Since Clara Raphael’s cry for help in 1850, the thirst for knowledge had spread among women of the bourgeoisie. One of the many voices to be heard during the 1880s was that of Olivia Levison. In 1884, in the newspaper Politiken, she wrote of daughters:

“[…] bring them up to rely on themselves, equip them as you would equip your sons, teach them to occupy the years of their youth collecting material for the edifice to be constructed by their future, allow them the boldness bestowed by confidence in one’s own ability. Someone thus developed can safely be left to tackle the vagaries of chance on her own: married or unmarried, that is no longer a case of life or death.”

Young women were also pining in stories written about them: – “Father, I would like to learn something, take lessons –”, we read in Olivia Levison’s Konsulinden (1887; The Consul’s Wife). This request is turned down in no uncertain terms!

Exchange between father and daughter in Olivia Levison’s Konsulinden (1887; The Consul’s Wife):

“‘You have been to an expensive school – which costs a great deal of money, my dear girl. What use have you of it? Ladies are always clever enough, that is not what counts.’

‘But I would put it to use, Father, afterwards I would give lessons to children and earn…’

‘That is all we need!’ shouted the merchant. ‘Have you taken leave of your senses! Should I allow my daughter to give lessons! So the word would be that now things were in a really bad way, that now I had to – not a soul would give me credit!’”

– “She craved a calling, but it was of no use to talk or complain about that kind of thing,” we learn from Illa Christensen’s “Dagtyve” – og Arbejdsdage (1889; “Idling Away the Days” – and Working Days). She gives up!

– “Why does Hinding not give me my money. Then he would be rid of me, and I could learn something worthwhile and provide for myself,” says the daughter of a deceitful stepfather in Adda Ravnkilde’s Judith Fürste (1884). Desperation sets in, and she gets married!

“What would become of her now? […] That nonsense about going out to be a teacher – she didn’t kno w anything.” So writes Amalie Skram in Constance Ring (1885). Apathy sets in, and she gets married!

These heartfelt sighs in Modern Breakthrough novels have the resonance of clipped wings, of a woman’s life spent cooped up in confinement. There had already been women in the 1840s – Henriette Lund and Mathilde Fibiger, for example – who had complained of feeling cheated. And by the 1870s and 1880s, the daughters of the bourgeoisie were still obliged to see their schooling come to an end when it was time to be confirmed. Up until confirmation age, they had received an elementary education at an institute for girls, while the more ‘extensive’ education was attended to by tutors, either in the girl’s own home or that of a friend. The grandest of the bourgeoisie did not send their daughters out of the house at all; they employed a governess who acted as teacher, companion, and chaperone.

The school reformer Nathalie Zahle made a tart comment on this educational practice. In her opinion, the system actually only aimed at making a woman who “could be enjoyed by someone else or used by him” and she reproached “all the striving towards the young girls being able to speak, however badly, one or more languages, develop, more or less perfunctorily, certain skills such as music, drawing, or painting”, because by so doing the girl is prevented from “developing a personality and making it robust and distinct, robust so as later to support development of the more individual talents, too.”

The capitalisation of societal economy now created a more sympathetic ear to Nathalie Zahle’s ideas on education; the schools she set up over the years were pioneering in their endeavours to qualify women to meet the needs entailed by this change.

Nathalie Zahle, however, put it differently: by making sure a woman got a decent education one was also making sure that she developed her “human nature, trusting that the female and thereby the maternal aspect would, of its own accord, in accordance with its disposition, simply by virtue of the essence of truth, come into its own in due course.” Time and again she stressed marriage as women’s “most wonderful lot in life”. She would not hinder “a single true marriage” – but she would do her share to “throw suspicion on and hinder the false, the unhappy ones.”

Nathalie Zahle’s verbal balancing act between Romanticism and realism walked the same tightrope as the rhetoric of Dansk Kvindesamfund (Danish Women’s Society) and corresponded to the very real paradox caused by incipient emancipation. It was only at this point, when the Romantic ideal of woman was about to be confined to the past in practice, that the Romantic project, the “true marriage”, could be implemented. This required that a woman could marry a lover without having an eye to his prospects as breadwinner. Or, in other words – it required women to be able to support themselves, to have knowledge and education.

