The view taken by the Christian Church of women who speak and write on holy matters has naturally changed over the course of time. As in other areas of society, we see the Church giving women wide scope for activity at the beginning of a movement, during periods of expansion and development, whereas prohibitions and restrictions increase in step with institutionalisation and consolidation. This has principally applied to women who have wanted to speak and write about God; it has been less applicable to those who have sought other, more active roles in the Church; for example, that of minister and agent of the sacraments. Church opposition to women assuming this role has always been – and is still – intense. Attitudes to women who have evangelised, preached, prophesised or in other ways acted as God’s mouthpiece have, on the other hand, been inconstant: at times accepting, at times non-committal. Opinions have been determined by the Church’s need for messengers and by pressure exerted on the Church by various interest groups. We can identify four periods of relative latitude as regards these speaking and writing women. The following time-spans are of course flexible, depending on the area of Christian Europe under consideration. First, the period preceding the official establishment of an organised Church (c. second century AD); secondly, the expansion of the Church in Europe during the seventh to ninth centuries; thirdly, lay Pietism of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries; and fourthly, the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Pietist movements in the wake of Reformation and Counter Reformation. The Jesus of the Gospels is exceptionally open-minded when it comes to women. He broke both with Jewish and with Roman views of women’s role in society – he treated women as his equals. No words spoken by Jesus suggest a perception of women as inferior to men. Mary sat at Jesus’ feet and listened to his teachings, and he said that she, as opposed to Martha who was left with the serving, had chosen the good part. Apart from Jesus’ favourite disciple, John, women were the witnesses to his death on the Cross, and women discovered the empty tomb. It is clear from the Acts of the Apostles and from the Epistles that women played a prominent role as teachers and missionaries – for example, in the Epistle of Saint Paul the Apostle to the Romans, Paul mentions thirty-six colleagues, of whom sixteen are female. He taught alongside Priscilla in Corinth. The reaction of the established Church to female apostles can be seen from its rejection of the story of Thecla of Iconium, a woman reported to have worked with Saint Paul. The Gnostic-influenced groupings had different priorities: here women were permitted to act as priests.

Once the Church had decided that it was a male prerogative to preach and administer the sacraments, the only options open to the woman who sought active and dedicated religious commitment were martyrdom or monastery. Many Christians considered the growing institutionalisation of the Church to be a deviation from actual Christianity, which they thought should be without hierarchies and should be based on a life of simplicity and the renunciation of worldly things. The monasteries were in part a result of this outlook, and when Christianity was elevated to the status of state religion in the fourth century, monasticism gained momentum. Convents for female monastics were set up at about the same time as the first monasteries for communities of monks.

Growth in the cultural significance of the convents is mainly observable between the seventh and tenth centuries, and primarily in France, Germany, and Britain. It has been estimated that in the eighth century there were more than twenty convents in Britain, and more than twenty in France and Belgium, and that in the ninth century there were eleven convents in Saxony. They were led by powerful Abbesses, whose influence was not least due to the extensive lands attached to the convents. Roswitha von Gandersheim (c. 930-c. 990) has become known for her learning and her writings: she wrote legends, plays, poetry and epic works in Latin.

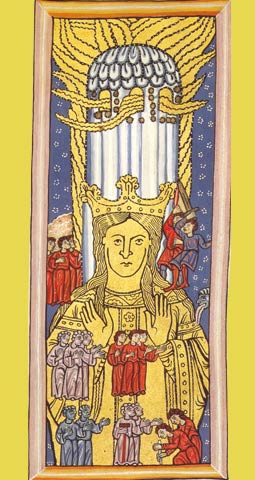

Hildegard von Bingen (1098-1179) was one of these authoritative abbesses, even though she does not fit in with the four periods noted earlier: she founded a convent at Rupertsberg and was known and respected by bishops and popes for her erudition and her visions. She gathered the revelations sent to her by God in a work entitled Scivias (1141-1151). The title should be read as: Scito Vias Domini, that is, Know the Ways of the Lord. Scivias is an expansive work: it tells of the creation, redemption and the last judgement in vibrant colours and with precise, sometimes naturalistic, details. At the behest of the Pope, in 1148 the Synod of Trier confirmed that Hildegard’s visions were divinely inspired, and that she had prophetic powers; male endorsement was essential.

The first convents in the Nordic region were established in the twelfth century, when a number of the most well-known nunneries were founded: Vreta and Gudhem in Sweden, Bosjö and Börringe in the then-Danish area of Scania in what is now southern Sweden, and Nonneseter in Norway. Birgittine convents were founded during the fifteenth century: Vadstena in Sweden, Naantali in Finland, Mariager and Maribo in Denmark; all convents with major cultural and political influence. The founder of the Birgittine order, Birgitta, was not unlike the great abbesses of earlier centuries, particularly Hildegard von Bingen.

