A man shall trust not

the oath of a maid,

Nor the word a woman speaks

(“The Sayings of the High One”)

Meyjar orðum

skyli manngi trúa

né því er kveður kona

(“Hávamál”)

Nordic women’s literature builds on an age-old tradition with roots back to Norse culture and pre-literate times. There are many indications that women were largely responsible for the oral tradition in Norse literature, not least the eddic narrative poems which by and large thematise women’s experience and have a female perspective. The poetry was linked to the art of divination known as seid and to the healing arts, both of which were predominantly female spheres; that is to say, poetry, seid and healing arts were components of one and the same system, forming a ritual unit.

In range, Norse literature spans the transition from paganism to Christianity and from an oral to a written culture. There is a concurrent movement from a strongly women-centric to a virtually one-sided male-dominated culture.

With monotheism, and later Christianity, monasteries, writing, and schools – and not least the introduction and growth of literary institutions in thirteenth-century Iceland with the enormous scope and influence of the written enterprise undertaken by Snorri Sturlason (1179-1241) – this women-centric culture was repressed and/or usurped by the male culture. The introduction of Christianity deprived women of many important roles in the execution of pagan rituals, and they did not learn to write, either. This meant that the women’s oral tradition was, in a very literal sense, silenced by the pens of the male culture.

This apocalypse of the female culture can be observed at many junctures in Norse literature, expressed in myths, structures and metaphors.

The authorship of the greater part of Norse literature is unknown. The known names considered to be historical literary figures are nearly all male. Not one single work of prose is ascribed to a woman, and only a tiny fraction of the approximately 250 extant poems by known writers is attributed to women. In addition, more female than male writing has been lost. In the old skaldic catalogues, female names are for the most part written in the margin, and in one instance the writer makes his apologies for having considered women to be skalds. Much of the writing took place in the monasteries. In the Middle Ages there were two convents in Iceland, one founded in 1186 and the other in 1296. In all likelihood, the nuns worked with books and scholarship in exactly the same way as the monks in their monasteries, but of this activity we no longer have any testimony.

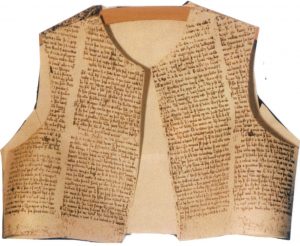

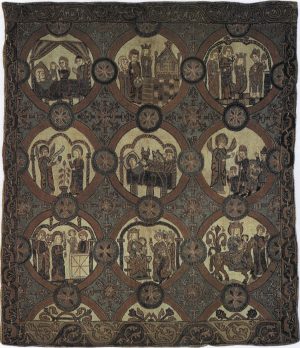

The names of literary or learned women occur are extremely rare in the extant literature of the time. For example, in Íslendingabók (c. 1125; Book of the Icelanders) Ari Þorgilsson “the Wise” refers to Þuríður Snorradóttir as “both very wise and not unreliable”. In one of the Biskupa sögur (Bishops’ Sagas), Þorláks saga helga (c. 1200; The Life of Saint Thorlak), we read that when, in his youth, the bishop had nothing else to do he listened to what Halla “his mother, knew how to teach him about genealogies and knowledge of people”. In another bishop’s saga, Jóns saga helga (also c. 1200; Life of St Jón of Hólar), we learn about school instruction at the episcopal residence of Hólar in the early twelfth century, and special attention is drawn to the fact that one of the students is female. Characteristically, she is nonetheless mentioned as the last in a list of male students and only by her first name. She is an exceptional girl called Ingunn, who is well-versed in literary knowledge, very good at Latin and gladly teaches others who want to learn. She made corrections in the Latin books copied there by having them read aloud to her, while “she sewed, played board games, or did embroidery or weaving, depicting legends of the saints. In this way she made God’s glory known to men not only by the words of oral instruction but also by the work of her hands.”

Elsewhere in Jóns saga helga we see censorship by the Church: “An unseemly pastime was popular in which people recited back and forth, a man to a woman, and a woman to a man, verses which were disgraceful and shameful and disgusting. He abolished it and prohibited it unequivocally. He would not listen to erotic poems or verses, or permit them to be recited, but he was unable to abolish them entirely.” The Bishop is particularly opposed to “mansöngrinn”, woman’s song.

This young woman at the episcopal school learns neither to read nor write, but she is put to work teaching others because she is so knowledgeable in the narrative arts and oral learning. While talking she uses embroidery to depict the men’s heroic deeds, a motif which later appeared in heroic poems and also became common in writing of a later date. The story of this young woman is a good example of censorship by the literary establishment: it only features in the older version of the saga; in the more recent version it was cut.

The word “man” originally means woman and is etymologically linked to “mine” in the German word “minnesang” – a poetic genre originally developed by women. In Jóns saga helga the word “mansongr” also clearly means woman’s song. This is the only evidence we can find in the Norse sources for a “minnesang” of this type, which might have existed as a female genre, but has been lost.

Laxdœla saga (c. 1245; Laxdale Saga) contains a highly symbolic story about the Irish princess and slave Melkorka who rebelled against her oppression simply by keeping silent and pretending to be a mute. Early one morning when her husband and father of their infant son, Olaf, goes out to look around the manor grounds, he hears someone speaking and he “went down to where a little brook ran past the home-field slope, and he saw two people there whom he recognised as his son Olaf and his mother, and he discovered she was not speechless, for she was talking a great deal to the boy.”

This scene, with the silent mother who talks to her son and teaches him his ‘mother tongue’, has been interpreted as a metaphor for women’s hidden but strong influence on male written literature. Because of their strong oral, domestic narrative tradition, which they passed on to their writing sons, this literature was written in Icelandic rather than in Latin – the language of literary establishments elsewhere in Europe.

In his article “Sex and Vernacular in Medieval Iceland” (1971), Robert Kellogg interprets the scene with the silent mother in precisely this way.

In extension of this theory, it can also be said that women’s outlook, voices and experiences are most clearly heard in the unattributed writings and in genres that are largely based on oral tradition.

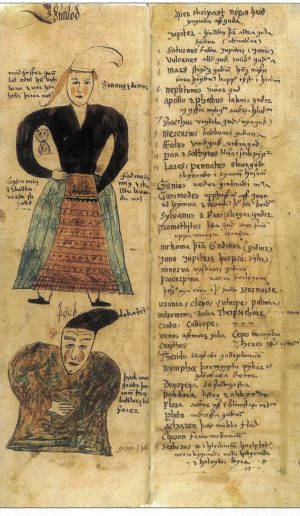

Norse literature covers a period of approximately 500 years (900-1400). Most was written in Icelandic and in Iceland. Eddic poetry and the legendary tales of Icelandic prehistory are divided into mythological poems, dealing with the gods and their stories, and heroic poems, dealing with a long-since vanished Central European heroic world. The somewhat later Sagas of the Icelanders are more realistic in narrative style. The sagas treat of the first generations of Icelanders, and are in part based on historical events. In these three genres the author is always anonymous. This is not the case with skaldic poetry, which is often addressed to foreign kings. These verses were composed and presented by named poets, known as skalds. Furthermore, there were kings’ sagas, written by assigned authors, and bishops’ sagas and sagas of contemporary history (“Sturlunga saga”), of which many have named authors. In addition, there were various didactic works: for example, textbooks of grammar and rhetoric. The translated literature comprised chivalric sagas and legends.

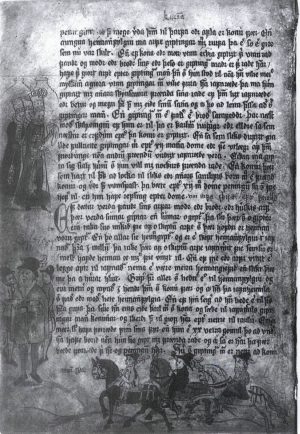

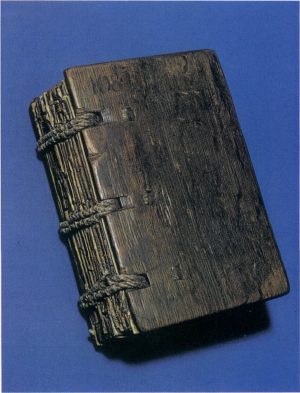

The extant literary tradition is problematic and is the subject of controversy. Norse literature is based, to a greater or lesser extent, on ancient, oral traditions. It was worked up and written down in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries and handed down in even later manuscripts. Thus, the Codex Regius, the manuscript containing the eddic poems, is dated to c. 1270, and the more extensive saga manuscripts Möðruvallabók, Flateyjarbók and Hauksbók to the period between 1300 and 1390.

