“And still, reading is, I think, what I like the most”, writes Louise Munthe, the daughter of a county governor, in her diary on 2 January 1860. In the course of the day she has spent some time reading Grace Aguilar’s novel Hemmet och hjertat (orig. Home Scenes and Heart Studies), and this has given her great pleasure. However, she is a well-mannered girl and is well aware of the establishment view on novel reading. And by a sort of inner compulsion she immediately begins to defend herself. “Sowing goes fine, if only I am allowed to invigorate myself with a bit of reading every now and then”, she writes and continues:

“People say, however, that it is not good for you to indulge in it too much. I think that this may be the case, because one sets aside other duties and other activities, but I find it difficult to understand that it should be harmful in any other way.”

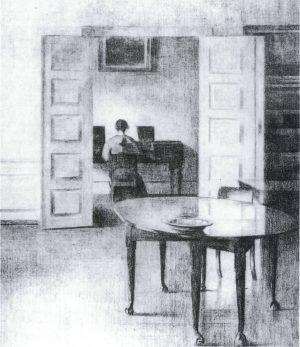

The middle-class novel develops during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in an intensive interplay with the reading woman. She is the new society’s new reader, and to a great extent the new literary genre of the time is addressed to and is about her.

For the middle-class woman who was confined in so many ways, reading was to become both a diversion and an education in the woman’s new role. It also became a much discussed and criticised occupation. It may be that this literature, with its intense discussion of the woman’s new role and the problems concerning it, also became a way of communicating and debating, carrying on a dialogue, among the hemmed-in women.

Femininity, the woman’s existential problems, but above all the woman’s sensitivity, are the central topics in the middle-class novel of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Ian Watt, who has described this development in his classic study The Rise of the Novel (1960), writes that in this period there was “a tendency for literature to become a primarily feminine pursuit” (p. 43).

Or as the German professor Wilhelm Heinrich Riehl put it, in a more indignant way, in 1856:

“In particular, almost all of our belles-lettres is positively henpecked”

(“Namentlich ist schier unsere ganze Belletristik geradezu unter den Pantoffel gekommen”; Riehl, Die Familie, p. 47).

Ever since the development of the book market, women had been its principal consumers; ever since the eighteenth century, they had been the best costumers in the bookshop, the keenest borrowers at the libraries, and the most reliable members of the reading clubs, but their reading had constantly been the object of criticism. And in the later part of the eighteenth and in the beginning of the nineteenth century, when novels are gaining ground in Sweden, this is accompanied by heated discussions about the harmful effect of the genre on its female readers. To the young Louise Munthe in Umeå the conflict is between the useful and the pleasant. The reading of novels is harmful if it distracts the reader from the duties she has to perform, she thinks. However, in the general discussion about the value of novel reading, it is most of all the mental health of the female reader that people worry about: “The only reason for me to hate novel reading, Edvard continued, would be that it swallows up everything else. Just read a page, and you won’t find rest until you have read through all the volumes, until you have read through all that are to be found in the house, in the neighbourhood. […] In any event, I cannot but regard such studies as the least salutary to young women. The tender feelings, the still unnamed desire that is budding in their breast, should not be prematurely ripened or allowed to grow bored, so that they seek an object outside of themselves. Their imagination is still too chaste, too pure, to dwell among ideas that belong to a more advanced age.”

The quotation is from V. F. Palmblad’s dialogue essay “Öfver romanen” (On the Novel). It was published in 1812 in the Romantic writers’ journal Phosphorus, of which Palmblad was also the editor, and is written in the form of a rescue action. The young Mathilda has gone missing for a couple of days. She has hidden herself in her landlady’s library and has with great delight lost herself in the vast collection of novels she has discovered there. Eventually, the rest of the party enters all together to resolutely pull the young woman out from what they almost describe as a state of illness. It is first and foremost the men who feel called upon to do this. The protagonist of the essay, Edvard, who is also the antagonist of the novel, hardly has words sufficient to describe the injurious effect of the reading of novels upon young women. As a monitory example, he describes one of the many disastrous cases:

“I once lived in a small town in Scania in the house of a newly-wed woman, and every morning I saw her lady’s-maid drag home from the lending library packs of damaged and dirty books. With these the otherwise sensible lady would shut herself up, not allowing herself time to eat dinner or sleep at night until she had learned how this or that noble youth in the end got this or that young lady […]. Her household fell into insolvency, her husband became discontented (fortunately, she did not have any children), and she herself was transformed into a shadowy weeping thing, who at the end only felt compassion for fictive misery.”