Nathalie Zahle, Om den kvindelige Uddannelse her i Landet (1873; On Women’s Education in Denmark):

“It is my belief that nothing would do more to preserve and protect the true nature of woman, the female nature in the innermost heart and the depths of the soul, than, from the earliest age, calmly working on personal development, without any subsidiary motive, whilst, on the worldly scale, to create for oneself an autonomous occupation, independent of any relationship to the man.”

It was, therefore, not mere rhetoric when Nathalie Zahle preferred to strike the ideal rather than the financial chords. No matter how much the different factions might disagree, whether the lack of learning was described in fiction or non-fiction, the issue of education nevertheless involved a common endeavour: striving towards ‘cultivation’. A dimension of a general education that, to Nathalie Zahle’s mind, resulted in “the essence of truth”.

In accordance with this, women of the Modern Breakthrough constructed their novels as a process of cultivation. That this seldom succeeded, that their Bildungsromans turned into ‘breakdown’ novels, is not because they were bad writers, far from it, but because the novels reflect the twofold nature of modernity: liberation to exercise personal authority is simultaneously a setting at liberty, a loss of control. Erna Juel-Hansen, characteristically, came closest to filling the genre – of all the female Modern Breakthrough writers, she had the greatest confidence in headway being made. As with “Enlig” (1885; Single), her Bildungsromans are buoyed by an optimistic belief in the possibility of liberation and a will to – despite everything – project a whole female identity.

Out of the House of the Father

Erna Juel-Hansen (1845-1922) was a modern woman. In her work, in her marriage, in her writing, and as a mother she experienced for better or for worse what it meant to be of a radical and emancipated disposition. In 1871, free and dauntless and all alone, she explored Berlin – not because she was on a tourist trip, but because she was educating herself. This was in every respect a breach with the woman’s role; nor was her fiancé, later husband, lawyer Niels Juel-Hansen, pleased, even though she assimilated Froebelian pedagogic theory in preparation for their shared perspective on life. She was, it seems, also modern in her love life: she married Juel-Hansen because she loved and felt desire for him, and not only did she work, like him, she also worked together with him. They set up and ran the first kindergarten in Copenhagen, later expanded to “realskole” (a form of primary and lower secondary school).

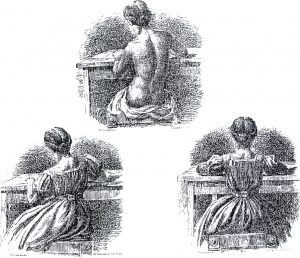

She was also, however, active outside their partnership – both at the outset, when the kindergarten needed extra working capital, and later when her husband became increasingly depressive and was eventually admitted to a psychiatric hospital, Sct. Hans Hospital. She provided for her four children with the money she earned from translation work – Dostoevsky in a fine blend with English popular literature. In 1884 she set up an institute of physical education for women on Købmagergade in central Copenhagen, a good location for her clientele from the bourgeoisie. To her great annoyance, she was obliged to cease operations in 1889 because of low attendance figures. This could have been due to a growing number of competitors in the market, or perhaps because her health propaganda was a step too far; one of her measures was the introduction of shower facilities, which were unheard of given that ladies of the bourgeoisie were not accustomed to full nudity! Her literary output might also have been a hindrance – En ung Dames Historie (1888; Story of a Young Lady) undoubtedly cost her dear.

Her ability to do all this was largely due to the fact that her father, the doctor A. G. Drachmann, had encouraged her throughout her childhood and had urged her to get an education. She could not take the upper secondary school final examination – she was a woman, and her application for dispensation was turned down. She just managed to miss out on the process of development that started with the University of Copenhagen opening its doors to women in 1875. Instead, she took up physical education – studying in both Paris and Stockholm, where the Ling system of medical gymnastics was beginning to gain ground. She was also one of the first women to benefit from Nathalie Zahle’s reforms when, in 1870, she took the school mistress examination from Zahles Skole.

Pehr Henrik Ling (1776-1839), Swedish poet, fencing teacher, and inventor of an exercise technique that was named after him. Unlike his contemporaries, Ling highlighted the importance of thorough anatomical knowledge as the foundation of all physical exercise. In other words, Ling promoted exercise based on rational precepts. However, he was also influenced by the National Romantics, sharing in particular their interest in mythology. In the words of his contemporary, historian and writer Erik Gustaf Geijer, it was thus his aim to “reform the Swedish people through physical exercises and homeland poetry”.

