“[…] An Everyday Story is not only a consummate story, but stories of consummation,” wrote Søren Kierkegaard in 1846 of Thomasine Gyllembourg’s prose, and in this he was right. As a storyteller, Thomasine Gyllembourg (1773-1856) skilfully manages to make a conflict grow out of an apparently harmonious universe, whereupon it develops and is brought to a head in accordance with its own inner logic, finally signing off in a synthesis.

With her twenty-four stories, Thomasine Gyllembourg consolidated a new literary tradition – the realistic prose story. She shows her reader around in the external forum where everyday life takes place, ornamented with particulars that might seem like knick-knacks, but which all share in the function of making her universe recognisable actuality. She catches the distinctive ambience of her settings and characters by means of very precise language and an abundance of detail conjuring up interiors, outfits, gestures, and speech.

At the same time, her realistic endeavour is extended to the inner forum, the almost psychological interaction that is played out wherever people gather and emotions are generated and complicated. With her ability to tap into silence and speech alike, and in her willingness to embed that which is ‘ugly’ in a realistic context, she in glimpses pre-empts the Modern Breakthrough.

However, Thomasine Gyllembourg also draws solidly on didactic Enlightenment prose. Her narrator lightly sprinkles erudite comments for those readers schooled in philosophy who might be having trouble seeing themselves reflected in her petit bourgeois characters, who are rendered with a mild dose of irony. For the average reader, she presents with all possible clarity an unambiguous distinction between ideal and less ideal – and here, the realism runs out. Meticulous as she is with her depiction of setting and characters, she is equally schematic and devoid of contrast when pointing out the difference between “true conduct” and superficiality.

In 1846, when reviewing Thomasine Gyllembourg’s final work, To Tidsaldre (1845; Two Ages), Søren Kierkegaard added the affectionately mischievous comment that her oeuvre persuades one “to remain where one is”.

This is true inasmuch as its players as a rule realise their innate potential – without exceeding their personal parameters or those of their milieu.

“Every life-view knows the way out and is cognizable by the way out that it knows. The poet knows imagination’s way out; this author knows actuality’s way out; the religious person knows religion’s way out. The life-view is the way out, and the story is the way. In the context of the categories it is readily apparent that no one can reconcile with actuality as this author does, precisely because his way out is actuality.”

Søren Kierkegaard, To Tidsaldre: En literair Anmeldelse (1846; Two Ages: A Literary Review).

Her works also appeal to another reading, however, one which does not allow itself to be completely ‘persuaded’ by the well-bred voice. Thomasine Gyllembourg’s consummate and ‘meticulous’ style is a security that also permits exploration of bold topics. The arbour roof compassionately offers shade to the lovers’ desire and agony, and an elegant, restrained appearance will hide passion from everyone other than the one in the know – thus, too, the everyday stories’ aestheticisation conceals the contrasts inherent within the person of their author. And it is in the tension between voices of passion and voices of insight into life that her writing flourished.

Domestic Bliss

Thomasine Gyllembourg was the child of a well-established middle-class Copenhagen family. However, her life was not to run along the same lines as those of the majority of middle-class daughters of her day. She did indeed marry young, in 1790, and had a child in 1791, but her subsequent route in life deviated from that of her contemporaries. In 1801 she asked her husband, Peter Andreas Heiberg – who at the time had been living in exile for a year, banished because of his politically critical writings – for a divorce. She was eventually granted a divorce, whereupon she immediately married her lover, Carl Frederik Gyllembourg-Ehrensvärd. She was compelled to give up her son, Johan Ludvig, to the care of others; it was not until 1815, when Gyllembourg-Ehrensvärd died, that she was again able to live under the same roof as her son. This she continued to do, by and large, for the rest of her days, and it was in this living arrangement – from 1831 with the addition of her daughter-in-law, Johanne Luise Heiberg – that she became, in 1827, “The Author of An Everyday Story”.

