If I of inborn passion occasionally rhyme

Your fancy can be seen on easels and on walls,

Though art of precious hours deprived us many a time

There is no better way to heed immortal calls,

Let envy frown at us, let death exact its vow,

My pencil and your pen are undeterred somehow.

Om jag af medfödd drifft för ro skull stundom rimar

Ehr böijelse syns klar af Edert målerij,

Fast konsten oss ibland har kostat några timar,

Man kan på bättre wis ei oförgäten bli,

Lät afwund grina til, lät döden Schächtan spänna,

För ingendera skräms Ehr pensel ell’ min penna.

Thus wrote Sophia Elisabet Brenner (1659-1730) in a laudatory poem to Anna Maria Ehrenstrahl who, in 1717, had donated a number of portraits she had painted to Svea Landsret (Swedish High Court of Appeal), an action that inspired the poem. It can be said that here Sweden’s first female author is writing to Sweden’s first female painter, and that the verse introduces us to two early-eighteenth-century Stockholm ladies in their occupational roles. Albeit the lines display a degree of becoming modesty, Mrs Brenner’s poem reveals professional pride. Art is an effective antidote to being forgotten. The downside of renown and ability – envy – has to be endured.

The poem to Anna Maria Ehrenstrahl is actually quite representative of its writer’s overall output; most of her work was in the form of poems for special occasions. She paid tribute to royalty and people of high rank on their weddings and their birthdays, and after victories in battle, and she wrote poems to the bereaved and to the deceased. She did not forget her friends, of course, but the majority of her recipients were higher up the social ladder. Two-thirds of her collected occasional poems were addressed to the uppermost social class; they were the ones it was worth paying your respects to, and we know from her contemporaries that Mrs Brenner’s poems were in demand and valued highly. It was not totally unknown for panegyric poetry to be written in honour of talented intellectual or artistic women of the day, and she also wrote poems on the death of women and children. Of fifty-seven elegies, twenty-four were written to or about women; six of the elegies were written upon the death of a child. Sophia Elisabet Brenner was able to put the somewhat hard-and-fast elegiac form to her own use: she discussed with opponents in the debate about the status of women, and she defended her own views as a writer and as a woman. Sometimes her experience was opportune: the writer of the first Swedish domestic medical handbook on pregnancy and childbirth could hardly have hoped for a better reviewer than Mrs Brenner, who had several children of her own. “I have considerable personal experience,” she wrote in 1697 on the publication of Johan von Horn’s Swänska Jordegumma (Swedish Midwife), and warmly recommended the book:

If I may advise you, we cannot neglect,

To own, each one of us, the Swedish Midwife.

Om jag er råda får, så må vi ej försumma

att äga var och en den Svenska Jordegumma.

“I Must Confess that I Find it Hard to Stop

When Reading a Book that Pleases Me”

So who was she, this Sophia Elisabet Brenner? We know about her childhood and upbringing from her own account, “Kurtze Lebens-Beschreibung”, written when she was sixty years old, and published in 1732 in the posthumous second edition of Poetiske Dikter (Lyric Poems). She was born into a German merchant family in Stockholm and received every encouragement to study. Her desire to learn Latin was awakened in a strange way, she tells us. One of the boys at her school, where she had been sent in order to learn to write German, had great difficulties with his studies; feeling sorry for him, the schoolgirl Brenner learnt all the Latin words by heart – given that she was a girl, no one would suspect her of helping the vulnerable lad. Eventually she was given tuition in Latin too, but it all started by chance, she is quick to point out – possibly for tactical reasons.

In telling her life story, Mrs Brenner wrote of the benefits afforded a girl if she learns Latin:

“Whereas otherwise she has to read so childishly where a word of Latin occurs in German books, and women have to pass over it given that they cannot read it.”

Her proficiency in Latin, which is documented in poems and letters, was later to be the foundation of her distinguished reputation.

Mrs Brenner’s autobiographical writings and poetry reveal her intense thirst for knowledge. The family grew large, despite the early death of most of the fifteen children she bore in wedded life with Elias Brenner. Her husband, who was a painter of miniatures, presumably encouraged and supported her in her desire to study. He procured the books she needed and he urged her to write. Finding enough time for study and poetry was undoubtedly no easy matter; the Brenner household would seem to have been a very hospitable place – in fact, a salon for both literature and painting. Many cultural personalities of the day attended: botanist and linguist Olof Rudbeck, for example, and the authors Johan Runius and Jacob Frese. Foreign guests visiting Stockholm would often make their way to the Brenners, to become acquainted with the famous writer and ask her to sign their friendship albums.

