“What does an actor leave of that which has vibrated in his inner being? Who is able to keep hold of this? It is as impossible as holding onto a tone or the fragrance of a flower. Although Goethe lets Zeus tell the Beauty who is complaining that it is but transitory: ‘I only gave beauty to that which is ephemeral’.”

It was a feeling of sorrow and hopelessness that led the actress Johanne Luise Heiberg (1812-1890) to start writing her memoirs in 1855, at the age of forty-two: Et Liv gjenoplevet i Erindringen (1891-92; A Life Relived in Memory). The most highly-acclaimed Danish actress of the Romantic Age, she had become a myth in her own lifetime. But the demand for greater realism on stage gradually began to signal a new era with different ideals and the expectation of different aesthetic values than those she and the whole ‘house of Heiberg’ stood for.

The writing process was undoubtedly an often painful form of self-therapy for Johanne Luise Heiberg, a way of looking at her life that could serve as clarification of the disquiet and discomfort that, in spite of all her success, remained a discordant ambience in her life. Nor was the main aim of her memoirs to relive the actual past, it was more a case of finding some context that could explain the no w, the point from which Johanne Luise looked back as she wrote. The intention of her memoirs was not solely to explain and illuminate the split in the self, the other, the foreign, but also the genius Johanne Luise. Et Liv gjenoplevet i Erindringen is a description of a life seen through sharply selective eyes. She strikes a pose in order to glorify and preserve – and also to understand – that which had been, her own ephemeral art.

In 1917 Georg Brandes wrote of Johanne Luise Heiberg’s memoirs:

“I confess that for me personally all this is not worth a bean. It is of some little psychological interest and for many of a somewhat greater curiosity interest; but otherwise it is unreadable and vacant. As an actress Mrs Heiberg was a swan, as a person a goose, and in her literary products the goose-like is all the more apparent because adulation had made her just as conceited as she was ignorant and – outside the art of acting – deficient in intelligence.”

Liv og Kunst (1929; Life and Art: articles published 1914-27).

In her four-volume memoirs, the desire for clarification also becomes a construal in words, highlighting and illuminating those parts of the personal story needed to create the lasting monument to her life and art. The way in which the script freezes the ephemeral paradoxically becomes a way in which she is able to escape death. Johanne Luise Heiberg did not want Et Liv gjenoplevet i Erindringen to be published until after her death. Thus she could write more freely, given that she could stand outside and look at herself as someone “deceased, whose life was over, and who had nothing to do with the still living personality who guided my pen”.

Spontaneity in the writing process was, however, as with everything else in Johanne Luise Heiberg’s life, kept on a tight rein. She surrounded herself with a whole parade of advisers who were to help her with the editing, and who in fact cracked down heavily on the most controversial passages. The memoirs that were published from 1891 to 1892 therefore presented a polished version of her temperament. Nevertheless, readers reacted vehemently to her fictionalisation of events. But for readers today, it is these handlings of the truth that reveal the ambiguous personality in which the passionate and demonic go hand in hand with the sensitive and sincere. In the stage-management of her written account, she also remains, in the Romantic sense, an ‘interesting’ figure.

The Romantic concept of the ‘interesting’ denoted, among other things, the aesthetic fascination with the hidden, the unspoken, the complex, and the corporeal. Johanne Luise Heiberg’s use of ambiguity, both on stage and in the way in which her memoirs mask the actual nature of events, can be seen as a metaphor for the seductive allure of that which is ‘interesting’.

Mistress Pätges Becomes Mrs Heiberg

To the nineteenth-century Danish bourgeoisie, Johanne Luise Heiberg was the very apotheosis of womanhood and cultivation. Her own social origins were, however, quite different. In her memoirs, she paints a picture of little Johanne Luise Pätges as a girl whose free and delicate nature soon led to a feeling of ‘otherness’ and loneliness within the humble and disharmonious household swarming with children. Unhappy family life was further aggravated by the sexual vulnerability she felt once her talent for dancing had been spotted. Puberty was thus an anxious and worrying time for her.

As safeguard against an often harsh reality, during childhood Johanne Luise Heiberg developed a belief in the world of fantasy in the form of small elves who protected her. The elves gave her a sense of personal potency and a connection with nature, which also applied to her acting:

“In the performance of my roles, I firmly believed that elves aided me, ‘for,’ I said to myself, ‘I have never learnt this art after all; how, then, should I know how to do it by my own efforts?’”