Hildegard von Bingen saw the Holy Spirit at work throughout the cosmos. The Holy Spirit as the life-giving force of love shines especially brightly in the Virgin Mary, here extolled:

O most noble greenness,

you are rooted in the sun,

and you shine in bright serenity

in a sphere

no earthly eminence

attains.

You are enfolded

in the embraces of divine

ministries.

You blush like the dawn

and burn like a flame of the sun.

The days of the grand abbesses eventually drew to a close. This was partly due to the devastating advances of Vikings and Arabs in the ninth, tenth and eleventh centuries, partly because from the eleventh century onwards the Church tightened its grip on the monastic orders. At the beginning of the thirteenth century, Pope Innocent III found reason to order the suppression of certain abbess activities: giving blessings to their nuns, hearing their confessions, reading the Gospel and preaching publicly. A third contributory factor to the curtailment of the abbesses’ power was that the eleventh century saw the beginnings of a shift in the axis of religious life: from the rural areas, where the convents were active, to the urban areas, where the cathedrals and churches with their ministers now fashioned the basis for the twelfth- and thirteenth-century upsurge of lay Pietism. The growth of cathedral schools and universities gradually led to the learned culture becoming a powerful factor. This process cannot be said to have been of benefit to the women, at least not those with a mind set on scholarship and writing.

On the other hand, women took part in the emergence of the new spiritual movements, each of which displayed distinctive characteristics: emotional and figurative language (Cistercians); concentration on the motions of the innermost soul (Neoplatonic mysticism); a will to serve thy neighbour in close contact with the secular world (Franciscans). During these and the succeeding centuries, large numbers of women flocked to the movements that operated within the parameters of what was permitted (Beguines, Franciscans) or beyond these permissible limits (Cathars, Waldensians, Lollards).

Cathars – from Greek katharos (pure). Heretical movement in twelfth-century France. Cathar belief was dualistic, and the route to salvation was exclusively by means of ascetic renunciation.

Waldensians – followers of Pierre Valdès (twelfth century, later known as Peter Waldo). Sect originating in Lyon. Banned from unauthorised preaching in 1179. Expelled as heretics from Lyon. They espoused strong moralism and intense study of the Bible. They rejected Church hierarchy and teachings on the sacraments.

Lollards – from Middle Dutch lollaert (mumbler). Strongly anticlerical movement, originated in the writings of John Wyclif (c. 1324-1384) in fourteenth-century England. Believing in obedience to the “law of Christ”, they demanded social and economic reforms. Bible study was central to their lives, which were devoted to piety.

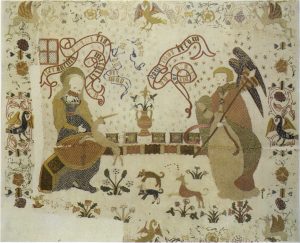

The Beguinal movement was a sisterhood consisting of pious women who moved into a beguinage – a community, often within a walled enclosure – where they led ascetic lives of religious devotion without actually joining a religious order or being under any direct ecclesiastical control. They supported themselves by means of, for example, fine needlecraft – the famous Belgian lace might have originated in the hands of Belgian Beguines. They were happy to set up their beguinage close to an already established convent: in Vadstena, for example, there was a beguinage just outside the convent wall. In 1228, following a measure of opposition from the Church, the Beguinal movement was finally approved, and it was often Dominican friars who were entrusted with giving the Beguines pastoral support in the form of sacraments and sermons. Beguinal communities were mainly to be found in what are today Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany and Switzerland. Christiana of Stommelen (1242-1312), known in the annals of Swedish literature through a biography of her written by the Dominican Petrus de Dacia (c. 1230 – 1289), was a Beguine in Cologne.

This is the age of the foremost female mystics, women such as Mechtild of Magdeburg (1212-c. 1282, a Beguine and later a Cistercian nun), Mechtild of Hackeborn (c. 1241-1299, a Cistercian nun), and Gertrud of Helfta (1256-1302, a Cistercian nun). Mechtild of Magdeburg first joined the Beguine order of nuns in Magdeburg, but the Beguines’ vulnerable status meant that she had no institutional support and thus eventually had to seek shelter in the powerful convent of Helfta. In her case, we can see the conditions under which these women worked: without clerical and/or political backing, their visions could be classified as heresy. Saint Birgitta, on the other hand, did not lack this backing: her father confessors and her connections with the Swedish royal court, coupled with her own high social rank, gave her a good foundation from which to be taken seriously.