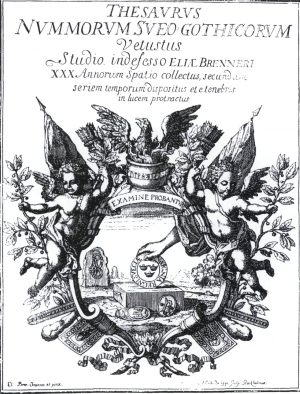

Elias Brenner (1647-1717) came from Finland. A keen archaeologist and distinguished miniaturist, his great passion was numismatics. After his death, Mrs Brenner sold his coin collection and his large book collection.

“The Laurel Wreath Long Used by Learned Men, /

She Gave Once Again to the Women”

Sophia Elisabet Brenner’s circle of friends included the scholarly numismatist Nils Keder and the physician, chemist and author Urban Hiärne, a major cultural figure of Sweden’s period as a great power. Together with Elias Brenner they ‘marketed’ her at home and abroad, sending samples of her work to influential people in the cultural sphere and seeing to it that her reputation as a talented writer spread. Urban Hiärne collected the ensuing panegyric poems – the quotation above is taken from Petrus Hesselius’ poem – and had them published in 1713 as De illustri Sveonum poetria, Sophia Elisabetha Brenner, testimoniorum fasciculus. This “little bundle” of poems includes tributes from Germany and Denmark besides, of course, from Sweden, written both in Latin and the national languages. Distant lands such as Spain, Italy and the Spanish colony of Mexico are also represented. The learned nun, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, who was renowned for her work in “Nueva España” in the late seventeenth century, sent her tribute to an author with whom she was without doubt unfamiliar – “Musa Polare” (the Polar Muse) as she calls her in the poem – in faraway Stockholm. Mrs Brenner herself pays attention to others in similar fashion – for example, the hymn writer Kingo – in hope of reciprocated attention.

Mrs Brenner was also persuaded to publish her poems in print. Urban Hiärne had invited the public to subscribe to the “fair lady’s” poetic writings. Advance purchase would give a discount if half of the five Swedish “Caroliner”, which was the price of the poetry collection, was paid immediately.

“Equally disgraceful sins and equally noble virtues

Are seen from day to day in women and in men”

Once Aurora Königsmarck and her female friends had performed Racine’s play Iphigénie at the court in Wrangelska Palats (Wrangel Palace) in 1684, Sophia Elisabet Brenner wrote her first poem in praise of womankind.

She is the supreme image, nature’s masterpiece,

the concept of all beauty, an invaluable jewel,

prepared and composed by the gentle hand of heaven.

Hon är den Högstas Bild, Naturens Mäster-Stycke

All Deijlighets begrep, ett owärdeligt Smycke

Af Himlens milda Hand beredd och sammansatt.

With reference to the story of the Creation as told in Genesis, Mrs Brenner emphasises woman as human being. She was influenced by the French salon debate about the status of women, a discussion that reached Sweden at about this time. The Brenners’ library contained a number of erudite tracts on the subject, and Mrs Brenner’s panegyric poetry addresses the issue: she enters into discussion with those who held opposing views, gives an account of their opinions and presents counter-arguments. Is it healthy for a woman to receive an education? Would she not be corrupted, even downright depraved by study?

But were it so that woman was constructed

more weak and more unfit, as many allege,

then my argument is borne out that she should so much the more

help her reasoning, should read and study.

Men om det wore så at Qwinnan wore bygder

Mer swag och mera slem/ som mången foreger

Då styrckes mina skiäl at hon så mycket mera

Bör hielpa sitt Förnufft, bör läsa och Studera.

Men and women are certainly different, stresses Mrs Brenner. Men have far greater physical power, and it is in this that their strength lies, and the woman must be sensitive and charming. But the two sexes are of equal intelligence, and the soul is genderless, “is neither she nor he”.

The floor-length skirts in no way prevent us

from walking as easily and just as far at that

in all virtues as do our menfolk.

De sida kiortlar stå oss ingaledz i wägen

At icke wi så lät och lika långt ändå/

I alle Dygder fram som wåra Mannfolck gå.

