In the seventeenth century, lengthy study trips undertaken as part of a political or military career were a male privilege; active military service also took men on long journeys through Europe. Quite a lot of women chose to accompany their husbands on these latter expeditions, preferring to endure a nomadic life travelling in bumpy carriages between inns and army camps in the Baltic region and Germany, endangering their own and their children’s health, rather than risk losing touch with their husbands. This life on the road is described in surviving letters and travel accounts written by, for example, Anna Agriconia Åkerhielm, Agneta Horn, Sophie Brahe and many others. Leonora Christina and Queen Christina were also widely-travelled.

Young noblemen, in the main, but also the less wealthy sons of public officials and clergy, often concluded their education with the Grand Tour, a kind of finishing school travelling through Europe, with the less affluent acting as guides or tutors for the young aristocrats.

Their sisters had to keep any desire to study or longing to travel to themselves, and were obliged to concentrate on more close-at-hand practical tasks. However, thanks to these women, life at home was documented in genealogies, in autobiographies and in diaries.

Seventeenth-Century Friendship Albums

When European travel and cultural exchange took off again after the turbulence of the Reformation, friendship albums were often taken along in the luggage of the travelling students, noblemen and public officials. Friends and acquaintances or famous scholars and teachers would sign their names, often supplementing their autograph with a maxim, a piece of advice or some other wise saying. The Bible and the writers of antiquity were popular sources. Those of an artistic or poetic disposition would happily append a drawing or a poem, the latter quoted or of their own making. Some albums would include paper cut-outs or drawn silhouettes of friends whom the owner of the book wanted to keep in mind.

“Spes mea Christus” (Christ is my hope), “All mein Hofnung in Gott” (All my hope in God) can be read in Daniel Hermann’s (1543-1601) friendship album from 1579. The book also contains quotations in Latin and Greek from Horace, Cicero, Pliny, Ovid, Cato, Bernhardus, Isocrates, Sophocles, Plato and Menander.

The university town of Wittenberg is usually identified as the spot where the student population developed the practice of writing in each other’s friendship books. This custom then spread through Protestant Germany and the Nordic region. By means of these books or albums, which are often small in size, we follow the traveller’s journey between various universities and visits to famous teachers. The route might go via Wittenberg, Leipzig, Jena and Leiden to Paris and home again. Sometimes these foreign travels would last a year, sometimes ten or fifteen years.

The friendship books also, of course, functioned as a kind of travel diary and memoir that could be shown around once the traveller had returned home. The friendship books might also have had their uses by way of introduction at the new seat of learning: look at this, I know these distinguished people, I have listened to the words of this teacher, I come from a reputable family, and I too am ambitious. Teachers at the universities might also have seen some benefit in the albums; it was a way in which their names could be circulated among colleagues working elsewhere in Europe.

Martin Nordeman’s (1636-1684) album contains many maxims written by his tutors and friends in Uppsala before he left to travel abroad in 1663: “Nemo scit, quantum nesciat” (No one knows how much he does not know).

“Peregrinatio vita est mortalium” (Life is a pilgrimage for the mortal). “Vita sine Litteris est vivi hominis sepultura” (A life without books is a living tomb for man). “Suffïcit mihi gratia Dei” (The grace of God is enough for me).

Our archives contain surviving sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Swedish, Norwegian, and Danish friendship albums. The genre had its initial boom in the first half of the seventeenth century, after which interest waned and then grew again in the eighteenth century.

One of the extant friendship books from the first blossoming was compiled by a woman, Kristina Posse (1630-1668). She was the daughter of Chancellor Axel Oxenstierna’s sister, and her friendship book followed the preferred blueprint of opening with a royal autograph: Queen Christina wrote her name on the first page in 1648, after which Count Palatine Karl Gustaf added his signature.

We then read many names from the court milieu to which Kristina Posse’s relatives and friends belonged. Maria Euphrosyne signed in 1648, as did Beata de la Gardie and Beata Leijonhufvud, and in 1651 Agneta Horn, a relative of the same age as Kristina, added her name to the friendship book.

It is as a source of information about acquaintances and friends, the circles in which the owner of the book at any given dated entry moved, that the friendship albums are of greatest interest. The poetry quotations and the maxims also reflect the cultural history and ideals of the times.

