On 15 November 1764, Lärda Tidningar printed the following: “Good Lord! How often do we not hear complaints about the absence of inspiration, zeal and love for science, art and useful establishments; but nobody speaks of the real reasons: nobody notices the dearth of encouragement that can be found among our ranks, how rarely a person is rewarded for the good he has accomplished: yes, how frequently such achievements are not even mentioned but simply consigned to eternal obscurity.”

Lars Salvius (1706-1773) was printer, publisher and bookseller, public commentator on issues of economy and language, and member of Kungliga Vetenskapsakademien (the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences). From 1745 until his death, he published Lärda Tidningar, a learned journal presenting scholarly literature, lectures held at Vetenskapsakademien and articles for the general public.

The passage refers to the literary activities of Maria Gustava Gyllenstierna (1672-1737). She is characterised as “a woman of great talent and noble heritage, who has honoured her Country and her Sex in these our times.”

So who was this Countess Gyllenstierna? She is considered to be one of the skilled literary women of the time; she is listed in contemporary catalogues of Lärda Swenska Fruentimmer (Learned Swedish Women) and she is described as such in the directory of Swedish nobility. She was the second wife of Privy Councillor Carl Bonde and bore him five children, all the while accompanying him on trips to, among other places, Finland and England. He died in 1699. Maria Gustava Gyllenstierna was a widow for nearly forty years, during which time she devoted herself to her writing at Tyresö Castle just outside Stockholm.

Stockholms Magazin, April 1780, printed information on twenty-three learned women taken from von Stiernman’s unpublished work Gynæceum Sveciæ Litteratum eller Afhandling om Lärda Swenska Fruentimmer (Treatise on Learned Swedish Women).

Translation

Translations from German and French made up a large part of her literary output. Flavius Josephus, a Jewish historian who lived in the first century AD, wrote an extensive history of the Jewish people (Antiquities of the Jews), which Maria Gustava Gyllenstierna translated from a seventeenth-century French edition. Sophia Elisabet Brenner paid tribute to this work in a poem, 1713:

It lends our entire sex, Most Gracious Countess,

Exceeding grace and honour, and you as well,

That Josephus has been attired in Swedish garb

By such a splendid and virtuous woman.

Det länder alt wårt kiön, Min Nådigste Grefwinna

Til mercklig prydnad och til heder, jemte Ehr,

At man Josephum klädd i Swenska kläder seer

Af en så Högförnäm och Dygdfullkommen Qwinna.

It might seem strange that this particular work appealed to the translator in Countess Gyllenstierna. One explanation could be that scholarly circles in seventeenth-century Uppsala were interested in the study of Hebrew and Oriental languages, in the Jewish faith and rabbinic teachings. The peak period for these studies occurred in the decades around the year 1700, and they were often nourished by study trips abroad and contact with rabbinic scholars and with Jewish piety. This new world was brought to the Swedish Lutherans via travel diaries, and when the travelling academics returned home they passed on what they had learned. Perhaps this was how Maria Gustava Gyllenstierna’s interest in Jewish history was aroused, and she must also have had an ambition to translate a well-known work into Swedish. In her tribute poem, Sophia Elisabet Brenner is particularly impressed with this translation as an achievement of national importance:

Josephus’ learned writings are read in many a tongue,

But he who only Swedish and no other language knows

Has found himself at bay and lost beyond a clue

To learn the story of the Jews and of their exploits.

Man läs i många språk Josephi lärda Skriffter,

Men den, som intet språk, än blott sin Swenska kan,

Har härtils stått sig slätt, och warit brydd, om han

Haft lust at weta grund, om Juda Folcks bedriffter.