In wedding poems, Mrs Brenner often addresses the nature of married life for the two involved parties, perhaps most often for the woman. The author gives wise counsel based on her own experience. She did not hide the fact that the role of wife was the most onerous and caused much suffering; she, who was perpetually pregnant, miscarried, gave birth and saw her children die. But the role of wife was also important. In a marriage the woman could give good advice and have an appeasing influence on her husband. Even though she believed in happy marriage, Mrs Brenner nevertheless counselled the newlyweds to be prepared for difficulties from the very outset. Concord – without a superior and a subordinate – was her ideal, and she knew that it was possible. She also endorsed the emergent view that questioned the existing law requiring the legal guardian’s endorsement of a marriage: a young woman should be allowed to reject marriage if she was presented with a prospective alliance that seemed ill-fated. “Youth should love youth!”

Sophia Elisabet Brenner was not radical in all respects. When discussing appropriate pursuits for women, she has her doubts as to astronomy and natural science:

Women who observe the moon, and among her household utensilsmoves around telescope, globe and measure, are not tolerated.

Man tål ej qwinfolck stort, som efter månen skytta,

Och bland sit husgeråd tub, glob och måttstav’ flytta.

Nor did she side with women in all matters. Of course, she thought, there are female weaknesses. A certain “softness” is indeed characteristic of many women. They are quick to tears and frequently give up when the going gets tough. Moreover, Mrs Brenner complains about women’s envy, although she also finds this in her male fellow-poets. The consequence is probably, nevertheless, that “most disgraceful sins” and “noblest of virtues” are found in both sexes.

“I respectfully petition your meeting”

In 1723 a short poem arrived at the Riksdag (Swedish Parliament), a petition in verse. Sophia Elisabet Brenner was by now over sixty years of age and had been a widow for the last six years. She had filled a central role in the literary world of the nation’s capital city, she had received honours – Sebastian Kortholt from Kiel had, for example, dedicated his De puellis poetriis (On female poets) to her – and medals had been struck with her image as eminent author. Her poems written for weddings and funerals had been extremely popular, had been respectably placed in anthologies and had not only brought her admiration, but presumably also income. By 1723, much had changed, and therefore application to the Estates of the Realm was called for:

I see however now, aristocratic sirs

And parliamentary men from our many towns,

How my condition worsens from day to gloomy day,

But since a small amount of my husband’s salary

Remains yet undisbursed, I deeply hope and pray

That you so kindly will bequeath the rest to me.

Jag ser imedlertid, Högädelborne Herrar,

Samt af de flere Ståd utwalde Herrdagsmän,

Hur’ dag från dag, ty wärr, mitt tilstand sig förwärrar;

Men som en ringa rest af lönen står igen

För min framledne Man; ty wil Jag mig förmoda,

At Ehr wälwillighet mig lembnar den til goda.

The fêted author was in financial difficulties, and she was writing to ask for the remainder of her husband’s pay. But it is not only money that is in short supply. The people who have been favourably disposed to her and supported her, financially or by distributing her poems, are either old or deceased. At this point, ten years since Poetiske Dikter was published, Mrs Brenner’s reputation as a writer is still good, but panegyric poems are no longer pouring in from near and far. She had herself often talked about ending her writing career, but at this time, in the 1720s, she is more active then ever, regaling bride and groom with printed poems or paying tribute to deceased friends and noblemen. Her petition might also show that she was in need of an income from her work. Career and promotion had naturally never been her motive for writing, but prosperous protectors and benevolent advocates of her work were at least as important to her as they were to her male colleagues. There is much to suggest that Mrs Brenner can be considered a professional author, and that she saw herself as such. Her complaints about the costs of printing, her awareness of financially viable target-groups and her combination of modesty and pride all point in that direction. “Every Swede who can read knows that I am fond of writing, / I admit that I am usually so disposed,” she wrote in the poem to the Estates.

And what happened then to Mrs Brenner? What was the response from the top of the realm? She received her husband’s outstanding pay, but that was not all: despite the nation’s overstretched economy and pressing need for a tighter budget, she was also awarded an author’s pension of 200 daler (rix-dollar) in silver coin. This is greater testimony than all else to the high regard she enjoyed in the Sweden of her day. She was not the first to be given a pension – two years earlier the Latin poet Gustaf Lithou had received one in order to enhance the glory of the nation – but she was the first woman to be afforded this honour. In the future, writers would hopefully be able to survive without having to spend most of their time as “wedding and funeral bards” or being at the mercy of benevolent supporters. And the object of this appreciation of course reacted:

I know what such grace in these hard arteries

Can accomplish. Perhaps I can once more

Lend my reputation to the good of humanity,

And express my appreciation with a worthy song

For that which has long delighted me,

And then depart from you in humble gratitude.