Having reached the point of requesting a divorce, Thomasine Gyllembourg was also in a position to see her development as a struggle for freedom – as Heiberg had struggled for civil liberty, she claimed her right to demand the realisation of her ideals. Heiberg, however, was not in the least inclined to accept her construction of the message of liberty. When Heiberg received Thomasine’s autobiographic epistle outlining the background for her demand for a divorce, he desperately refuted her accusations against him – at the same time as the lover’s voice he had hitherto rejected suddenly infused his reply: “Most precious, forever loved Thomasine!” he declared, when he realised that she was in love with someone else. But then a completely new variant of the shy Thomasine emerged: the furious “virago”, as Heiberg called her. He had bad dreams about his transformed wife, and it was no less nightmarish for Thomasine herself thus to discover the shadowy side of the person created by married life with Heiberg. The ideal image of woman – which she thought she inhabited – cracked, and that was frightening.

Divorce and a second marriage meant that Thomasine Gyllembourg was not welcome in polite, middle-class society. Social vulnerability did not cause her to go to pieces, however; on the contrary, she became an artist. This departure can be attributed to her earlier marital Heiberg home, in which the foundations had already been laid for a female individual who was capable of more than most.

Thomasine Buntzen, as was her maiden name, went to the altar full of youthful idealism; she believed in marriage as the forum in which emotions would continually find expression, where her husband’s love would validate her as the woman she was – and her expectations were thwarted. For Heiberg was no romantic, but an overwrought seeker of truth who did not hold back with cutting comment when he saw a public or private falsehood in need of exposure. He therefore refused to speak his wife’s language of love, he rebuffed her need for validation – he simply did not believe in the fiction into which this sensitive woman so wanted to inscribe him.

Instead of submitting to her husband, Thomasine Heiberg stuck to her system of values, and in so doing she grew apart from him. Heiberg’s parrying sent her back to her own life, and thus the young, malleable Thomasine became a free person.

However, her new life as Mrs Gyllembourg was not to prove straightforward either. After seven years of marriage, she was obliged to define her understanding of love for her consort:

“And what does one think about the word romantic? To love romantically, I would think. Either, it seems to me, one must thereby understand: to simulate feelings […] or else by romantic love one means: a love that is rare in the real world, that only a few people know how to feel, that does not often exist except in the poet’s imagination. And who would not wish to be loved with a romantic love?”

The yearning for this “love that is rare in the real world” motivated Thomasine to leave her first marriage. She was not “deserving of punishment” – even though she went beyond the bounds of every possible norm – because she saw herself as chosen, whereas most other people, women and men alike, were only allotted an ‘everyday story’. And that was cut according to a more down-to-earth cloth than was her personal story. Immoderate as she was when pursuing her own avenues, she was equally moderate when recording the ‘ideal’ in her extensive oeuvre. Overall, the short stories provide – now and then with some difficulty – a harmonious concord between the tensions that had so dramatic a consequence in Thomasine Gyllembourg’s own life.

“But one day, when we had driven out with Aunt Kjellermann, Peter and Hanne, you again spoke to me those unhappy words that had once before caused me such pain: that you had never really loved me. That time, I did not keep silent, I responded to you with all the quick-tempered heat of youth, I was bitter, and you became so, too, and it all ended with a most disagreeable scene that lasted all that evening and most of the following day and was truly ground-breaking for my life […]

“In the meantime, you had brought me into acquaintance with many very interesting people, our home was lively, our small evening gatherings highly agreeable, full of warmth, inspiration, and pleasure. I trained my intellect in this company, I became cheerful and at ease, and altogether grew both in mind and body, to the wonder of all those around me.”

Thomasine Gyllembourg in Johanne Luise Heiberg: Peter Andreas Heiberg og Thomasine Gyllembourg. En Beretning, støttet paa efterladte Breve (1882; Peter Andreas Heiberg and Thomasine Gyllembourg. An Account, Supported by Surviving Letters).