That she, in addition, became a writer was the result of a chance combination of factors: things were brewing, and she wanted to let them out – all the enthusiasm for health and naturalness that was bubbling up inside her

In the late 1890s Erna Juel-Hansen’s commitment to liberation of the female body led to a campaign for “Dame-Cykling” (ladies’ cycling). Under this banner, in 1896 she wrote a series of articles for the magazine Idræt (Sport), in which she gave the ladies instruction in “Kunsten at Cycle” (the art of cycling):

“It is a fact that ladies, with great ease, acquire dexterity in balancing on a bicycle and steering it tolerably well, and a large proportion of them think that is the end of the matter […] But that is a great mistake. A lady rider who does not learn ‘the art’ from the very outset will soon know to her cost that over-exertion, serious breakdown both for her own person and the machine, are the consequences of having taken the matter too lightly.”

; her brother was Holger Drachmann, and she was thereby born into the circle around Brandes, whom she admired and believed in throughout her life; and she was a woman! Being a modern woman, not only did she have to battle publicly for her belief in “Sandhed og Sundhed” (truth and health), as she expressed it, but she also struggled at home with her husband’s continuous scepticism based on her gender. On top of this, she had the double work load and the constant pressure to be up to the mark at all times. As a writer, she could take a step back from her own person – structure the coherence that was hard to spot in the daily round.

Conversely, her writing activities also led to an intensification of her practical difficulties – because she was a women! Like most others of her sex, she made her debut under a pseudonym, hers being “Arne Wendt”. This pseudonym cunningly indicated her identity by means of a wordplay (if Arne is “Wendt” – turned around – it becomes Erna), while at the same time betraying a woman’s insecurity when setting forth into a traditionally male domain. With Erna Juel-Hansen’s characteristic honesty, she soon abandoned this game of hide-and-seek with her gender. As soon as she published Sex Noveller (1885; Six Short Stories), she used her own name, and possibly as a subconscious apology for her ‘impudence’, she dedicated the book in “high esteem and gratitude” to Georg Brandes.

Erna Juel-Hansen’s oeuvre can be read as a serialised Bildungsroman, even though only Terese Kærulf (1894) and Helsen & Co. (1900; Helsen and Company) are directly linked via characters and storyline. Her first published novel, Mellem 12 og 17 (1881; Between Twelve and Seventeen), dealing with three pubescent girls and their various modes of accessing the mystery of sex, can thus be seen as an ‘overture’ to En ung Dames Historie. Similarly, Margrethe Holm from this story is found on the periphery of the group of characters in Terese Kærulf,which picks up where the teenage girls’ books leave off, by depicting the adult woman. The continuation of Terese’s story is then found in the marriage novel Helsen & Co., while the older woman, who could be Terese, but is not, is portrayed in Henriks Mor (1917; Henrik’s Mother).

Terese Kærulf puts story and weight to the ambitious literary project of reaching a position in which women’s lives – not only in the fullness of love but also in the course of time – reflect a human identity. When the novel opens, Terese is twenty-three years old and on a study trip in Berlin. She is alone in the world and, incidentally, the outcome of a misalliance between a daughter of the bourgeoisie and an artisan. As Terese – and the novel – sees it, she has inherited the best from each of these two environments, and her plans for the future involve combining her mother’s appreciation of beauty with her father’s robust desire to do something with his hands: she wants to be a craftswoman.

Terese is not ‘a finished product’, however, as becomes apparent when her resolve is crossed by that of another. She knows that her friend, Heinrich, is going to propose to her, she knows the moment it will happen, but she does not know what her reply will be until she hears it: “‘You love me, Terese, want to be mine, oh, say it!’ She closed her eyes; even if her life depended on it, at that moment she did not know if she meant no or yes. But what she whispered was a yes, expelled in a sigh.”

Terese answers in the affirmative because she only has a verbalised relationship to her intellectual, purposeful side – and that side is highly compatible with Heinrich, a member of Berlin’s radical intelligentsia. Her other side lies passive until Heinrich’s kiss awakens her “disgust”. Her body then makes itself felt in “a purely physical distaste” for his large, stout bulk.

