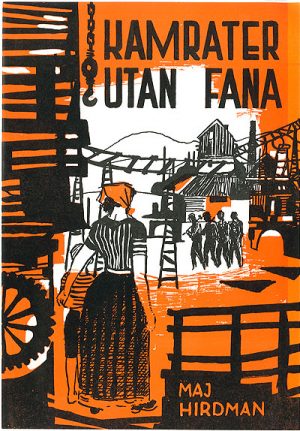

Ansikten (1932; Faces), an anthology of sixteen autodidacts, afforded Maj Hirdman (1888-1976) the honour of representing women. With its candid style, her essay was more personal than any other in the book. Nevertheless, she apologizes for that very quality. She describes herself as “utterly out of my element… [bad at] opening myself up.” Ironically, she compares herself to “contemporary poets and authors” and discovers that she is not one of them. “Where are the other proletarian female poets?” she asks rhetorically, and answers: “I think I know. They have been suffocated, just like the learned woman I carry around in my breast. Where fifteen men fought their way through, fifteen women fell.”

Hirdman’s father was a miner and her mother was a housewife with six children to take care of. She left home at an early age to work as a maid on various farms, where she became skilled at virtually every chore. I törn och i blomma (1944; In Thorn and in Flower), Maja i Dalarna (1930; Maja in Dalecarlia), and Alla mina gårdar (1958; All My Farms) describe this agrarian culture, the world in which she obtained her schooling until late adolescence. At that point her life took a new turn. She took off for a factory town where she met Gunnar Gustavsson, later Hirdman, an industrial worker and future director of studies for the Workers’ Educational Association (ABF). They eventually married and had three children; in 1914, 1916, and 1922.

Hirdman’s move to the city represented an abrupt break with her old way of life, from a largely oral culture to the written culture of the labour movement. From 1911 to 1913, she attended a teachers’ training college in Gothenburg, hobnobbed in anarcho-syndicalist circles, and applauded the philosophy of action. Her diaries testify to the zeal with which she threw herself into an intellectual lifestyle. She quoted and discussed Strindberg, Nietzsche, Spinoza, Plato, and Wilde. She planned a series of books – one about working-class women, an autobiography, a popular history – in her quest for “the way out of degradation.” She also outlined a “Swedish morality tale […] about a miner’s daughter and her dreary battle against ignorance.”

Like Arvida in I törn och i blomma, she is grateful for the opportunity to peer into the treasure trove of great ideas. Arvida explains how much she needed the book learning she obtained through her fiancé: “I was so abysmally behind in everything. I had sat on the milking stool until I was nineteen, couldn’t even spell right, although I was best in my class.”

Arvida in I törn och i blomma is nineteen years old when she attends her first Socialist meeting. She runs into Erik, an eloquent agitator who is soon to be her fiancé. A “denizen of urban culture”, he provides her with access to something she has not experienced previously:

“Never before had I met someone with whom I could share my inner world, who could get me to talk about everything I thought and felt. I had always stuffed all that in a dark corner of my mind, where it was destined to remain until toil and hardship had ended my days. That’s the way my mother had lived, and all my aunts, and all the women I had ever met or heard about.”

The stage was set for conflict. The dizzying encounter between the girl on the milking stool and the great thinkers nurtured the roots of disharmony that was to suffuse much of Hirdman’s writing, manifesting in clashes between high and low, between “men’s work and women’s love” – and the insecure sense of identity as a writer that shines through in the essay from Ansikten.

Hirdman’s journey from diarist to professional author was long and bumpy. She tried to write at the same time that she ran a household, took care of children, lived in poverty, and suffered one illness after another.

Anna Lenah Elgström was one of the first literary figures with whom Hirdman corresponded. Hirdman wrote about a miscarriage and expressed her desire to “be worthy of approaching the temple of literature and art where you live and which I have gazed at in my dreams ever since I was a child.” She reported in her first letter (1915):

“The manuscript of ‘En gravid kvinnas hunger’ (The Hunger of a Pregnant Woman) has long sat on the desk of Social-Demokraten. It’s not the kind of thing that gets read – or that is understood if anyone bothers to read it. I beg you to read it and, assuming it doesn’t require too many changes, send it to the newspaper with a kind word or two… The first part can be deleted without any harm done, but the story of the pregnant woman’s hunger is as true as can be. I would throw it on the dust heap otherwise.”

She managed to publish poems and short stories, particularly in the newspapers Brand, Social-Demokraten, and Idun, but her submissions were frequently rejected. She was 33 when Anna Holberg (1921), her first novel, was brought out. The book was as topical as could be. A number of men published novels that abandoned the violent or impious doctrines of socialism for a religiously flavoured humanism. Hirdman’s heroine is a Young Socialist agitator who grows increasingly sceptical of the party’s modus operandi. An alternative lifestyle ultimately takes shape, that of motherhood.

The political theme is subordinated to the animated portrait of a defiant and thoughtful young woman. Her journey takes her through a series of milieus in class society, including a sanctuary for mothers, in quest of a way to live her own life, a goal to strive for. Hirdman’s style is as nimble as Strindberg’s, often gently ironic. The central conflict is between doctrine and life. The discovery that the agitators do not practice what they preach causes Anna’s convictions to waver. That goes for the pastors who “live in luxurious rooms with every possible comfort while propagating the Christian gospel of self-denial.” And it goes for the anarcho-syndicalist genius who despises “slave labour” grants himself the right to steal from a worker, a member of “the great herd.”