Throughout her life, it was therefore important to her that she could set the limits of the accessibility which could be part and parcel of being on public display in the theatre. This particular talent for self-delimitation was refined to perfection after she moved into Thomasine Gyllembourg’s home in 1830, at the age of seventeen. In 1831 she exchanged, as it were, her disharmonious family for a small, intimate, harmonious family by marrying Thomasine Gyllembourg’s son, philosopher and writer Johan Ludvig Heiberg. She was eighteen, he was thirty-nine. The strong ties between Johan Ludvig Heiberg and his mother meant that Thomasine Gyllembourg moved into the newlyweds’ home, where she remained until her death twenty-five years later. Like her son, Thomasine was captivated by Johanne Luise, and the two women developed a close friendship. The trio was not, however, quite as harmonious as the chocolate box picture presented to the outside world, the image that raised the Heiberg home to the status of a temple of good taste. The close ties between mother and son, with their slightly erotic tinge, gave rise to difficulties. Below the shiny surface of the tasteful home there was an undercurrent of incestuous complications. They remained, however, at the level of intimation, held in an iron grip of well-bred cultivation.

In 1858 Johanne Luise Heiberg, under the pseudonym “Oculus”, wrote an article “Tag ikke i huset hos dine børn” (Do not Move in with your Children), in which she flags the consequences for the young newlywed woman of living under the same roof as her mother-in-law. In her memoirs, these general deliberations are put in more concrete terms:

“What she [Thomasine Gyllembourg, ed.] was less disposed to allow, was that she thought I seemed to receive too much of her son’s love, exclusive possession of which she had for many years been accustomed to, and this often caused her bitterness both against him and me.”

The intuitive cultivation of which Johanne Luise was seemingly in possession at the time of her marriage was, in Heiberg’s distinguished hands, honed and made complete. He created “Fru Heiberg” (Mrs Heiberg) the myth, and he maintained the myth by distancing her from the outside world; at first, his young wife felt this to be a restraint. Heiberg was a Pygmalion figure who put his theories into practice through his wife. Had he not taken a methodical approach to the refinement of her talent, she might not have reached the heights on the cultural stage that she did. But she was not merely malleable putty in his hands, as her memoirs in themselves testify. The ‘putty’ fought back and became creative in her own right. Gradually, however, she took on Johan Ludvig’s views as her own, implementing one particular principle with perfect precision: “Fru Heiberg” should be seen, but only at a distance. By drawing a clear line between the artist and the private individual, she could maintain the image of the ideal figure to whom most people only had access when she was on stage. Maintenance of this distance also had an extra bonus in that it gave her the opportunity to perform on two stages: the public one at the Royal Theatre and the private one at home where, for the few initiated, she could appear as the embodiment of domestic – but at the same time aesthetic – bourgeois womanhood. On the theatre stage, the sight of her was the focal point, whereas the domestic stage was more focused on her being – her ability, in an airy and almost translucent way, to project something sublimely spiritual.

To counter the accessibility that Søren Kierkegaard described as “this inhumanity that causes so much unfairness, yes, cruelty to women dedicated to the service of art […]”, Johanne Luise Heiberg worked out clear and often rigid precautions. She writes in her memoirs: “Actors are therefore better off if they live a kind of incognito life outside the theatre and mix as little as possible with the crowd. Much of the fascination of the stage fades when everyone can associate with them in their private lives, stroll up and down the streets with them, and carry on all the everyday chat that sullies every personality. It is best that they stand before the general public in the ideal lighting behind the row of lanterns.”

There was a special form of negotiation between Johanne Luise Heiberg and the learned men who gathered in the Heiberg home for what they in fun called “læseballer” (reading balls). When aesthetics and philosophy were discussed, her intuition and empathy indirectly corroborated the male knowledge, and thereby also the validity of the theories. After Heiberg’s death, this negotiation continued in the form of an intensive correspondence between Johanne Luise Heiberg and, among others, theologian H. L. Martensen and politician A. F. Krieger.

Just about every nineteenth-century male cultural figure in Denmark – indeed, in Scandinavia – had some kind of take on Johanne Luise Heiberg. Kierkegaard analysed her as an actress; Hans Christian Andersen, Adam Oehlenschläger, and others wrote roles and poems for and to her; Henrik Ibsen wrote his famous rhymed epistle to her, and Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson even gave her a role among the fictive characters in his short story “Absalons Haar” (1894; Absalom’s Hair). By rendering her part of the fiction, he highlights her status as a myth that can cross the line between reality and fantasy.