In the opinion of Lärda Tidningar, “it is easy to imagine that this extensive work has not been the least part of the distinguished author’s productivity”. Maria Gustava Gyllenstierna was an industrious translator. She translated Dorothe Engelbretsdatter’s Taare–Offer into Swedish, and also Gottlieb Creutzberg’s eighty devotions on the Passion, Wahre Seelen–Ruche in den Wunden Jesu, oder achtzig Passions–Andachten (True Repose of the Soul in Jesu’s Wounds, or Eighty Devotions on the Passion), both in 1727, although the latter was never printed. Her translation work placed Maria Gustava Gyllenstierna within a Swedish literary tradition: it was quite common in the seventeenth century for women of the aristocracy to translate, compile or write devotional books. Much devotional literature was translated during the course of the century, mainly from German or via German, for a target readership often made up of noblewomen whose proficiency in foreign languages was not such that they could read these works in the original language. In many instances, however, noblewomen with a greater proficiency in foreign languages translated devotional works for “those who know no language other than their Swedish”, as Sophia Elisabet Brenner put it. Catharina Gyllengrip’s 1670 translation from German of Martin Hyller’s Güldenes Schatzkästlein (Swedish title: Gyllene Skatkista; Golden Treasury), the most distinguished work of Passion piety to be found in Swedish, is one example of this devotional literature brought in from abroad. Other devotional books were compiled as collections or were copies, meaning that an individual text might feature in various devotional books. At a time in which her family was hard hit by the Swedish crown’s confiscation of noble property, Maria Euphrosyne de la Gardie, married to an uncle of Aurora Königsmarck’s cousins, compiled an extensive devotional book covering works by the influential writers on piety. Many handwritten devotional books have of course disappeared over the years, even though a number have been preserved as family treasures. At the end of the nineteenth century the descendants of Märta Berendes still had the book she had filled, in the second half of the seventeenth century, with thoughts, prayers and the story of her life. Any prayers not written by Märta Berendes herself had been copied into the book. Below one of the prayers we read that she has copied it from her mother-in-law Ebba Oxenstierna’s book.

Another prayer is signed AMP, interpreted as meaning Anna Maria Posse, Märta Berendes’ sister-in-law. Countess Gyllenstierna’s translations of edifying devotional literature were thus prepared for publication within this tradition of the pious aristocratic female pen.

A lengthy search for Märta Berendes’ prayer book ended with success in the autumn of 1990. Using the directory of the nobility, and telephone books, it was possible to trace the family member who was known to have been in possession of the old handwritten book a century earlier.

Sonnets on Jesus’ Life, Suffering and Death

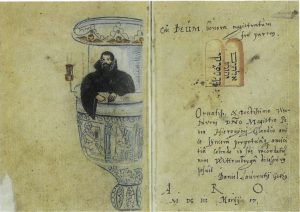

The mention in Lärda Tidningar of Maria Gustava Gyllenstierna’s literary output probably also referred to works only found in manuscript form. These manuscripts are also of interest because they testify to her literary ambitions and, moreover, to her manifest efforts to join the ranks of learned women. Om Menniskornas fahl och uprättelse, Betrachtade Widh Wårs Herres och frälsares, Jesu Christij, Heliga Mandoms anammelse, födelse, hel: lefwerne, pino, och död, samt upståndelse och Himblafärdh

“On the fall and rehabilitation of humankind, exemplified in our Lord and Saviour’s, Jesu Christi, holy incarnation in human form, birth, holy life, suffering and death, and also resurrection and ascension.”

is the long title of an extensive work in four parts, of which the first three are preserved in three notebooks written in Maria Gustava Gyllenstierna’s own elegant handwriting. The fourth part has presumably been lost, or perhaps it was never completed. On the flyleaf of the first part we see the date 1730, and in the third part Queen Ulrika Eleonora’s handwriting tells us that the book had been brought from Tyresö in 1734, some years before its author died. The approximately 500 sonnets place the writer in a European literary tradition. An ingredient of the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century renaissance in Passion piety, both Catholic and Protestant piety, was to depict the life of Jesus and, above all, his suffering and death, in regular stanzaic form. The Bible epic was considered to be the Christian world’s answer to the ancient classical and pagan epic works, and it is thus an elevated and venerable genre. When Countess Gyllenstierna writes a eulogy to Johan Paulinus-Lillienstedt, in which she praises him for the “apposite” poems he had written thirty years previously, she is paying homage to a predecessor in this very same genre.