Religious enthusiasm of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries had its consequences. The Church tried to control the various religious movements, and the position taken on lay Pietism hardened. In 1215 the Fourth Lateran Council approved the dogma of transubstantiation – the transformation of the bread and wine of the Eucharist into the body and blood of Christ – which strengthened the authority of the priest. Annual confession was made mandatory. The establishment of new religious orders was forbidden, making it possible to curb the inclination to independence displayed by the new movements. In addition, a procedure of inquisition was established, which condemned Cathars, among others, as heretics. In some respects, Birgitta was a casualty of this reaction by the Church, because her Birgittine convents never amounted to an actual independent order, but remained a branch of the Augustinian order. In 1293 a papal bull, Periculoso, stipulated how a nun should live, while yet again confirming women’s weakness and their status as a danger to themselves and to men. It was also stipulated that the Church alone could rule on whether or not a vision was of divine origin. The Council of Vienne, 1312, called for a ban on the Beguine movement, referring to heresy of a mystic-pantheistic nature thriving among the Beguines.

The Reformation can be seen as a continuation of the medieval, more or less heretic, movements within the Church. Generally speaking, throughout Europe both the Reformation and the Counter Reformation called for the services of women. In the Nordic countries, however, women played no prominent role in the Reformation, one reason undoubtedly being that their low profile was prescribed from on high. In Sweden, the Reformation was implemented relatively quickly and painlessly, and can probably be called firmly established with the decision taken at the Convention of Uppsala to adopt the Augsburg Confession. There was one way in which the Reformation led to a regrettable change in circumstances for women with scholarly or literary ambitions: the convents vanished. The female section of wealthy, politically and culturally influential, Vadstena closed in 1595; the Finnish Naantali was converted into a church in 1584; and the Danish Birgittine convents Maribo and Mariager were converted into convents for unmarried noblewomen in 1621 and 1588 respectively. There was, nonetheless, a way in which the Reformation was an improvement for women: it boosted their chances of learning to read – the reading consisted of Bible, hymn book and catechism. Women might be assigned to supervise those below them in studying the pure Word of God. The many seventeenth- and eighteenth-century hymns penned by women also show that reading skills could lead to writing skills, that reading could lead to translation and hymn writing.

The sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth centuries represent the promised age of sects in European ecclesiastical history, the dates naturally subject to country or area of Europe. Women – in exactly the same way as in the early Church and High Middle Ages – played prominent roles within the sects. The exemplar was the early Church era in which there was no priesthood and in which Christian life was thought to have been characterised by strong, subjective piety; by simple and virtuous conduct. There was a revival in the religious terminology of medieval mysticism, particularly the emotional language of bridal theology and Cross piety. Another distinctive feature of the movement was the importance placed on the radical change of perception known as conversion. Autobiography was a frequently used forum in which to highlight the experience of conversion and to tell about the wonderful grace of God in respect of the wretched sinner. Pietism and Herrnhutism travelled from Germany to the Nordic countries. The movement attracted women from all social classes, although at first, during the second half of the seventeenth century, perhaps mainly those from the upper social strata. Towards the end of the period, during the first half of the eighteenth century, women from the very lowest strata could turn, for example, to radical Pietism, one of the characteristics of which was enmity towards the Church, and to Herrnhutism.

No hymn, prayer or autobiography written by a female adherent of the piety advocated by Arndt, Pietism or Herrnhutism would have been perceived by the writer as subjective in the sense of being written to show off the subject. It was more a case of God being revealed in the subject: God at work in the individual. These women, too, saw themselves primarily as God’s mouthpiece.

Johann Arndt (1555-1621), Lutheran writer of devotional Christianity, was strongly influenced by medieval mysticism. His Vier Bücher vom Wahren Christentum (Four Books on True Christianity) had most impact on the religiosity that emerged with Pietism.

Similarly, like their medieval predecessors, these women had to concede that they were the weaker sex – their writings teem with self-derogatory comments – and they had to realise that they were an instrument of God’s will, just as they had to abide by their male leaders’ idea of good theology. An active woman in a sect – be she preacher or writer or both – almost always had a man at her side. For example: Margaret Fell (1614-1702, Quaker) had the leader of the Quaker movement, George Fox, as her support, and he later became her husband; the learned Anna Maria Schurman (1607-1678, Labadist) stood alongside the founder of the sect, Jean de Labadie; Johanna Eleonora Petersen, née Merlau (1644-1724, radical Pietist) was married to a leading figure in the Pietist movement, Johann Wilhelm Petersen; Anna Nitschmann, a true leading light of Herrnhutism (d. 1758), stood at Zinzendorf’s side and later became his second wife. The only woman to have established and led a sect on her own would seem to be the prominent figure of theosophy, Jane Lead (1624-1704). She was the founder of the Philadelphian Society in North America, which was in turn the model for Zinzendorf’s Herrnhuter community.