Anna takes advantage of her ‘female intuition’ to expose the hypocrisy of the ideologues. The problem that dominates the novel is that an inquisitive woman, furious at the duplicity of both society and activists, finds no political or intellectual venue where she can integrate her incisive thought, common sense, and instincts into a coherent social critique.

From that point of view, her conversion is more of a defeat than a happy ending: the search, struggle, and critical faculties that had animated her existence are obliterated by the idyllic mother-infant relationship. All that remains is a woman who joyfully but resignedly tends to the “sweet little Goldilocks” in a cottage she can call her own.

Dreams in Locked Rooms

After her first novel, Hirdman worked hard to become a professional writer. Människoträsket (1922; The Human Marsh), Kamp (1928; Struggle), and De förlorade barnen (1934; The Lost Children), the books of short stories she published in the following decade, feature a recurring conflict between female nurture and the remorseless world of men. The idyll in the final lines of Anna Holberg now raises more questions than it answers.

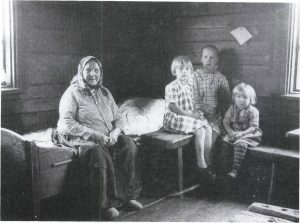

Människoträsket, part of which was written before Anna Holberg, is dominated by wretchedness. The awareness of poverty’s moral consequences is typical of the decade’s proletarian literature. The pathos of the short stories embraces children, mothers, life as it is actually lived. The most obvious example is “Det enda som blev skrivet” (The Only Thing That Got Written), a heart-rending story that describes the inner workings of an infanticide. She is a poor working-class mother of three who has not had a good night’s sleep for five years. Some nights the devil appears and berates her for not having followed through on her plans to write an epic about poverty and its brutality. What is holding her back?

One day she summons up every ounce of her strength, dispatches her morning chores at lightning speed, sends the oldest child out to play, puts the youngest one on the floor with new toys, and starts to write. The blood courses through her veins; her mind is “oddly dispassionate”. She comes across just the right expression, prepares to commit it to paper. But right then the baby craves her attention. She gets a new game going and manages to recapture the errant expression, but the situation repeats itself. The tragedy, which she retells in her own voice, nears its climax. She loses control. The child dies and she is taken to gaol, where she records her version of what happened: “the only thing that got written”.

“I flew up as if I had been stung by a bee, took hold of her and slammed her against the floor, over and over again. I was so furious that my whole body trembled. Just then a neighbour opened the door. I can still see her freeze in horror as I caught sight of Ulla’s motionless, bluish white face. Blood ran out of her nose, dripped onto the floor and mingled with her golden curls. I can’t describe what I felt at that moment – I don’t think I felt anything.”

(»Det enda som blev skrivet«, Människoträsket, 1922)

Kamp and De förlorade barnen leave heart-rending pathos behind. Hirdman’s style is subdued and restrained, reminiscent of fairy tales and with a childlike proximity to the inexplicable. The new mood also reflects a thematic change. The precarious ambivalence and inner struggle in “Det enda som blev skrivet” have run their course. Motherhood is now a matter of course, and only daydreams are left to compete with the all-embracing reality of the home. The narrative style liberates the female characters – not to resolve the conflict between their world and that of men, but to imagine a utopia of happiness and bliss.

Practical Reason

I torn och i blomma invokes the down-to-earth qualities of a housewife as a means of escape from the dichotomy between the world as ideal and reality: roll up your sleeves, scrub and sweep. The book replaces the dreamy housewife with the worldly-wise, poetic, and temperamental Arvida, presented in a dramatic and graphic vernacular.

Arvida describes her childhood, youth, and marriage during the first few decades of the twentieth century in I törn och i blomma against the backdrop of World War II and its privations. In that sense, the book is a companion piece to Elin Wägner’s Väckarklocka (1941; Alarm Clock), with its appeal for peace on earth. While depicting poverty and hardship, the story never loses sight of the joy that can be experienced by doing for others in a caring community.

Hirdman never made a genuine breakthrough. The Novel of the Year Award that Uppror i Järnbäraland (1945; Uprising in Järnbäraland) received was the closest she came to being truly appreciated. Her last books suggest that she had accepted her place in a culture far removed from the ruling elite. She assumed the role of someone who passes on tradition, a storyteller who reminds her contemporaries of the way it used to be.

Alla mina gårdar, Hirdman’s final book, is her only attempt to employ an explicitly autobiographical form. But the narrative voice is light-years from what modern literature is accustomed to – no solitary individual who sounds the depths of her soul and dissects her battle with time and civilisation, but a woman whose roots and situation in life can be traced back to the oral tradition of agrarian society. Nevertheless, modernity was the springboard of her writing career. Overcrowding, children, and drudgery may have robbed her of certain intellectual and wilful qualities. In their place came the great struggle between the dream of motherhood and the world of men. In exposing the conflict and search for an identity, Hirdman crafted a new language, a spirited voice for an ambivalent generation of women.

Translated by Ken Schubert