On the title-page engraving of the 1681 edition of her hymnal Siælens Sang–Offer (Song Offering of the Soul), the first “She-Poet in the Lands of the Hereditary King”, Dorothe Engelbretsdatter, was shown for what she was: a clergyman’s widow who wrote. Pensive, and with an eye on her memento mori, the skull and hourglass, she is writing her own hymnal.

The picture is unusual – as was Engelbretsdatter herself. The writing woman is an exception in seventeenth-century literature, and she must, like Engelbretsdatter, use intellect and emotions alike to make her work acceptable to herself and her contemporaries. The title-page engraving discloses none of the troubles encountered by the woman who wrote. The woman in the picture is writing with assurance, concentration and as a matter of course. Despite the effortlessness with which the situation is portrayed, the picture is actually unique of its kind: the depiction of a seventeenth-century Nordic woman working on her book.

Dorothe Engelbretsdatter wrote of herself and her hymnal:

From sanctimonious hypocrisy

Prayer has freed me

In you was my joy

Your Word in this life

Was my chosen pastime

In my widowhood.

The eighteenth century can exhibit many pictures of women who, directly and in particular indirectly, are occupied with their own literary creation, and the stage-management of the creative woman in these portraits has been very carefully thought through and is sometimes extremely detailed.

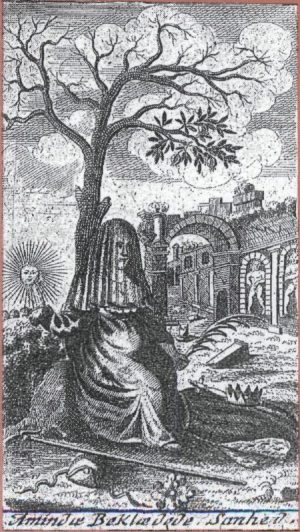

An early eighteenth-century author, Anna Margrethe Lasson, is presented on the title-page engraving of her novel Den Beklædte Sandhed (1723; The Truth in Disguise) in quite a different way than Engelbretsdatter the clergyman’s widow. Veiled, Lasson sits in an allegory of her own fable. In one hand she is holding the sun, the symbol of enlightenment; in the other hand she is holding a palm branch, the symbol of victory. At her feet lie the shepherd’s crook, a royal crown and a cape: props in her “little novel”. Lasson is not wielding the pen, she is showing the tale. She is the passionate lover of the Danish language, the veiled Aminda. This picture of Aminda indicates the degree of carefully prepared stage-management the new eighteenth-century secular literature required of its practitioners.

In the eighteenth century, ceremonious and learned forms of seventeenth-century expression were replaced by a more unrestrained and colourful setting. Literature in the eighteenth century was penned not only by authors and writers whose religious calling, royal status, or royal connections gave them access to the sphere of books, but also by writers of sufficient learning, wealth, virtue, or faith in God to be able to stage-manage themselves and equip themselves with the intellectual attire appropriate to their preferred genres. It was not merely inclination and whim that motivated writers and authors in the eighteenth century to scribble away on their plays, diaries, didactic poems, tragedies, hymns and moral tales. Every text and approach to literature’s new general readership was a ‘truth in disguise’; the ‘disguise’, the writer’s mask and stage-management, was a signal of the text, its possibilities, space and parameters. The mask was – as at the popular and contentious masked balls – both entrance card and sophisticated statement of potential. And while the writers displayed their masks on the literary Parnassus, the masked balls in the royal courts of Denmark and Sweden were the stage for violent showdowns in the power struggle between bourgeoisie and aristocracy. The magic of the mask was not an exclusively literary matter.

In the didactic and satirical literature of the 1700s, it became popular for male writers to disguise themselves as women.

By thy mask I shall know thee – we could join Karen Blixen and say this of the many eighteenth-century writers who were particularly reflective and self-aware in their approach to the written word.

The mask theme often plays a key role in Danish plays written by women. The false suitors are ‘painted’ and mendacious, whereas the virtuous and tender heroines and their intimate friends are open and honest. The mask or disguise can, however, prove an important means by which to escape the painted and deceitful villains. “My fair sex! Beware, / Employ the mask at its proper time and place, / When your heart is in danger,” we are advised in Anna Catharina von Passow’s pastoral play Elskovs eller Kierligheds–Feyl (1757; Passion, or, The Problem with Love).

The eighteenth-century literature written by women displays various construals of the female role. The women create and appear in masks and costumes that give them artistic opportunities for development, and which also render them recognisable as writers. The well-read and sensible woman is related to the seventeenth-century learned women. The seventeenth-century debate on learned women often stresses that woman is possessed of common sense and as such will be able to assimilate the men’s learned culture.