In Erna Juel-Hansen’s Terese Kærulf (1894) the central character is obsessed with a horror of being smothered – in Berlin’s city crowds and in the man’s body:

“She instinctively turned away, felt the grasp of Heinrich’s arm trying to lift her up above the throng, but in vain. She was besieged, squeezed into him with face and mouth pressed against his solid body. She was close to choking and felt a moment of mortal dread, and also disgust, almost hatred towards this large, heavy body, which seemed an impediment to her breathing.”

It is primarily this realisation – with Heinrich’s resistance to her plans for financial independence being but a secondary cause – that leads her to split up with him.

Safely back home in Copenhagen, Terese achieves a hard-won top position in the needlework department of a modern department store. It takes some time before her body gradually emerges from all the work with fabrics and threads; when it does, however, it does so with a vengeance! She falls in love with a student reading theology, a man in the throes of religious and moral qualms and, incidentally, also a man remarkable for his handsome appearance. Meanwhile, she has forgotten to consult with her head because the man is – it turns out – not only weak, he also applies double standards. When Terese offers him her body, in “free and proud abandonment”, he runs away from her and goes off into the Copenhagen nightlife – collar turned up and hat pulled well down – where he satisfies the desire with which he will not defile his intended wife’s body. Accordingly he, too, gets his marching orders.

As in the male Bildungsroman, Erna Juel-Hansen sends her woman into a period of homelessness in which she gets in touch, via the people she meets, with aspects of herself that she then incorporates into her identity: the demands of the body and the demands of the mind. But Terese is not yet whole, she has not reached the position where sexual and social appetites fuse. Terese Kærulf ends in a ‘male’ position, where the body is, for the time being, at rest: “Work, art, awaited her, and by means of them she, like the man, looked into a full, optimistic, and secure future.”

It took Erna Juel-Hansen six years to continue Terese’s story, and first she had to walk Kærlighedens Veje (1895; The Ways of Love), a novel that displays a bitter-sweet understanding of sexual homelessness in the daily grind. With Helsen & Co.,she nonetheless endeavoured to bring Terese home – to wholeness and health (as can be construed from the ironic sounding title: helsen = health; & Co. = the whole concern).

At the opening of the novel, it would seem that nothing less than an ideal is about to be rendered real when Terese Kærulf and Erik Helsen decide to formalise their mutual affection and at the same time enter into a business partnership in the cabinet-making enterprise Helsen & Co. Here, there is marriage between man and woman, body and mind, love and work. But the novel ends with Terese having to sing the praises of resignation after Helsen has ‘strayed’ and the business has taken on a new partner, artistic and affluent Jakob Mendel. As the novel proceeds, an increasingly depressive tone is heard, which is only held in check by matter-of-fact and dry ‘bookkeeping’ – a form of minute-taking that is a long way from the bright tone that gave En ung Dames Historie, in particular, its crispness.

With this bookkeeping style, Terese’s interpretations and misinterpretations are meticulously recorded and corrected. The tension in the novel stems from a narrative voice that is not at all sure either. Might Terese not be right after all? She is emotionally right, at least, given that she bases her happiness on the idea that it is possible to be both ‘wife’ and ‘partner’: “Indeed, she would be his assistant, for that would bring with it the even sweeter delight in living life in and for him.” With these phrases, however, their roles are already imbalanced. The business partner, intent on validating her identity through work, is reduced to “assistant”. The wife, intent on finding validity by abandoning herself in love and forever losing herself and reconstructing her identity in their married life, has nearly ousted the business partner. And this is the very balance that Terese has increasing difficulty in maintaining.

Powerless in the face of this division, she falls back into a Romantic claim to the totality of emotion – and in so doing the role of partner is further undermined, eventually vanishing definitively when Mendel takes over her position in the business. Terese – and the narrator – is forced into a ‘double-entry bookkeeping’. Crushed by her knowledge of Helsen’s adultery, Terese again brings logic into her life by constructing a division between “instincts, urge, desire” on the one hand, and, on the other, “emotion, substance, variety” in their married life. Helsen’s affair can then be filed under the less significant ‘urge’ heading, and the Romantic dream of wholeness can be re-established. In relation to her earlier self-perception, the ‘explanation’ left in Terese’s clouded mind is a failure of cognition, but this is the depressive status towards which the novel has been compelled all the way through.