Quaker – from English ‘quake’, tremble – or Religious Society of Friends. Originated in seventeenth-century England as a breakaway movement from Puritanism. Characterised by a plain worship style, pacifism and highly moral conduct. The doctrine of “inner light” is a concept of personal and direct experience of Christ. The intention of a Quaker meeting is collectively – in silence – to strengthen this connection.

Labadists – followers of Jean de Labadie (1610-74), critic of the Reformed Church, mystic, active in the Netherlands. Labadie’s thesis, based on the idea that the true Church could only accept the truly committed or “elect”, had great impact on later Pietist movements within Lutheranism.

As far as Nordic women in the Pietistic movements associated with mysticism, Pietism or Herrnhutism are concerned, it can be said that these movements gave the women a forum, a voice. From a religious perspective, their experiences were just as valid as those of the men, but the scope of their contributions was more restricted. The Norwegian Dorothe Engelbretsdatter and some of the Danish hymn writers were probably the only ones to breach the restrictions of their times and situation.

In the Name of the Father – and the Woman

Now and then the Church has permitted women to speak in their own name. Does this mean they have spoken as themselves or as God? The question may be posed in this manner given that women have, on the whole, spoken about what they have seen, what they have heard, and what they have experienced in the outer world and in their inner worlds. Was the Church in reality allowing women to tell about themselves in their own names? In order to address these questions we must first look at how the history of ideas perceives the concept of ‘I’ in medieval theology and in Pietism.

Medieval theology did not talk of the ‘self’ in our understanding of the autonomous, creative, individual, self-stimulating ‘I’. The contemporaneous concept was that of the soul, which was largely identical for all humankind. What differentiated souls was the degree of sinfulness – or of holiness, for that matter – that is, the degree of correspondence between body and soul.

In his Confessions (c. 380), Saint Augustine is much exercised by the nature of the soul. Augustine considers the soul to be the same as the self, and he sees this self as the life-giving, organising, willing and feeling force of the mental apparatus. Sense perceptions and the workings of memory are separate from the soul. God is not found in the soul, but He nonetheless resides within Augustine’s inmost self, where a constant battle is fought in the free choice of the will between desire directed towards good and desire directed towards evil. This battle between good and evil is particularly dramatic for women, since general opinion held that the woman’s soul might indeed be of the same category as the man’s, but that it was weaker and worse than his. The Church models of female life were the extreme points on the scale running from divine to mortal: the virgin and the whore (later, the witch). Augustine interpreted the Genesis story of the Fall as a story about how humankind was thereafter made corrupt. Corruption is the weakness of the will caused by sexual desire, and this corruption is transmitted down through the generations by means of sexual intercourse.

Sexuality was therefore wicked. The woman was seen as a gateway to corruption and, given the weakness of her soul, she had a greater facility for evil – went the theory.

It is not hard to distinguish the fear of subjugation behind this fixation, the feeling of powerlessness that was occasioned by sexuality.

Female sexuality was equated with female power. The essence of the witch trials is a manifestation of this fear. The Church offered women roles, patterns, not the personal development of a unique self. A striking feature of the dialogues, or interrogations, with inquisitor and judge, in which witches in the Middle Ages and the centuries following the Reformation were forced to play a part, is that the most literary, most artificial role is the one associated with sexual matters. Telling about their sexual debauchery with the devil, the accused women speak with the voice of “The Witch Hammer” (Malleus maleficarum, 1487). It should be pointed out in this context that the dismissive attitude of the early Christians towards family, towards the roles of the wife and mother, and their recognition of the role of virgin, was not an expression of hostility towards sexuality, but an expression of the circumstance that, while waiting for the impending realisation of the Kingdom of God, they had neither time nor energy for family life: for working, begetting and bringing up children.

The exact opposites of corrupt will, submission to the body, and base desire are found incarnated in the role of virgin as represented by, among others, the Virgin Mary. The role of virgin is highlighted in legends and hagiographies, and the choice of this role is glorified. The Virgin Mary chooses to obey God; virgins in the stories of the saints choose not to follow the route of marriage and sexuality. The beautiful words of a Danish Marian song – “Hil dig, Maria, den skinnende lilje, du fødte din signede søn med vilje” (Hail Mary, the shining lily, you willingly bore your blessed son) – are highly theologically charged.