Around the year 1700, one of Sweden’s learned women, Mrs Brenner, was considered the foremost author in the Nordic countries. Travellers and young scholars visited her home, and she and her husband wrote inscriptions in the friendship books. One such caller was twenty-two-year-old Erik Benzelius the Younger, who visited the Brenners in the spring of 1697 at the outset of his lengthy European travels.

Family Books

“Few Scanian women have a more deserved reputation than Sophie Brahe, Tycho’s sister. She stands for something new in the Nordic woman’s history,” wrote the historian Lauritz Weibull more than a century ago. “She is the first and one of the most reliable representatives in the Nordic countries of the Renaissance ideal of womanhood, governed by a fervent devotion to science and art […].”

Sophie Brahe (1556-1643) came from a family that had already shown interest in its own history. Her father’s paternal aunt, Elsebe Brahe, wrote a family book in 1553; her own paternal aunt, Magdalena Brahe, was the genealogical oracle of her day in Scania; some of her brother’s sons wrote family history books, and, finally, her paternal grandmother had a family book compiled. The same interest was also manifest in Sophie Brahe’s maternal – Bille – family.

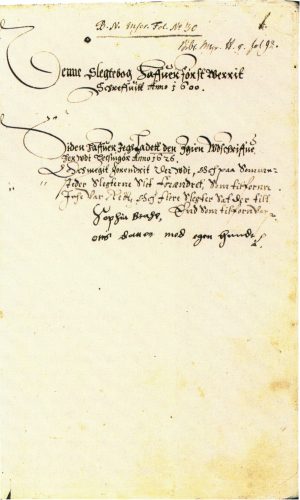

She has left us with her own family history book, a folio of more than 900 pages. It has been described as the highlight among a number of similar works compiled in Denmark at a time when the nation included the now Swedish provinces of Scania, Halland and Blekinge. The original manuscript is now kept in the Lund University Library; the first page tells us that it was written in Elsinore in 1626, but Sophie actually continued adding to the work right up until her death.

Sophie Brahe had finished work on her first family book in 1600, but she had not been satisfied with it. Once widowed and settled in Elsinore, Denmark, after many years living abroad, she resumed her genealogical studies and made a new version of the book.

We can follow the preliminary work for the family book in a collection of her copy books, in which her secretary’s notes often have riders added in Sophie’s own handwriting. The copy books contain genealogies of Scanian branches of the family, letters concerning the ancestry, and in three of them there are letters dated from the 1630s and 1640s with family lists and individual historical information – all of which demonstrates her lifelong interest in genealogy and the great efforts she made to obtain facts from various sources.

Sophie Brahe’s family history book follows the same pattern as other works in the genre from that period. Her own family, and its various branches, is the main topic; family traditions had been carefully passed on from parents to children and therefore her information about, above all, the Bille and Brahe families is exceptionally accurate. Many other well-known families who married into the lineage are also recorded: Krabbe, Lindenou, Sparre, Thott, Ulfeldt and Urne, for example.

The copy books also document Sophie Brahe’s correspondence with other women interested in genealogy, such as Sophie Below (1590-1650) and Beate Huitfeld; these letters included many personal stories, which form the background for the brief biographical notes in the family book. The correspondents exchanged information and help with finding sources. In 1634 Sophie Below began work on her own family history book, which would be continued after her death by her daughters Anne and Birgitte Thott. The latter had a fair copy of the book made in 1659, and she supplied it with a preface from her own pen.

“Sister of my heart,” writes Beate Huitfeld in a letter to Sophie Brahe:

“Are you aware that you and I have a great-grandfather in common? Were not Mrs Lisbet, Mr Klaus Bille’s mother, and my mother’s father two siblings and twins at that, born at once, the one an hour older than the other? See in you family book if you have not 4 great-grandfathers and 4 great-grandmothers in the male line.”

