Often, the only collection of poems, indeed the only book, to be found in private homes, was the hymn-book. It provided comfort at bedtime – and not only to children and the bed-ridden. The hymns “Tryggare kan ingen vara” (Eng. tr. “Children of the Heavenly Father”) and “Blott en dag, ett ögonblick i sänder” (Eng. tr. “Day by Day and with Each Passing Moment”) belong to the everyday poetry of the Swedish people.

The poetry by Carolina (Lina) Sandell-Berg (1832-1903) has enjoyed incomparable success. In the period when she was writing, the patriarchy of the church, headed by Johan Olof Wallin, faced a serious challenge with regard to the composition of hymns and poems. Since Lina Sandell, there have been only two hymn writers of major importance in Sweden, namely Anders Frostenson (1906-2006) and Britt G. Hallqvist (1914-97). The hymn-books of the free-church communities came to be totally dominated by Lina Sandell, beginning with the first edition of Pilgrimsharpan (1861; The Pilgrim’s Harp). She took part in the editing of this collection herself, and fifty of the 225 songs come from her pen. Evangeliska Fosterlands-Stiftelsen (the National Evangelical Foundation) was the publisher of Pilgrimsharpan, which was printed in many editions and in 1889 was renamed Sionstoner (Songs of Zion).

With her roots in peasant society, Lina Sandell used down-to-earth, easily accessible language. This has made her much beloved, but it also made her spiteful adversaries, both in her own time and later on. As the best known among the Revivalist poets, Lina Sandell has unfairly been seen as a representative of a banal religious poetry and a cheap faith that avoid the deeper questions in life.

To be sure, there are sugary elements in her writings! A nursery-like harmony seduces the reader in “En stilla stund med Jesus, O vad den jämnar allt” (Sionstoner no. 383; A Silent Moment with Jesus, Oh, How It Smoothes Everything Out). But even in a hymn like this she writes about unbelief, about anxiety over little earthly concerns, and about the feelings one experiences upon leaving a Revivalist meeting, hurt and misunderstood. An anxious search for meaning and a half-secret doubt can always be detected in her poems. Lingering illness since her childhood contributed to the ever-present thoughts of death. The longing for wholeness and trust is generally stronger in Lina Sandell than the ability to believe. Maybe it is precisely her doubt and her familiarity with suffering that have made her so popular?

“But every time the Lord thus pulls up a planting, in whose shadow we have lied down, it is as if the view is at once expanded. We stand there so lonely in the open field without these visible supports to lean on; but at the same time the invisible home has become so much more real […]. The lighter the armour, the freer you travel”, Lina Sandell writes in her diary in October 1860, after the death of her mother.

To the editors of the hymn-books, her texts about doubt and yearning for death were offensive, and many of her hymns were therefore rewritten or discarded. A late example is the hymn that opens with the question, “Är det sant att Jesus är min broder” (Is It True that Jesus Is my Brother), which in 1986 was stripped of a stanza when it was selected for Den svenska psalmboken (The Swedish Hymn-Book). The following lines were expurgated: “Fast jag aldrig tror det som jag ville, Är dock sakan alltid lika sann” (Although I never believe as I would like to, nevertheless the truth of the matter is always equally so). After the modification, this anguished hymn was placed under the heading of “Comfort, assurance” (“Förtröstan, trygghet”)!

The fear of banality also results in the avoidance of all strong formulations. In the word list published by the Swedish Academy (Svenska Akademiens ordlista över svenska språket) the Swedish word “banal” is defined as ordinary, trite, and commonplace (“alldaglig, sliten, platt”). To what extent can we endure to read about people’s unrestrained feelings of happiness, love, or grief? The nineteenth-century person was able to endure this to a much greater extent than we are today. In the eyes of the committee that was set up in 1969 and that, in 1981, drew up its first proposal for an ecumenical hymn-book for use in Sweden, the following was too much:

O lär mig då älska, ja, älska dig så,

Att ingenting mera kan skilja oss två.

Du är ock för evigt densamme som nu,

Och ingen, nej ingen, mig älskat som du.

(Oh, teach me to love, yes, love You in such a way

That nothing can separate the two of us anymore.

You are and shall forever be the same as now,

And no one, really, no one has loved me as You do.)