Ho wet hwad sådan Gunst uti de ådrar stela

För kraftig werckan har/ Kan skie Jag än en gång

Med rychtet stämmer in för menigheten hela,

Och mig erkienslig ter med någon wärdig sang,

At den man allmänt sig i långa tider fägnar,

Och tackar, se’n Jag all, Ehr än på mina wägnar.

With these concluding words to the Riksdag, in 1723, Mrs Brenner thus renders her thanks for a prospective positive response to her petition. As she fully understands that her efforts have been considered of national value, she quite logically replies with a poem which, in its choice of topic, would be a contribution to the nation’s literature: Wårs Herres och Frälsares Jesu Christi alldra heligaste Pijnos Historia (The Most Holy Passion of Our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ), with its 375 stanzas, was Mrs Brenner’s longest, and last long, poem. According to an advertisement in Stockholmske Post Tidningar (the official Swedish gazette, founded in 1645 by Queen Kristina, and the world’s oldest newspaper still being published) in 1728, the poem could be purchased from Mrs Brenner at her home on the street Hornsgatan in Stockholm.

“We should not think about Christ’s

sufferings without sorrow”

In Germany there was a centuries-old tradition for writing poems on the subject of Christ’s Passion. The story of the Passion was generally told in accordance with the biblical text. Elements of meditation and reflection were mixed with a committed narrator’s attempt to aid the reader in visualising the sequence of events. German Passion poetry was composed in keeping with Baroque stylistic ideals and the rules of rhetoric, and this was also the case with the poem Mrs Brenner wrote in thanks to the Estates. Mrs Brenner had of course read a good many poems written in her second native language, but in terms of choice of subject and approach to the Passion she had undoubtedly also been inspired by Haquin Spegel’s sermons on the Passion, which were published at around the same time as her petition to the Estates. It can be hard to spot the individual writer’s thoughts behind a poem that was written at a time when talent for imitation was the yardstick of a writer’s artistic abilities. But perhaps Mrs Brenner’s experiences as a female author nonetheless underpin her identification with the envy and jealousy that are said to be the reason for the religious powers-that-be wanting to get rid of Jesus:

He may be wise and gentle, so devout and holy,

If he is unknown to others, it makes no difference,

But if he gains renown and is mentioned everywhere,

How quickly does the praise destroy his former merits;

No, virtue is not that which inflames a man of envy,

But reputation, commendation and praise that follows virtue,

Unfortunately, it is mostly like noise in the country,

Hopefully one quality will be replaced by another.

En må så wijs, så mild, så from ell helig wara,

Blir han man obekänd så har thet ingen fara,

…

Men winner han beröm och börjar allmänt nämnas,

Få si, hwad witsord tå åt all hans förmon lämnas;

Nei dygden är thet ei, som retar afwunds man;

Men rychte, ros och prijs, som plägar föllja dygden,

Thet är’et, som ty wärr, mäst buller giör i bygden,

Hälst, någon del therwid tycks afgå for en ann.

As tastes changed in the course of the 1700s, reference to Sophia Elisabet Brenner took on a less positive tone. “The finest features of her collected writings are the plates,” according to an early history of literature.

Carl Julius Lenström: Svenska poesiens historia (The History of Swedish Poetry) was published in two parts, 1839-1840.

Ewert Wrangel notes this change of taste in his Frihetstidens odlingshistoria (1895; The Cultural History of the Age of Liberty): “Mrs Brenner, whose poetry the Gustavians laughed at for being too stiff and drily earnest, the Romantics for being too matter-of-factly moralising, and both as extremely banal and tedious, was greatly appreciated in her day, not merely as a learned woman, a new Maria Schurman, but also as an excellent practitioner of the art of poetry.”

