The postwar generation of writers in Finland sought new moral and esthetic values in an atmosphere of cultural pessimism and loss of faith. The young poets felt an enormous need to break the ties to the classical lyrical tradition and the rhetorically empty language from before WWII.

The then-young Paavo Haavikko (born 1931), later a giant within Finnish literature, became the pioneer of Finnish lyrical modernism with his debut Tiet etäisyyksiin (Road into Distance), 1951. Haavikko’s bold, ambiguous metaphorical language, ironically mythical style, and historic associations radically divided him from the prevailing anachronistic, and rigid, rhetorical tradition.

The impulses particularly came from Swedish modernism (Erik Lindegren and Karl Vennberg) and influenced poets such as Lasse Heikkilä and Viljo Kajava, while impulses from French poetry reached Pentti Holappa, Olli-Matti Ronimus, and Tyyne Saastamoinen. Anglo-Saxon modernism was introduced via translations of T. S. Eliot and Ezra Pound.

Tyyne Saastamoinen (born 1924) is a subjective, intellectual poet, whose poems shift from a restless search for security to meaninglessness, chaos, and an ambivalent rootlessness. Another important 1950s modernist, Eeva-Liisa Manner, is a distinctive poet who transfers her private mythologies to a universal plane. The intellectual, linguistically austere Mirkka Rekola secretly wants to be integrated into the world, while Helvi Juvonen (1919–1959) unites a religious seeking with a grotesque poetic landscape, torn trees and roots, still waters, and moulding leaves, and mixes modern imagery with traditional techniques. Maila Pylkkönen, Mirkka Rekola, and Tyyne Saastamoinen taken together form a connection between the generations of the 1950s and the 1960s through their contemplative monologues.

Certain signs of dissolution of linguistic conventions, first and foremost in the stagnant formal poetry, were found as early as in the 1940s with poets like Sirkka Selja, Aila Meriluoto, and Eila Kivikkaho. Sirkka Selja’s lyrical identity already shows in Taman lauluja (1945; Tama’s Songs), in which an oriental holism, life mysticism, and vitality unite with transcendentalism, a communication via animals and nature. Aila Meriluoto’s debut collection Lasimaalaus (1946; The Glass Painting) expressed the disillusion that later characterised the modernist generation. Even stylistically, a number of poems contained modernist elements.

Lack of illusions, scepticism, and relativism entered the Finnish modernist prose with Marja-Liisa Vartio, Paavo Haavikko, Veijo Meri, and Antti Hyry. While the prose of Antti Hyry represents objective minimalism, Veijo Meri’s represents grotesque irony and apparently simple intrigue, while Paavo Haavikko stands for intellectual paradox, polemics, irony, and the absurd. With Marja-Liisa Vartio the modernist narrative consists of folklore, mythological-symbolic traits, and a Beckett-like absurd dialogue, which via interminable neurotic conversations about seemingly everyday matters traces features of imprecation and security in women’s shut-in lives.

Common traits in modernist prose in Finland are the linguistic rebellion against earlier traditions, the shifts of point of view, and an ironic style that may slip into parody. Breaches of syntax are frequent. The novelty is that even the non-dramatic incidents are also depicted accurately and take on a symbolic value, and that reality is described as more complex than hitherto.

The modernism within the poetry of the 1950s has, in spite of a certain aesthetic mannerism, kept its vitality and actuality mainly because of the linguistic and formal control, a certain incontestable competence and maturity.

Elisabeth Nordgren

The poet of Metamorphoses

Eeva-Liisa Manner (1921–1995) had her debut as a poet during the Second World War with Mustaa ja punaista (1944; Black and Red), which reflects the events of the war and deals with the loss of her home town of Viborg on the Karelian Peninsula. The next collection, the dreamily erotic Kuin tuuli tai pilvi (1949; Like Wind or Clouds), plays on the Romantic lyrical tradition. Through its richness of expressions, Eeva-Liisa Manner’s early poetry was distinct – both when it came to horror and to Eros – from the Finnish 1950s modernism, which was a visual and intellectual invention inspired by Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot.