This is the third stanza of the hymn “Jag älskar dig, Jesus, jag vet du är min” (Eng. orig. “My Jesus, I Love Thee, I Know Thou Art Mine”). Lina Sandell translated this hymn in the last year of her life, and in almost every line she addresses Jesus directly with the words ‘du’ (Thou) or ‘dig’ (Thee). The tension in the hymn is found in the comparison between earthly and heavenly love. To the observer, the love babble may appear unrestrained and tedious, if it were not for the rigour of the rhythm.

On the other hand, the adjustment of the words to the rhythm’s patterns is a sensual feature. This ‘banal’ hymn is definitely not plain, but rather all too ‘curvy’. The third stanza, quoted above, is the rhythmic and sensual climax of the hymn, but it was expurgated already when the first hymn-book proposal was drawn up. In the final report of 1985 the whole hymn was left out.

Lina Sandell’s images of God’s motherliness were particularly offensive to good taste. The censoring of her hymns constitutes a central part of the history of the Swedish hymn and Swedish religion, and it proves how important it has been, right up until today, to consolidate the male image of God. In 1972, the editors of Sionstoner followed the example of the Swedish state church and changed the words “Soothing like a mother” (“Hugsvalande såsom en moder”) to “Soothing in their hearts” (“Hugsvalande i deras hjärtan”), a line in the hymn “Tillkomme ditt rike” (Eng. tr. “O Father, Thy Kingdom Is Come Upon Earth”). Lina Sandell had borrowed this forbidden simile from the prophet Isaiah.

‘Mother’ is a word that has been the object of regular purges. Without destroying the rhyme, the Swedish word “moder” (mother) could easily be exchanged with “broder” (brother) – a more harmless word. “Kycklingmoder” (a brooding hen) became “fadershjärta” (a fatherly heart) and “modersvingen” (the motherly wing) became “fadershanden” (the fatherly hand). When the imagery in a hymn became too all-pervading, whole stanzas were deleted, or the hymn was removed when it was time for a new edition.

In both the Old and the New Testament, divine love and care are described as motherly. There, one also finds the earliest image of the hen protecting her chicks. Already in a prayer from the eleventh century, Archbishop Anselm of Canterbury called Jesus a mother, so this was far from being an example of Moravian (‘Herrnhuter’) heresy, as opponents from a later period believed. The Danish poet and pastor N. F. S. Grundtvig also employed the image in a hymn that Lina Sandell translated into Swedish. In the seventeenth century, the Norwegian Dorothe Engelbretsdatter had depicted, in even greater detail, the efforts of the hen to gather her chicks together. With nine children of her own, she knew what care involved.

When women stressed the traditionally female qualities of the divinity, they did not do this in order to replace the male God with a feminine one, but rather to clarify the abstract concept of God. They still called ‘Him’ by the name of “Father”. But by being endowed with motherliness, God acquired a milder demeanour and was no longer the formidable sovereign of the Old Testament, who demanded that fathers give the lives of their sons in sacrifice.

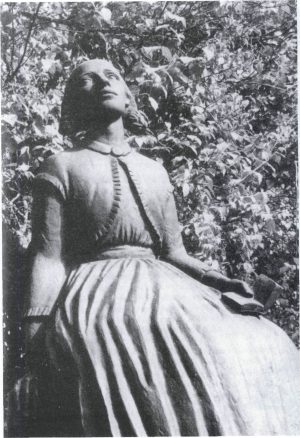

With the Revivalist movement’s comforting message of grace and atonement, a Jesus was created who lost his anger and rebelliousness. He is not the man who drives the traders out of the temple. Instead, he stands still with his hands stretched out to bless and shelter, like the statue of Christ made in 1821 by the Danish sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen and later mass-produced in plaster or porcelain copies for churches and private homes. By domesticating the image of the divinity and yet retaining its male gender, the female writers also communicated how they wanted men to be. Lina Sandell was not her mother’s but her father’s girl. As an adult, she had a male guardian angel, the district judge Th. Odencrants. He was the ‘girlfriend’ who shared her worry and doubt with regard to Oscar Berg’s marriage proposal, when she felt as if she had to choose between Jesus and Oscar. When the wedding had taken place, she wrote to Odencrants that Oscar arranged everything indoors for her in such a nice way, “with truly motherly care” (her italics). It looks as if, to Lina Sandell, the ideal human being was a motherly man, whereas a motherly woman would be too much of a good thing.