There were not many in the early eighteenth century, says Wrangel, who treated the Swedish language so correctly and so purely. Posterity has also spoken harshly of Mrs Brenner’s Passion poem – if it gets a mention at all. It has been judged dry and boring, “a strain on the patience” says Wrangel. But there is an intensity that appeared in flashes, a gleam of emotion and trust in God, and Mrs Brenner’s contemporaries were happy to read it. When Wårs Herres och Frälsares Jesu Christi alldra heligaste Pijnos Historia was published, Jacob Frese paid tribute to her in a poem; and Mrs Brenner’s poem inspired him to write his Passions–Tankar (Reflections on the Passion). Her book was republished in 1752 – another sign of its popularity. In January 1758, Carl Christoffer Gjörwell, publisher of Den Swänska Mercurius (The Swedish Mercury), brought up the subject of Mrs Brenner in a letter to a friend. He was actually discussing Mrs Nordenflycht: “She cannot be compared, however, with Mrs Brenner, who was scholarly and at the same time a poet. I do not know if any of Mrs N.’s poetic works in the power of thought and in a number of tableaux can be compared with Mrs Brenner’s Passion poems, even though the latter had a touch of the modern French literature and taste but had not diluted her genius with it as had Mrs N.”

The depiction of Christ’s suffering gave the author of Wårs Herres och Frälsares Jesu Christi alldra heligaste Pijnos Historia cause to reflect on her own death and eternal life:

You faithful man of trust, my comfort in despair.

Who for my sake the pain of death did choose to bear,

When my poor soul once more shall cloak itself in skin,

Let then your fate requite me with bleesednessness and peace,

To gaze upon your face, the ultimate release,

Absolved at least through you from judgement and from sin.

Then I will sing your praise with greater ecstasy

And give you all I have, though neither tone nor key

Are half as eloquent as spirit would demand,

But teach me then the lesson through your most holy spirit,

Lend me your help and kind support that I might somehow hear it,

And I will find a way to please, your servant close at hand.

Min trogne Löfftes-Man, min tilförsicht i nöden!

Tu, som for min skull här äst worden dömt til döden;

När som min Siäl på nytt med kiöt skal klädas om

Lätt tå tin dödsdom mig til salig fördehl lända,

At iag tit ansichte må skåda utan ända,

Frikallat genom tig, för rättegång och dom.

Tå skal iag tig til pris, en bättre lofsång siunga;

Här biuder iag wäl til, fast hwarken tohn ell’ tunga

Så redebogen fins, som andan willig är;

Men underwijs tu then igenom tinom anda,

Lätt then, med råd och hielp, mig framgent gå tilhanda,

Så hittar iag wäl på hwad tig behaga lär.

Sophia Elisabet Brenner had but a few years of her life left. The seventy-year-old author – “wår swenska Minerva” (our Swedish Minerva), as the later professor of poetry in Åbo, Torsten Rudeen, referred to her in a poem written in her honour – came to the end of her active life in 1730, celebrated and respected as a scholar and as a woman of advanced years. “For women the case is usually that/ Immortal name is seldom theirs;/ They cannot endure the smell of gunpowder,” wrote Petrus Hesselius, the author of a versified description of biblical women, written when he and Mrs Brenner used to exchange courtesies and ideas on the ethical upbringing of women. Mrs Brenner succeeded in breaking through the wall of silence and lack of interest that generally surrounded women writers in her day.

Sophia Elisabet Brenner was not, of course, the first woman in Sweden to produce literature; and numerous other women were putting pen to paper during her lifetime. Aurora Königsmarck and Ebba Maria de la Gardie were two such, but they only wrote for their friends and “did not seek acclaim as an author”. Their writings were not published, and therefore only came to the notice of a wider readership at a much later date. Sophia Elisabet Brenner was the first woman in Sweden whose poetry was of such a standard that it was published immediately and made her well-known. Moreover, for reasons of linguistic patriotism, she consciously elected to write in Swedish, alongside the major international languages of the day.

Bernt Olssons as yet unpublished study of word frequency in the Swedish literature of the seventeenth and eighteenth century reveals a highly varied language use with many unique words in Mrs. Brenner’s poetry. This could be due to language patriotism.

She was aware of her worth as a woman in relation to men, and she was aware of the problems she and her Swedish sisters faced. And she helped to introduce the international discussion on women and education into Sweden. She motivated her future son-in-law Petrus Hedengrahn to write a dissertation on learned women, and she played an active part in the making of this Mulieres philosophantes (1699; Women Philosophers). She certainly shared the views of women’s intellectual properties and potential for study as he presented them; views which were typical of the seventeenth-century European debate. When all is said and done, her most original contribution was probably that she reassigned the humanist belief in ‘mankind’ so that it applied to womankind as well.