It is paradoxical that Mary actually attests to her role as woman by giving birth to and rearing a child. Much later, this paradox led to the dogma of the Immaculate Conception. It should be noted that the most active period of Marian poetry, the twelfth century onwards, denoted a break with the earlier image of Mary as the Queen of Heaven and mistress of the angels. The emotional religious language of the twelfth century, trying in a variety of ways to turn the divine into the human, is a striking feature of Marian texts in the High Middle Ages. Even God and Christ are depicted in terms that emphasise their maternalness. The Cistercians in particular – for example, Bernard of Clairvaux (d. 1153), Guerric of Igny (d. 1175) and Aelred of Rievaulx (d. 1167) – described Jesus as a mother who gives birth and who nourishes. In describing the union of the soul with Christ, Guerric wrote:

“He is the cleft rock … do not fly only to him but into him. … For in his loving kindness and his compassion he opened his side in order that the blood of the wound might give you life, the warmth of his body revive you, the breath of his heart flow into you.… There you will lie hidden in safety .… There you will certainly not freeze, since in the bowels of Christ charity does not grow cold.”

In one of Aelred’s texts, Jesus has the characteristics of a breastfeeding mother, blood is changed to wine, and water is changed to milk: “Then one of the soldiers opened his side with a lance and there came forth blood and water. Hasten, linger not, eat the honeycomb with your honey, drink your wine with your milk. The blood is changed into wine to gladden you, the water into milk to nourish you. From the rock streams have flowed for you, wounds have been made in his limbs, holes in the wall of his body, in which, like a dove, you may hide while you kiss them one by one. Your lips, stained with his blood, will become like a scarlet ribbon and your word sweet.”

The rock mentioned in both texts is the Old Testament rock split open when Moses smote it with his rod, and from which then flowed life-giving water. This rock prefigured Christ, and is often used to symbolise him. The crack in the rock is here – as is often the case in Christian tradition – equated with the wound in the side of the body of Christ. The water and the blood that stream from this wound are, among other things, symbolic of the divine grace dispensed in the bread and wine of the Eucharist. As regards the maternal imagery, it should be noted that in medieval physiological thinking milk was transfigured blood. Thus, the mother nourished her infant with her blood. The pelican, believed to nourish her young with blood drawn from her own chest, became a symbol of Christ.

There was altogether a feminisation of religious language during this period. Bridal mysticism’s erotic images of the union between soul and Christ are well known from, for example, the Nordic hymn tradition; the image of the tender, maternal Mary rather than the nobly sublime Queen of Heaven is another element of this feminisation. The term ‘feminisation’ implies that the language is emotional, that it speaks more to feeling than to reason. The religious language employed in earlier centuries had placed emphasis on God as king and judge, as elevated above the human sphere. Original sin, the Fall and atonement had been at the crux of religious thought. Creation and incarnation now become the focal point. The human being moves closer to God, is perceived as being made in God’s image, and Christ is the guarantee that the human being is inextricably linked with God. Whether this approach to God under a female aspect should be read as a manifestation of increased respect for women, or for women’s increased scope in the ecclesiastical forum, seems uncertain.

Saint Birgitta, who was herself a mother, is also representative of this tendency. In 1371 she wrote to the Spanish nobleman Gomez de Albornoz:

“I counsel you, my dear son, often to confess your sins, and if at times you feel the desire to take Holy Communion, then receive willingly and humbly the Body of Christ. For, just as the infant is nourished and grows by a mother’s milk, so too shall your soul by receiving the nourishment of the Body of Christ be strengthened and grow, thus better to receive and sustain the divine love.”

Birgitta’s wonder at the miracle of Jesus’ birth is a mother’s amazement that something like that can happen so easily and without pain, and it also highlights the marvel of incarnation:

“Whilst she [i.e. Mary] was thus absorbed in prayer, I saw the child quicken in her womb, and at the same moment, yes, in an instant, she gave birth to her son.”

Saint Birgitta shaped her life according to the model provided by the lives of the saints and Marian legends. Birgitta’s life, as it was reported in stories about her, was later a model for, among others, the English visionary Margery Kempe (c. 1373-c. 1440). Saint Birgitta’s monastic Rule, the Order of the Most Holy Saviour, has the same basic tenet as all other monastic orders: that one can shape one’s life and one’s self.

The Church never acknowledged Margery Kempe as a mystic, possibly because she did not have clerical backing, possibly also because she was married when she had her visions – what is more, she had just had a baby. Her first vision is linked with the fear of death she experienced upon the birth of her first child. Her terror of death and damnation led her to go to confession, but this only made matters worse because the father confessor had reproached her in strong terms:

“And anoon, for dreed sche had of dampnacyon on the to syde and hys [i.e. her confessor] scharp reprevyng on that other syde, this creatur [i.e. Margery] went owt of hir mende and was wondyrlye vexid and labowryd wyth spyritys half yer eight wekys and odde days.” Margery’s lengthy account of her experiences, The Book of Margery Kempe (c. 1436-38), reads more like a biography than a report of mystic incidents. She refers to herself as “her”, “she” and sometimes “this creature”.