Great-Grandmother

In this context, the name Edda on Snorri Sturlason’s handbook of poetics is of great interest. “This book is called Edda, and Snorri Sturluson compiled it”, states the oldest manuscript containing the book, whereas later manuscripts do not have titles. The word then appears in the Edda itself, in a list of synonyms for women. Here it has the meaning ‘foremother’ or ‘great-grandmother’, and is followed by synonyms for the next two generations of mothers. This is also how it is used in the poem “Rígsþula” (Song of Ríg, or Lay of Ríg), where a grey-haired Edda has a son with the god Heimdal, and thus becomes the original ‘mother’ of the first human race, that is, the class of thralls.

Most scholars agree that edda means great-grandmother, while many resist linking this to the name of the book. Various etymologies and explanations have been proposed:

1) That the name means great-grandmother and either refers to women as the carriers of tradition or to the old material in the book, coming from great-grandmother’s day.

2) That the name comes from the word æði (ecstasy), (adj. óðr, ‘raging’) and refers both to the poet’s trance-like state and to inspiration.

3) That the name stems from óður (ode) and means poetry or poetics.

4) That it derives from the estate name Oddi, by means of which Snorri wanted to commemorate the place where he grew up.

5) That the name comes from the Latin verb edo, in the derived sense of either ‘edit/compile’ or ‘compose’.

The first three interpretations are proposed from the perspective of the oral tradition, whereas the last two link the name with education and the literary institution (the seat of learning, Latin). Thus, the entire research history displays an aversion to the idea that women had anything to do with eddic poetry and the Prose Edda.

The word edda can also be linked to both æði (ecstasy) and óður (poetry). The noun óður additionally means spirit or inspiration, and it is also by virtue of these interwoven qualities that the god Odin acquired his name. In mythology, poetry and ecstasy/inspiration belong to the same sphere, which is clearly seen in depictions of seid. The word edda thus contains the components ecstasy, inspiration, poetry, woman and old. In addition, it suggests that old women were called eddur precisely because they composed and spoke “odes”. This in turn means that they were not only ‘carriers of tradition’, but poets and active creators of tradition in their own right. It is interesting to note that they are characterised as “old”. This pattern is repeated in the sources as a metaphor for a lost or vanishing female culture that only exists in the memories of old women.

The word edda, in the name of the eddic writings, was first used in the seventeenth century by Bishop Brynjólfur Sveinsson, when the only extant manuscript of the texts came into his possession in 1643. He later presented the manuscript, Codex Regius, as a gift to the king of Denmark. Before Brynjólfur obtained the manuscript he had believed, like everyone else, that these writings had been forever lost, and in a letter to a friend in Denmark he lamented posterity’s lack of understanding for, and destruction of, the intellectual and spiritual inheritance of the ancient past. “Where,” he writes, “is the vast treasure of human wisdom which Sæmundr fróði collected, above all that Edda of which we have barely one thousandth left; it would all have been lost had Snorri Sturlason not made an excerpt, which can but be compared with a shadow.” However, he links the old poems, which he imagines were compiled by the legendary sage Sæmundr fróði (Sæmundr the Learned, 1056-1133), with Snorri’s use of them and with the name of his book. To Brynjólfur’s mind, there is thus a connection between poetry and edda (great-grandmother). Having acquired the manuscript, the Bishop had a transcript made, and on the first page of the copy he put the heading: “Edda Sæmundi multiscii” (Edda of Sæmundr the Learned). The name has since stuck to this collection of mythical and heroic poetry. In literary history, Jón Helgason has explained this as being a result of the Bishop’s misconstruction and his lively imagination.

The Prose Edda is an instruction manual in poetics, in which Snorri explicitly teaches young poets how to make use of old traditions, that is, the eddic narratives in their skaldic poetry: “But now one thing must be said to young skalds, to such as yearn to attain to the craft of poesy and to increase their store of figures with traditional metaphors; or to those who crave to acquire the faculty of discerning what is said in hidden phrase: let such an one, then, interpret this book to his instruction and pleasure. Yet one is not so to forget or discredit these traditions as to remove from poesy those ancient metaphors with which it has pleased Chief Skalds to be content.”

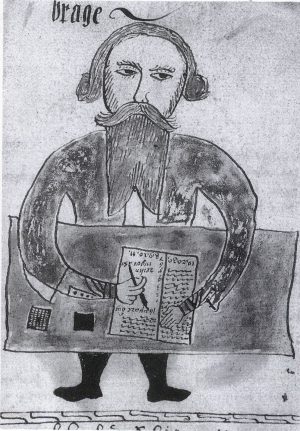

“Most skalds,” he says, “have made verses and divers short tales from these sagas.” He later cites a verse from “Ragnarsdrápa” (a skaldic shield drápa composed in honour of Ragnar Lodbrok), attributed to Bragi Boddason the Old who, besides being the first named poet in the annals of Nordic literature, is tellingly synonymous with the mythological Norse god of poetry. Of him it is said elsewhere in the Prose Edda: “One is called Bragi: he is renowned for wisdom, and most of all for fluency of speech and skill with words. He knows most of skaldship, and after him skaldship is called bragr, and from his name that one is called bragr-man or -woman, who possesses eloquence surpassing others, of women or of men.”

Bragi was not only the first skaldic poet, he was also the first to make use of material from the eddic poetry in his verse. The poem cited a number of times by Snorri was written in honour of King Ragnar Lodbrog, and in gratitude for the shield he had given the poet. Bragi takes the poem’s metaphors from eddic poetry – not directly, however, because they had been painted on the shield, which he then describes, that is, they had been fixed in a form of writing.

The shield metaphor links skaldic poetry to weapons and warfare, a typically male culture. It also demonstrates that writing had become a trade – the poet supplied a tribute verse and received a gift in return. Skalds were most often rewarded for their poems with weapons or other battle equipment such as armour or vessels. They were also awarded long residencies at the royal court, often as the king’s chronicler.

Snorri cites various eddic poems in Edda, but he reformulates most of them in prose with his own epic wording. Some of the legends are only found in his version, possibly based on eddic poems that have now vanished completely. Elsewhere, when writing became institutionalised, we see a similar transformation of oral and anonymous poetry into prose. Thus, the eddic poetry forms the basis not only for skaldic poetry but also for some of the legendary tales, and this could well explain why most of the eddic poetry has only survived in a single and, moreover, damaged manuscript.

Myth of the Skaldic Mead

The god Odin of Norse mythology can be perceived as a metaphor for the transition from an oral women’s culture to a male-dominated written culture. Various domains in women’s culture are gradually appropriated – as are various women. He conquers, for example, the world itself, personified in female form, and sires a son and ally, Thor, the strongest of all. Basically, the aim of the entire canon of Norse mythology is to show how the gods conquered nature, the untamed and the wild, and established a society. Firstly, they built a fortress around the earth to divide it off from the ocean; later they built the fortress Midgard, and within that Asgard. These entrenchments protected them from giants and other monsters. However, they still had to leave their dwelling place to seek the wisdom that lay hidden on the outside; led by Odin, they conquered it with force and guile. This appropriation of nature and wisdom is also a theme in many of the eddic poems, where it is often connected to mastery of language and the power of language.

In the myth of the skaldic mead, as told in the Prose Edda, Odin attains the gift of poetry through a woman. The mead was originally brewed in the wilderness by two dwarves. They killed the wisest giant and let his blood run into two vessels, Son and Bodn, and into the kettle Odrarer. They then mixed honey with the blood, “and thus was produced such mead that whoever drinks from it becomes a skald and sage”. The giant Suttung is given the mead, takes it to Hnitbjorg and puts it in the safekeeping of his daughter Gunlad. Odin hears about this, assumes the name Bolverk (i.e. evildoer), and strikes a bargain with the giant Bauge, Suttung’s brother and Gunlad’s uncle, to try to get the mead. The giant Suttung refuses to cooperate, and will not give away so much as a drop of the mead.