In solitude in Tavastland, Eeva-Liisa Manner wrote her break-through, the novel Tyttö taivaan laiturilla (1951; The Girl on the Pier of Heaven), the collection of short stories Kävelymusiikkia pienille virtahevoille (1957; Prom Music for Small Hippopotami), and the poetry collection Tämä matka (1956; This Journey). With Tämä matka she achieves the new modernism of the 1950s, but she also exceeds it. This collection of poems caused her to be seen as one of the foremost in the otherwise male-dominated new generation of poets.

The environments and landscapes in Eeva-Liisa Manner’s poetry relate to the lonely beaches of summer in Tavastland’s woods, the prosperous industrial town Tammerfors, and from the middle of the 1960s also the little southern Spanish town Churriana. The description of Finnish nature, intellectual milieus, and the Latin way of life originate there. But beyond all this lies a still deeper source of memories and longing, the Viborg of her childhood, whose culturally rich atmosphere lives on in metaphors and intimations.

The childhood experiences in the lost hometown are a fruitful foundation for the writings, and Eeva-Liisa Manner gladly seeks out similar environments, among other places in Spain. In spite of belonging on the Karelian Peninsula and her strong identification with everything Karelian, her ancestry reaches back to Nyland’s Finland-Swedes and to Savolax and Tavastland. She has a multicultural background similar to that of the pioneer of Finland-Swedish modernism, Edith Södergran. In her poems Eeva-Liisa Manner often creates seemingly serial cultural, natural philosophical, or technological visions. She found support for her points of view in the philosophy of Spinoza, Simone Weil, Heidegger, Wittgenstein, and C. G. Jung, as well as in the oriental philosophers. With the modernist breakthrough Tämä matka, written when she was thirty-five years old, her literary activities within drama, prose, essays, and translation expand to become a very important and valuable cultural contribution.

In 1968 the focus in essays and criticism moved from Finnish poetry to translations of foreign prose and drama. The extensive translation included works by Georg Büchner, Yasunari Kawabata, Herman Hesse, Václav Havel, Konstantínos Kaváfis, and William Shakespeare.

Magic and the Body

Tämä matka depicts the existential schism in which an ego in crisis can “no longer” and “not yet” come into being in a new language. “Speaking of grief presupposes tact, but what if one has lost everything but grief?” The condition of infinity, symbolised by fossils, snails, miniature ornaments, houses, and rooms, forms the basis for grotesque metamorphoses that grant access to pleasure (“to eat”) or fear (“to be eaten”). Eeva-Liisa Manner touches upon organic as well as inorganic conditions, evil and good, to build a primary, bodily integrity, a magical order.

Tämä matka is culture critical and nature philosophical. In the poem “Descartes”, monistic and mystic thinking is opposed to the rational culture. In the musical poems “Bach” and “Kontrapunkt” (Counterpoint), a new order flows out of the core of the heart, and the richness of existence is shown in micro-cosmos. A metaphysical peace gives openness and strength as in the animals – sacred to Eeva-Liisa Manner. The suite of poems “Kambri” (Cambrian) expresses the lost connection between man and nature. Just like in “Lapsuuden hämärästä” (From the Darkness of Childhood), this loss is coupled with a primary loss of the body. The little girl experiences her world as magical and orally erotic, a dimension that is lost through upbringing. The male, hierarchical, and authoritative order of society, which through religion has shackled and denied the corporeal and thereby amputated women, is accused in the suite of poems “Oikeusjuttu” (“Trial”).

With the collection of nature poetry Niin vaihtuvat vuoden ajat (1964; Thus the Seasons Change), she leads the modernism of the 1950s into an oriental-inspired impressionism of nature. The erotic and grotesque, characteristic of her previous poems, is now openly expressed in her drama and prose, only to merge into a combination of the tragic and the comic by the end of the 1960s.

The kestrel, a shrill shriek,

the death of the echo, pause, silence,

the wind’s feathers fall,

and behind the gate of silence

terrible knowledge

like a full moon through the trees of the wood,

like Agamemnon’s moon

through a bloody wood.