Palmblad’s portrait of the female reader of novels contains all the ingredients that were typical of the period and that little by little became classic as well. He depicts a female reader who allows herself, without resisting, to be swallowed up by the literature that she herself swallows up – a woman who in her reading cultivates an intense sensitivity while at the same time losing interest in her surroundings and becoming incapable of entertaining true feelings – and he describes how she is broken down and goes to ruin owing to her all too extensive and erroneous reading.

In the beginning of the nineteenth century, simultaneously with the novel becoming a natural part of the young woman’s education and the adult women’s life, the condemnation of it takes root. Novel reading was thought to be unwholesome and to render the reader passive. It made women unrealistic, dreamy, and incapable of living.

In an insoluble paradox, authors like Palmblad pronounce their condemnation of readers of a genre, the development of which they are themselves involved in. It seems as if the century’s male and not least female Swedish novelists constantly have to take into account the low status of their own genre and its alleged negative effects upon the reader.

“Gracious Heaven!”, writes Fredrika Bremer in an essay about “Romanen och Romanerne” (Eng. tr. “The Novel and the Novels”); “had I not then suffered enough from the poisonous stuff? And was I now going to poison others with it?” She recalls the reading of her youth when she had been accompanied by all these “Sophias, Julias, Rosas, Amandas, Alices, Elizas, until I was on the point of losing myself”. The reading of novels had made Fredrika and her sister listen for steps in the night and dream completely unrealistically about being abducted on their way home from church with the family. However, reading had also, and this is worth noting, kept Fredrika Bremer and her hemmed-in sisters emotionally alive in a cold and oppressive patriarchal environment. And in her breakthrough novel, Famillen H*** (1830-31; Eng. tr. The Colonel’s Family), the author steps forward in defence of the novel: “Fluxed with vexation, she said ‘I should rather go without food and drink than be deprived of reading. Is there anything more improving for the soul than reading good books? Anything which better raises the spir… I mean to say raises our thoughts and feelings to … about … to …’”, the young Julia exclaims in Famillen H***. She is an inveterate consumer of novels but cannot help stumbling over the words and blushing when she defends her reading. And she immediately encounters opposition from just about everybody in the party sitting and conversing in the family’s cabinet: “‘If I ever marry’, said a man of about sixty, ‘it will be on condition that my wife never reads any books, with the possible exception of the psalter and her cookery book.’” And Julia’s newly fledged brother-in-law declares with authority: “Novel reading is to the soul as opium is to the body: continuous use of it weakens and harms us.” Unfortunately, even Julia’s fiancé, Arvid, agrees both vociferously and whole-heartedly with this criticism of the novel: “‘Yes by Jove, I cannot understand why womenfolk these days spend so much time reading, by Jove I cannot!’ said Lieutenant Arvid, reaching out to take a handful of sweets from a plate.”

In the course of the novel, Arvid in fact loses his fiancée’s devotion, and on the last pages of the novel she turns out to be very happily married to the somewhat – as it appears at this early stage of the novel – bleary-eyed and cheerless pastor, Professor L. It is also he who stands up for the novel. He surprises Julia and the whole party with a very eloquent exposition on novel reading’s morally and spiritually educating effects, and he finishes his long monologue by stating:

“It is also natural that high-minded young people should love novels as their best friends, when they find in them the great, noble, passionate feelings which they nourish in their own hearts and which have there awakened the first heavenly intimations of happiness and immortality.”

Fredrika Bremer feels called upon to take a stand in the ongoing discussion of the reprehensible effects of novel reading upon the female readers, and in her novel of 1830 she steps forward to defend it. However, if one looks at the other important Swedish female writers of the century, Sophie von Knorring, Emilie Flygare-Carlén, Victoria Benedictsson, and Selma Lagerlöf, one can see how it becomes more and more difficult to handle the condemnation of the novel as the century advances. It eats its way into the female author’s consciousness. She constantly has to take a position on it, and it also seems as if it becomes more and more difficult for her to defend herself against it. In the 1880s, Victoria Benedictsson whole-heartedly endorses the condemnation of the novel, and at the end of the century Selma Lagerlöf has the protagonist of Gösta Berlings saga (1891; Eng. tr. The Story of Gösta Berling) throw the love novel of the century to the wolves, both metaphorically and literally, in a splendid gesture that is, however, hard to interpret.