“Bolverk then proposed to Bauge that they should try whether they could not get at the mead by the aid of some trick, and Bauge agreed to this. Then Bolverk drew forth the auger which is called Rate, and requested Bauge to bore a hole through the rock, if the auger was sharp enough. He did so. Then said Bauge that there was a hole through the rock; but Bolverk blowed into the hole that the auger had made, and the chips flew back into his face. Thus he saw that Bauge intended to deceive him, and commanded him to bore through. Bauge bored again, and when Bolverk blew a second time the chips flew inward. Now Bolverk changed himself into the likeness of a serpent and crept into the auger-hole. Bauge thrust after him with the auger, but missed him. Bolverk went to where Gunlad was, and shared her couch for three nights. She then promised to give him three draughts from the mead. With the first draught he emptied Odrarer, in the second Bodn, and in the third Son, and thus he had all the mead. Then he took on the guise of an eagle, and flew off as fast as he could. When Suttung saw the flight of the eagle, he also took on the shape of an eagle and flew after him. When the asas saw Odin coming, they set their jars out in the yard. When Odin reached Asgard, he spewed the mead up into the jars. He was, however, so near being caught by Suttung, that he sent some of the mead after him backward, and as no care was taken of this, anybody that wished might have it. This we call the share of poetasters. But Suttung’s mead Odin gave to the asas and to those men who are able to make verses. Hence we call songship Odin’s prey, Odin’s find, Odin’s drink, Odin’s gift, and the drink of the asas.”

In the myth of the skaldic mead, the giantess Gunlad, confined in a mountain in the wilderness, guards the mead of poetry. Symbolically, she is on the boundary line of culture, and she transmits the mead from the wild chaos to the literary, male institution. The auger, Rate, used by Bolverk and his helper to bore a hole through the mountain rock, is patently a phallic symbol. In accordance with this metaphor, Odin turns himself into a serpent and creeps through the hole. Once he has conquered Gunlad with his phallus, he deceives her and drinks all the mead. She is left behind, while he flies away in the guise of an eagle, back to Asgard and the established order.

The drink in this story, as is generally the case in Old Norse literature, is an interesting motif. Women prepare the drink and give it to the men, who do the drinking. The drink is the source of life and creativity, but also of intoxication, and as such it can be dangerous because it obliterates the boundaries between the established and the wild.

The legend on which Snorri bases his story also occurs in the mythological poem “Hávamál” (Sayings of the High One), which is narrated by Odin as he gives an account of his conquests – often with a remarkable double voice. In the verses on Gunlad and the mead, the subject alternates between a triumphant Odin – who boasts: “What I won from her/ I have well used/ little is lacking to the wise” – and an unidentified counter-voice that speaks with most authority in the concluding verse of the story:

Odin swore,

I think, an oath on the ring

though who shall trust in his word?

By fraud he has

robbed Suttung’s mead

and caused Gunlad to grieve.

This is a somewhat different perspective to that taken by Snorri, who follows Odin on his flight while the mountain closes around Gunlad. The poem problematises the words themselves, the language of the dominant culture. Once Gunlad has been abandoned, deceived and robbed, there is nothing left for her to do but weep. She uses body language against the man’s deceitful words. Weeping is the woman’s form of expression, and in heroic poetry weeping became a poetic genre, grátur.

Poetry and Seid

Ynglinga saga, the first part of Snorri’s chronicles of the ancient Norse kings in Heimskringla, contains a story about the origins of seid, in which Snorri traces it back to the goddess Freya, who “first taught the Asaland people the magic art”. Not long afterwards, however, he would seem to have forgotten this point, because now Odin is the grand master and creator of seid:

“Odin understood also the art in which the greatest power is lodged, and which he himself practised; namely, what is called magic. By means of this he could know beforehand the predestined fate of men, or their not yet completed lot; and also bring on the death, ill-luck, or bad health of people, and take the strength or wit from one person and give it to another. But after such witchcraft followed such weakness and anxiety, that it was not thought respectable for men to practise it; and therefore the priestesses were brought up in this art. Odin knew finely where all missing cattle were concealed under the earth, and understood the songs by which the earth, the hills, the stones, and mounds were opened to him; and he bound those who dwell in them by the power of his word, and went in and took what he pleased.”

Odin has mastered the magic power of seid and, according to Snorri, he is the one who spreads it to others. The meaning of the word seid (seiður) is unclear and – like the manner in which seid is presented – a much discussed issue. As seen in this passage, song is an important component of seid: Odin “understood the songs by which the earth, the hills, the stones, and mounds were opened to him”. In terms of etymology, too, the word seid can be connected to the word song; and seid is often linked thematically with writing and the power of language. It is therefore most likely that seid means a type of song. Of Odin, Snorri goes on to say:

“Another cause was, that he conversed so cleverly and smoothly, that all who heard believed him. He spoke everything in rhyme, such as now composed, which we call scald-craft.”

In the current context, the most important aspect of seid is its association with homosexuality. If a man engages in the practice of seid – of which there are many examples in both the saga literature and the eddic poetry – he is usually considered to be argr, meaning unmanly, that is, homosexual or closely related to the seid woman.

The sources refer to women who practise seid as “völva”, “seid women”, “female seers” or “wise women”. The many and often imprecise terms could seem to suggest that the difference between them, if there was any, was no longer recognised. Philology has taken it as fact that the word völva comes from völur (wand, staff) and means ‘wand carrier’. The völva would thus have taken her name from the seid staff she carries in some of the tales. However, it is more likely that the word has the same stem as the Latin verb volvere (tumble, turn) and refers to the trance into which the völva falls – her ability to see into another world.

The stories about these women reveal a distinct narrative pattern:

The völva is summoned to an estate. Metaphorically, and from an Icelandic viewpoint, she comes from the wilderness, most often Greenland, Lapland or the Hebrides. The völva is an old woman; the men lay claim to her knowledge. She is paid for her prophecy (in the form of gifts); being a völva was thus a job. The völva sits on a raised seat, and her sight or vision is much revered. She sings or speaks her prophecy; some believe it while others, always young men and usually a couple of “sworn brothers”, doubt the prophecy and attempt to silence her. Christianity is often portrayed as the völva’s adversary. She places great weight on her words, which turn out to come true.

This myth occurs in a number of variations that trace a specific process: first the völva is revered, thereafter derided and threatened, and finally abused, wounded and killed.

The most detailed depiction of seid is found in Eiríks saga rauða (Saga of Erik the Red). The story is set in Greenland. There is a shortage of food in the country, and Thorkell, the chief franklin of the settlement, summons the woman Thorbjorg to his home to find out when the hardship will cease. The young woman Gudrid and her father Thorbjorn, both recently arrived from Iceland, are also staying at the homestead. Thorbjorg is termed a “prophetess, and was called Litilvolva”. She is said to have once had nine sisters, all of whom had been prophetesses, but she was the only one still alive. Throughout the winter this woman travels around visiting people in their homes, “especially those who had any curiosity about the season, or desired to know their fate”. Thorbjorg is given a hearty welcome, “as was the custom wherever a reception was accorded a woman of this kind”, and a high seat is prepared for her.

On the first day the völva “remained silent altogether” and would give no answers until she had slept there for the night and had become familiar with the house: “And when the (next) day was far spent, the preparations were made for her which she required for the exercise of her enchantments. She begged them to bring to her those women who were acquainted with the lore needed for the exercise of the enchantments, and which is known by the name of Weird-songs [Varðlokur], but no such women came forward. Then was search made throughout the homestead if any woman were so learned. Then answered Gudrid, ‘I am not skilled in deep learning, nor am I a wise-woman, although Halldis, my foster-mother, taught me, in Iceland, the lore which she called Weird-songs.’ ‘Then art thou wise in good season,’ answered Thorbjorg; but Gudrid replied, ‘That lore and the ceremony are of such a kind, that I purpose to be of no assistance therein, because I am a Christian woman.’” Thorkell “thereupon urged Gudrid to consent”, we are told, and she yields and does as he wishes:

“The women formed a ring round about, and Thorbjorg ascended the scaffold and the seat prepared for her enchantments. Then sang Gudrid the weird-song in so beautiful and excellent a manner, that to no one there did it seem that he had ever before heard the song in voice so beautiful as now. The spae-queen [prophetess] thanked her for the song. ‘Many spirits,’ said she, ‘have been present under its charm, and were pleased to listen to the song, who before would turn away from us, and grant us no such homage. And now are many things clear to me which before were hidden both from me and others.’”

The völva has good news for Thorkell and the settlement. The scarcity of food will come to an end, as will the epidemic of illness. “And thee, Gudrid, will I recompense straightway, for that aid of thine which has stood us in good stead; because thy destiny is now clear to me, and foreseen.” Gudrid’s reward is an excellent match in Greenland, but the marriage will not be long-lived because she will return to Iceland where she will become the foremother of a long and goodly family line. One after the other then approach “the wise-woman” and ask her about what they are most curious to know. She is liberal with her replies, “and what she said proved true”. Thorbjorg is immediately summoned to another homestead, and once she has left Thorbjorn, Gudrid’s father, is sent for “because he did not wish to remain at home while such heathen worship was performing”.