If women did have weaker souls than men, then how could the Church concede in theory that women could also disseminate knowledge of God? This question leads straight into one of the most interesting discussions of the High Middle Ages: in which part of the human psyche did God move? The issue of what happened to a person when they were converted, when they heard voices or saw visions, had been a subject of deliberation ever since the time of Augustine and the other Church Fathers. The mind came under scrutiny.

The Franciscan Bonaventure (1221-1274) summed up the three journeys to knowledge of God, the three aspects of theology:

“Per symbolicam recte utamur sensibilibus, per propriam recte utamur intelligibilibus, per mysticam rapiamur ad supermenta-les excessus” (the symbolic, the proper, and the mystical, so that through the symbolic we rightly use the sensible, through the proper we rightly use the intelligible, through the mystical we be rapt to super-mental excesses).

The symbolic approach seeks God in nature, the intellectual approach seeks Him in the Scriptures and ecclesiastical tradition, and the mystical approach seeks Him in spontaneous, subjective activity of the mind.

This was the theoretical sanction for the mystics. The base from which it developed was, among other things, the theory of “scintilla animæ”, the spark of the soul, often also called synderesis, which, despite the original sin and the will to do evil, was nonetheless to be found somewhere in the depths of the soul, this being a meeting place for God and human. And this is where the process that could lead to the obliteration of the old person might begin. This inner essence should not be confused with our understanding of the ‘self’ in the sense of a unique, individual ‘I’. The inner person – “homo interior” or “se ipsum” – of which the medieval philosophers spoke, was found in everyone and therein lay the route to God. The objective of this personal evolution was not to become one’s self, but to be in God’s image, to be the human being Adam was before original sin and the Fall. This process could develop from one’s inner knowledge of God.

These theories paved the way for women to enter the public forum of the Church – or perhaps it was the other way round: the theories legitimised the experiences undergone by the many female visionaries and mystics, experiences which could not be dismissed. In one of Saint Birgitta’s revelations, Christ says to Birgitta:

“And when at your husband’s death your soul was greatly shaken with disturbance, then the spark of my love – which lay, as it were, hidden and enclosed – began to go forth […].”

This was an expression of the Augustinian premise that in the very depths of the mental apparatus there is the prospect of a new person, a transformed soul.

Medieval theory was also current in the Protestant movements. The Pietists and Herrnhuters adopted much medieval mysticism as their own, particularly the notions of the inner human and das Seelenfünklein (the little spark of the soul). Many Protestants – for the most part those who had been deeply influenced by Calvinism, for example the Pietists – considered ‘I believe’ to be the burning issue. Self-analysis and soul-searching therefore took on immense significance for Pietism and Herrnhutism.

The third approach alone led to certainty: it was only in one’s inner being that God could be found. The consequence of this was a tremendous intensification of the self, because God was no longer sought in extraordinary mental states, but was seen and felt via normal emotions and phenomena such as strong passions or dreams. In secularised form, the theory of God at the core of humankind was transformed into the theory of the divine in the human. The human mission was to realise the divine self, to form oneself, as it came to be known, according to one’s purpose, according to what was one’s actual purpose. The spark became a metaphor for the unique, individual, here-and-now objective of the journey. God could thus be omitted from the equation. What remained was the brilliant, divine human being – the man.

Stoic doctrine conceived of a centre to the human soul, a ruling principle facilitating the meeting of human and divine: hegemonikon – a spark of the original cosmic flame and the first of all motive powers. The transfer of this concept to Christian thought was initiated by Origin (c. 185-c. 254), who saw this principle as an organ of knowledge of God, part of Logos, the point where God and human meet. Saint Jerome (c. 340-c. 420), who translated the Bible into Latin, used the term “synderesis” in his biblical commentary on the prophet Ezekiel’s enigmatic vision (Ezekiel, chapters 1 and 10), in which he sees four living creatures – cherubim – each with four faces: of a man, a lion, an ox and, an eagle. Jerome interpreted these as four parts of the soul, with the fourth being “synderesis”, the spark of conscience. This led to the later idea of an element in the soul as the place for the meeting with God, as an organ of knowledge of God, as the indelible conscience. Christian theology needed a notion that captured and explained conversion, visions and the like. Augustine did not use the word directly, but he addressed the issue of what is indestructibly good in humankind; the extent to which the individual contributes personally to the process leading to God. In medieval mysticism, above all in the thinking of Eckehart (c. 1260 – 1327), the idea of “synderesis” – das Seelenfünklein – was central.