Yet, in Sophie von Knorring’s novels from the early decades of the nineteenth century, the reading of novels still plays an important and oftentimes positive part. Every now and then her heroines are found with a book in their lap, and they are to an almost comical extent familiar with the novels of the time. In her first novel, Cousinerna (1834; The Cousins), which also became her breakthrough work, no fewer than sixty authors are mentioned, and in Förhoppningar (1843; Expectations) the crucial events take place while the woman and the man are reading in the library. For when Otilia, who has recently become a thirty-year-old widow, discovers the imperfections in her young ward Hugo’s pronunciation of French, she decides that every day he is to read a French text aloud to her. She finds a couple of novels by “someone called Balzac” on the library shelves, but these are promptly rejected, and instead Otilia chooses Lamartine’s Romantic love novel Jocelyn, from 1836. During the reading of Lamartine’s story about a man who sacrifices everything to make his sister happy, the shy Hugo’s emotional life is awakened. For her part, while listening to the young man and conversing with him about what he has read, Otilia is seized with increasing admiration for his beautiful and pure thoughts. In the shelter of their reading they discover an ardent and intense friendship, which is instantly transformed into passion – and which drives both of them towards catastrophe.

The emotions that literature has elicited in the man and the woman bring them together for a short while, but later on they develop in separate directions. At first, it looks as if the novel reading has not brought about anything good, apart from a brief intoxication. But when Hugo loses Otilia, it turns out that the feelings that the reading has awakened in him have set a deeper mark than could have been suspected at an earlier point, and he comes to maturity as the distinguished man whom Otilia thought that she was seeing in the library.

The novel Förhoppningar (1843; Expectations) is a very self-aware meta-novel about different types of novel reading. Parallel with the plot, Sophie von Knorring also ironically comments on how her novel will be received by the reading public – and by the severe critics – by way of a fictive framework. The book is read aloud by Mrs D. to Mrs C. (thus, in this three-volume novel the chapters are called “readings”). These hardened female readers are accustomed to literature along the lines of Sue’s Paris novels and are suspicious of “yet another of these true pictures out of this everyday life that we are so very tired of”. With a fine sense of humour Knorring describes their reluctant but growing fascination. Little by little their objections fall silent, and the novel occupies, without comments, their – and our – full attention. It is an ingenious and clever literary device.

The same double narration of the blessing and curse of literature is found in Emilie Flygare-Carlén, who, incidentally, according to her autobiography was named after the heroine in one of Lamartine’s novels, since he was her mother’s favourite author. In Romanhjeltinnan (1849; The Heroine of the Novel), Emilie Flygare-Carlén explicitly condemns the reading of novels. The protagonist, who has grown up on a diet of chivalric romances and family novels (since her mother considered these to be the very best), entertains a devastatingly romantic view of reality. Her name is Blenda, and she is, as it were, blinded by literature. “Not once did it occur to the good-natured lady to consider that all this poetic and soft nourishment, enjoyed to such excess, could be harmful to her beloved Blenda”, writes Emilie Flygare-Carlén, and time and again she returns to the danger of devouring novels. Reading has wrapped Blenda up in dangerous illusions, and her mother’s sister, who is also a sworn opponent of novel reading, fears that she will be easy prey for the first fortune-hunter who comes along.

Nonetheless, the desire to read novels becomes Blenda’s road to happiness. On her journey from Vänersborg to Stockholm, where she is going to stay with her aunt, she meets a man, and during their conversation about novels he expresses his surprise at her taste. Before he takes his leave, he presents her with a parcel of books. It does not contain any works by her favourite authors, but more realistic novels. However, this library of novels becomes her most treasured possession.

Emilie Flygare-Carlén contrasts two types of novels, the romantic and the realistic, and even if she herself in many ways writes in the spirit of the former, in her explicit appraisals we find a plea for the latter. However, in both of Victoria Benedictsson’s novels, Pengar (1885; Eng. tr. Money) and Fru Marianne (1887; Mrs Marianne), the author is, if anything, altogether dismissive of novel reading. In Pengar, the enervated, ignorant, and immature aspects of Richard’s wife find their clearest expression in the fact that she prefers to lie on the couch reading novels, whereas the grandeur of the protagonist, Selma, is indicated by her intensive reading of non-fiction books. Likewise, it is when Richard sees the impressive private collection of scientific books that Selma has built, that he realises her true qualities.

Mrs Marianne in the eponymous novel has, however, like Flaubert’s Emma Bovary in Madame Bovary (1857), been completely ruined by literature.

When, in 1857, in his classic novel Madame Bovary, Gustave Flaubert has that reader of novels, Emma Bovary, die from reading, he is building on an established tradition. “Even at table she had her book by her, and turned over the pages while Charles ate and talked to her”, Flaubert writes disapprovingly. Emma stops eating. She stops speaking with her husband; she does not even listen to him. She just reads. And Flaubert has her heading towards a horrible end. When she tosses about, sweating, ugly, and full of anxiety, in one of the most repugnant death scenes in the history of literature, there is absolutely no doubt that she is just as much a victim of her own desire to read as of the arsenic she has swallowed. And just as she is unable, despite terrible vomiting and convulsion, to free herself of the medicinal poison, so her psyche is unable to free itself of the mental poison she has partaken so greedily of through her reading. Just like the reader whom Palmblad, the standard-bearer of Swedish Romanticism, described towards the beginning of the century, so Flaubert’s female reader of novels is heading for her ruin.