The myth of the wise woman who imparts her knowledge before disappearing occurs in a number of the eddic poems. “Baldurs draumar” (Baldr’s dreams, also called Vegtamskviða) is a dialogue between Odin and a völva he has resurrected from the realm of the dead. It begins with Odin, who wants to know why his son Baldr has been having such bad dreams, riding to a place “he knew well, / was the wise-woman’s grave”. The völva does not like being disturbed: “I was snowed on with snow, / and smitten with rain, / And drenched with dew; / long was I dead.” The subsequent stanzas consist of questions and answers, confrontations in words. The völva ends all her responses with: “Unwilling I spake, / and now would be still.” Parallel to this, Odin opens his questions with: “Wise-woman, cease not! / I seek from thee / All to know / that I fain would ask.” Once she has told him everything he wants to know, he plays his card: “No wise-woman art thou,/ nor wisdom hast; / Of giants three / the mother art thou.” She in turn threatens him with the apocalypse, Ragnarök, and has the last word. In “Grógaldur” (Gróa’s Chant), interestingly, the völva has become a mother who counsels her son. Long since dead and buried, she still talks to him, and her chant is defined as his “mother’s words”.

In this account the völva is treated respectfully, but she is the only one left of ten sisters, all prophetesses. The women’s culture is vanishing. In the practice of seid she needs women who can sing or speak a particular poem, but these women are not to be found. Christianity is set up as a conflicting alternative. Gudrid refuses to sing because she is a Christian and, as she says herself, she is neither possessed of the required knowledge nor is she a wise woman. The woman who taught her the lore and the song is her old foster-mother in Iceland, which would suggest that, seen from an Icelandic viewpoint, in Gudrid seid had already moved from the established culture out into the borderlands. It is impossible to find an explanation for the name of the poem, and the content itself has been lost. The sagas have several accounts of how the women’s words cannot be understood; their incantations, seid and verses are something old and incomprehensible.

The Prose Edda has an entertaining story that perfectly illustrates the perception of völvas and their connection with the healing arts. The god Thor has been hit by a hone (or whetstone) which is now stuck in his head. He seeks help from the völva Gróa and, it is said, even though she was most concerned about the disappearance of her husband, Aurvandill, she sang her spells over Thor until the hone was loosened, “But when Thor knew that, and thought that there was hope that the hone might be removed, he desired to reward Gróa for her leech-craft and make her glad, and told her these things: that he had waded from the north over Icy Stream and had borne Aurvandill in a basket on his back from the north out of Jötunheim. And he added for a token, that one of Aurvandill’s toes had stuck out of the basket, and became frozen; wherefore Thor broke it off and cast it up into the heavens, and made thereof the star called Aurvandill’s Toe. Thor said that it would not be long ere Aurvandill came home: but Gróa was so rejoiced that she forgot her incantations, and the hone was not loosened, and stands yet in Thor’s head.”

Manly Thor has to bow to the skill of the völva! Incantations have replaced seid; but incantations are also sung, presented within a formula of some sort, like a poem. This story also exemplifies the grotesque humour characteristic of the Prose Edda and writing about the gods in general – a humour which often sows doubt about the virility and brave deeds of the heroes.

Völva Persecutions

Things gradually go from bad to worse for the völvas. Vatnsdœla saga (Saga of the People of Vatnsdal) and Örvar-Odds saga (Saga of Arrow-Odd) present a pattern of events that adds up to what could be called the onset of the ‘völva persecutions’.

One of the first chapters of Vatnsdœla saga – one set in Norway – tells the story of a feast on an estate at which the host arranges for seid so that people can find out what their future holds in store. The völva is from Finnmark, she is versed in magic rites, and it is said that the seid was prepared “in the old heathen fashion”:

“The Lapp woman, splendidly attired, sat on a high seat. Men left their benches and went forward to ask about their destinies. For each of them she predicted that which eventually came to pass, but each took the news in a different way. The foster-brothers sat in their places and did not go up to enquire about the future; they placed no trust in her predictions. The seeress said, ‘Why do those young men not ask about their futures, because they seem to me to be the most outstanding of the men assembled here?’ Ingimund answered, ‘It is not important for me to know my future before it happens, and I do not think that my future lies at the roots of your tongue.’”

The foster-brothers here function as a pair, and the emphasis is on their youth and virility, whereas the völva represents the old. Ambivalence to the völva emerges when the one foster-brother, the son of the farmer on the estate, doubts her abilities, while the other, who has come from outside the estate, protests loudly. He gibes at the völva, does not believe what she says and tries to have her silenced – she is not going to utter a word about him. The confrontation is described in highly metaphorical terms, given that he refuses to see his fate “at the roots of your tongue”. The pattern dictates that the völva will speak anyway, after which she and the young man will quarrel. She then makes a positive prophecy for his future, as völvas generally do: he will settle in Iceland, becoming a respected man and living to a great age. He replies that he will never go to those settlements in the wilderness. The völva insists that what she says is true, and the episode ends with Ingimund threatening her: “If it were not for offending my foster-father, you would receive your reward on your skull”, and he adds that ill-fortune had brought her there. The völva repeats that things will undoubtedly turn out as she said, “whether he liked it or not”.

The story told in the legendary tale Örvar-Odds saga is more detailed and more directly linked to poetry and the power of language. The völva is the main character in the episode, which both begins and ends with her: “There was a witch woman called Heid who had second sight, so with her uncanny knowledge she knew all about things before they happened.” This woman travels around to the farms accompanied by a choir of fifteen boys and fifteen girls, recalling the singing episode in the saga of Erik the Red. A well-to-do farmer wants to invite her to his farm and he asks his foster-son Odd to go and fetch her. Odd refuses. He fiercely opposes the invitation and threatens to do something bad if the völva comes. So the farmer sends his own son to get her, but he and Odd have become “sworn brothers”. The völva and all her entourage arrive, and they are initially made welcome. She performs seid during the night, and the following day the people on the farm come to her and she has pleasing predictions for all of them. She also predicts the weather for the coming winter and “a lot more that was not previously known”. The farmer thanks her for “her prophecies”. She asks if she has seen everyone in the household and he replies that she has – almost. As they talk she notices something moving under a cloak on a bench, and she wants to know what it is: “At that moment the one lying under the cloak sat up and said, ‘It’s just as you think, there is someone here, and what that someone would like would be for you to shut your mouth at once and stop babbling about my future, for I don’t believe a word of it.’”

Odd is holding a stick and threatens to hit her if she starts making any prophecies about him. She says she will do so all the same, and that he should listen. She then speaks the prophecy in the form of a poem in three stanzas. In the saga this poem is quoted in prose, which would suggest that it was thought questionable whether or not the listeners (or readers) could still understand poetic language. The prophecy says that Odd will travel from land to land and become famous far and wide, and, what is more, that he will live for three hundred years. The less pleasing part is that he will nonetheless die at home, where they are right now, and that the skull of a horse will be the death of him. The völva starts the poem by warning the young man not to use threatening behaviour against her while she is talking, and she stresses that what she says is the truth. She speaks of herself in the third person, referring to her activity as völva: “the words of the witch/ were wise, you’ll see”.

While the völva is speaking, the young hero Odd leaps up, shouts that the most wretched of old women will pay for her words and strikes her “so hard on the nose with the stick that her blood gushed onto the floor”. She asks for her clothes and says she wants to leave immediately, since this is the first time she has been to a place where she has suffered a beating. The farmer asks her to stay and offers her some fine presents: “She took the gifts, but didn’t stay for the celebrations.”

The völva is called Heiður (Heith), a common name for völvas – cf. “Völuspá” (Prophecy of the Völva) – one meaning being ‘she from the heath/heathen’, i.e. from the wilderness. Other common names are Huld, ‘covered’ or ‘secret’, and Gríma, ‘invisible’ or ‘dark’, which is also a name indicating the limits of acceptability. Prophecy is made in verse; another link between, on the one hand, poetry and, on the other, prophecy and völva. As in Vatnsdœla saga, we see the contrast between old woman and young man, with an emphasis on the hero’s masculinity and on language: Odd twice states that he is “a man”, and he uses force against the woman and drives her away from the farm – and thereby out of the community.

A characteristic of many stories about völvas is that they take place early in the sagas. The völva’s prophecy thus not only foretells the hero’s life, it also lays the foundation for the storyline, and concisely sums up the saga. In both Vatnsdœla saga and Örvar-Odds saga, moreover, the confrontation and dispute with the völva constitutes the first test of manhood. This structure is made explicit in Örvar-Odds saga when, towards the end of his long life (and his long saga) Odd remembers the völva’s prophecy in a verse recalling the earlier episode; he repeats the völva’s words and admits that she was right:

The prophetess

Spoke plainly,

With true words,

But I lacked wisdom.