(Eeva-Liisa Manner: Kuolleet vedet (1978; Dead Water)

The Poetics of Contemplation

Through her many essays and critical works, Eeva-Liisa Manner creates a personal artistic theory influenced by European modernism. She stresses the limitations of linguistic expression and emphasises the significance of inspiration and strong emotions for the creative process. She is an engaged modernist who places importance on self-reflection and analysis of the human condition, and questions hierarchies and classifications. She does not shy away from using grotesque, ironic, or lyrical-tragical elements to circumvent the reflexivity of language. In particular, the plays she has written about the miserable conditions of life for women formulate her point of view: that language covers up an abhorrence at the random freedom of human life. In the play Poltettu oranssi (1968; Eng. tr. Burnt Orange), she depicts the breakdown of a psychic, “mad” girl who has her own language.

In the spring of 1969, Eeva-Liisa Manner’s play Poltettu oranssi (1968; Burnt Orange) was performed for the first time in Tallinn in Estonia. In Finland the play was never off the repertoire on Tammerfors Arbetarteater (Tammerfors Worker’s Theatre) during the 1970s. Tauno Marttinen has composed an opera based on the play.

Finnish poetry of the 1960s opens itself to society, city life, and internationalism. Eeva-Liisa Manner’s collection Fahrenheit 121, 1968, responds to the new situation and its demand for political commitment by questioning free will. Fahrenheit 121, which starts with an experience of alienation, defines the social and historical conditions of the human as ‘impossible’. This is a poetry whose driving force is the love of humanity, whether treating of the poor of Spain, the wars in the Middle East or Vietnam, or the consciousness of the ego as a sort of erotic condition.

A major theme in the works of Eeva-Liisa Manner is the opposition to totalitarianism, such as in the collection Jos suru savuaisi (1968; If Sorrow Smoked) about the rebellion in Czechoslovakia, or the novel Varokaa, voittajat (1972; Be On Your Guard, Victors!), and the Poland poems she published in the 1980s.

Fahrenheit 121 culminates with the poem “Kromaattiset tasot” (The Chromatic Steps), which is a broadly existential philosophical cycle of poems about poetry and emptiness. The poet, who questions the basic choices of existence, lowers herself further still into the abyss of emptiness. The experience of emptiness is very corporeal, female, and erotic despite the vertiginous cultural journeys into philosophy, mysticism, and modern physics.

But this isn’t important, I

don’t take myself seriously,

I take the emptiness seriously.

That is the subject. I am the verb:

I constantly scratch, in spite

of slowly changing,

my opinions against the screen of Emptiness.

Eeva-Liisa Manner: “Kromaattiset tasot” (Chromatic levels), Fahrenheit 121

Eeva-Liisa Manner’s early interest in Heidegger during the middle of the 1960s gives her the opportunity to connect language, existence, and culture into an ethical whole, a fighting humanism. She also becomes a significant playwright and begins to introduce foreign prose and films, predominantly from the Latin and Japanese cultural spheres.

Unrestrained Cats and Rain People

In Eeva-Liisa Manner’s work of the late 1960s, an androgynous cat with carnevalian traits starts to make an appearance, just like the hippopotamus of previous poems inspired by the Jungian animus symbol, the horse. The cat first appears in the absurd miniature drama Sonaatti (preparoidulle pianolle) (1969; A Sonata (for the prepared piano)), in which the little girl, “the little patricide”, explains that she killed her father because he killed her cat. Eeva-Liisa Manner’s rhyming, tantalising Kamala kissa (1976; The Terrible Cat), a figure inspired by T. S. Eliot’s book of cats, recurs occasionally in her works. In Katinperän lorut (1985; Nonsense from the Cat City), the cat is dressed in Finnish folk poetry’s trochees, and chases “drunk heroes”, who are “mad having drunk the brew of the devil, till they drown in the vat of evil”.

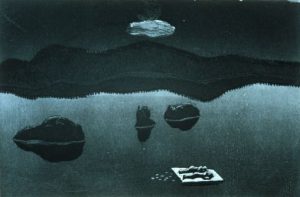

A parallel work to Kamala kissa is the collection Kuolleet vedet (1977; Dead Water), characterised by simplified imagery based on light, darkness, water, and earth. Here, the criticism of western civilisation begun in Tämä matka culminates in a marked ecological message. Apart from the theme of death, there is a cautious trust in the “Rain People” who realise their place in the natural cycle. Eeva-Liisa Manner sees it as the task of the author to listen to what has been forgotten in life, to convey the insight that life and poetry presuppose myths, in which light can be dark and vice versa.