An Everyday Story

In En Hverdags-Historie (1828; An Everyday Story), Thomasine Gyllembourg leads a young man into a drawing room where there is more vice than virtue. Through him, critical eyes are cast on the “striking lack of neatness and order” in the household, and we gradually find out that beautiful Jette, to whom he has become engaged, is a frivolous young lady with a fondness for finery. He suffers daily from the “incessant sewing of clothes, collars, caps” necessary for the maintenance of Jette’s beauty – not that this suffering can induce him to break his oath of allegiance.

Once Jette’s half-sister Maja has entered the family circle, however, his true ideal is ‘exposed’. The character of Maja infuses the entire story with a sheen of the unique, of a “higher nature” than that of the everyday and familiar. The sewing disappears, meals are served punctually – the tone of the whole household is elevated to a more gracious level.

With Jette on one side and Maja on the other, Thomasine Gyllembourg creates two diverse universes. In the one, she gives a picture of the manners and customs of family life lived on the surface and of a young girl’s upbringing that is content to deal exclusively with external appearances. In the other universe, we witness the specially chosen one who, with a noble bearing and inner cultivation, is equipped for depth of feeling. The first universe has the author’s understanding and compassion, whereas it is the other universe with which she is in total sympathy. However, throughout all her many short stories based on this dual narrative Thomasine Gyllembourg’s artistic skill lies in her ability to combine the two universes in an organic ensemble piece. Like Maja, who brings out the best in those around her, the other ‘special’ characters in the stories contribute generously to raising the level of cultivation in their surroundings – they act from an inner strength, promoting virtue and impeding vice.

While En Hverdags-Historie shows family life in a concave mirror, a number of Gyllembourg’s other short stories reflect family life in a magic mirror. It here shapes the framework for a demonised emotional life that possesses some of its members with trauma and hysteria. In Slægtskab og Djævelskab (1830; Kinship and Devilry) the family is the breeding ground for all manner of madness. In a nightmarish fashion, youth has been visited by the sins of the fathers, and the three brothers in the parent generation control their children by employing measures such as suicide, silence, and enforced misalliances. Here Thomasine Gyllembourg has created a plot that no quiet diplomacy will resolve, and an all-overthrowing catastrophe has to intervene before the various threads can be unravelled.

“Haldorf sat in the sofa, asleep. He sat upright with head bowed, eyes closed, and hands folded. On a stool at his feet sat Rosine, also asleep, resting her head on the sofa, so close to her father’s knees that her locks of hair touched them. That picture, representing Oedipus and Antigone, was vivid in Robert’s memory. The similarity was striking. Nor was the Eumenides’s support lacking, for in the same sofa, behind Rosine, in the opposite corner, lay the body of the dead child.”

Slægtskab og Djævelskab (1830; Kinship and Devilry).

Father and daughter, brother and sister – the incest motif lurks in many of Thomasine Gyllembourg’s stories. In Den magiske Nøgle (1828; The Magic Key), De lyse Nætter (1834; The Light Nights), Jøden (1836; The Jew) and Maria (1839), behind the complications caused by love between the young people who believe themselves to be – or are – siblings, there also lies concealed a generational conflict, which can be read as a thematisation of a wider familial complexity.

When Thomasine Gyllembourg wrote her everyday stories, the nuclear family was still a new phenomenon, and she herself had lived through a considerable part of its cultural genesis. “The Author of An Everyday Story” positions herself midstream between the old family with its awareness of lineage and the new family with its orientation towards the individual, and from this vantage point she views the evolution of the family, weighs up loss and gain, and exposes the inherent cracks in the foundation of the nuclear family. The incestuous plotline is Thomasine Gyllembourg’s interpretation of the change in family structure, it is a picture of a new configuration that had not yet found its ‘culture’ and its modus vivendi.