In Kristni saga (Story of the Conversion) there is a very humorous and, in particular, highly metaphoric story about a direct confrontation between paganism/woman on the one side and Christianity/man on the other. The missionary Thorvald visits a farm in one of the most remote of the western fjords in order to preach Christianity. It is told that while Thorvald is speaking to the people on the farm, the housewife Fridgerd is offering sacrifice inside, so the two hear one another’s words. Thorvald composes a skaldic verse about this episode, complaining that no one could hear him on account of the old giantess who was chanting against him from a “heathen altar”. Their confrontation is verbal. The man and the woman speak both at once. Thorvald calls himself skáld (poet, skald), a word he puts in an elegant semi rhyme with aldinn (old), used of the woman. She is old, pagan and exists beyond the social order, an edda, in opposition to the new skaldic poetry, Christianity and the man’s culture.

Towards the end of Laxdæla saga we are told about a dispute between a Christian woman and an entombed heathen woman. Of the Christian, Gudrun, we are told that she “became a very religious woman”, and that she spent a long time in the church at night saying prayers, accompanied by her son’s young daughter. This granddaughter dreams that a woman of unpleasing appearance comes to her and complains that when Gudrun prays in the church her hot tears fall on the woman and burn her. The young girl tells her grandmother about the dream. The next morning Gudrun has some planks taken up from the part of the church floor where she usually prays, and then the earth below is dug up:

“[T]hey found blue and evil-looking bones, a round brooch, and a wizard’s wand, and men thought they knew then that a tomb of some sorceress must have been there; so the bones were taken to a place far away where people were least likely to be passing.”

For the young girl, who is becoming a woman and a good Christian in an established social order, the image of the völva is a scary warning, whereas for the adult, Christian Gudrun, who kneels on the völva’s grave, it is more of a mirror-image, a picture of her displaced other self.

The young girl has her dream at the same age as Gudrid in the saga about Erik the Red, that is, on the threshold between childhood and adulthood. Her encounter with the völva symbolises young girls’ initiation into the community, and as such can be seen as equivalent to young men’s tests of manhood in the other völva stories.

The dream is significant. It represents a frontier area, a wilderness beyond society. Dream and woman often go together in the saga literature. Women dream, or they appear in the dreams of others – it is a forum in which they have the opportunity to speak, as does the otherwise silenced völva in this story. At the same time, the dream assumes the function formerly undertaken by seid and prophecy, as also demonstrated by the young girl’s dream. In the saga, dream gradually becomes a valuable female channel of expression.

The same process – ridding oneself of a völva – is found in the narrative about Skallagrim and the handmaid Thorgerd Brák in Egils saga Skallagrímssonar (Egil’s Saga). Skallagrim is playing ball with his young son and his son’s slightly older friend; the two lads are on their way to winning. But at sunset Skallagrim is suddenly imbued with such strength that he lifts up the friend and dashes him to the ground so violently that he dies instantly. He then seizes Egil:

“Now there was a handmaid of Skallagrim’s named Thorgerdr Brak, who had nursed Egil when a child; she was a big woman, strong as a man, and of magic cunning. Said Brak: ‘Dost thou turn thy shape-strength, Skallagrim, against thy son?’ Whereat Skallagrim let Egil loose, but clutched at her. She broke away and took to her heels with Skallagrim after her. So went they to the utmost point of Digraness. Then she leapt out from the rock into the water. Skallagrim hurled after her a great stone, which struck her between the shoulders, and neither ever came up again. The water there is now called Brakar-sound.”

The key function of this account, seen from the viewpoint of the saga, is to explain the name Brák in the place name Brákarsund. Woman has become nature. Moreover, metaphorically speaking, it represents the völva, previously elevated so high, but now reduced to thrall and handmaid. She vanishes in the waters, stoned by the furious man as she flees. Brak’s fatal mistake is that she speaks, that she interrupts the man mid-action, and in so doing she crosses the established boundaries. She tries to keep afloat in the heavy sea beyond the social order by swimming – a constantly recurring motif in the literature, where it is usually associated with women. Ironically, she sacrifices herself for one of the first and most famous skalds in Norse literature: Egil Skallagrimsson. Thus she must succumb in order for skaldic poetry to rise. This occurs when Egil is twelve years old. His manhood test follows immediately: he slays his father’s best foreman, and later he sails away from his home in order to conquer other lands.

In the Icelandic sagas, women are only ever killed if they are skilled in magic and seid, the only sphere to which men have no access. As a rule, they are stoned to death or drowned, sent down under the surface of the earth.

Prophecy of the Völva

“Völuspá” (Prophecy of the Völva) is one of the best-known poems in Norse literature – and also the most obscure. The extant material is so deficient that it often seems as if the writer did not really understand what he was writing. Over the years many a scholar has endeavoured to reconstruct and organise the poem, in an attempt to arrive at an epic and more ‘realistic’ text. “Völuspá” is, however, by no means an epic poem. It is a vision in which a völva speaks as if in a trance or dream, with fragmented syntax and with a confusion of metaphors and visual impressions that cannot be pinned down into any rational and unambiguous meaning.

“Völuspá” has traditionally been interpreted as a poem about the apocalypse of pagan culture – or about the end of the world in general. However, it also covers a different and more specific story that is, interestingly enough, told within the same structure as the myth of the völva in other tales: the story about the apocalypse of the pagan female culture.

It is a woman’s voice we hear in “Völuspá”. She either speaks in the first-person, as subject, or in the third-person, as object seen from the outside. This narrator is highly aware of herself as a narrator. In fact, the poem can be read as a meta-poem about a woman who is telling, or rather chanting, a prophecy. The poem is possibly also a völuspá, a real völva-prophecy.

The poem opens with the völva stepping forward and requesting leave to speak: “Attention I bid/ of all the hallowed kindred/ both high and low the offspring of Heimdall.” The poem is placed at the front in the Codex Regius of eddic poems; thus, this female voice which wants to be heard not only opens “Völuspá” but also introduces the entire canon of eddic poetry.

The völva sits so high up that she looks out across the entire world. This is pointed out time after time through the refrain “I see far and wide over all the worlds”. The original meaning of the word spá is ‘sight’ or ‘vision’ (cf. Old High German spahan, formed in the same way as the word ‘vision’, from the Latin video). In the poem, vision is linked to the völva’s speech via a continuous alternation between the story and the situation on a present-tense level. Many a stanza opens with an emphasis on sight as the basis for the prophecy – its source – and the verbs ‘to see’ and ‘to know’ run like leitmotifs throughout the entire poem: “Much more I know, for farther forward I can see”.

The völva is the product of giants, and she is so old that she comes from the wildest chaos before any calendar or the creation of the world. She makes the prophecy/vision at the request of Odin, to whom, at the outset of her speech, she professes: “O Father of seers, at your will/ I shall relate/ ancient tales of the world/ the oldest I know.” She is thus acting as an edda vis-à-vis the new and institutionalised poetry!

In the poem, the völva is in dialogue with Odin, and a conflict arises when Odin tries to avail himself of her knowledge, with which she is reluctant to part. The central stanza in this context is the one in which Odin takes the völva by surprise. “Alone I sat,” she tells us (employing the standard expression for the performance of seid outdoors – and outside the social order). Odin gains power over her by looking into her eyes; and she realises instantly that he wants her insight: “What do you ask of me? Why do you come here?” She tells him everything she knows about the past, the present and the future, and in return Odin gives her presents, bribes her with jewellery:

War-father Odin

gave me rings and necklaces

To gain my lore

and my prophecy.

For I see far and wide

over all the worlds.

Valði henni Herföðr

hringa ok men,

féspjöll spaklig

ok spáganda;

sá hon vítt ok um vítt

of veröld hverja.

The poem sets great store by knowledge, or rather by the transfer of knowledge from woman to man. This is apparent from the völva’s repeated question, the leading refrain in the poem: “Would you know yet more – and what?”

The ending of the poem recalls the story of Brák in Egils saga, with the dark dragon in the same role as furious Skallagrim:

There comes the dark dragon:

The shining serpent flies

up from Dark Mountains;

Flying over the field

Nidhogg bears corpses on his wings.

Now I must descend.

Þar kemur inn dimmi

dreki fljúgandi,

naður fránn, neðan

frá Niðafjöllum;

ber sér í fjöðrum

– flýgr völl yfir, –

Niðhöggur nái.

Nú mun hún sökkvast.

The antithetical metaphors – to rise up and to descend – illustrate what happens when a völva has spoken, when she has poured out her wisdom. She sinks down into the underworld. The female voice is silenced.

