. Ragnhild Jølsen has much in common with Boccaccio’s popular robustness and his material, physical, and freedom-oriented outlook on life.

Ragnhild Jølsen’s literary output is a long way from the bourgeois, earnest, and everyday approach that characterised Norwegian literature in the early decades of the twentieth century, of which Sigrid Undset, among others, was an exponent. Once what was known as neo-realism had gained the upper hand as aesthetic norm, a large shadow fell – despite all the acclaim – on the first part of Ragnhild Jølsen’s literary production, whereas the critics saw her popular perspective and use of dialect in her later books as an ultimate victory for an objective and more realistic representation. Literary historians, all of whom have had a high opinion of her, kept this point of view, and saw her late-in-the-day realism as her best work. This is a problematic evaluation which has failed to realise that the sensitive, perceptive and the fantastical, exaggerated was a key element in her books and continued to be so.

Translated by Gaye Kynoch