In all these stories, it is the father who conveys the true values from his own generation to the young generation. But he is also the cause of the love conflict between the young people, because his past holds an unatoned-for sin – a child who, in a figurative or concrete sense, has not had his or her paternity acknowledged. Tension between the old and the new family structures thus features as an existential question asked of the individual – ‘who am I’ – and it must be answered both socially and psychologically before the nuclear family can bring its generation of children into the world.

In Maria and in De lyse Nætter the young lover has to die, because the way to the beloved is definitively blocked by the mental or the actual kinship. In stories such as Den magiske Nøgle and Jøden the blockade is, on the other hand, surmountable. In these two cases, the men realise that they must love their women from a distance, and it is via this resignation that they are found worthy to enter the intimate forum of the nuclear family. Their paternity is then acknowledged, and they can marry.

In Den magiske Nøgle (1828; The Magic Key) a wealthy old gentleman reveals, on his deathbed, that he is Rudolf’s father; Rudolf has grown up in the belief that he is the son of the pastor and the brother of Pauline with whom he has always lived.

“Imagine my delight: Pauline is not my sister! My father’s spirit, forgive me my joyous sentiment in the same hour as I come from his deathbed, but if only he could see my gratitude! In life he refused to acknowledge me, but in his dying moment he paid me for his injustice with a thousandfold kindness in taking away the poisonous maggot that has so long gnawed at my equanimity, by saying to me the all grief-healing words: Pauline is not your sister.”

Modern Matrimony

When Thomasine Gyllembourg defied morality and gave herself to her lover, a division was forged in her disposition, never to be neutralised. Was she a ‘virago’ or a true romantic woman? Was it possible to bridge the unique and the everyday? Should life be governed by passion, or should she have availed herself of common sense? This split is a motive force in her writing, but it is not ascribed to her female characters. With few exceptions, the young women are the stable pivotal points in the stories. The male characters, on the other hand, carry the tension and drive it forward in the texts. They work up the highest state of passion, they are willing to sacrifice societal respect in order to win the object of their desire, and they often end up in the most painful resignation before achieving the state of contented love. Their irrepressible emotions are the mystery from which Thomasine Gyllembourg tries to assemble her own contradictory personality. At the same time, however, this curiosity about the male sex also discloses the male mystery to the female reader who lived within a nuclear family in intimate proximity to a character she did not know very well.

In 1809 it was not unusual for a husband to read his wife’s letters. That was the year in which Thomasine Gyllembourg conducted a confidential exchange of letters with her friend Lene Kellermann – and thus only a few extracts have survived. The correspondence would seem to have centred on a delicate issue: should she – Lene – embark on just as controversial and difficult a journey as Thomasine had done eight years earlier? Thomasine’s reply is, out of consideration for unauthorised readers, expressed in a cryptic code, but it does contain long passages that illustrate the dichotomy she experienced on the issue of her earlier actions:

”Know you, my Lene! For you I dare tell all my thoughts, know you, that there are moments when I – I cannot say reproach myself, but censure myself, for the only lover I have ever had, and whom I have made my husband. H[eiberg] did not deserve me, I say that freely, but nor was I completely entitled to throw myself into such a labyrinth, which I could not in an honest fashion get out of with so terrible a step as I took, and the consequences of which I had not in cold blood estimated […].”

In Johanne Luise Heiberg: Peter Andreas Heiberg og Thomasine Gyllembourg. En Beretning, støttet paa efterladte Breve (1882; Peter Andreas Heiberg and Thomasine Gyllembourg. An Account, Supported by Surviving Letters).

Ægtestand (1835; Marriage) is, in many ways, a close retelling of the Heiberg marital story, merely with the not inconsiderable difference that husband and wife – Lindal and Sophie – are strengthened by the crisis that erupts when Sophie falls in love with passionate Sardes.