Karin Westman Berg og Valborg Lindgärde

You, Most Distinguished Issue of the Muses

– On Brenner’s Correspondence Written in Latin

Sophia Elisabet Brenner is deservedly best known for her poems written in Swedish. Like the other Nordic countries at the time, Sweden was not overrun with good poetry written in the national language. Besides her poetry, however, there is a smaller work from her hand that, although it was written without any actual artistic ambition, gives an insight into her environment, her knowledge and skills, working conditions, self-image and so on – all of which is part of the literary setting for her writing. The work in question is a by and large unedited collection of just over thirty letters and brief notes written in Latin to and from Sophia Elisabet Brenner. The letters were written in the course of a dozen or so years and are kept (with one exception) unpublished at the Royal Library in Copenhagen. The collection is in itself a unique account not just of her as an individual, but of one of the Nordic region’s learned women in general. One drawing of a flower comes from her hand, as do nine of the letters either in the original or in the addressee’s transcription in his notebook. The addressee was the Dane Otto Sperling Jr.; he sent her letters and also a poem in Latin.

The correspondence spans more than ten years, from 1696 until 1708. There are three clear themes: learned women, the letter-writers themselves and numismatics (i.e. the study of coins). Sophia Elisabet Brenner’s husband, Elias Brenner, was a well-known numismatist and he was in contact with Otto Sperling, who had a large coin collection and was renowned abroad for his knowledge on the subject. Otto Sperling’s correspondence with Sophia Elisabet Brenner reveals that she herself was not uninformed when it came to numismatic matters. In his later biography of her in De foeminis doctis (On the learned women), Sperling even writes that “she helped her husband to write his treatises”.

Sperling was particularly interested in who Sophia Elisabet Brenner was as a person, and it is that aspect of the letters which will be considered herein. He had been aware of her for a while, but had not attempted to make contact with her, when, at some point around 1696, he was presented with poems written by her in Latin, Swedish, German, French and Italian; he was so excited and impressed by her work that he wrote to her. Publication of her Poetiske Dikter (Poetic Writings) in book form was still a thing of the future, and it is not improbable that Sperling helped to bring about the first edition, published in 1713 – in which, what is more, this letter was printed, the only one from the collection to be reproduced.

In his letter he tells her that he is writing “a small work on the subject of learned women” (opusculum de eruditis foeminis). The work treats of women “who in their writings have recorded knowledge for the benefit of the world of scholarship”. He has already included two Swedes, Katarina Baath and Catarina Gyllengrip. Sure enough, they are in the manuscript as numbers 550 and 551. The letter makes no mention of Queen Christina, possibly because he does not think of her as Swedish. She is no. 161 in his catalogue. Brenner herself is no. 728. Sperling asks for information about any other Swedish learned women: she must surely know of them, if they exist.

Having thus softened her up and prevented her from excusing herself from answering for reasons of modesty – as would have been expected of a lady – he moves on to the key purpose of the letter: to ask for her curriculum vitae. Otto Sperling here addresses her appropriately as “Doctissima Foeminarum” (you most learned of women):

“Yet may I be permitted to request this one thing of you – you most learned of women – that you will not shrink from writing down your biography for me.”

“Oh, you, most distinguished issue of the Muses” (Nobilissima Musarum proles) – is how Otto Sperling referred to Sophia Elisabet Brenner, using one of the high-flown terms of homage applied to learned women.

Sperling informs her that he has already received life stories from other learned and renowned women: Anne Margrethe Qvitzow in Denmark, for example, whose four-page curriculum-letter written in Latin is preserved in her own handwriting, and from the Italian scholar Helena Corner, to whom he refers by two of her Latinised names, Piscopia Cornara. Helena Corner’s letter, which was presumably also written in Latin, has not survived, but a long article about her in Sperling’s De foeminis doctis shows that he gathered material on her with great interest.

A brief and not very informative note on Sophia Elisabet Brenner, written in Swedish (kept in the third-person singular, not in the first person), has survived. It is inserted into Sperling’s treatise on the learned women. She might well have written it herself. The writer remarks, for example, that due to modesty (modestia) he/she will add no further details besides the few listed on this half page. Who but herself would have had scruples about mentioning her in flattering terms? The Latin correspondence does not contain an actual curriculum vitae, but does provide sufficient answers to concrete questions of a biographical nature: as regards her origins, for example. On the other hand, the second edition of her Poetiske Dikter, 1732, includes a four-page autobiography in German.