Why should not the noble female sex

Be as consummate

In learning, quick of wit and beautiful

As the man, and study.

God and nature too

Have made it so that she

With sound mind

And senses is endowed.

Thus writes the academic verse artist Anders Bording in his long poem Scutum Gynæcosophias eller lærde Quinders Forsvar (Scutum Gynæcosophias or in Defence of Learned Women) from the mid seventeenth century. The eighteenth-century discussion of women’s rational abilities primarily sees women as contributors and as an audience for a new literature written in the national language, including a popularised scholarly literature. And thus in his work Forsøg til en Fruentimmer–Philosophie (1749; An Essay on Philosophy for Woman), the young philosopher Friederich Christian Eilschov uses the example of a sensible woman in his attack on the outdated culture of Latin scholarship.

The Norwegian poet Christian Braunmann Tullin composed an ambitious wedding poem for a Norwegian merchant in the form of a deputation of women contesting the supposedly natural law of male supremacy. In his “Indlæg til Fornuftens Ret fra Qvindekønnet” (1758; Contribution towards a Law of Reason on Behalf of the Female Sex), we read:

Our sex must by now have sighed for long enough in enforced chains; and, as a silent, patient flock, bowed down before the villains.

The woman writer with the possibility to create an image of herself as well-read and rational is employing a signal that is comprehensible and topical in the eighteenth-century discussion of women’s intellect and the widespread defence of women’s rational abilities. Inspired by the rationalistic theory of mind, which makes no distinction between men’s and women’s minds and thereby their potential for rationality, Holberg energetically includes intelligent and sensible women in his writing, and in the 1728 edition of his Introduction til Naturens og Folke–Rettens Kundskab (Introduction to the Study of Natural and Human Laws) he stresses that “among women there are splendid mental talents”. At an early point in his writing career, Holberg realises that women are a potential audience for his useful and rational works written in the national language. Holberg meticulously and humourously creates an image of himself as satirist and pragmatic writer. Comical Hans Mickelsen, mayor of Kalundborg, is one of his ambiguous literary masks. In “Zille Hans Dotters Gynaicologia eller Forsvars Skrift for Qvinde-Kiønnet” (1722; Zille Hans’s Daughter’s Defence of Womankind), Holberg masks himself as the virtuous Zille and satirises the custom, the laws and the upbringing that keep womankind in bondage and stupidity. The Zille figure functions as an unambiguous and positive writer’s mask; and, in intelligent Zille, Holberg has created a picture of an audience type: the sensible and knowledge-seeking woman.

“Zille thus becomes a symbolic representative of the female readers Holberg wanted,” writes Anne E. Jensen in Holberg og kvinderne (1984; Holberg and the Women), in which she gives an account of the evolution in Holberg’s view of women.

In her autobiography, Mit ubetydelige Levnets Løb (1787: My Insignificant Life), Charlotta Dorothea Biehl presents herself as an intelligent and well-read woman. The way in which she organises her life story calls to mind Holberg’s portrait of Zille. Holberg’s Zille tells us: “I had barely turned eight years of age,/ I wanted to know more/ than A B C and the Lord’s Prayer/ I had the desire to study.” Parallel to this, Biehl writes of herself:

“Nature had endowed me with a ready aptitude, a strong memory, and an exceedingly great desire to learn all that was possible. Before the age of five I read and understood whichever German and Danish book I was given.”

Biehl’s intimate friend, Lord Chamberlain Johan von Bülow, calls her a “learned lady” and writes that when they met for the first time he was “somewhat afraid to make her acquaintance”. The learned and well-read woman is a recognisable figure, but she also gave rise to disquiet and resistance among the men, and it is characteristic that Biehl refuses to call herself learned. She prefers to highlight her intellect and her ability to comprehend the written word. In Cornelius Høyer’s miniature, painted in c. 1775, she is holding a sheet of closely-written text. She has used her capacity for rationality, she has familiarised herself with the text and can turn her gaze to the beholder.

Women’s advocate Mrs Nordenflycht presented herself as a learned woman in the familiar seventeenth-century tradition and as a modern, rational eighteenth-century woman. She acted the part of intelligent female citizen able to pass comment on matters philosophical, political and literary, and to engage in dialogue with both Holberg and Rousseau. In 1753 Nordenflycht became a key figure in the literary society known as Tankebyggar-Orden (Order of the Thought Builders); in her lyrical poetry she could play the role of a “shepherdess in the North”, creating a forum for a self-aware and heartfelt account of emotions. In Schleffel’s portrait of her, she is elegantly ‘disguised’ with sash, rose and poet’s lyre. In the pastoral story “Fröjas räfst” (1762; The Chastisement of Freja), Nordenflycht uses the poet’s lyre in thought-provoking symbolic self-interpretation. Here it is the male shepherd who is awarded the poet’s lyre as a love-gift.