An earlier and a late example of German writings on the Passion: Die Histori des Leidens vnd Sterbens/ vnsers einigen Erlösers by M. Schneider was published in 1629; Der leidende Jesus, oder die Geschichte des Leidens und Sterbens unsers Herrn Jesu Christi by Phil. Ernst Kern was published in 1760. In Denmark, Elias Naur’s long and scholarly Passion verse epic Golgotha paa Parnasso (Golgotha on Parnassus) was published in 1689.

While Maria Gustava Gyllenstierna was working on her sonnets about the life and death of Jesus, two long Passion poems were published in Sweden: one by Sophia Elisabet Brenner and one by Jacob Frese. Apart from their choice of subject, the three writers would seem to share their source of inspiration: Haquin Spegel’s collection of sermons on Christ’s suffering and death.

Haquin Spegel (1645-1714), who at his death was Archbishop of Uppsala, was one of Sweden’s foremost hymn writers. In 1671 he had been appointed chaplain to Queen Hedvig Eleonora, and it was as such that he held his sermons on the Passion subsequently published in 1723 and in 1727.

They have other similarities, by reason of the genre, which are also found in later representatives of Passion writing in the Swedish literary tradition. The poems mix meditation with exegeses, interpretations and explanations in the sermon tradition, and with retellings of the episodes of the Passion. A description of events at Golgotha, as witnessed by one of those present, is also an ingredient of the genre. Like other writers in this genre, Maria Gustava Gyllenstierna is at home in the biblical language and exegeses, but unlike, for example, Sophia Elisabet Brenner and Jacob Frese, she is not primarily interested in the devotional and didactic aspects of the subject, but more in providing a commentary to the Bible stories. She thus uses footnotes to cite her reading of contemporaneous literature – thereby demonstrating the level of academic education obtainable for a pious woman from the upper social strata. With reference to Talander’s travel book Curieuse und Historische Reisen durch Europa, 1698, she writes that the widow’s son at Nain was called “Matteus”, and that he later became bishop in Trier. Erland Dryselius’ Kyrkohistoria över Nya Testamentet (1708; Ecclesiastical History of the New Testament) contributes with the information that Lazarus preached God’s word in Marseille, where he suffered martyrdom. The popular English preacher and devotional writer Jeremy Taylor is also quoted on a number of occasions, but even here it is still primarily the stuff of tradition that is passed on. The informative Countess also noted that the Eucharist was instituted on the 2nd of April, and Good Friday that year fell on the 3rd of April. It is obvious that Countess Gyllenstierna was deeply committed to the subject matter of the sonnet collection; this commitment was again evident in 1722 when she donated eight paintings with motifs from the life of Christ to Tyresö church – and she, in addition, may have presented the painting Smärtomannen (Man of Sorrows) to the church.

Her willingness, like that of her sister-writer Sophia Elisabet Brenner, to tackle a genre with such exacting requirements in the literary tradition, is evidence of her self-image as writer. Maria Gustava Gyllenstierna gives another indication of this self-image in 1730 when paying tribute to the recently deceased Sophia Elisabet Brenner, “Our Dear Lady Poet”, as the sonnet says. Normally the Countess had no need to pay tribute in a poem to anyone other than those above her on the social ladder. Mrs Brenner’s poem on Christ’s suffering and death receives particular attention in the funeral poem:

She reaps her just rewards for what she earned on Earth,

Immortal honour’s name, for virtuous conduct praised,

Esteemed with passion here as a God-fearing woman,

May you, SOPHIA BRENNER, enjoy heavenly bliss.

Ty billigt Henne ges, hwad högt Hon want på Jorden,

Odödligt Heders Nambn, för dygd-förd wandel skär,

För sann Gudsfruchtan med Passion betrachtad här,

SOPHIA BRENNER ty, och säll i Himblen worden.