The most poetic images in “Völuspá” describe creation in varying visions – and in female negations. It would seem the völva/narrator is best at defining that which is not there: “Years ago, / when Ymir lived, / There was no sand, no sea, / no cold waves; / Earth was not, / nor heaven above, / But only a yawning gap, / and nowhere grass.” The same negative terminology is used to depict the way in which the celestial bodies, personified as him and her, have trouble trying to locate their place in the firmament:

Sun knew not

where her own hall was;

The stars knew not

their own places;

Moon knew not

his own power.

Sól það né vissi

hvar hún sali átti,

stjörnur þa né vissu

hvar þær staði áttu,

máni það né vissi,

hvað hann megins átti.

The repeated use of “knew not” suggests the imperative of knowing, which is again linked to finding a place in life, an identity.

Three gods or goddesses (the tradition is very muddled on this point) find the first man and woman, Ash and Elm, washed up on the shore, in the borderland between wild ocean and established society. “Soul they had not,/ sense they had not,/ Heat nor motion,/ nor goodly hue”, but this they receive from the gods who are already established. According to Snorri’s Prose Edda paraphrasing of the poem, these first human beings are given their identity at the same time as they are given their names and directed to their own place in Midgard. In “Völuspá” creation is closely linked to language and to the act of naming. Nothing has a meaning until it has a name; and the gods use the act of naming to pin down untamed chaos and keep it in place: “Names then gave they/ to noon and twilight,/ Morning they named,/ and the waning moon,/ Night and evening,/ the years to number.”

In a mixture of (much-discussed) images, the völva traces this apocalypse of creation, Ragnarök, to the slaying of the völva Gullveig/Heid in Odin’s hall, as well as to Odin’s spear, which gives the signal for the first feud in the world. The wall around the gods’ fortress is broken, and the feral forces swarm in. The ensuing war is described in masculine terms: “Brothers will fight/ and slay each other”, and there will be “Wind-age, wolf-age,/ until the world perishes”. The female celestial bodies, which had found their place, plunge down from the sky, just like the völva herself at the end of her speech:

Sun blackens, earth sinks into the sea,

Bright stars fall from the sky.

Through these apocalyptic images, the völva glimpses a utopia of a new and better world:

Yet I see emerging from the ocean

Another earth, once more growing green.

Over cascading waterfalls the eagle flies,

And hunts for fish in the fells.

On this new earth she sees a hall “more fair than the sun”, in which “righteous rulers” will meet and live in eternal happiness. Here her vision ends, and the poem returns to the present time with the dragon flying in and the apocalypse breaking out.

Eddic Poetry

Extant eddic poetry is sparse. The greater part is found in a single manuscript, Codex Regius, written around 1270, which is a copy of an older original. The manuscript contains twenty-nine poems, ten mythological lays and nineteen heroic lays. It is not complete. A number of leaves with heroic lays are missing, and in some places words, lines or complete stanzas have been omitted. The text is fragmentary and the syntax is often difficult to understand. Some eddic verses are preserved in the Prose Edda and a very few in other manuscripts of a later date.

By the time the eddic poems were recorded in writing, they were the last remnants of an oral tradition that had been active for many centuries. They are in spoken form, a very old poetic form stemming from a pre-literate culture. The poems are characterised by repetition and litany, language-wizardry pointing back to the origins of poetry in hypnotic and corporeal rhythm – chant, lullaby and work song. Mythological lays deal with how men win wisdom and power, a process often viewed from an ironic perspective using grotesque imagery, and mainly spoken by male voices. Heroic lays treat more of emotions and are characterised by oratorical effects and female voices.

The Winning of Power, Language and Woman

Having silenced the völva in “Völuspá”, Odin recharges his voice. He does this in “Hávamál” (The Sayings of the High One), the poem following “Völuspá” in Codex Regius – and this position in the manuscript underscores that the man’s mál (speech) has taken over the woman’s spá (prophecy, wisdom, vision).

“Hávamál” is a didactic poem of several sections, in which Odin tells about his various experiences and how he has acquired knowledge, usually by means of deceit. On this basis, he gives ethical advice on winning power and on human relations, a kind of code of conduct to which male-dominated society can adhere. The foundation of power is knowledge, and knowledge is language. Command of language, along with the verbs ‘to know’ and ‘to be able to’, is a leitmotif running through the poem. Language is an agency of power. With it you can (and must) act untruthfully: “Thou shalt speak him fair,/ but falsely think,/ And fraud with falsehood requite.” Language is therefore particularly dangerous in the mouths of women who refuse to be controlled. As one of the poem’s most oft-quoted stanzas states:

A man shall trust not

the oath of a maid,

Nor the word a woman speaks;

For their hearts on a whirling

wheel were fashioned,

And fickle their breasts were formed.

With language at their command, women can kill, and it is men they kill:

I saw a man

who was wounded sore

By an evil woman’s word;

A lying tongue

his death-blow launched,

And no word of truth there was.

The women’s tongues are here murderous weapons, whereas weapons are otherwise the exclusive attributes of men who use them to keep the community, including the women, in check. The poem links women’s language to sorcery, this being the major threat to the social order: “Beware of sleep / on a witch’s bosom, / Nor let her limbs ensnare thee.” The language of sorcery is that of incantations and runes, an area belonging to women’s culture, and the two final sections of “Hávamál” address the importance of appropriating them: “Runes you will find, / and readable staves, / Very strong staves, / Very stout staves.” Runes hold a mysterious ritual and a challenge: “Know how to cut them, / know how to read them, / Know how to stain them, / know how to prove them.”

In “Hávamál” the word ljóð (poem) is synonymous with incantations or runic charms. The section “Ljóðatal” (magic songs), with its recurring “I know”, lists the eighteen charms that Odin has appropriated. The poem opens with the speaker boasting of being able to do something the women cannot: “The songs I know/ that king’s wives know not” – and it ends by declaring that these charms should not be passed on to women:

An eighteenth I know,

that ne’er will I tell

To maiden or wife of man,

– The best is what none

but one’s self doth know,

So comes the end of the songs.

In “Hávamál” Odin has commandeered the women’s culture, and the women are not going to be allowed to have it back. The threat of recapture is, however, imminent; and so the poem is, above all, a warning against women and the wilderness they represent. Odin thus addresses his speech exclusively to men.

Odin is the main character in several mythological poems. In “Grímnismál” (Sayings of Grimnir) he arrives in a kingdom, disguised and using a false name; he is taken prisoner and tortured in an attempt to make him tell all he knows. The poem, a monologue, shows a clear connection between language and power. The sought-after wisdom consists of learning the names of the places and of natural phenomena.

Eddic poetry was much concerned with names, and this explains the many litanies of names in this poem, which are often of a hypnotic character and part of an act involving language and ritual. “Grímnismál” concludes with Odin pronouncing his true name. Revelation of the name overwhelms the listener to such an extent that he falls and impales himself on his own sword.

Another poem dealing with name-wisdom is “Alvíssmál” (Talk of Alviss). The poem is a conversation between Thor, the manliest of gods, and the dwarf, Alvis, who has risen to the surface of the world in order to claim a bride: “Alvis am I,/ and under the earth/ My home ’neath the rocks I have.” The bride is Thor’s daughter who had earlier, in her father’s absence, been promised to the dwarf. Problems often arise in the Norse pantheon when Thor is out on his long journeys, because he is the one who keeps the social order together with his hammer and his strength. Thor refuses to give his daughter away unless the dwarf tells him everything he desires to know. Thor’s questions are concerned with names, with what nature and things are called in the various worlds. The dwarf answers all the questions, but he is so eager that he forgets the time. The sun rises and he is turned to stone, transformed into the nature whence he came, while Thor boasts of having outwitted him. Thor is often placed in connection with dwarfs, and this is the only reason that he features here in a role normally taken by Odin. Thor does not usually show any interest whatsoever in wisdom – he represents physical power.

The mythological poetry often features word competitions such as the one we see in “Alvíssmál”. “Hárbarðsljóð” (Lay of Harbarðr) is an abusive contest between Odin and Thor, who stand on either side of a sound shouting at one another. Odin hides behind the name Grey-Beard, whereas Thor is simple enough to give his real name. In the dialogue, which consists of questions and answers, they brag of their own deeds and belittle the other. Odin’s seduction of women is compared with Thor’s battles with giants. Grey-Beard boasts of having conquered “lively” and “wise” women despite their resistance, while Thor retorts that he has felled giants and women of the giants’ race on his journey eastward.