In her essays, Eeva-Liisa Manner has several times stressed that the finest poem opens a gate to the ambiguous and mysterious space and to silence. And this is where the artist’s real task begins: to see and hear more, to say what cannot be said, and to express what cannot be expressed. The art of language reaches beyond normal communication. Basically, to write is to encircle the unsayable, to articulate it in poetry and culture, in spite of writing being peripheral to the centre of the silence.

Tuula Hökkä

The Birds of Death and Dream

When Marja-Liisa Vartio (1924–1966) died in 1966 she was just forty-two years old, and a year later her last novel, Hänen olivat linnut (1967; The Birds Were His), was first published. It is her darkest and most complex work. Chronology has been dissolved, past and present are mixed, just as the memories and dreams of the characters; the tragic merges with the grotesque.

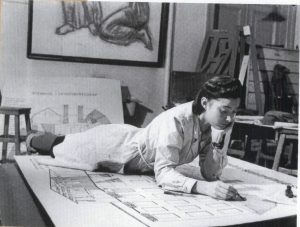

Marja-Liisa Vartio was a master of Art History, Comparative Literature and, Folklore Research.

The focal point of it all is an old disaster: a fire in a parsonage. They managed to rescue the parson’s large collection of stuffed birds, which he had inherited from an uncle. These dead birds are now his widow Adele’s sole purpose in life. After the fire her husband asked Adele not to continually imagine herself to be the Phoenix; according to him, she was just a high-strung woman who could not relate normally to her pregnancy.

Adele and her servant girl Alma make an odd couple, each other’s opposite and complement, and their relationship has erotic undertones. Adele is a kind of Leda without swan in a frustrating marriage, where her husband’s primary interest in life is shooting and stuffing birds. The younger and unmarried Alma reeks of earthy fertility and is strongly attractive to the weak men of the novel. She is often compared to animals, including a bear, or is called a ”vestal virgin”, but also “man-woman”, androgynous.

Narrative rituals have passionate or even therapeutic significance for these women. Adele wants Alma to tell the same stories over and over again, always with the same wording; particularly the tale of the stuffed swan that Adele dreams of having. Her second desire is to get Alma to pretend to be a bull in the act of mating.

Marja-Liisa Vartio’s central themes are united in the bird symbolism: the dream of freedom, the ability to fly.

Marja-Liisa Vartio began her writings as a poet and writer of short stories with dream-like fantasies and surreal visions. She has often been compared to Maria Jotuni. Both have ruthlessly described the conditions of life for women and their relationships to men, but in Vartio’s work the pessimistic keynote is softened by humour.

On her fortieth birthday Marja-Liisa Vartio wrote in her diary that, among other things: “All the practical things stress my nerves; they are worn out, I am continually agitated, everything throws me off balance. If I only knew what balance is. I try to write […] I hear lines, but just lines, I cannot move my characters from one situation to another. I have a very small literary talent, nothing at all. A couple of poems, a few dream short stories, ‘Se on sitten kevät’ (‘Now it is Spring’), that is all. I am stiff and untouchable, everything has become immaterial to me, in a dangerous way I have lost my zeal, the interest in the world, the so-called ambitions do not attract me […]. The only thing I wish for is peace of mind, I am very tired, just a healthy sleep to live for the children […].”

Paavo Haavikko: Yritys omaksikuvaksi (1987; Attempted Self-Portrait)

Se on sitten kevät (1957; Now it is Spring) depicts a brief relationship between two rootless, middle-aged people. They work on a farm, she tending the cattle, he as a farm hand. Her sudden death ends their plans of a shared future and a home of their own. In his lonely grief after having lost the strong independent woman, the lax and weakened man, incidentally called Napoleon, goes through a process that matures him.

A young woman’s dawning sexuality and liberation from her parents is the theme of Mies kuin mies, tyttö kuin tyttö (1958; Man as Man, Girl as Girl). A young woman is expecting a child with a married man. Through extensive use of inner monologue, the novel depicts her lonely fight against the unwanted pregnancy and her desperate attempts at abortion in minutiae. Her father, in particular, dismisses his ‘fallen’ daughter, who finally takes responsibility for her actions and moves away from home.