Jag kommer svag ock bräcklig,

Min kraft är otillräcklig!

Hvad är jag utom dig?

Jag kan ej hjertat böja

Jag kan ej själen höja

Om Du ej bor hos mig.

(I come feeble and frail, / my strength is insufficient! / What am I without you? / I cannot bend my heart, / I cannot elevate my soul, / if you do not dwell in me.)

Unpublished manuscript by Lina Sandell, sixteen years old.

Editors and publishers compelled Lina Sandell herself to change her hymns, and the censorship continued after her death. The hymn-book committee of 1980 described the popular hymn “Blott en dag, ett ögonblick i sänder” (Eng. tr. “Day by Day and with Each Passing Moment”) as “a song about trust in God’s fatherly care”, although they were well aware that the image of the father was not at all to be found in the original version of 1866. However, in 1872 “the Lord” had been replaced with “the Father”, and “the motherly heart” had been changed to “the fatherly heart”. Ironically enough, this happened in the same year as the publication in Swedish of the sermon “Guds moderliga hjerta och enkans oljokruka” (God’s Motherly Heart and the Widow’s Cruse of Oil; German orig. “Das Mutterherz Gottes”) by the idol of Lina Sandell’s youth, the German F. W. Krummacher, a sermon in which God is called “She”. There were, in other words, still rebels to be found.

While the masculinity of the image of God was challenged or defended, an uncontroversial feminisation of the angels was taking place. In the Bible and in the context of Christian art, angels had long been male. They were avengers with swords, serious messengers, or powerful guides. In the Baroque period, female angels begin to appear in art. In the popular oleographs of the nineteenth century, the guardian angels are often female. As God’s motherly envoys they hold their shielding hands over the children. In this way, by depicting the mild and protective figures – the messengers from God the Father – as women, the boundary between the sexes is upheld.

If nineteenth-century women could not become pastors and if they could not without conflict devote themselves to intellectual work, the closest they could come to the pulpit was by way of writing hymns. Lina Sandell called herself “a good scribe’s pen”, an expression that combines lack of pretence with high self-esteem. In fact, it was a problem for her to combine her inborn pride with suitable modesty.

“How come that great geniuses, and brilliant authors, are usually so free with their opinions and principles? One surely does not have any real use of a book like this, and still one reads it with pleasure! Can that be right!?!”, the sixteen-year-old Lina Sandell wonders in her diary after having read Goethe’s Wilhelm Meisters Lehrjahre, in which Book 6, “Die Bekenntnisse einer schönen Seele”, is based on a Moravian woman’s account of her rebellion against paternal authority.

The diaries from her teenage years bear witness to a terrible struggle to achieve female submissiveness and humility. The position she finally obtained as a full-time employee at the National Evangelical Foundation in Stockholm, with the task of writing poetry and prose as well as translating and editing journals for children and adults, offered more room for her preaching than she would ever have had as a pastor. She still dominates the hymn-books of the free-church communities. In the 1972 edition of Sionstoner, Lina Sandell is represented with seventy-six of the 700 songs, and the 1986 edition of Den svenska psalmboken (The Swedish Hymn-Book) includes thirteen of her original texts as well as one of her translations. Her first book, Andeliga vårblommor (1853; Spiritual Spring Flowers), was published anonymously. A few years later a journal editor gave her the signature ‘L. S.’. But the initials, which were supposed to be a screen that she could hide behind, became instead a standard. When her Samlada sångar (Collected Songs) began to appear in the 1880s, they were also published under this well-known signature.

In order to create a female tradition, the female Christian writers were looking for models among the figures of the Bible. Together with Charlotte af Tibell, Lina Sandell wrote the book Bibelns qvinnor (The Women of the Bible), and in 1882 Betty Ehrenborg-Posse chose the Bible’s Deborah, Miriam, and the four daughters of Philip the Evangelist as her models. These learned and poetical women, she thought, had been authorised by God to write spiritual songs, even though some might consider this task to pertain exclusively to the clergy.