The progress of the story demonstrates how a sourpuss becomes a lover. Lindal’s and Sophie’s proclivities are elegantly interwoven with the use of psychological motivation. When the story opens, there is a lack of balance in their relationship; Sophie is rebuffed every time she approaches Lindal. In the glow of Sardes’s burning adoration she turns away from her husband – and as she does so, his interest in her is whetted. And at the end, once Sardes has left, the scales find their balance and the marriage becomes “Paradise regained”, as Lindal poetically phrases it. Sophie is clearly the one to have gained, as she ends up with the love-charged husband she had been yearning for at the outset.

Ægtestand is Thomasine Gyllembourg’s only depiction of marital life as lived within the ‘domestic bliss’ of a modern family. She lays bare the wordless miscommunication between a somewhat tyrannical man and a sensitive, unassuming woman. Lindal is thus not at all like the elderly patriarchs in the other works. He is the prototype of the nuclear-family father who ruthlessly sets the parameters for his son’s and his wife’s conduct in his own male image. But he is not allowed to persist in this style. Thomasine Gyllembourg puts a stop to that by bringing in “this sweet, plaintive nightingale, this Sardes”; against the backdrop of Sardes’s “everlasting warbling” Lindal changes his tune.

Civic Virtue and Nobility of Soul

The story of Mesalliance (1833; Misalliance) uncovers a weakness in middle-class culture. The problem was that what Thomasine Gyllembourg here calls “small customs and accepted forms” could be put on like a “frock” – without connecting to body and soul. How, then, was a young burgher woman meant to see the difference between a true and a false suitor, how were she and her sisters meant to identify “the dividing line between the so-called genteel world and the simple or bourgeois”? In this, as in other texts, the answer is found in one word: upbringing. Time and again, Thomasine Gyllembourg shows the ruin brought about by an insufficient, superficial upbringing, and she is particularly critical of how the aristocracy lets things slide with respect to their children’s future.

In the middle of Mesalliance (1833; Misalliance), Thomasine Gyllembourg explains her – and the Danish bourgeoisie’s – complicated concept of dannelse (culture, cultivation). On the one hand, true culture has to be an internalised sense: “so little conspicuous that it cannot be acquired as a talent or put on as a frock, but must be united with the human soul, just as the body is.” On the other hand “however, inevitably many small customs and accepted forms are thereto assumed, which could not be absent without causing offence”. So, invisible and visible all at once, internal and external; she called the combination the “true conduct” – nobility of soul.

In Extremerne (1835; The Extremes), presentation of the relationship between inner and outer cultivation, between burgher and aristocrat, is far more subtle – and more realistic. Here the story itself – and not weighty comments by the narrator – supports the tangled net of contradictions and conflicts that arise when the two classes meet. We encounter the ‘extremes’ of each class – both a gracious and a status-coveting aristocrat and both a gracious and a money-coveting commoner. And it is, of course, decent civic virtue that is able to bridge the class differences: the doctor, Hermes, wins the love of beautiful, aristocratic Gabriele. In symbolic manifestation of the now completed shift of societal power, Extremerne ends with the death of the intractable aristocrat immediately after he has given Hermes and Gabriele his blessing – a blessing they have so long entreated of him.

The only character who really rises above the ‘extremes’ is the Count, who has thrown away his title in order to devote himself to his calling – that of an artist. Mr Palmer, as he quite simply calls himself, decorates – when it suits him, that is –the conservatories of the nouveau riche. This he does most beautifully and, in a remarkable, inspired moment, he creates great art. Once in a while he is permitted to imbibe a little merrily – a form of excess not usually allowed in Thomasine Gyllembourg’s moderate universe.

To Tidsaldre (1845; Two Ages) – Thomasine Gyllembourg’s final work and her cultural-historical testament – encapsulates the changing times, from these good old days up to the 1840s. The second section of the book, the “Present Age”, resembles most of the other everyday stories, while the first section, the “Age of Revolution”, endeavours to capture the enthusiasm and openness that prevailed in her youth.