In his short story “Absalons Haar” (1894; Absalom’s Hair), Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson paints this portrait of Johanne Luise Heiberg:

“One of the most remarkable women in Scandinavia, […] Johanne Luise Hejberg, once saw Helene when she had but just attained to womanhood. She could not take her eyes off her; she never tired of watching her and listening to her. Did the aged woman, then at the close of her life, recognise anything of her own youth in the girl? Outwardly too they resembled each other. Helene was dark, as Fru Hejberg had been; was about the same height, with the same figure, but stronger; had a large mouth, large grey eyes like hers, into which the same roguish look would start. But the greatest likeness was to be found in their natures: in Fru Hejberg’s expression when she was quiet and serious; in a certain motherliness which was the salient feature in her nature.”

This interplay between writers and actors was of major significance for Johanne Luise Heiberg. It gave her the occasion to put words and movements to her own passionate emotions which, albeit within the remit laid down by the writers, gave her the opportunity to create a strongly subjective art form. There was a common denominator between the light vaudeville roles, which Johan Ludvig Heiberg wrote for her, and the more demonic roles in Oehlenschläger’s and Hertz’s plays: she had to keep her artistic interpretation within the parameters of the beautiful illusion; her presentation had to be in accordance with Heiberg’s insistence on the true, the good, and the beautiful.

Language of the Body

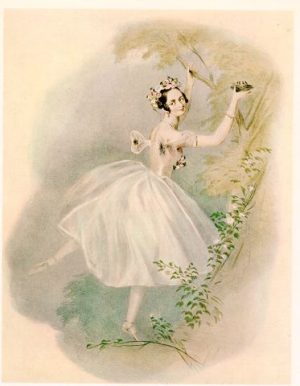

The requirement of a physically beautiful interpretation of the texts met with sympathy in Johanne Luise’s own clear ideas about, and exceptional talent for, the physical aspect of acting. The upholding of the ideal in the transient stage pictures could, in her opinion, be given more substance by the use of the ‘plastic’. ‘Plastic’ is chiefly a term applied to art forms requiring moulding, but Romanticism also used it as an expression of beautiful physical movement and posture, bearing a resemblance to sculptures. Johanne Luise Heiberg’s first experience of the Royal Danish Theatre was as a pupil at its ballet school. Here, she had received basic training in the classical plastic art, which she would later employ to great effect as a means of expression. The elasticity of the body and ability to assume beautiful postures were mainstays of her art. The technical ability to execute these movements was undoubtedly a prerequisite, but Johanne Luise Heiberg stresses that this must be contained so that the ‘plastic’ could become part of the inner reality of the actors. The postures were not to be rehearsed “in a mirror”, but had to be “felt inwardly” so that the audience’s imagination and delight could be uplifted by the “beautiful illusion” shown on stage.

In her memoirs, Johanne Luise Heiberg gives a detailed account of the significance of the ‘plastic’ for the art of acting. The gaze by means of which the movements of the body will be fashioned should, she stresses, be an inner, not an outer, self-reflection:

“How can I, in a mirror, study modesty when it is the lowering of the gaze to the ground that gives precisely the right expression? How can I express pain in my countenance – which is essentially achieved by the upward gaze of the eyes, because the brows instinctively draw together – when I am meant to be staring straight at the mirror? […] I see my own postures, because I feel them, but in order to feel them the mind and eye must be untethered and not forced to turn towards a specific point.”

The role model for this physical expression was the ideal of beauty in Antiquity, when the revealing nature of garments meant that the body attracted far more attention than that allowed by the restraining corsets of her day, and when the “eye”, according to Johanne Luise Heiberg, required the body to move in harmony with the “beautiful, flowing raiment”. When acting a role at the theatre, she was able to combine the Romantic requirement of genuineness and naturalness with a more monumental representation. In so doing, she bound the passion in a form so firm that no passions, however fervent, could run away in ungainly overstatement. The slow and ceremonious movements, which we can try to reconstruct following Johanne Luise Heiberg’s directions in Et Liv gjenoplevet i Erindringen, constantly call attention to themselves as art, and certainly not as reality in the sense later exacted by naturalism. Johanne Luise Heiberg was thus also pointing to herself as a work of art – not in the sense of a passive object of art, but as an active point of condensation for the writers’ ideals and visions. In the beautiful postures she gave the texts body and soul. At the same time, behind the seductive power of the “veil of beauty”, she could give intense expression of her own passion and yearning.