If the young Carolina Sandell had not been so sickly, she would undoubtedly have had to follow in her mother’s footsteps as the hard-working wife of a pastor in some vicarage in the province of Småland, with cows and hens, maids and farmhands. Instead, she received from her father an uncommon education in languages, science, and geography. Her older brother, Johan, tried by every means to avoid becoming a pastor, but to no avail; Carolina, on the other hand, wanted to study.

Catharina Elisabeth (Betty) Ehrenborg-Posse (1818-80) came from a completely different background than Lina Sandell. Her father was the county governor of Skaraborg and died when Betty was only five years old. Her mother, Anna Fredrica Ehrenborg (1794-1873), taught her children never to let a day go by without their having increased their knowledge. In 1837, as a widow, she herself made her debut as a writer with a small prayer book, and afterwards she wrote little books for housewives as well as thick books of tales (under the signature of ‘Önämnd’, that is, ‘Unnamed’), children’s books, an account of a journey through Europe, and debate books, which among other things defended Swedenborgianism. Her daugher, Betty, made her debut four years after her mother with the collection of youthful poems, Små foglar från Kinnekulle (Little Birds of Kinnekulle).

When an older brother began to study in Uppsala, his sisters and mother moved along with him, and they began to frequently meet with Malla Silfverstolpe and the Knös, Geijer, and Atterbom families. Betty secretly studied philosophy at night, attended the lectures of Erik Gustaf Geijer and P. D. A. Atterbom, and provided her acquaintances with summaries of them.

Before 1873 women were not permitted to study at the universities in Sweden. Not until 1925 could women apply for professorships.

She earned her first salary as a governess, and it went to her mother’s sewing school for poor children. Little by little, teaching became a calling for her as well. Despite the school regulation of 1842, in the 1850s the public elementary school had not yet gained a firm footing. Betty Ehrenborg-Posse therefore gave classes not only in religion but also in general subjects at a voluntary Sunday school. After having attended a training college for female teachers in England, she devoted herself to the education of teachers. In fact, most of her literary production consists of educational prose and poetry. In the collections of her writings, the cheerful mood of the poetry competitions and charades of the Uppsala circles is combined with intellectual sarcasm. Betty Ehrenborg-Posse was critical towards the layman preachers, and in her letters she wrote ironically about the sombre young men who gathered together to read the works of Carl Olof Rosenius and sing the songs by Oscar Ahnfelt.

Carl Olof Rosenius preached a mild, forgiving Christian faith and was the publisher of the journal Pietisten (The Pietist). He was the spiritual guide and friend of Lina Sandell, whereas Betty Ehrenborg-Posse considered his doctrine inadequate. The composer Oscar Ahnfelt published twelve popular booklets with Andeliga sångar (Spiritual Songs) that comprised, among others, the melodies for a number of Lina Sandell’s texts.

As an adult, she is seldom as courageous and personal in her poetry as was the case in her melodramatic debut collection, which includes such role poems as “Sjelfmördarens dödssång” (The Death Song of the Suicide) and “Den Wansinniga om våren” (The Madwoman in the Spring). The latter poem is about a widow who, tormented by visions, imagines the maggot that “rejoices in the skullbones”. In her childhood home, the late father was a forbidden topic of conversation. She reserved her strongest expressions of self-criticism and religious struggle for her letters and diaries. It was difficult for her to forgive herself for an early attraction to Catholicism, and facing the prospect of marriage she was afraid that she would cause unhappiness because of her “unreliability”.

The severity with which she criticised herself is more conspicuous in her hymns than are the promises of grace and forgiveness. Her version of “När juldagsmorgon glimmar” (Eng. tr. “When Christmas Morn is Dawning”) is well known in Sweden, and school children sometimes still sing this song at the ceremony just before the Christmas holiday. They sing about the joy in the fact that God was willing to come down to earth to be born in a stable:

Nu ej i synd jag spille

Min barndomsdagar mer!

(Now I shall no longer waste / my childhood days in sin!)

On two occasions, Betty’s serious involvements with men caused a crisis in the family. It was not until she was thirty-eight years old that was she able to marry a man whose character and career her mother found acceptable, and at that point it was Betty herself who was reluctant. Just like her mother, Betty Ehrenborg-Posse was widowed while her children were young. Often she turns to God in the form of the Christ Child. Then she is able to draw on all her motherly sensuality:

O, kom i min famn! i mitt bröst sänk dig ner,

Låt mig älska och åskåda dig!