The revolution in question is the French Revolution of the 1790s, not as a phenomenon of world history, “but only what I would call the domestic reflection thereof”, as she writes in the preface. The everyday perspective is thus given a dimension of historical development that is not otherwise foremost in her oeuvre. In terms of composition, this is achieved by the two ages mirroring one another – and by Thomasine Gyllembourg’s elegant structuring, in which the gallery of 1840s’ characters denounce the open-mindedness of the revolutionary age while at the same time their words and actions disclose their own narrow-mindedness and foibles. To Tidsaldre is thus both a contemporary critique and a historical tale.

In this respect it is Thomasine Gyllembourg’s most ambitious work. With the clear-sightedness of age she points out that morality and manners are both historically and individually determined, that development is not necessarily linear and driven by unequivocal progressive logic, but that it also entails setbacks and decline.

The cultural-historical message of To Tidsaldre maintains that conduct considered immoral according to 1840s’ ethics – revolutionary disposition, impassioned abandonment to love, adultery – is not nearly as reprehensible as the righteous prudishness of the day. The distinction lies in the degree of intensity – the fervent individuals of the age of revolution lived their lives to the full, whereas her contemporary social associations were governed by convention and coquetry. Nobility of soul has turned into surface appearance, and civic virtues have transformed into dull philistinism with the individual rendered anonymous due to consideration for what ‘one’ approved of. The trends identified by Thomasine Gyllembourg in the 1840s thus anticipate the particular modern way of life that would be put to debate some decades later in the literature of the Modern Breakthrough.

Woman as Work of Art

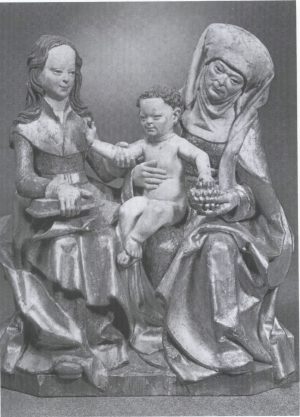

“Is it not as if one can see the Virgin Mary and Child, and with rays around the head, like she is shown in the picture that hangs at the District Governor’s?”

Thus asks a simple farmer in To Tidsaldre, having one morning found young, unmarried Claudine and her son, Charles, asleep in his stable. She is on the run from the moral condemnation caused by her relationship with a representative of the French Revolution, Lusard.

For the next seven years, Claudine lives in an atmosphere of timelessness and standstill. This period of atonement is “shown” with the same radiance as that which surrounds The Holy Mother “at the District Governor’s”. Thomasine Gyllembourg does not only draw on the style of the Renaissance painting; the motif itself – mother and son in ‘sympathetic’ co-existence – is acted out in the story line. Claudine and Charles live totally in one another’s image, and this means that there cannot be any other men in Claudine’s life. Charles is, in every respect, his mother’s dutiful son – until the day arrives when he is old enough to offend against her law.

On that day, the glow around the picture of the Virgin Mary and Child fades, the idyll is under threat; but instead of shattering, the idyll opens out into perfect happiness when Lusard returns, throws himself at Claudine’s feet, and is forgiven for his long, silent absence.

The story Maria (1839) opens with a similar biblical constellation. Maria, Miss Holm, and Maria’s two foster children share a small apartment and run a thrifty household on the income these two industrious women earn by sewing and washing. Where the utopia in To Tidsaldre is allowed to remain unaffected, in Maria it soon comes apart. Unlike the sexually released Claudine, who after her atonement can return to the business of love, Maria’s (Mary) virginity is not merely a temporary condition; it is so deeply bound to a sexual blockage that her rendering of ‘virgin mother’ would seem to be an inexorable fate.

Maria is one of Thomasine Gyllembourg’s most singular stories. It deviates considerably from the conventional everyday story, both in its complex, well-structured narrative and in its lack of any actual edification. By illuminating Maria’s psyche, Thomasine Gyllembourg challenges her own – and her contemporaries’ – Romantic notion of woman as a consummate, lovely work of art.