The passages touching on their relationship are evocative; a dialogue in letters between two evenly-matched middle-aged – and gradually ageing – people. Never having met, they work through the one finely-turned civility after the other, until at length they feel a degree of closeness. Sophia Elisabet Brenner has difficulty in finding time to write. Work in the house and the children weigh heavily on her time: fifteen infants born alive, states the brief autobiography written in German. Otto Sperling understands her predicament, but encourages her not to give up. Do not lose confidence in the strength of your shoulders, he writes in 1699. They can bear more. If you want to do something, then you can. I have no doubt about that. “Domestic work must, of course, be done, but you must not neglect studies and writing – you, most distinguished issue of the Muses.”

The need to become properly acquainted with one another grows gradually as the correspondence proceeds. In a meandering run-on sentence written in 1705, which like much Neo-Latin epistolarly literature is understandable but absolutely not of a classical-orthodox structure, Sophia Elisabet warmly declares her hope of seeing him in person: “What pleasure, what advantage would I not gain, if I could speak face to face with you, be there where you were, and open my heart; that it is scarcely to be hoped for, is a circumstance I would request you not to allow to diminish your favourable feelings; perhaps it is the will of the gods that our relationship shall be the stronger and closer given that, by their decree, we live far from one another.”

Otto Sperling also considered the possibility of meeting. At one point he laments that he is now looking old. At another point he has contemplated himself rather near to her. Folded inside a letter from her to him, there is a rough draft of a poem from him to her. We do not know if it was ever sent. Nor can we know if she was simply being a Muse and inspiration for his own attempt at writing verse in Latin, or if he divulged his feelings in the poem and wrote what he would liked to have dared say. The poem is written in elegiac metre, the classical metre for love poetry, comprising alternating lines of dactylic hexameter and pentameter. The exact meaning is enigmatic and problematic in terms of language – for example, the use of words such as vetera (old) and demere (remove) – but the poem invites the attempt (even though it will be erroneous in some places) of making a versified version, which could look something like this:

Oscula cum mittam, Tibi non nisi mitto pudica,

Sique minus placeant coetera, sunt vetera.

Et si, quod nolim, si offendunt ista pudorem,

Tuque pudorque Tuus tollat et ejiciat.

Sic volo; vel quidquam si demere forte timebis,

Nomine iam fient cuncta pudica Tuo

Kisses, which I send to you, are only sent if the kiss is chaste.

Others, if you would rather be without, we will just call ‘old’.

Should those first – I hope not – offend your bashfulness, throw the kisses away.

You and your chasteness may rebuff them.

That is my wish. But should you fear to remove something

– all is chaste again, purified by your name.

Correspondence such as that between Sophia Elisabet Brenner and Otto Sperling renders it impossible to decipher messages relating to their innermost hopes, pleasures and disappointments. However, it is possible, and with greater certainty, to assess the cultural environment in which the letters place their writers. Writing fluently in Latin was, of course, the prerogative of the few, particularly where women were concerned. Brenner’s style is unforced, as is Sperling’s. They use a utilitarian Latin based on the language of classical antiquity. A language which, even though it is literary and takes its models from written rather than spoken sources, primarily Golden Age Latin, nonetheless permits self-invented words, ‘improper’ sentence and clause structure, and run-on sentences ending in the ‘wrong’ tense or mode – now and then even syntactically ‘wrong’ – by means of which the language comes alive. Someone speaking or writing such a language has natural rights which others do not have.

Letters like those between Brenner and Sperling might well be virtuous, but the purity has undertones only permissible if elegantly employed – as they are here. Their correspondence reveals an aspect of the learned women’s licence. When writing in Latin, women might freely record affectionate, warm feelings without being accused of impropriety. And they could receive similar letters from men who were in effect strangers to them. Married women could even show these letters to their husbands. Sophia Elisabet would no doubt often have received her letters from Sperling as enclosures in letters sent to her husband. Latin seems cold and stiff to someone who is not on top of it. But once inside the Neo-Latin cultural circle there was, not least for a woman, a language in which to say what you liked, and which others would envy if they could but understand what was going on. Women’s scholarship was not exclusively a cause of male anxiety; many men found it entertaining, stimulating and challenging. The learned women compelled respect and humour from the men, and both parties thereby achieved an intellectual community that cut across the sexes – and was by no means as sexless as it might seem when viewed from the outside.

Marianne Alenius

Translated by Gaye Kynoch