(Oh, come into my arms! Sink into my embrace, / let me love and behold You!)

– exclaims the single mother of three in “Barnet Jesus” (The Child Jesus) in Andeliga Sånger för Barn och Ungdom (1871; Spiritual Songs for Children and Young People).

She goes on, calling the Christ Child “my King, my Lamb” (“min Konung, mitt Lamm”); she nestles against Him and implores: “Light my life with Your spirit!” (“Med din Anda tänd lif uti mig!”). In the two final stanzas the symbiosis is complete. The narrator fills the place of the child, and the adult woman finds rest in the bosom of Jesus:

Du är idel kärlek, Du är idel tröst,

O, Du barn, sjelfwa godhetens brunn!

En springande källa går fram ur ditt bröst,

Som för ewigt hugswalar min mun.

War min, War min egen, war kostlig och kär,

War min himmel, min endaste fröjd!

Ditt sällskap förkorte den stund, jag går här,

I din famn är jag salig och nöjd.

(You are all love, You are all comfort, / O, You child, the very source of goodness! / A fountain flows from Your breast / which forever soothes my mouth.

Be mine, be my own, be dear and beloved, / be my heaven, my only joy! / May Your company shorten the while I walk here; / in Your bosom I am happy and content.)

The water of the fountain is a simple image of what human beings need. In the hymn “Morgon mellan fjällen” (Eng. tr. “Morn Amid the Mountains”), the water in the creek sings that God is good. In older hymns, Jesus’s life-giving flow is of a much more brutal and bodily kind. The flow and the fountain water are the blood from Jesus’s wounds. Through His martyrdom all Christians were to be saved and their sins forgiven. Betty Ehrenborg-Posse translated from English both “Klippa du som brast för mig” (Eng. orig. “Thou Rock that Burst Asunder”) and “Här en källa rinner” (Eng. orig. “There Is A Fountain Filled with Blood”), and when these hymns were revised in the twentieth century, the blood symbolism was toned down. The rock that burst asunder was the body of Jesus. Betty Ehrenborg-Posse writes:

[…] blodet, hwilket går

Från din stungna sidas sår,

Twage i sin himlasaft

Mig från syndens skuld och kraft!

([…] may the blood that flows / from the wound in Your pierced side, / rinse me in its heavenly juice / from the guilt and force of sin!)

In the Swedish Hymn-Book of 1937, what was concrete in the hymn has become abstract. Now the blood comes from the heart; Jesus is called “God’s Lamb”, which makes the image less dramatic; and there is no longer any ‘rinsing in heavenly juice’ to be found.

The fountain in “Här en källa rinner” is the blood of Emmanuel – that is, Jesus – with which we are to wash away the stains of sin in us. The author has the Swedish words “blod” (blood) and “god” (good) rhyme with each other. In the 1920 version, the blood is not mentioned at all, and the Swedish word that rhymes with “god” is “flod”, the fresh ‘flow’ of the fountain. In 1920 the human stains are no longer to be washed away. Instead, the water quenches the spiritual thirst. The heart is filled with peace and calm serenity.

The humidity found in Betty Ehrenborg-Posse’s hymns differs markedly from the sensuality found in the poetry of the childless Lina Sandell. As an adult Betty Ehrenborg-Posse writes, alarmed about her own sin and wickedness: “But o, Jesus, my blood-bridegroom, I throw myself with all my weight upon You” (“Men o Jesu, min Blodsbrudgumme, jag kastar mig med hela min tyngd på dig”).

Also Charlotte af Tibell (1820-1901) writes poems about how she throws herself into Jesus’s open arms when she is troubled. His blood gives her strength like the wine of happiness, and she “strolls in the Word with her good-hearted friend’ (“Lustvandrar i Ordet med vännen god”).

Compare with Lina Sandell’s hymn from 1880:

Herre, låt ingenting binda de vinger,

Hvilka du en gang har gifvit åt mig!

(O, Lord, don’t let anything bind the wings / that You once gave me!)