Stupid law, you blind tradition,

Who bellow forth your craven envy

When you Eve’s sex deny

Access to the Parnassus.

Thus writes Mrs Nordenflycht in the poem “Fruentimbers Plikt at upöfwa deras Vett” (1744; Women’s Duty to Train their Minds).

Nordenflycht considers Newton’s writings to be useful for womankind, and Biehl writes about how she derives profit from her hard-won language skills, whereas Anna Maria Lenngren’s thoughts about education for women take issue with the learned culture and she refers – albeit not without irony – to her “nature and the limitations of my sex”. Inspired by Rousseau, Lenngren problematises the well-read and learned woman. She considers study of the world to be more important for women than the study of scholarly books.

In her poem “Til Lisette” (1781; To Lisette), Mrs Lenngren writes of the young woman who does not have scholarly “airs”:

You do not loudly disagree,

With those who worship melody,

You’ve never known the fantasy

Of examining everything you thing

Nor pride yourself in artful stutter.

You do not seek celebrity

As noble queen on wisdom’s throne,

You pray that simply you may see,

Without a trace of pedantry

Your friends’ approval and your own.

At the same time, the literary development threw up completely new masks for female writers. Writers for the Danish Fruentimmer–Tidende (Women’s Gazette) presented themselves as a gathering of self-taught women, but for a number of the contributors it was the study of life rather than the study of books that gave them legitimacy as writers. ‘Hofmesterinden’ (the Mistress of the Court), a contributor to nos. 2-3, 1767, thus reported that the society had asked her to write on “women’s yes or no in respect of marriage”, because her rank had given her “lengthy experience” in the mistakes her sex can make in matrimonial matters. ‘The Mistress of the Court’ conducts a sophisticated debate with herself about whether she ought and whether she dare feature as a writer at all.

“[…] and an old Mistress of the Court like me, what taste has she? What does such a one know of the new things? What can she tell us beyond what was known before the Flood? Oh what course am I embarking on! I who envisage that both my style, my manner of discourse, indeed the discourse itself, will displease.

“Yet to what can conceit not tempt a woman? The learned title of authoress, the flattering hope that it might perhaps please some, already tantalises me so strongly that I must be hissed from the stage before I sully this grand title.”

Women’s anxiousness to please is a familiar cliché in the early periodical literature, and even though the reader is meant to take the ‘Mistress of the Court’s advice seriously, her ‘mask’ also has its humorous touch. Perhaps the contribution from the ‘Mistress of the Court’ was actually the work of a male rather than a female writer.

Whatever the case, however, it is an exciting and new development that allows life experience to validate a writer. In the second half of the eighteenth century, the experienced woman often features in periodicals, in the moral and sensitive stories, in portrait poems and occasional poems. The experienced female mask is not solely the province of women writers. She also features as narrator in the men’s prose. Thus, in his short story “Børnekopperne” (1805; Smallpox), Knud Lyhne Rahbek gives the word to a worthy townswoman telling her life story to a gathering of cultured friends with an interest in literature.

While the mask of the well-read and intelligent female requires erudition of its wearer, the mask of the writer experienced in life allows its wearer freer reins, or, more accurately, different restrictions vis-à-vis the literary public. As writer and narrator, the woman with life experience is primarily an aristocratic lady dishing out from the pot of virtue and good sense with which life as daughter, wife and mother has equipped her. The new image of the female writer becomes hugely significant and vigorous. The Norwegian “Moer Koren” (Mother Koren), Christiane Koren, for example, bases her writing on her life as a mother. Being the mother of the household, she has honed her powers of perception and her knowledge of human nature. A later nineteenth-century author, Thomasine Gyllembourg, turns all her writing on life experience, and indirectly formulates the contrast between two types of writer: the woman with life experience and the well-read female. Gyllembourg calls her everyday stories “Frugter af Livet, ikke af Lærdom og dybe Studier” (the fruits of life, not of learning and deep studies).

While a growing body of stories in magazines during the eighteenth century rendered the experienced, virtuous woman a standard and sometimes caricatured figure, a quite different category of experience was also generating women writers. The eighteenth-century Protestant movement of Herrnhutism exacted confessional autobiographies of its believers. Herrnhuters enjoined, in principle, all believers to write autobiographies of their religious life, sin, doubt and personal spiritual experience of Jesus. These autobiographies were read aloud in the Herrnhutic communities, and they were exchanged between communities. In telling their life stories, women and men from widely different backgrounds created a confessional form of prose. Investigation of the Swedish Herrnhutic material, in particular, has unearthed fascinating autobiographies written by women.