This ‘bride abduction’, in which the dwarf intends to rob the established order of a woman and take her with him out into the wilderness, displays that order’s fear of losing its women to the untamed forces. Furthermore, the father, as patriarch, decides who the daughters will marry. However, abducting a bride in this manner, taking her from society and out into the wilderness, never succeeds – but it does if the motif is turned around: the established gods are more than happy to fetch a woman from the wilderness and integrate her within their community.

Thor’s hammer plays a crucial role in the highly grotesque “Þrymskviða” (The Lay of Thrym). Thor wakes up one morning to find that his hammer is missing. The giant Thrym has stolen it, and he will only return it in exchange for the goddess of love herself, Freyja, for his wife. Freyja refuses, and the gods hold a meeting; they propose that Thor dresses up in women’s clothing, disguising himself as Freyja. He protests, because he does not want to be called argr, or homosexual. However, as Loki points out, there is much at stake: “Be silent, Thor,/ and speak not thus;/ Else will the giants/ in Asgarth dwell/ If thy hammer is brought not/ home to thee.” It is interesting to note that Thor is silenced before he is dressed up in bridal clothes. With gems across his breast and in a dress flowing to his knees, he sets forth to the wedding in Jotunheim, accompanied by Loki disguised as a maid servant. Thor nearly gives himself away time after time; he drinks too much, eats too much and is in every respect unlike the giants’ expectations of Freyja. The ploy works, nonetheless, and the phallic significance of the hammer is emphasised when it is placed on “the maiden’s knees” during the wedding. Thor gets back what he (and his community) had lost. First he kills the giant Thrym and next “the giant’s sister/ old he slew”, who feels both “a stroke” and “the might” of the hammer in the final stanza of the poem.

Cases of transvestitism, such as the one described in “Þrymskviða”, occur several times in eddic poetry and in the legendary tales of Icelandic prehistory, where they are usually connected to the everyday world and are depicted in grotesque metaphors addressing issues of gender and gender roles.

The god Loki is interesting in this context. He is both man and woman, but out in the community he plays the role of man. “Lokasenna” (Loki’s Quarrel) takes the form of a discourse between Loki and the other gods during a feast. Loki has got himself so drunk that he discloses all the gossip he has heard about those present. Gossip is unrestrained talk, and here it tells of body and sex. The goddesses, according to Loki, are nymphomaniacs and the male gods are homosexuals. This dialogue would never have taken place had Thor been present instead of being in the eastern region crushing the giants. Just as the gathering is breaking up, however, he returns home from his travels and abruptly terminates all talk: “Unmanly one, cease, / or the mighty hammer, / Mjollnir, shall close thy mouth.” Loki is forced to leave the feast, and is expelled from the community for all time.

“Skírnismál” (Sayings of Skírnir) is also about the theft of a bride, but from a different perspective than that of “Þrymskviða” and “Alvíssmál”. The prose prologue tells us that the god Freyr is sitting in Odin’s throne, Hliðskjálf, and is looking out over all the worlds. In Jotunheim he sees “a fair maiden, as she went from her father’s house to her bower”. He is beset by gloom, and ends up confiding in his attendant Skírnir, who agrees to undertake the dangerous journey into the wilderness to fetch the woman. Skírnir asks for the horse that can break through the flames surrounding the woman’s hall, and he wants to take Freyr’s sword. With this sword “that fights of itself/ Against the giants grim,” Skírnir will win the woman. The sword thus has a twofold and clearly phallic meaning. The image of flames blazing around the maiden’s abode appears time and again in eddic verse. Fire designates the transition between the community and the women’s space, and it is dangerous for men to cross through it.

Skírnir arrives at Jotunheim, but the maiden Gerth refuses to go with him, and a fierce dialogue ensues. Skírnir starts by trying to bribe her with, for example, jewellery, but to no avail. The next step is to make threats, and Skírnir resorts to the sword:

Seest thou, maiden,

this keen, bright sword

That I hold here in my hand?

Thy head from thy neck

shall I straightway hew,

If thou wilt not do my will.

She refuses to bow to force: “For no man’s sake/ will I ever suffer/ To be thus moved by might.” Skírnir takes no notice of her words, and the poem continues with a long list of curses. This messenger from the male community threatens physical violence as well as death: “I strike thee, maid,/ with my magic staff,/ To tame thee to work my will.” He threatens her with imprisonment, hopelessness, loneliness, sorrow, torment and all manner of madness. She will marry a three-headed giant or no man at all, and she will drink goat urine. Eventually, when he lists the adversities in runic charms, she gives in and promises to meet Freyr in the forest nine nights hence.

“Skírnismál” is a poem about force, although literary history has interpreted it as a love poem. This identification with male desire and disregard of the woman is backed up by Snorri in his rewriting of the poem in Edda, where the dialogue between Skirnir and Gerth has been omitted, leaving a simple love story.

Sigurd Fafnirsbane is the central male hero of heroic poetry. A number of poems record his route to manhood and power. One of them is “Sigrdrífumál” (Sigrdrífa Sayings), which, in its material and its many litanies of wisdom, is somewhat suggestive of mythological writing.

The poem’s prose introduction tells us that Sigurd (who has just slain the dragon Fafnir and usurped his gold) rides up a mountain, where he sees “a great light, as if fire were burning, and the glow reached up to heaven.” When he gets closer, he sees a tower of shields with a banner flying on top. He enters the tower and sees a man lying asleep in full armour:

“First he took the helm from his head, and then he saw that it was a woman. The mail-coat was as fast as if it had grown to the flesh. Then he cut the mail-coat from the head-opening downward, and out to both the arm-holes. Then he took the mail-coat from her, and she awoke, and sat up and saw Sigurth […].”

This woman is the Valkyrie Sigrdrifa. Because she disobeyed Odin, the god “pricked her with the sleep-thorn” and vowed that she should marry and no longer be victorious in battle. Valkyries often appear in eddic poetry. They are Odin’s maidens; they participate in battle and, as here, can decide which of the combatants will fall on the battlefield. Unlike the married woman, who has her fixed place defined by the social order, the Valkyries are supernatural and can fly. Many female characters in the heroic poetry – such as Brynhild in the lays of Sigurd, Svava in “Helgakviða Hjörvarðssonar” (Lay of Helgi Hjörvarðsson) and Sigrun in “Helgakviða Hundingsbana I + II” (The First Lay and the Second Lay of Helgi Hundingsbane) – are at one and the same time ordinary women and supernatural Valkyries. This dual role can already be seen in the mythological Valkyries: when they return home from the battlefield, they brew mead for, and wait on, the dead heroes sitting at table in Valhalla. In “Völundarkviða” (The Lay of Volundr) the marital woman’s role becomes so intolerable for the three Valkyries that they fly away from their husbands, never to return.

“Sigrdrífumál” is the speech of the Valkyrie Sigrdrifa. The opening is reminiscent of the story of the völva awakened from the dead: “What bit through the byrnie?/ how was broken my sleep?/ Who made me free/ of the fetters pale?” Sigurd introduces both himself and his sword, and Sigrdrifa gives him a horn full of mead. She then hails the world in an image of rebirth:

Hail to the gods!

Ye goddesses, hail,

And all the generous earth!

Give to us wisdom

And goodly speech,

And healing hands, life-long.

A number of eddic poems link the healings arts with women. In “Fjölsvinnsmál” (The Sayings of Fjölsvinnr) the woman Menglöð lives on the healing mountain, and nine goddesses sit at her knee, each representing a healing art. Like Sigrdrífa, Menglöð is surrounded by flickering flames, and she too is waiting for a man: “Long have I sat/ on my loved hill,/ day and night/ expecting thee.”

This is an androgynous vision; it is the same as that of the völva in “Völuspá”, but it is unlike Odin’s in “Hávamál”, which is addressed exclusively to men. Sigrdrifa hails both genders, and she asks for language, wisdom and healing arts for Sigurd and herself alike. Sigurd asks her to teach him wisdom, and she starts to pass on everything she knows. While she speaks, she offers him mead full of charms, spells and runes. The poem comprises litanies of runic wisdom and advice. In the first part of Sigrdrifa’s speech she teaches Sigurd seven runes, including thought-runes for wisdom, speech-runes for eloquence, and branch-runes for the art of healing, and, she says, he must “birth-runes learn, / if help thou wilt lend, / The babe from the mother to bring”.

After the list of runes, Sigrdrifa stops and asks if Sigurd wants “speech or silence”. He wants her to go on, and she then gives him eleven numbered counsels, the hypnotic rhythm of which feels like a magic formula. Moral counsel is mixed with everyday wisdom and practical instructions such as how to wash a corpse.