The detailed letters show how discussion was based on a lively interest in individual biography and family history and how the correspondents helped one another with source references, the historical accuracy of which was not, however, always easy to assess. Sophie Brahe also used the copy books to make written accounts of information she had received verbally; in so doing, she provided samples of her stylistic and dramatic skills, which might read as follows: In the 1400s, widow Else Krogenosz was engaged in a legal dispute with one Otte Nielsen Rosenkrandtz and eventually, having become so very tired of him, she declared in court that she would now marry any scoundrel in the country so as to have someone who could help her against him. After the court sitting he rode so fast that he caught up with her and followed her into the hall and proposed to her with the words:

“You know you cannot find anyone worse than me, you know better than anyone how long I have quarrelled with you and caused you tribulations, if you will take me now then our quarrel is settled. At that she said a sharp no, she would not have him, but in order to be left alone by him she would give him her eldest daughter, Miss Ingeborg Huide. To that he said no; he would not have her daughter, he would have her herself. She said that she was an old woman, she would not marry. So he stayed with her for three or four days and spoke such fine words to her that she promised she would take him. Then she said that she was 48 years of age, if they were to have children together then they should have a wedding soon. So they prepared a wedding that very year, and 40 weeks later she had a daughter, she was called Anne Rosenkrandtz, she lived until she was 12 years old.”

Sophie Brahe seldom adds personal comments to the information in her family history book, but when she does so it is always in connection with someone she has known.

The Swedish family book kept by Sigrid Bielke (1620-1679) at about the same time takes a different approach: her thoughts and feelings colour the family records. In 1643, when twenty-three years of age, Sigrid Bielke married Field Marshal Gustaf Horn. Horn, who was twenty-six years his wife’s senior, had a daughter called Agneta from his first marriage. In adult life Agneta Horn became known as a temperamental and strong-willed character; her autobiography paints a picture of the difficulties she had in getting on with her stepmother Sigrid Bielke.

Sigrid Bielke accounts in the customary manner for weddings, births and deaths in her own family and her husband’s family. The information is arranged annalistically; each entry begins with year and day of the month, followed by the name of the new-born baby or the deceased and then often by a formularised prayer. Like many seventeenth-century women, Sigrid Bielke had a baby nearly every year. Between 1644 and 1655 she had nine children, of whom only two reached adulthood.

“[On the 3rd of July 1654] my darling and beautiful little Gustaf Carl [died] after five days of illness, and then, adding to even greater sorrow, that same week on Friday the 7th of July, after three days of illness, our only sweet son Evert Horn, whom it has also pleased God to call to Him from this wicked world, at 4 o’clock in the afternoon. Both died in Riga, both of a disease of the blood. God make happy their fair and beautiful souls in His Kingdom and give them a joyous resurrection with all believing Christians, and comfort we now deeply grieving parents who have now had to live in such great sorrow […].”

Thus wrote Sigrid Bielke in her family book.

Sigrid Bielke limited her records to the closest family circle, as did many noblewomen in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries: they catalogued the most important events and dates in their own families. This interest in the family and the individual in that family led to the genres of autobiography and diary, both of which became increasingly common in the course of the 1700s. The interest in individual personalities would occasionally result in major historical study – as in the work of Sophie Brahe – but in such cases a number of special social and cultural conditions would have to be fulfilled. That the records also had legal significance is obvious. Family books contained facts that could be invoked in, for example, inheritance disputes.

Women were the main cataloguers of family data, and their writing skills were used to keep ongoing records of the family finances. In Metta Lillie’s diary for 1737-50 we can see how these financial and genealogical records merge into a more personal diary.

“On 23rd of August in the year 1661 my daughter Elsa Margreta came into the world here at Limbohålm. May God grant her to live a Christian life and die blessed.”

(Edla Hedvig Silfverstedt’s family book)

Friendship Albums in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries

In the mid-1700s, the friendship book experienced a new surge in popularity as an ingredient in the eighteenth-century cult of friendship. They were also occasionally called “album amicorum” or “philoteca”, meaning “book of friends” or “temple of friendship”, i.e. a meeting-place for friends, an album containing writings, paintings, drawings, and autographs collected from friends. During the eighteenth century this practice spread beyond the circles of young noblemen and students, and the number of friendship albums owned by women began to increase. These albums were of a slightly different composition, given that not many Nordic women were granted the chance to undertake study trips in Europe, and so their family circle and friends filled the books with notes, poems and good wishes. The custom of keeping a friendship album continued in the nineteenth century, now as poetry books and guest books.

The painter and singer Marianne Ehrenström, née Pollet (1773-1867), wrote her lengthy memoirs in French, extracts of which have been published. Marianne Pollet came from a Protestant family in Flanders, and during her childhood she lived in Zweibrücken, Germany, and Stralsund, Swedish Pommerania, where her father was Commandant. The family’s conversation languages were French and German. In 1792 she was appointed lady-in-waiting to King Gustaf III’s widow, Sophia Magdalena of Denmark; she remained at court, where her singing and piano-playing skills were greatly appreciated, until 1803 when she got married.