Helsen & Co. is a breakthrough in the canons of modern literature by virtue of its insistence on the continuous development, gradation, and final dismantling of the body’s volition in sexual desire. There can be no doubt that in Terese’s case sensuality has become an element of her self-perception:

“Now her blood was kindled by his flame, and she discovered a completely new delight in his arms […] She was transported into an exhilarated ecstasy, and she could tell from Helsen that he was not a scrap better.”

This sexual qualification of the relationship continues throughout the marriage – as satisfaction or as loss. The birth of their first child is also described in eroticised terms, even though it is this very child that intensifies the antagonistic tension in their relationship. The child is both the token security of the couple’s love for one another and a wedge that is driven between them. Terese loses the sexual identity in relation to her husband because he gradually overemphasises her maternal function while she compensates by keeping him in the role of lover in her fantasies.

Loss of sexual identity in Erna Juel-Hansen’s Helsen & Co. (1900; Helsen and Company):

“He no longer called her ‘Terese’ or ‘dear’ or simply ‘Madam’. Now it was ‘Mother’ and then ‘Mother’ again or ‘dear Mummy’. It was as if she saw a shift occur in his heart, where his wife, his beloved, was displaced by the mother of his child.”

The ‘breakthrough’ aspect of the novel in this respect is that it does not ‘cheat’. In contrast to Nathalie Zahle’s conviction, “the female and thereby the maternal” do not turn up of their own accord in conjunction with the development of “human nature”. Motherhood is, on the contrary, a new field of conflict in the text, precisely because Terese has more than enough of what Nathalie Zahle zealously called for: a “robust and distinct” personality. Terese battles against loss of identity in her maternal role at the same time as she battles on the other front – with her husband – to remain in an ‘erotic’ vacuum: “Captivated by her passion, she had been on the way to losing herself – indeed, perhaps him also.” Cognition is complicated: in order to hold on to herself she has been on the point of “losing herself” and also of losing the very sexual identity that had earlier been a revelation – because unquestioning instinct cannot include ‘the other’, neither husband nor child!

Another new departure is that by taking the cultivation project to its terminus – in a sense Terese goes home to the bottom of her being – the novel undermines its own trajectory. Cultivation encapsulates the individual, the energy cannot combine that which is individual and that which is societal; Terese, Helsen, and their two children move each in their own system, like celestial bodies in an empty universe. The narrator’s bookkeeping is all that keeps the accounts in balance.

The late work Henriks Mor can be read as a further denial of the ‘cultivation project’. In this case, the child who could not be combined with sexual timelessness has returned with a vengeance. This is not as a continuation of the story, but as a nightmarish repetition of the closed relationship – this time between mother and son. Whether it is the son who fetters the mother or the mother who fetters the son is unclear. At all events, it so happens that the newly qualified, newly employed, and newly engaged Henrik contracts a mild case of tuberculosis. On the verge of cutting the apron strings, he abandons any resolve to live an independent life and demands unconditionally that his mother does the same. Just as she has spent years living on an earlier desire for an absent husband, so now she is ensnared in her son’s project in life: to keep the tuberculosis on the threshold, neither completely out nor completely in.

Henriks Mor takes the women’s ‘development’ project into the realm of the psychological thriller. Why?

The reason is that the ‘development’ of woman, contrary to that of the bourgeois man – which is consummated in union with the one and only – only begins to assume its personal form at the point where that of the men ended. Nearly all the female Modern Breakthrough literary processes of development are pursued through marriage – and thereby refute the strategy proposed by Olivia Levison – “allow them the boldness bestowed by confidence in one’s own ability” – so…

Terese has plenty of confidence in her own ability. The factor that brings down her project is, paradoxically, a naturalistic version of a Romantic legacy: idealised sexuality. The woman who, in life and attitude, was the most realistic of the women mixing and writing in Copenhagen during the period of the Modern Breakthrough also wrote a body of works that when read as a whole subverts any possible optimism with regard to the process of development. It also indicated hidden forces – psychological and societal – which were beyond the bounds of Erna Juel-Hansen’s artistic remit.