Sigurd awakens the valkyrie by using a form of violation that is reminiscent of Odin’s conquest of Gunlad in the myth of the skaldic mead. Both women live in the wilderness, dwelling in or on a mountain, and they have a hoard of wisdom that they pass on in mead. “Sigrdrífumál” is the last poem in the series of lays dealing with Sigurd’s youth. His conquest of the Valkyrie completes his test of manhood. She experiences the episode as an initiation into the role of woman: “Long did I sleep,/ my slumber was long,” she says once the young hero has awakened her, cut open her armour with his sword and made her a woman.

The end of “Sigrdrífumál” marks the beginning of the Great Lacuna in the extant manuscript. After her encounter with Sigurd, she returns – according to Völsunga saga, which identifies Sigrdrifa as the Valkyrie Brynhild – to the house where she lives with her maidens, and sits “overlaying cloth with gold, and sewing therein the great deeds which Sigurd had wrought”. The androgynous world she hailed at her rebirth has now become the man’s world alone.

Women and Tears

Norse heroic poetry deals with the consequences of the men’s heroic deeds. Weeping women run through the entire oeuvre like a leitmotif; grátur (grief/weeping/lament) is the main genre. The designation grátur occurs in the poetry itself in “Oddrúnargrátr” (Oddrún’s Lament), the last stanza of which defines the genre as such: “Oddrun’s lament/ is ended now.” In “Guðrúnarhvöt” (Gudrun’s Incitement) the genre is called tregróf (enumeration of sorrows/lament), and it addresses men and women alike: “May nobles all/ less sorrow know,/ And less the woes/ of women become,/ Since the tale of this/ lament is told.”

‘Lament’ is a category of elegy reserved for women. The women’s elegies of heroic poetry are characterised by autobiographical retrospection, the lament being rousing, accusing, imploring and full of curses, and expressed in strongly sensual terms. In “Guðrúnarkviða forna” (Second Lay of Gudrun), “Guðrúnarkviða fyrsta” (First Lay of Gudrun) and “Oddrúnargrátur” (Lament of Oddrun), the lament carries the entire poem; in other poems it occurs only in parts, fragmentarily.

In “Guðrúnarkviða forna” Gudrun tells her tale, starting out as a happy young maiden in her mother’s care and ending up as Atli’s wife. Sorrow enters her life when her brothers kill her first husband, Sigurd. The only living being with whom she can share her sorrow is the horse Grani.

Weeping I sought

with Grani to speak,

With tear-wet cheeks

for the tale I asked;

The head of Grani

was bowed to the grass,

The steed knew well

his master was slain.

In this stanza Gudrun recalls her own earlier tears, thus creating a lament within a lament. The same double-lament occurs at another point in the poem, when Gudrun tells of her mother’s tears: “Weeping Grimhild / heard the words / That fate full sore / for her sons foretold.”

When Gudrun’s brothers have confirmed that they have killed Sigurd, she goes into the forest to search for the remains of his body: “From him who spake / I turned me soon, In the woods to find / what the wolves had left.” She sits next to Sigurd’s body for a whole night, alone in the desolate wilderness, surrounded by croaking ravens and howling wolves. The description is full of horror, but she sheds no tears: “Tears I had not, / nor wrung my hands, / Nor wailing went, / as other women.”

Gudrun does not return to the society she left. After five days travelling through the wilderness she arrives in another community, in Denmark, where she stays with Thora, daughter of Hakon. Here she stays hidden away until her mother finds out where she is living and comes to fetch her. Her mother plays the patriarch’s game and wants Gudrun to marry Atli. Mother and daughter quarrel, their dispute recalling that between Skírnir and Gerth in “Skírnismál”. The mother gives Gudrun a drink, a potion causing her to forget – and so Gudrun capitulates. Forced marriage, such as this one, is a common motif in both the eddic poetry and the legendary tales, where it most often leads to the husband’s death.

“Guðrúnarkviða fyrsta” starts from the point in the “Guðrúnarkviða forna” half-stanza where dry-eyed Gudrun sits watch besides her dead husband, Sigurd, in the forest. Gudrun is now sitting alongside Sigurd’s body in a closed room, with women around her, and she cannot weep. Men try to soothe “her heavy woe”, and women console her with tales of their own sorrows. The refrain “Grieving could not/ Guthrun weep”, is heard after each of these attempts. Once Gudrun’s sister has removed the shroud from Sigurd’s corpse, however, she gives way to her grief. “Then Guthrun, daughter/ of Gjuki, wept,/ And through her tresses/ flowed the tears.” At the same time, her language is set free and she begins to speak.

The prelude to tears is rememberance of a beloved husband, who is described in nature metaphors and elevated above other men: “So was my Sigurth / o’er Gjuki’s sons / As the spear-leek grown / above the grass.” Lament is mixed with accusation which, by virtue of repetition, assumes the character of incantation:

Giuki’s sons have caused,

Giuki’s sons have caused

my affliction,

and their sister’s

tears of anguish.

“Atlakviða” (The Lay of Atli) tells the story of how Gudrun takes revenge on Atli for having her brothers killed. The poem is told in the third person and takes the form of dialogues between several characters. Lament is a central motif, and is seen as a contrast to the revenge. Everyone weeps, with the exception of one person: “all wept save Gudrun, / who never wept, / or for her bear-fierce brothers, / or her dear sons”. She does not weep; she acts. She kills the sons she has borne to Atli, and serves him their flesh at the feast. She then kills Atli with a sword, having first paralysed him with a potion. She burns down his hall and all within, an image recalling the apocalypse in “Völuspá”: “The old structures fell, / the treasure-houses smoked,/ the Budlungs’ dwelling.”

The same events are described in “Atlamál” (The Greenlandic Lay of Atli). Initially, when the brothers visit their brother-in-law Atli, Gudrun tries to reconcile the contending parties. When this does not succeed, she joins in their battle, shedding her woman’s role in a mighty metaphor: “With necklaces fair, / and she flung them all from her, / (The silver she hurled / so the rings burst asunder.)” She later explicitly criticises male society: “But the fierceness of men / rules the fate of women.” She utters these words during her final dispute with Atli, and they are the motivation for her terrible deed.

“Guðrúnarhvöt” opens with Gudrun working herself up to revenge, but the poem ends in tears. The prose introduction tells us that Gudrun went down to the sea-shore after killing Atli. She waded out into the water in order to drown herself, but she could not sink. Instead she crossed the firth to another country, where the king married her. The poem has a framework in which an ‘I’ carries the tradition of Gudrun’s elegy, but the poem is also Gudrun’s autobiography. It reports on many of the same events as “Hamðismál” (The Lay of Hamdir), but from a different perspective. Both poems open with Gudrun inciting her sons to avenge her daughter Svanhild, who was killed by order of her husband, trampled to death under the hooves of horses. In “Hamðismál” Gudrun uses the agency of lament; her sons set forth and the story goes with them. In “Guðrúnarhvöt”, however, the story stays with Gudrun, who, having sent her sons to their death, sits weeping in the forecourt of her house:

Weeping Guthrun,

Gjuki’s daughter,

Went sadly before

the gate to sit,

And with tear-stained cheeks

to tell the tale

Of her mighty griefs,

so many in kind.

She weeps her sorrows in two stanzas, but at the beginning of the third her voice is silenced by the tradition-bearing first person narrator; all he writes is: “Many woes I remember.” In scholarly editions of the poem, this stanza ends in a series of dots, indicating the lacuna. In other editions it has usually been omitted entirely. There is no way of knowing how many stanzas are missing. In the next surviving stanza the scene has changed. Gudrun is talking with the dead Sigurd, who has come to fetch her, and she prepares for the pyre: “Let the fire burn/ my grief-filled breast.”

Rebellion and Work Song

“Gróttasöngr” (Song of Grótti) is the only surviving work song of the eddic canon. It is not included in Codex Regius, but can be found in the Prose Edda. The narrative outline of the story tells us that Danish King Fródi buys two giant maidens who are strong enough to turn the enormous grinding mill called Grótti. At first they grind gold and peace and prosperity for the king and his realm. But the king allows them no rest, and so they “then sang the song called Gróttasöngr”, and they did not stop until they had ground an army against King Fródi – and he is slain.

“Gróttasöngr” is more a poem about work songs than a work song in its own right. It is also a poem about the tyranny of patriarchy and women’s rebellion. The metaphors are based on the contrast between men with power and women in slavery. A large proportion of the poem consists of the giantesses’ one-sided ‘dialogue’ with their tyrant, in which they threaten him via their magic song: “Wake thou, Fródi!/ wake thou, Fródi!/ if thou wilt listen/ to our songs/ and sagas old.”

The giant women sing their song together or by turns while they work the grindstone:

They sung and swung

the whirling stone.