“Through the wrought-iron fencing surrounding the churchyard, they saw the tall, snow-white marble cross shining like a mirage in the rays of the rising moon […] On the wide base sat Maria, she was leaning against the cross, her hands lay folded in her lap, her lovely face looked up to the heavens, the moon was reflected in her translucent eyes, and in its pale light she looked even paler than her usual self.”

Maria’s traumatically fixated mind determines her gradual transformation from life-giving to doomed and suffering mother. The suffering Maria at the foot of the cross maintains the idealisation of woman; she is the ethereal, semi-transparent, and transfigured woman who, in rising above the body and the vexations of mortal life, betokens a higher ideality. Maria is also seen as a mad woman: “Alas, Maria! your sorrow, your lonely withdrawal into yourself, has made your soul ill and obscured its clear gaze.” She is caught up in the self-devouring logic of desire which she is compelled to follow, notwithstanding that by doing so she sacrifices woman’s highest calling – to make others happy. She lets Adolf down, and when he dies of this disappointment she also disappoints the children – only to obey the inner voice that commands her to insist on her own traumas, her own story.

In this sense, Maria primarily deals with the dichotomy and madness that the experience left in the woman who wanted to ‘love romantically’ – meaning, with both body and soul and in defiance of all considerations. The ‘downside’ of being the ‘exception to the rule’ is here revealed.

Woman as Artist

Gabriele in Extremerne (1835; The Extremes) would also seem to half belong in the world of art and eternity: “Gabriele stood like a marble pillar, silent and pale, and only her violent trembling betrayed that she was alive.” Her death-like condition is, on the surface, the result of a clash between her choleric, proudly aristocratic father and a pushy commoner, who sees it as his principal duty to bait the elderly Count. Fundamentally, however, Gabriele’s “trembling” is linked to the suppressions and prejudices that prevent her from being united with Hermes.

Far into the story, Gabriele has some mystery about her which both fascinates and alarms Hermes. She initially appears to him as an “airy being”, “the fleeting nymph”, and it transpires that she is reluctant to admit that she is actually the daughter of a Count, and also that she is concealing yet another secret: not only does she look like a work of art, she also creates art. In all secrecy, she paints delicate miniatures, which her uncle – the free-as-a-bird artist – converts into hard cash for her. But, that is not all: she uses her earnings to maintain her father’s opulent lifestyle, which he considers to be one of the privileges of the aristocracy – while, at the same time, his sense of honour is affronted by his daughter having to sully herself in order to earn a living! It is, therefore, hardly surprising that Gabriele is something of an enigma to Hermes – in all her “fleeting” form she has to cover many a paradox.

In the person of Gabriele, Thomasine Gyllembourg touches on her own problem as an artist. She, too, created her everyday stories in secret. Anonymity was partly to spare her personal reputation – she had already been the talk of the town once too often – and partly to prevent a direct identification between the fictional material and its author. But it also served to remove the obstruction that the female gender in itself placed in the way of artistic accomplishment.

“[T]hese unfortunate, fatherless stories,” wrote Thomasine Gyllembourg in a letter to her daughter-in-law, referring to the everyday tales.

In the well-read circles of Copenhagen, conjecture was rife as to the pen behind the ‘everyday stories’. And Thomasine Gyllembourg energetically joined in the guessing game when the opportunity arose – so much the better to cover up the truth. When writing to her daughter-in-law that “I sigh and sigh again”, she is undoubtedly doing so with ill-concealed coyness:

“Do you know who Prof. David alleges to be the mother of these unfortunate, fatherless stories? You! what do you say to that? He is convinced, he says, that they are made at home in our house; by Ludvig and you, perhaps also something by me. Is that not agreeable? Woe betide me, poor me! It truly disheartens me. To be in company with you is certainly a comfort, though! But… But. I sigh and sigh again!”

(Letter dated 8 August 1833).