Her avid showdown with naturalism should be understood against this backdrop, and should be seen as a defence of an art that held the potential to play with eroticism and dreams without breaching the boundaries of propriety. These were opportunities, she felt, taken away by naturalism, because the insistence of a more “bare” naturalistic staging on “raw reality” would give a far too unveiled and brutal picture of the passions. And that was something she, as spokeswoman for beauty, could not tolerate.

Paradoxically, Johanne Luise Heiberg herself pre-empted a significant factor of naturalism: psychological analysis. She worked intensely with the psychological aspects of her characters and used this knowledge in her performance; this became her ‘method’ of acting. The distinction from naturalism was in the aesthetic presentation itself. She wanted to preserve the theatrical in theatre, thereby to preserve the distance that had become vital to her art and to her self-respect as an actress.

Her memoirs repeatedly give a picture of how she, seduced by the illusion, becomes so abandoned in a role that she quite forgets her own self. Behind the masks of the drama, she finds an outlet for the passion she must so sharply delimit in her real life. And the romantic roles not only gave her the scope to explore her own eroticism; in the so-called trouser roles she also had the opportunity to familiarise herself with a male eroticism.

The melancholy so clearly expressed by Johanne Luise Heiberg in her memoirs, the never-fulfilled yearning, is manifest in naturalism’s creative female souls as a desperation and depression, which was often too much to live with – to outlive – as was the case for Victoria Benedictsson, Adda Ravnkilde, and others. For Johanne Luise Heiberg, on the other hand, the formal aesthetic was not solely a restriction, but also an opportunity, a safe place where the demons could both play and be kept in check. Theatre work became, she wrote, like a lightning rod, diverting the desires of the turbulent mind.

Acting and Gender

Johanne Luise Heiberg pondered at length, especially in her later years, the moral legitimacy of acting. These deliberations were guided by a deepening religiousness, but they also clearly manifest her ideas about the relationship between art and gender. This she expresses more than plainly in her memoirs: the act of putting oneself on display and being adored can have catastrophic consequences for the man because it is not part of his nature, like it is for the woman.

In this respect, Johanne Luise Heiberg’s view is in line with that of the French feminist Simone de Beauvoir.

Actresses, says Beauvoir, have their femininity corroborated through their art:

“Their great advantage is that their professional successes – like those of men – contribute to their sexual valuation; in their self-realization, their validation of themselves as human beings, they find self-fulfilment as women.”

A great actress must, however, according to Beauvoir: “go beyond the given by the way she expresses it; she will be truly an artist, a creator, who gives meaning to her life by lending meaning to the world.”

There was a good reason for Johanne Luise Heiberg’s concern about the moral legitimacy of an acting career for women. When old P. A. Heiberg, in exile in Paris, received the news of his son’s marriage to a very young actress, his first reaction was that of course she must give up the theatre. “An actress,” he writes to his son, “is like a lady-in-waiting, both are a kind of servant, that one to an audience, this one to her exalted masters.”

In her memoirs, Johanne Luise Heiberg gives this description of the gender-specific nature of acting:

“I have said that the acting profession is more hazardous for the man than for the woman; for there is nothing unnatural to a woman in being applauded, loved, worshipped, or being celebrated by poets; on the contrary, this has been considered the woman’s right from time immemorial […] and none of this need take away any of her natural femininity. But when this same befalls a man, then his disposition is disturbed; for to him there is something unnatural herein, and the consequence does not fail to appear. When a man becomes the object of common adoration, as if he were a woman […] then, little by little, consequences of a highly contrariwise bearing emerge; he loses his masculinity and becomes a vain, hollow, ridiculous, wretched cross between man and woman; he is distorted for life.”

Being a public celebrity, Johanne Luise Heiberg was constantly in danger of being accessible in a sexually implicated manner, even when she was not actually present. In an article about Johanne Luise Heiberg, “Krisen og en Krise i en Skuespillerindes Liv” (1848; The Crisis and a Crisis in the Life of an Actress), Kierkegaard describes the situation thus: “[…] her portrait will be painted for every art exhibition; she will be lithographed, and should fortune treat her very favourably her portrait will even be mounted on pocket handkerchiefs and hat crowns. And she who, being a woman, takes particular care of her name – being a woman she knows that her name is on everyone’s lips, even when they wipe their mouths with the handkerchief.”