“My mind is paralysed […] I dare not think about Terese’s final chapter yet, for then everything becomes confusion. I do not know what is wrong, but I cannot get down to it – although I actually know exceedingly well how it will proceed,” wrote Erna Juel-Hansen in her distress while working on Helsen & Co.

As a pioneer of the women’s cause, Erna Juel-Hansen represented a fortunate combination of ability and circumstance – it seems as if the writing artist in her ran out of steam. Her last novels were written ‘behindhand’ – the material is there, the modern approach to style is there, but the aesthetic imperative is not. The material does not add up in the writing!

‘Development’– in the Family Forum

Erna Juel-Hansen is – probably – the only woman writer to allow ‘development’ to start from a liberated platform. The main concern of writers such as Therese Brummer, Massi Bruhn, and Illa Christensen was to get out of the father’s house in the first place, a house that – it emerges – was zealously guarded by the maternal monster. Their Bildungsromans are, therefore, mostly in the form of marriage novels.

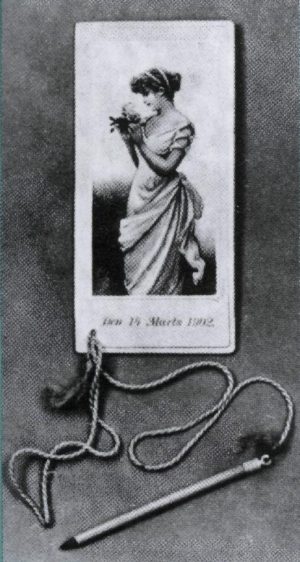

Like Erna Juel-Hansen, Therese Brummer (1833-1896) participated in Henriette Steen’s “tea club”. Her views were of a radical leaning, although she stayed out of the line of fire by publishing her works discreetly under various pseudonyms: “BH”, “Elisabeth”, “Mrs Elisabeth”. By birth and marriage, however, she was allied to the National Liberals and conservative circles. Her radical attitudes are not writ large in her work, but are present via a sympathetic sensitivity with regard to the universe of childhood – and to the way in which woman was tethered with the finest, most delicate thread in the enclosed forum of the drawing room.

The drawing room as apathy-inducing boredom, the woman’s life barely ticking over – here in Amalie Skram’s version from Constance Ring (1885):

“Constance had been trying to stitch a strip of embroidery from her sewing basket. She had long ago forgotten what she planned to do with it. She had read for awhile, tossed the book aside, paced up and down the floor, and sat down again to sew a few more stitches. Suddenly she flung down her embroidery, swung her chair completely around and leaned her elbows on the windowsill. Propping her face in her hands, she stared out at the street with bored, apathetic eyes.”

On the face of it, there is no connection between her widely-read and popular books for children and the rest of her output. Indirectly, however, there is. Therese Brummer wrote for children in accordance with a “good, old-fashioned folktale tradition”. Her purpose was not to instruct the child about “real life”, but to bear out his or her “childishness” as being “the foundation upon which the child shall live in seriousness and play”. Her writing for adults deals with how this childishness is laid waste in the ‘real life’ of women:

“As Mrs Wallin turned the newspaper, the rustling sound broke the silence.

‘Mama, that noise of paper!’ came whining from the sofa.

Mrs Wallin folded the pages away and sat down quietly over by her needlework.

‘Mama, so intolerable I have become – how can you put up with me. Scold me – shake me – you can see how nervousness renders me impossible!’

‘Fortune has been so hard on you, child – that I must be gentle.’

‘Oh, these maxims!’ thought Christy, ‘would it not be far better if Mama said: Do not lie there and idle, but get up and do something.’

She then closed her eyes again listlessly. Eventually she fell asleep.”

The young woman in this scene, Christy, has had her wings of fantasy clipped, so now, with no use of force whatsoever, she is confined to the place, to her body, to her sensitivity. Her mother’s gentleness provides no opposition and thus no counter-images either. Everything takes place on the back burner, rustling, whining, quietly, gently, and listlessly. Soporific boredom – and it is thus that the drawing room disables female growth in the novel Som man gifter sig (1888; As You Marry).