And in this complaint there lies a deep truth about gender and art. In her view, and in that of her contemporaries, woman fulfilled her highest purpose by being a mother and by being guarantor for that which was beautiful in life – by being like a work of art. To create great art, however, you had to be a man. Thomasine Gyllembourg’s stories were therefore “unfortunate”, illegitimate everyday stories – equivalent to Gabriele’s miniatures.

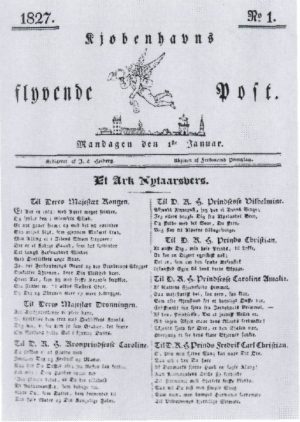

There are other similarities between Gabriele’s and Thomasine Gyllembourg’s projects. Both create applied art: Gabriele’s little paintings are mounted in boxes, furniture and jewellery, while the everyday stories “divert” and instruct. Thomasine Gyllembourg also, in a sense, makes a living as a professional artist. Right from the beginning in 1827, when her first story was published in her son’s brand new periodical Kjøbenhavns flyvende Post (Copenhagen Flying Mail), the added financial bonus from her writing was of not inconsiderable significance in the always precarious joint economy of the household.

“It was New Year’s day 1827. From that day onward, every Friday afternoon I crept down to the gateway and took care to bar the delivery boy’s way up the stairs. There were specific orders that the journal should be taken in to father as soon as it arrived. But I circumvented this order by reading it before it came through the door. So it was on Bryggergaardens Trapper [the steps in Brewer’s Yard] that I made my first acquaintance with Mrs Gyllembourg’s stories, which on the 12th of January 1827 made their entry into the world of reading with the lieutenant’s letter to the editor of the Flying Mail.”

Benedicte Arnesen-Kall: Livserindringer 1813-1857 (Memoirs of a Life 1813-1857, published 1889).

“Busy, busy I must be,” she entreated in 1833, having submitted a written account of “the state of our funds” to her son and daughter-in-law – and it was not exactly good: “poor as a church mouse” was the conclusion reached at the end of a lengthy report. That same year saw the first publication in book form of Noveller, gamle og nye af Forfatteren til En Hverdags-Historie (Stories Old and New by the Author of An Everyday Story) – and the publication earned a fee. Up until 1845, when Thomasine Gyllembourg brought her literary activities to a close, she published on average one book a year; so she did keep busy!

Hereafter, however, any resemblance to Extremerne’s female artists comes to an end. The everyday stories were more than causeries and bread-and-butter for Thomasine Gyllembourg. On a number of occasions she declared – always anonymously – that for her, art was virtually a personal prerequisite of life. It was a never uncomplicated occupation, but one she nevertheless undertook because she so wished.

In 1834 she risked defending her anonymity publicly. She made up an exchange of letters with a Mr Celestinus who most urgently requests the writer to cast aside the mask of anonymity as he is unable to convince his family and his fiancée that he is not the author of the stories. Thomasine Gyllembourg replies that his demand “is to me the same as demanding that I never again put pen to paper, and you really cannot know if this would not cause me just as much suffering as the loss of your sweetheart would cause you.” She could indeed employ a caustic pen when shielding her secret.

It is by upholding this tension between male, expansive creative power and female, vegetative ‘being’ that Thomasine Gyllembourg manages to go into and out of her era at one and the same time. In all her “meticulousness” she presents an interpretation of life that would not reveal its inner contradictions until the Modern Breakthrough of the 1870s.

She went further, however, in revealing the nature of the writing process itself:

“The author’s reward during the work itself has thus been that of forgetting one’s own individuality combined with the greatest awareness of one’s own being, this is the gratification which the author of An Everyday Story has wished to provide for others through the simple tales.”

Translated by Gaye Kynoch