She cannot discern between life and literature, they constantly slide into each other, and her intensive novel reading prevents her from seeing and accepting life as it is. “She had put down the book to read the letter”, it says when she has received her future husband’s letter of proposal, “and after having finished reading it she lay still, dreamily gazing out into the room. The anticipation of a realistic novel spread into her imagination like a mist”. To Marianne, as to Emma Bovary, marriage indeed turns out to be a disappointment, and she loses herself in the novels: “To fill the emptiness and assuage her anguish, Marianne had only one way out: the novels. In her imagination she lived the life that reality had begrudged her.” She “sucked the eroticism of the novels as a child sucks its thumb”, writes Victoria Benedictsson. When Pål, the depraved childhood friend of her husband, turns up in the middle of her novel reading, Marianne’s fate seems to be sealed. But unlike Emma, Marianne does not founder. When she realises that her romantic ideal has nearly driven her into a situation in which it might as well be Pål as her husband who is the father of the child that is growing inside her, she turns away in disgust from the novels and throws herself into the housework that she has until now neglected. Eventually, she also lays out a big and beautiful garden around the house, where industry now prevails; and the time of novel reading is over, once and for all.

At the end of the century, Victoria Benedictsson endorses the established verdict on the female reader of novels, although she recognises the possibilities for her development. In Gösta Berlings saga, Selma Lagerlöf makes a move that is harder to interpret. She has her protagonist, Gösta Berling, “the poet”, throw the Romantic love novel to the wolves in a grandiose gesture, but at the same time she clearly writes in that very tradition, and her condemnation of the novel can just as well be seen as its definitive rehabilitation.

When Gösta, after having hitched his horse Don Juan to the sledge in order to set off for the Christmas ball at Borg, stops to eat dinner at the Berga farm, he certainly comes upon the traditional female reader of novels. The captain’s wife at Berga, the matron of the farm, has not as yet gotten out of bed. “She lay abed and read novels, just as she had always done”, writes Selma Lagerlöf. And at first Selma Lagerlöf appears to wholeheartedly join the tradition of condemnation. According to Edvard, the Romantic writer Palmblad’s novel hater from the beginning of the century, it is exactly the disarray and decay reigning at Berga that is the natural consequence when ladies read novels. There is hardly anything to eat; the housekeeper has gone to the village to find some horseradish for the tough meat being served for dinner; and furthermore, everybody is in despair because the lovely and rich Anna Stjärnhök, who had promised to marry the son of the house, now intends to get engaged to someone else. However, Gösta Berling is seized with compassion, promises to bring back the unfaithful, and before the night is over the novel will have proven its power.

Just as Gösta Berling is about to leave, the captain’s wife comes out onto the stairs. In her hand she holds her dearest belongings, three little books, bound in red, and she presents them to Gösta as a parting gift and a blessing: “‘Take them’, she said to Gösta, who already sat in the sledge; ‘take them, if you fail! It is ‘Corinne’, Madame de Staël’s ‘Corinne’.’”

Germaine de Staël’s Corinne from 1807 was the success novel of the century, read and discussed as no other novel. It is the prototype of women’s favourite reading, and it was to save not only Gösta Berling and Anna Stjärnhök but also the Berga farm.

“That was a wild drive through the night. Absorbed in their love, they let Don Juan take his own pace”, writes Selma Lagerlöf. Just as in a traditional love novel, Gösta Berling and Anna Stjärnhök fall in love. Their feelings defy all calculations, and the young couple streak forward through the snow. But soon wolves appear out of the darkness of the night. Gösta whips his Don Juan, but the beasts come closer and closer. For a brief moment they are distracted by the green travel sash that Gösta has been given by the evil Sintram himself, but it is not until Gösta Berling casts Germaine de Staël’s Corinne into their jaws that the wolves give up and Gösta turns the sledge around towards Berga.

The novel reader gets her farm back, but at the cost of her reading, one might say, if it were not for the fact that Selma Lagerlöf, in Gösta Berlings saga, resurrects the love novel again and again. Just as the boar Särimner in Nordic mythology, the novel is torn to pieces and consumed time after time, only to be regenerated and to demonstrate anew its power and charm, as it did on the book market as well.

Translated by Pernille Harsting