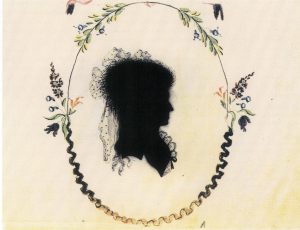

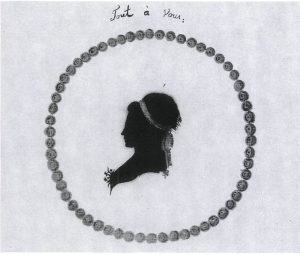

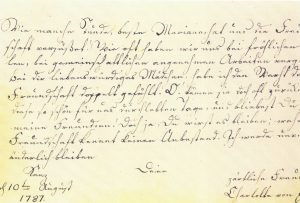

A small silk-bound friendship book survives from her young days in Stralsund; between 1785 and 1792 she had collected notes from family and friends, who were primarily from the Swedish and northern German nobility. Besides the written contributions, the book contains drawings and cut-out and painted portrait silhouettes. In 1787 her mother, Caroline de Pollet, wrote in the book: “How noble and moving is friendship when at its foundation lies the name of a mother and her daughter; and when the former can offer up her heart to her child as a mirror, true and never falsely flattering!” (translated from the French).

The book also contains a verse on friendship written by Duchess Hedvig Elisabeth Charlotta at about the same time, in Stockholm, and sent to her friend Countess Sophie Piper: “For corrupted hearts, friendship is not made. / O, divine friendship! Consummate bliss! / The only excitement of the soul in which exaggeration is allowed […].” (translated from the French).

A delightful little painting, executed by Marianne Pollet herself, shows a young woman walking between rose bushes towards a temple devoted to friendship. Neither time nor distance can efface you from my heart, another friend ensures her in rhyming French. The men’s voices are also heard, and they have quite a lot to say about the demands made of women’s charms, naturalness and intelligence – although the women were not permitted to be ‘learned’. In 1792 Charles Fredric Boye wrote in the album:

Être femme sans jalousie,

Et belle sans coquetterie,

Bien juger sans beaucoup savoir,

Et bien parler sans le vouloir;

Ni familière ni hautaine,

Exempte d’inégalité:

C’est Votre portrait même

Il n’est ni fini ni flatté.

Being woman without jealousy,

And beautiful without coquetry,

To judge well without extravagant knowledge,

To speak well without so willing;

Neither familiar nor haughty,

Free from inequality:

That is the very portrait of you

Neither finished nor flattering.

Lund University Library also has two small friendship albums owned by women in the early nineteenth century. One belonged to Magdalena Gyllenkrok (1788-1862), with notes and drawings dated to 1814-19. ‘La Tendre Amitié’ (tender friendship) was still the major topic, but of the maxims approximately one third were now written in Swedish, while the rest were in French and German.

In Carin Wulff’s (1806-1857) friendship album nearly all the verses – the book consists mostly of verses – are written in Swedish. Most were written in the mid-1820s and wish good fortune, happiness, virtuousness and love for the young owner of the book. It seems that most of the entries were written by her friends, from the bourgeoisie and of her own age, and some of them have sewn a lock of hair next to their signature. The book has much in common with the poetry books of a later era.

In Carin Wulff’s friendship album from 1828, we read:

Be like your mother in virtue and conduct,

Fully but covet no more than this,

And you shall become a credit to women,

As now you are a jewel among girls.

Although the collection in Lund University Library is small, a clear tendency emerges: during the nineteenth century the aristocratic custom of the friendship book was taken up by the bourgeoisie and, simultaneously, the language used moved from French and German to Swedish.

The friendship albums and family history books might also manifest a pattern clearly indicating some gender differences. The seventeenth-century friendship albums primarily reflect the men’s travels, their journeys out into a Europe of scholarship and warfare. This sheds light on the individual breaking free from the family circle in encountering new places and new people. The women focus on genealogy, parents, husband, siblings, and children. They reflect life and death in their own family, the network that ties them to the past and to the future, and in which they themselves, through their many children, or alternatively their childlessness, constitute an important unifying junction.

Translated by Gaye Kynoch