The sexual act makes the girl conscious of her body and femininity, but her relationship to sexuality is ambivalent. After the first intercourse she feels like an animal, and in the darkness of the night she creeps to the bathroom to wash herself clean. She is sexually active and does not blame the man for anything, but at the same time she is ashamed of her own passion and growing body.

Both novels are written in a terse, establishing style that was characteristic of the Finnish prose of the 1950s. The writer does not comment on the actions of the characters, but allows the reader to draw his or her own conclusions. The almost ascetic narrative is broken by passages of lyrical style, often tied to nature, or by strongly visual scenes and dreams that often function as erotic symbols. Mythical material is used in the same way: one may find the Biblical Ruth, Mary Magdalene, the Fall of Man, and the Orpheus and Eurydice myth of antiquity. In the matter of narrative technique, Marja-Liisa Vartio opened new avenues, not least with her free use of ancient myths.

In her later novels, the style becomes more embellished and the significance of dialogue grows, and humour and irony become more prevalent. Kaikki naiset näkevät unia (1961; All Women have Dreams) depicts a homemaker with three children in a Helsingfors suburb. She feels without identity as her husband’s wife. All her plans and attempts come to nought, whether pertaining to her own money earned through painting porcelain or to a house with a view of the woods.

When Mrs Pyy finally consults a psychiatrist, who suggests a vacation in the South, she chooses Italy, being interested in art. She particularly looks forward to seeing the Sistine Chapel and Michelangelo’s frescoes, specifically his sibyls; according to her husband, she resembles the sibyl Delphica. When she drifts exhaustedly along with a troop of tourists through the Vatican and finally takes a rest on a bench, she happens to overhear that she is actually in the famous chapel without even having noticed. The expected great experience fails to materialise.

Blindness, symbolically seen as the inability to achieve insight into one’s own situation, was a motif already in Vartio’s previous novel, Mies kuin mies, tyttö kuin tyttö. The girl goes to the cinema, but does not understand the images she sees. It is Jean Cocteau’s avant-garde movie Orphée (1950; Orpheus), which she simply lacks all the prerequisites for understanding. Mrs Pyy, too, is blind: she does not even recognise her own reflection.

Mrs Pyy has always waited in vain for a message from her lover: “She had waited for him, the man, to tell her, the woman, who she was. The woman wanted to see herself through the eyes of the man, as if only through his eyes could she see herself.” Mrs Pyy’s eyes are finally opened when she sees a peddler trick ignorant female tourists by selling cheap cameo jewellery far too expensively.

During the 1950s a number of war novels were published in Finland, and Tunteet (1962; Emotions) can be seen as a different war novel, experienced and narrated by a woman at home. It is also a love story and a psychological study of the ’war’ that goes on between two essentially different young people.

Recently graduated from school, Inkeri gets the soldier Hannu to teach her Latin before she starts university. In everything, he takes on a teacher’s position towards her: this lively girl from the country must be ‘educated’, in fact changed completely. Hannu the academic is not for nothing from the old cultural capital of Åbo. Sweet music ensues; the youths get engaged and finally marry, but their conversations often end in tragicomical misunderstandings, because they find it hard to express their feelings in words, and they often choose letters instead. By the end of the book, Inkeri sits in the train on her way home after one year of failed studies. She leafs through her notes from the lectures on aesthetics, about Goethe and the definitions of the bildungsroman, without understanding what she is reading. She writes to Hannu that she feels she has matured during her first year at the university.

In the dream story “The Vatican”, Marja-Liisa Vartio depicts a woman’s pilgrimage to receive the Pope’s blessing. “With flowers and ears of corn you return, from whence you have come.”

Tunteet can also be seen as a parody of a bildungsroman. In the epilogue we briefly hear of Inkari’s fate: six years later she is a housewife with three children, while Hannu still studies. When she hears her old room-mate on the radio, she turns it off. During their time at university this roommate compelled Inkari to help her get an abortion because a child would have destroyed her acting career. Neither Inkari nor Mrs Pyy finish their studies, because studying cannot be combined with motherhood. But life as homemakers does not satisfy them, either.

“If only one had been really slender, Inkeri thought – but one was as she was. They didn’t whistle as much after the slender, they were left in peace – but she wasn’t quite so fat that that was why they looked at her, and yet, she looked like a woman. You could feel when men looked at you, you thought about being a woman; otherwise one didn’t really think about it, it was as if one was naked, and suddenly had swelled up all over, making the clothes too small, as if one was only hips and breasts, and one nearly couldn’t recall one’s own name.”