Kierkegaard’s article was written in connection with a debate about Johanne Luise Heiberg, now in her thirties, still performing the role of Juliet in Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, a role she had first taken on in her young days. Real female art is first achieved, in Kierkegaard’s opinion, when the woman has the power of “metamorphosis”, the ability to transform herself, and this first occurs in the fullness of time when she is over her “accidental youthfulness”, which is ‘self-sufficient’.

Kierkegaard’s article gives a picture of Romantic notions of the woman’s special significance as an agency for the ideal. As we can understand from Johanne Luise Heiberg’s memoirs, however, this capacity for transformation in order to facilitate manifestation of the ideals also involves being locked in a form of femininity that exacted great suffering and rigid demarcation of self.

Women’s Emancipation

Throughout her life, Johanne Luise Heiberg had an ambivalent relationship to other women, and in particular to female artists from whatever field, or to so-called emancipated women. This antipathy can perhaps seem paradoxical, given that she lived under the same roof as one of the most productive female writers of the day, her mother-in-law Thomasine Gyllembourg, and also that she herself wrote articles and vaudevilles: for example, En Søndag på Amager (1848; A Sunday on Amager); Abekatten (1849; The Monkey); and a book about her parents-in-law, Peter Andreas Heiberg og Thomasine Gyllembourg. En Beretning støttet på efterladte Breve (1882; Peter Andreas Heiberg and Thomasine Gyllembourg. An Account, Supported by Surviving Letters).

In most of Europe, actresses were regarded as muses of the theatre, but they were not welcome in polite society. They were compared with other women in the public domain: the prostitutes and courtesans. It was therefore of crucial importance to Johanne Luise Heiberg that she should highlight the other side of her life: the housewife. It was her goal, on top of her theatre work, to execute the domestic duties and beautification of the home on an equal footing with other housewives, and it was therefore a triumph when she heard: “[…] visitors, foreigners and Danes alike, say that seeing me in my home, it was impossible to believe that the lady of the house was an actress.”

In 1851 she wrote a vicious article, “Qvinde-Emancipation” (Women’s Emancipation), which was, however, never published. The direct cause of her ire was undoubtedly the notorious “infatuation” between Mathilde Fibiger and Johan Ludvig Heiberg, which blossomed in connection with his support of her book, highly controversial at the time, Clara Raphael. Tolv Breve (1851; Clara Raphael. Twelve Letters), published under the pseudonym “Clara Raphael”. Johanne Luise did not mince her words. Her argumentation against these “the women of recent times possessed by witches” is that their desire to transcend women’s circumstances, their longing to live for the “elevated and the beautiful”, transpires at the expense of their most important duty as “gardener of domestic life”: “Should you enter the room of such a lady, you can be quite certain to find everything in the most disagreeable disorder,” she writes.

In an article published in 1859, “Om Husvæsenet og Pigebørns Opdragelse (fra en Dame til den, hvorpaa det passer)” (On Management of a Household and the Upbringing of Girls (from a lady to whom it may apply)), written under the pseudonym “Spectatrix”, Johanne Luise Heiberg criticises Copenhagen mothers for sending their daughters to what were known as “Pigeinstitutter” (educational institutions for girls). The article is not only a manifestation of opposition to the “for the lady unnecessary imbibing of old learning”, turning the girls into “little soldiers in the female emancipation regiment”; it is also a warning that the young girls will have to “march past for their [men’s] profane inspection” on the way to and from school. This accessibility to the male gaze would break the young girl or turn her into “a coquettish vanity-fiend”. The male gaze’s profanation of the virginal young girls is thus equated with the way in which male scholarship has spoiled unsophisticated and pure girlishness.

The passion with which Johanne Luise Heiberg here cuts off new opportunities for womankind would seem to be in sharp contrast with the empathy she presented in her art. Her rage was undoubtedly attributable to the new demands being made by Mathilde Fibiger and others – the demand to be themselves and not, as Johanne Luise Heiberg would have it in “Qvinde-Emancipation”: “We ladies should be like the Chorus in Greek tragedy, the gentle, steady, guiding, reconciling principle; and not those who bring more trouble to the troubled.”

Translated by Gaye Kynoch