The medieval Church thus paved the way for women and their knowledge of God, but not in such a way that they could assume any kind of office in the ecclesiastical institutions. They were conduits for God, and it was up to the Church to decide if the message came from God or from Satan. During the thirteenth century, as mentioned, rules were devised regarding how these endorsements or denunciations should be handled. The examination of the messages turned into veritable legal proceedings – be it a witch trial or process of canonisation – with the participation of witnesses, inquisitors and judges. In the Middle Ages, a key precondition for the acceptance of a woman as witness to God was that she was not actually a woman, which is to say that she did not lead a ‘natural’ life. Most of Birgitta’s revelations come to her when she is a young, unmarried girl, is living in celibacy or is a widow. Her successor, Margery Kempe, was never approved as a visionary, one reason being that she had visions whilst confined in childbirth. Protestant women also had difficulties in securing legitimisation of their religious utterances. Dorothe Engelbretsdatter had to disavow, in no uncertain terms, any form of ‘looseness’ in order to be accepted.

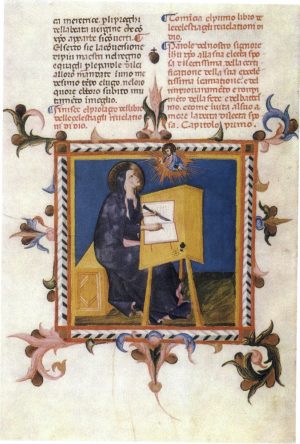

A clear insight into this way of thinking is found in Petrus Olavi’s (Petrus of Alvastra) version of Birgitta’s own account of what it felt like when the revelations appeared to her. The text was included in the Acts of Birgitta’s canonisation process: “For the witness reported that when he asked her now and then about the circumstances and vehicle of these visions, he himself could explicitly clarify and intelligibly describe them. For Fru Birgitta said herself […] that she saw and heard images and corporeal likenesses in her heart and perceived strange revelations in her mind and received wondrous assurances of the secret meaning of the visons and words that had been revealed to her. But in her heart she again felt a living being, as if a child were moving back and forth when she passionately prayed, and it moved more vigorously and ardently when she experienced greater incandescence and inspiration and less when the inspiration subsided. This movement in her heart was often so powerful that it could be seen and felt from the outside.”

This account gives the same curious and, for the High Middle Ages, typical mixture of the divine and the human as was current in the Marian texts and mystic visions. It is by virtue of this perspective, by virtue of the endorsement of women’s inner experiences, too, that we can actually become acquainted with Birgitta the woman through her revelations. However, a distinguishing feature of the texts is that the women’s ‘I’ is most clearly evident in dialogues with judges, Church officials, who will assess the women’s visions. Birgitta the person actually comes to life for us in biographical reports written by Magister Mathias and Petrus Olavi; and it is in the German mystic Mechtild of Magdeburg’s autobiographical comments – which form part of her visions, and address sceptics and slanderers – that we see the woman most clearly. The fact that an implicit or explicit accusation generates self-perception, an ‘I’, is apparent from the witch trials. Any actual dialogue has here been transformed into a monologue; the women’s voices are weak and frightened, and they take on the identity that the judges want to ascribe to them.

The judge with whom the Pietist and Herrnhuter women speak is what we might call a superego, that is, the conscience at its most accusatory and reproving. However, in dialogue with this superego the women show us their ‘I’ and their lives. They no more thought that they were describing their inner life for its own sake than did the medieval mystics. What they were actually doing was describing God; and as they were of the opinion that only living belief can beget living belief, the purpose of their autobiographies was to awaken belief in others, to evangelise and preach. Nor did the women hymn-writers see any contradiction between the personal and the public: the hymns combine biblical and mystical language with the subject’s tone of voice. In fact, the Herrnhuter women also interpret themselves according to established patterns – the religious autobiography can count its ancestors all the way back to Augustine.

The landscape of the soul portrayed in the medieval writers’ texts, and in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century writings influenced by mysticism, Pietism and Herrnhutism, is rooted in the theory of the split and alienated self or the split and alienated soul. The human soul is the object of a battle between good and evil, and the human is either on the way to heaven, the rightful home, or to hell, eternal alienation. This split is reflected in the vigorous fluctuation between extreme anxiety and euphoric ecstasy, between the depiction of Mary’s sorrow and Mary’s joy. Emotionalisation of the religious language is a common feature, and only a few of the texts exhibit a calmly reasoning abstract language.