Marja-Liisa Vartio: Tunteet (1962; Emotions)

Mrs Pyy (“pyy” = partridge) compares herself with “a hen who pretends to be injured”, and Inkeri remembers her old school paper “If I were a bird”. The shame over sexuality and gender keep them from realising themselves. The woman’s body and femininity is a prison. The mythical, androgynous bird-woman Alma in Hänen olivat linnut is, on the other hand, the object of dreams and fantasies of freedom and flight.

An admittedly male critic considered Tunteet to be artificial and affected. “I am probably someone who hates women writers. In spite of this I dare to propose that they hardly raise the level of Finnish literature, but exploit it.”

Suomalainen Suomi (Finnish Finland) September 1962

Kaarina Liljanto

The Power of Speech

Maila Pylkkönen (1931–1986) makes her debut in 1957 with the poetry collection Klassilliset tunteet (1957; Classical Feelings), and her poems emerge from the Finnish modernism of the 1950s, but she soon – in her next collection Arvo. Vanhaäiti puhuu runonsa (1959; Arvo. Granny Speaks her Poem) – finds her own, very particular colloquial style. When the poetry of men at the beginning of the 1960s is politicised and takes on the world and the large questions of international commitments, Maila Pylkkönen sticks to the outwardly limited lives of women, children, and the old. In her speech-like poetry, everyday life becomes a poem and is ascribed a value of its own.

As early as in her debut collection Klassilliset tunteet (1957; Classical Feelings), Maila Pylkkönen discussed how hard it was for a woman to find the voice of poetry in a male linguistic culture: “Euripides spoke as a man / […] / but with whom should I speak in accordance?” she asks herself.

Maila Pylkkönen writes about middle aged women who realise that the power over their lives has lain in the hands of others. But she also writes about women who become aware of their own strength, like granny in Arvo, when she understands that she is the only person on the entire Earth who can make pea soup the way Grandad wants it. In the collections ilmaa/kaikuu (1960; air / it echoes) and Valta (1962; The Power), the drama of the lives of women and children are shaped into long epic narratives with monologues full of phrases of speech and tangible observations from everyday life. Her pleasant, lively associative speech and the warm humour and strong affirmation of life stand apart from the ironic and elitist modernism of the time with its increasingly stronger need for the sensational. Her hallmark as a poet is lending a voice to those who live at the margins of culture, the silent and the silenced, children, old women, and the mentally ill. With these, she finds the colloquial tradition into which she writes herself. She listens for so long to her speakers that their speech becomes poetry. No object in an everyday life lived by women is so insignificant that it is unfit for a poem. The flower of the caraway plant, a grain of sand, a crystal of salt, the looks in the mirror; all become elements in Maila Pylkkönen’s almost mythical reflections.

“My way of writing is just a bad habit or a way of taking action or a kind of fear”, Maila Pylkkönen wrote in her collection Tarina tappelusta (1970; A Story of a Fight). In Virheitä (1965; Flaw) she laughs at, but also protests against, the rules of writing. Her own writings are full of ‘flaws’, she acknowledges. But it is the flaws that drive the poetry: little flaws can lead to great things. When you write poems on an electrical typewriter they are turned into prose, but not completely, since the “right margin undulates” hither and thither. The mystery that is writing, narrating, and speaking poetry does not leave Maila Pylkkönen in peace. For her poetry is everywhere, it “arises from everything”. Outer disturbances do not break down the narration, but push it forward and change it, becoming an important part of the narrating itself.

The closest circle – the family, relatives, and the husband – are an inexhaustible source for Maila Pylkkönen’s writings. Her family neither threatens nor sucks out her ego; on the contrary, they ensure a sense of self, presence, and alertness.

Tuula Hökkä

Mirkka Rekola’s Secretive Doors

Mirkka Rekola (born 1931), together with Paavo Haavikko, Pentti Holappa, and Eeva-Liisa Manner, belongs to the principals within the Finnish lyrical modernism of the 1950s. She has also been seen as the reviver of the Finnish aphorism.