Pre-Romantic and Romantic literature’s spotlight on the male author as a sensitive self and as a sensing genius can be traced back to the Pietists’ and Herrnhuters’ cultivation of emotion and the religious drama of the soul. In pre-Romantic and Romantic literature the woman is given a new ‘disguise’. She is viewed primarily as inspirer and elicitor of male genius. The Romantic female disguise shares some features with the seventeenth-century French culture of préciosité. As in the préciosité culture, the tender, platonic friendship between man and woman is idealised. However, the French précieuses were themselves creative artists and passionate lovers of language, whereas the Romantic stage-management of the woman restricts her forums for development to the salon and to the personal and semi-public genres of letter, diary, and autobiography. The French culture of préciosité expressed a radical showdown with the pressure of the institution of marriage and with the ‘Latin’ university culture, and it strived for refinement of language and social conventions.

“The verb aimer (to be fond of, to love) must not be used of everyday things such as melons and sugar, but must be reserved for objects of a noble character. The language reform and language purging undertaken by les précieuses goes so far as to propose doing away with all masculine words, which means the majority of words in the French language!” writes Merete Gerlach-Nielsen in “Om at gøre sig kostbar – bevidsthed og oprør hos preciøserne” (On making oneself precious – awareness and insurrection of les précieuses), Forum for kvindeforskning (Women’s Studies), no. 3, 1987.

The pre-Romantic and Romantic image of the woman is far less radical and far more symbolic. Here the extremely real and fleshy Muses, presented by Bellman in his Rococo universe, must also give way to absent women, thinking Venuses and goddesses of fortune.

The sensitive bard Johannes Ewald creates his ‘I’ in proportion to the loss of the woman, Arendse. This absent and unattainable woman, who cannot disturb the sensitive bard by her physical presence, is called forth in the imagination with effortless ease, and features in the refined and adorned space inhabited by the sensitive words. She is the perceived and yet fictitious flesh and blood; Ewald becomes sensitive and creative in his question: “Did I truly have an Arendse? – Or was it a Dulcinea; conjured up by my imagination alone, because it was in need thereof?”

Jens Baggesen construes his friend Christian Pram’s wife as a Venus Urania, a cerebral un-sensuous goddess of love. His work is imbued with her spirit. “And should the glory of eternity reward/ My song, and were I so fortunate,/ To be revered by the sons of a distant future,/ ’Twould be your spirit, your mind, you they love in me,” writes Baggesen in his ode “Min anden Skabelse” (1785; My Second Making). But in the life beyond poems and odes, Baggesen has difficulty in keeping track of the spiritual and physical passions.

The young Knud Lyhne Rahbek also tries his hand at an inspiring platonic eternal triangle. Rahbek’s construal of his friend Michael Rosing’s wife Johanne as Goethe’s Lotte or Beaumarchais’ Eugenie is a youthful attempt to dramatise his own emotional life. The male ‘I’ is here testing his emotional potential.

“Again today a touch of Lotte! and the day before yesterday too! – your dear Rahbek! Thus you called me? Is this not Lotte’s ‘Lieber Werther!’ – Could it therefore be that you have such perfect likeness to Lotte so as to prepare me for a future perfect likeness to Werther!” ponders Rahbek theatrically in his diary, 30 June 1779, after a visit to the Rosing family. Unlike Werther, however, Rahbek refrained from taking his own life.

A Romantic construal of woman is provided with its forum and its female accomplices in the salons of the late 1700s. The salons have unwritten rules and specific genres for tender and precious bosom friendships. The salons, with their reflections on, and stage-management of, emotions, enable the women to reveal themselves as living beings. The Romantic woman, who to Rahbek and Baggesen was an ethereal vision of the soul brooking little reality, now steps out into her reality.

She has to know her mask, however, and prepare herself for what it may show, and what it must hide. How characteristic it is that Friederike Brun’s daughter, Ida, enraptures the salon guests with her silent eurythmy.

In a birthday poem to Friederike Brun, Baggesen wrote of “the happy mother” and her two daughters, Charlotte and Ida:

Where the ear of the happy mother,

Enchanted by the sight of Lotte,

Could surely hear the song of angels

Listening to Ida’s tune –

Where the two angel-sisters,

The full-grown roses of the valley,

Bloomed on tender stems,

Bud by bud, and children yet.

“Sophienholms Erindring” (1813; Memories of Sophienholm)

How characteristic, too, that Swedish Malla Silfverstolpe feels lonely and unfulfilled in the loving friendships of her salon. It is almost symbolic that there is not a single authenticated portrait of Kamma Rahbek, but only a silhouette, a sensitive mask that conceals her features but gives an idea of her bearing.

Translated by Gaye Kynoch