It is in the emotional depths of the soul that we meet God and Satan. This is also where Augustine’s legacy is to be found; unlike the Neoplatonists and Stoics, he clearly linked desire with the ordinary human sphere, with love and passion. The truth about ourselves is found, according to Augustine, in our feelings. Complicated, tradition-bound images and symbols are the agency by means of which we try to capture the reality of experiences, albeit complex and difficult to describe. Depictions of heaven and hell are linked to depictions of ecstasies and states of anxiety. Saint Birgitta’s description of hell gives an idea of the terror of damnation:

“Then after that it seemed to the Bride [i.e. Birgitta’s soul] as if there had opened a fearful and dark place wherein there appeared a furnace all burning within; and that fire had nothing else to burn but fiends and living souls. And above that furnace appeared that soul whose judgment was just completed. The feet of the soul were fastened to the furnace, and the soul stood up like a person. […] The shape of the soul was fearful and marvelous. The fire of the furnace seemed to come up between the feet of the soul, as when water ascends up by pipes. And that fire ascended upon his head, and violently thrust him together; so much that the pores stood as veins running with burning fire. His ears seemed like smiths’ bellows which moved all his brain with continual blowing. His eyes seemed turned upside down and sunk in as if they were fastened to the back part of his head. His mouth was open and his tongue drawn out by his nostrils and hung down to his lips. His teeth were as iron nails fastened to his palate. […] The skin which seemed to be upon the soul seemed like the skin upon a body, and it was as a linen cloth all fouled with filth; which cloth was so cold that each one could see it tremble and shiver. And there came from it pus from a sore with corrupt blood, and so wicked a stench that it could not be compared to the worst stench in the world.”

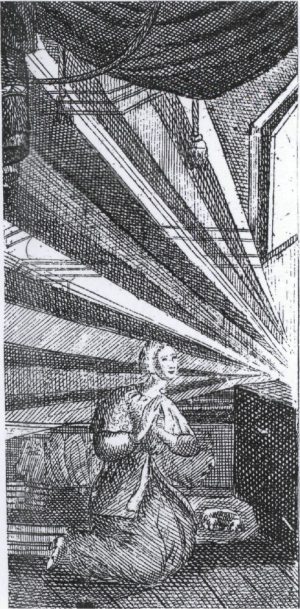

We can but ask from what depth Birgitta fetched these images. Birgitta and the medieval mystics depict the visions in pictures of another reality, detached from the viewing subject’s inner reality. Their heirs in a later era depict most visions as pictures of the inner soul: everything takes place in the sphere of feelings. This is seen clearly in an autobiography written by a Herrnhuter woman. Fear of damnation is, however, the same:

“[I] began to sing some verses, but just as I sit singing without tears so do my thoughts take me into the procedure of judgement as described in the Gospel on the Day of Judgement. I have to put the book aside and follow the musing I have received. I was then in my conscience led to the judgement, and there I had to attest with my name that I was damned and that not only for my evil deeds, but especially for all the grace shown me by the Lord.”

Seen from our perspective, this is the most paradoxical of experiences to be triggered by the image of the Cross of Christ. Graphic scenes of Christ’s Passion were evoked; pictures of Christ’s wounded and tormented body were a standard feature of these pious traditions: “Then his eyes seemed half-dead, his cheeks sunken, his face terribly disfigured, his mouth open, his tongue bloody; his stomach lay pressed flat against his back since all fluid was consumed, as if he had no entrails. His entire body was pale and languishing from loss of blood. His hands and feet were stretched tautly; they were utterly swathed in blood […] With death now approaching, and his heart exhausted by the fierceness of the torment, so all his limbs shuddered and his head lifted a little and then sank back down. His mouth seemed open and his tongue covered in blood.”

The experience of Christ on the Cross thereafter leads straight into the splendour of the mystic community. The mystic or Herrnhuter feels the love of Christ; is emotionally convinced of the grace of God and personal salvation. The language of piety of the Cross passes into the language of bridal mysticism, pain passes into pleasure.

These languages make no distinction between the word and the thing, the picture and the depicted, inasmuch as the boundaries between language and reality are erased in the mind of the one seeing or the one seeking. The experiences manifest no difference in time and space, nor any differentiation between ‘I’ and ‘you’ – the soul and Christ. The medieval women and their successors in later eras knew that their manner of expression was symbolic, but also that there was no other expressive option. They possibly also realised that they used everyday experiences to convey their insight and their message. Whatever the case, we cannot talk of repressed impulses in these texts, because desire is there for all to see. And, as they all knew, the language of desire and feelings is the language of truth. Whether or not these images and symbols, dreams and feelings, thus express the women’s ‘I’, their authentic inner selves, is another question. Religious convention offered them a language and a platform.

Translated by Gaye Kynoch