Maria Gustava Gyllenstierna’s “Spiritual and Temporal Poetry”

Other manuscript material has also survived, most of it written between 1710 and 1720. It contains “spiritual and temporal poetry” and is “written in my own hand”. On the flyleaf, a different hand tells us that this “is the same Countess who translated Josephus’ Jewish History into Swedish”. Maria Gustava Gyllenstierna conceals her initials in expressions such as “Mein Gott Ge Singt” ([I have] sung to God) and “I kärlek, tro och hopp Iagh Min Gudz Godhet Spör” (In love, faith and hope I feel the goodness of God), which would suggest that she felt spiritual writing was her true home.

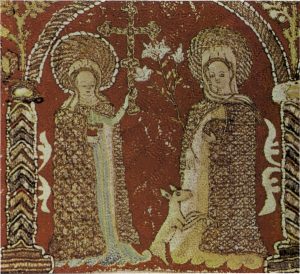

The poems referring to Passion piety are of particular importance; “Om Christij pina och siu ord” (Of Christ’s Suffering and Seven Words) fills sixteen closely-written pages, and there are short verses based on Creutzberg’s Passion devotions. Among other spiritual texts – on the world and its vanity, and on the longing for the heavenly home – we notice the translation of a poem alongside which “på tyska aff M: årå K mark” (in German by M: årå K mark) is written in the margin. The poem, with the title “Jerusalem O du helga Gudz Stadh” (Jerusalem, O Holy City of God), is found in its original German in Aurora Königsmarck’s collection of poems, her own as well as her sister’s and the de la Gardie sisters, Der Nordische Weihrauch, oder zusammengesuchte Andachten von schwedischen Frauenzimmern. The Jerusalem-poem would suggest that Countess Gyllenstierna had access to this handwritten poetry book, which had been put together some years earlier in the pious court circle around Ulrika Eleonora the Elder. The information might also suggest the Countess’s spiritual kinship with the element of more fervent piety at court, which presumably lived on after the period in which the Königsmarck and de la Gardie sisters, together with Märta Berendes, formed a pious and spiritual circle of friends around the queen. This also applies to her daughter Ulrika Eleonora the Younger, the queen whose most cherished reading is said to have been the Passion devotions of Danish theologian Johan Lassenius, to whom Maria Gustava Gyllenstierna dedicated her sonnets on the life, suffering and death of Christ.

His other word most comforting is

Who our suffering willingly bears

In this poor world’s misery.

And we who have his mother seen

Know he has not forsaken her

Nor let her stand defencelessly.

Therefore this hope we also cherish

That in our wanderings far and near

He never will abandon us

In our adversity and want

For he upon his manhood took

Our loving brother ever to be.

From Maria Gustava Gyllenstierna’s poem on Christ’s words from the Cross.

Between the poems in this wide-ranging handwritten book there are also some song-like texts in which we find, here and there, a use of the language preferred by Pietist song. “Drag skönsta Jesu migh till tigh” (Draw me, sweet Jesus, close to you) as we read in one of her hymns, which employs a favourite verb of the Pietists. Here we also find the natural trust in God that came from reading the devotional meditations. Maria Gustava Gyllenstierna has, with the information that it “går som, rätt hiärtlig iag längtar” (that is, that the hymn is sung to the same tune as “Ret hjertelig jeg længes”), translated a hymn from German, the first stanza of which reads:

I will not forsake you if you comfort me,

nor will I forget you, for I have chosen you

to be my dear child. I am your faithful God,

you must not be alarmed, neither for want nor hardship.

Iagh will tig eij förlåtta, om tu på tröstar mig,

eij häller tig förgätta ty uthwalt har iag tig

til barnet mitt dett Kära, iag är tin trogna Gudh

eij må tu tig förfära, för någon nödh ell’ trugh.