Christy has spent her youth waiting for the man of her choice, and when he marries someone else she is left with the prospect of continual confinement, with her mother or in a marriage of convenience. Indolent and slack, she marries a landowner – who changes his manner as soon as the deed is done. His clumsy wooing turns into coarseness and brutality. Maternal dominance in the drawing room was observed in its subtle and almost invisible existence, whereas the husband is portrayed in loud forms and glaring colours. A grotesque monster, straight out of the fantastical world of folktale. The battle between Christy and her husband is a life-and-death struggle; as such it illustrates, on a symbolic and manageable level, Christy’s painful process of liberation from her mother – a process she must undergo before she can get out! Out to … indeed, what? Once Christy has eventually obtained a divorce, contact is again made to the environmental and psychological realism. Grey tones depict the difficulties encountered by a woman with no education when she attempts to survive the daily round as self-supporting single mother.

The novel ends with the rightful lovers getting each other anyway. On one level this is unconvincing, but on a symbolic level it is credible. Now, once the symbiosis with her mother has been breached, Christy is at last in a position whence she is able to render her desire personal.

Therese Brummer thus has a different weighting in the process of development than does Erna Juel-Hansen. In her second novel, En Kamp (1893; A Battle), the psychological nerve fibres between mother and child again impede personal development. Motherhood, which is the woman’s only creative power, makes not only the mother but also her child a loser.

Massi Bruhn (1846-1895), too, addresses the genre. But in her novel Et Ægteskab. En Fortælling (1889; A Marriage. A Story), the female process of ‘development’ has been narrowed down to a conflict between sexuality and motherhood. In terms of outlook, the wife manifests a clear critique of the Romantic female role which idealised but also reified the female individual:

“In a prosperous home, the wife is the most precious luxury object. She must be cared for and protected, not because she has the human right as equal to man, but because she is the source of existence … mother of men.”

In terms of manifestation, on the other hand, the wife’s sexual rebellion does not lead to an individual process of development, but sets off a course of resignation and atonement in which the parties find one another in a form of mutual ‘cultivation of the heart’. In Alt for Fædrelandet (1891; Everything for the Fatherland), the process of development similarly caves in. This is to some extent because the novel falls apart stylistically: an edgy journalistic style wrestles with traditional narrative; partly because art is literally sacrificed for the cause – the cause of peace, which is the business of the novel. And which corresponds to the schism in Massi Bruhn’s own life. As a member of Kvindelig Fremskridtsforening (Women’s Progress Association) and writer on the journal Hvad vi vil (What We Want), she was working at the frontline of the women’s cause. As author of fiction, she wrote mainly derivative literature. Romanticism clings to subjects and forms alike.

In Illa Christensen’s ‘development’ novels, “Et ubetydeligt menneske” skitseret (1885; Sketch of an Insignificant Person), De smaa Tings Magt (1885; The Power of Small Things), “Dagtyve” – og Arbejdsdage, and En Søn (1890; A Son), it is postponement and the gulf between the parties, rather than the marital relationship, that determine the process of personal development – of both the male and the female party. Nor in this case, however, is the artistic vigour to be found in the process, but in attention to all the hidden agendas underlying the modern, blasé individual’s wishy-washy conversation. In Illa Christensen’s work, the genre is thus wrestling with another modern trend.

This conflict leads to an aesthetic falling away in passages of Adda Ravnkilde’s writing. All sails are otherwise set to navigate the course of the Bildungsroman. In the story “En Pyrrhussejr” (1884; A Pyrrhic Victory), the young woman sallies forth into the world in order to get on in life, to become something: “something great and good, something that matches the strength I feel inside.” But activities cease somewhat abruptly once she has walked into the marriage trap. From this point onward “En Pyrrhussejr” does not take the form of a developmental process, but of a pamphlet-like report in which incident is added to incident in illumination of the oppression of women in marriage. It is not, however, a matter of external opposition alone that obstructs the process of ‘development’ in women. “En Pyrrhussejr” portends an inner resistance to “getting on in life” and an aesthetic resistance to binding writing to reality at all.

In Adda Ravnkilde’s “En Pyrrhussejr” (A Pyrrhic Victory) from To Fortællinger (1884; Two Stories), the women join “Fremskridtets hær” (The Army of Progress):

“And let us but be trampled underfoot. That is the fate of the forerunners. But can the common soldier in battle console himself with his death, if only his country may be victorious, – then we two must be able to do so as well.”

Translated by Gaye Kynoch