She is only able to express herself in this way after a struggle to gain faith in God’s grace. What we now call teenage problems, when children have to find their own place among the adults and decide about their own degree of conformity and rebellion, manifested itself in many nineteenth-century Swedish girls as a crisis of faith. As candidates for Confirmation they learned the rules, and at the church ceremony they were to profess their submission aloud before the congregation and the all-seeing God. Their diaries tell of their great anxiety prior to their Confirmation, which is no wonder since their pastors could admonish them in the manner of Lina Sandell’s father, Jonas Sandell:

“Do not commit a sin: you have God above you; His angel beside you; the evil enemy behind you; a thousand witnesses inside you; and the open abyss below you.”

The reports in the diaries of crises having to do with the consciousness of sin, whether it be insufficient or excessive (and in both cases equally distressing), constitute a separate genre that never reached the public, except in a tamed poetic version – and then as isolated hymn lines that were promptly softened by words of consolation. The prose of the diaries, on the contrary, is chaotic and not consolatory. These texts abound with underlinings, repetitions, corrections of sloppy errors, and exclamations, as well as both question and exclamation marks, now and then repeated as clear signs of distress.

“The Lord will continue to keep me in the oven. Oh, He certainly sees how much dross there is that still needs to be burnt away. He certainly sees how I still haven’t become nothing. Oh, if only, after so many death-blows, the flesh would really be destroyed”, Lina Sandell writes in her diary on 1 August 1860.

Charlotte af Tibell only began to publish as a poet after her conversion around the age of thirty. Blommor på vägen till Zion (1852; Flowers On the Road to Zion) is introduced by a programmatic statement in the form of the poem “Den fångne fågeln” (The Captured Bird). The bird is chained inside her breast and is not allowed to sing, “thus is it commanded”. The bird wants to sing about the questions of the heart but has to forget and put it all aside. Perhaps the notes will sound only after death, among the blessed harps at the throne of the Lamb. But there is a possibility at hand. The last stanza says that the tender voice may be heard on earth, if it sings God’s praise:

Hvar ton må öfverensstämma visst

Med Ordets predikan om Jesum Christ.

(But every tone must be in accordance / with the preaching of the Word about Jesus Christ.)

This is to be the solution for Charlotte af Tibell. Her preaching is in accordance with the orthodox doctrine, but in her debut collection of poems she also has her older, profane poems printed. The rebel Romantic discovers a suitable code for her emotions by referring to the kinship she feels with thunder. In the poem “Åskan” (The Thunderstorm), we read:

Höj din profetiska stämma,

låt henne rulla i skyn,

rista din varnande skrift,

klart uppå himmelens bryn.

(Raise your prophetic voice, / let it roll in the sky, / carve your warning writing, / clearly upon heaven’s brow.)

To be on the safe side, on another page she points to such plants as the linnaea and the cat’s-foot as her humble and content models.

In 1867 she publishes the second part of her collected poems. It had been a turbulent time in Europe. Prussia had taken Schleswig and Holstein from Denmark, and in Sweden opinion had been divided on the issue of military support. Austria had also been conquered by the Prussian army, and France was the next target. This is when Charlotte af Tibell writes about the Viking Age, about Frideborg, whom she calls “the first Christian woman in the land of our fathers”. In the poem, Frideborg is converted by Ansgar and turns to her brothers and relatives to entreat them to come to the Lord and no longer sacrifice to dumb idols: “Join, you band of giants, His league of peace!” (“Träd, kämpaskara, i Hans fridsförbund!”).

Charlotte af Tibell published her only novel, Esther och Castenza (Esther and Castenza), in 1872. The novel is a romantic story about two motherless girls and presents the vision of a utopian society where men and women work side by side and where love reigns supreme. However, a great part of the novel describes the men’s abuse of power and their arrogance. The criticism is presented with humour, but the message is meant in earnest. The men have to accept their responsibility – in other words, be Christianised.

Charlotte af Tibell dedicated her collection of poems to Princess Eugenie of Sweden, who regularly arranged sewing circle meetings at the Royal Palace in Stockholm. What the women actually were engaged in was discussion of religious issues, the planning of charity work, and Bible studies with invited teachers. Lina Sandell was also summoned there, by the princess herself.

Translated by Pernille Harsting