Since her debut with the collection Vedessä palaa (1954; It’s Burning in the Water), with its intellectual diversity and its emotionally loaded, metaphorical lyricism, Mirkka Rekola has moved between the individually subjective, sometimes mystically irrational, and the observant mode in her writing.

By the end of the 1960s Mirkka Rekola began, in parallel with her lyrical production, to write a sort of lyrical aphorisms, later also prose poems and fables, which with their multiple layers show the writer as both an observer and an outsider.

Just as in the work of her contemporary modernist Eeva-Liisa Manner, nature with Mirkka Rekola is made aesthetic and functions through association. Nature displays the changes in the subjective sense of life and the movement between life and death.

The collection Kohtaamispaikka vuosi (1977; The Passing Place Year), and the prose poems Maailmat lumen vesistöissä (1978; The Worlds in the Snow’s Stream) complete each other. The writer feels particularly estranged and searches for confirmation of her existence through monomaniac impressions: “Have I long seen / the world, / a tourist bus in a rain wet street, / the window misted, when you look through it, / you still believe, that you are someone”.

The main motif is the open or closed door through which the writer steps into previously experienced landscapes and new worlds. Mirkka Rekola desires to be secretly integrated into the world, while she inevitably distances herself from fellowship.

Time and space are one: “the year is a place, a city, twelve doors”, she says in Maailmat lumen vesistöissä. Like the seasons, the poetic speaker moves through an eternal cycle and meets with unexplained obstacles: “The are places closed, yet, yet there is an obstacle, / a large bar a small bar / cat cat cherub. / Where am I going, / at this time the doors / are still closed. / I keep vigil, / I must keep vigil / over that which keeps vigil over me. / It is open in all directions. / That is how the wanderer must be. / Disappear through the door. Nobody notices”.

The condensed formulations and the sensual formation of the details of the moment are characteristic for Mirkka Rekola’s poetry. She achieves a paradoxical effect – on the one hand a splintering and a drifting away, on the other hand an intense presence.

In the collection Kuutamourakka (1981; Working Under the Table), the eleventh since her debut in the 1950s, the writer similarly attempts to open closed doors and establish contact with her surroundings through dreams and memories: “What a long way to this door, / and now someone, who reminds me / of my youth, the ineradicable”.

But the author still feels like an outsider, she continually walks in circles, moves from the innermost self to the world. Memory is just as real as outer existence. The you of the poems, the he, she, they, that, and the child, the world the writer tries to reach: “My broadening / the sunset’s / evening brown surface, / I looked at you, at people / against each other, past each other”.

The harmonic form and the stylistic stringency creates an antithesis of intensification and rupture, oscillates in an ever-present poetic dynamic. In her later production she is heading for a much more ‘silent’, sparser language. That which is difficult to understand and the theoretical, formally flexible also shows in her aphorisms. Tuoreessa muistissa keuät (1987; Spring in Recent Memory) gathers the aphorisms from the aphoristic collections Muistikirja (1969; Memory Book), Maailmat lumen vesistöissä (1978; The Worlds in the Snow’s Stream), Silmänkantama (1984; As far as the Eye Can See), and the title collection.

But Mirkka Rekola’s intellectual, linguistically terse aphoristic poems, a sort of modified aphorisms, also enter the natural cycle, while still describing an inner landscape. The poetic speaker expresses her wish to live in her vision and still turn grey at the same rate as the wood in which she wanders. The poetic speaker is continually involved in a strife between the self and the world, the common and the private, the metaphorical language and the aphoristic paradox.

In the 1960s Finnish Leena Helka (born 1924) published four collections of poetry in Swedish. She was praised by the Swedish critics for her linguistic inventiveness and vitality, and for playing with language in a way that also contained elements of melancholy and depth of gravity. “If you have death for your tutor / one has to learn to live intensively”, it says in the collection Sju systrar (1962; Seven Sisters). A year later, in the third collection Halva djurriket (1963; Half the Animal Kingdom), the introductory poem to the suite “Summer Nights” is as follows:

Earth.

Soil in the hand.

Stepmother’s hand wishes me

well.

I

– and a dead bird –

before I opened my eyes.

Earth reaches for water

and drinks.

The grass grows, the flowers break

open.

The defenceless questions open again and again.

Elisabeth Nordgren

Translated by Marthe Seiden