However, Maria Gustava Gyllenstierna’s extensive writings also cover “werldsliga Poesier” (temporal poetry). Like Sophia Elisabet Brenner, she took part in the court’s intense celebration of special days; she wrote occasional poems which, for the most part, celebrated members of the royal family on their name days, homecoming from journeys, Ulrika Eleonora on her wedding day, 25 March 1715, and so forth. Two sonnets, written on 25 and 28 February 1715, lament the years of crop failure and hardship. The hardship is seen as the punishment of a “recalcitrant child”, resulting in sorrow for those at home and imprisonment for those in distant lands. She adds a prayer asking: “that You bless the one who, like Job, You have nearly beaten.”

As often as not it was the kinswomen who embodied contemporaneous interest in writing family history and chronicling the glorious achievements of family members. Countess Gyllenstierna, for example, wrote a long poem with a family history based on her father’s “heraldic device and shield, which are mounted in Tyresö church”, and she versified her thoughts as she stood by the graves of her ancestors.

Perhaps this goes some way towards explaining Countess Gyllenstierna’s keen translator’s pen and her own writings. The male members of the family, her forefathers and her husband, could fight for their country on the battlefield, or contribute to the growth of Sweden’s power by holding weighty public posts. Translation and writings of a sacred nature were, of course, not a route by means of which a woman in the 1700s could qualify herself to high social office, but she could instead make her contribution to the glory of the nation by being erudite, widely read, having knowledge of foreign languages and, furthermore, by supporting the established order of power and authority in panegyric poetry.

Did Maria Gustava Gyllenstierna create an image of herself as ‘woman’ in her writings? It is an intrepid writer who tackles the Bible epic, a respected and valued genre, and it is interesting to see that two Swedish women were working on the theme. Specific rules obtain, and there are ready-made patterns to be followed, and so it is not always easy to spot the writer’s own thoughts behind the text. In Maria Gustava Gyllenstierna’s sonnets on the suffering and death of Christ, however, one section is underscored, most likely by her own pen. The passage in question deals with Pilate’s wife; the sermon tradition often singled her out as a female object of identification on account of her independent line of action and her ability to accept sound advice rather than simply, like her husband, anxiously defer to power. Maria Gustava Gyllenstierna writes:

It is of course proper for a wife gently to tell

her husband her devout thoughts when necessary,

particularly when she sees that he is embarking on an evil path;

wise women’s advice bears import, their deliberations are judicious;

the advice of a pious, vigilant wife prevents many a misfortune.

A God-fearing man acquires just such a wife;

from zealous love of God she provides her husband with the best counsel;

blessed is the man whom God allots such a wife.

Wähl anstår thet Ehn fru, att Hoon Sachtmodigt säger;

Sin mann när thet behöfs, Gudfruchtig tankar sin,

Hälst tå på Ehn ond’ wägh, Hoon seer, han träder ihn,

Wijss’ Qwinnors rådh har wicht, förnufftigt the omwäger;

From, waksam Hustrus rådh, Olyckor mång’ afböijer.

Ehn mann som fruchtar Gudh, slik’ dygdig qwinna får,

Hon af Gudälskand’ nijt, sin mann thet bästa råår;

Säll är then mann, som Gudh, slik hustru from tilföijer.

Maria Gustava Gyllenstierna might not always have succeeded in making her rhyme flow and her verses supple, but she was clearly proficient in languages and she was an energetic reader; she was quite rightly accorded a place among the learned writing women of the day, and they were important for a country which claimed the status of a Great Power. “En af Sweriges Heders Fruer” (One of Sweden’s Illustrious Ladies) wrote Olof von Dalin in his funeral poem to the Countess. Perhaps she was also something more. In his sermon at her interment, the clergyman Jacob Strengbom wrote that Maria Gustava Gyllenstierna:

“Demonstrated thus by her example, that it is not only the lot of the man to be able to embellish the mind with scholarly erudition and make judicious use thereof.”

Translated by Gaye Kynoch