“Tell me, Ms Penwoman,” asks a smug gentleman in an attempt to understand the young journalist’s shocking radicalism, “wouldn’t you choose to be a man if it were up to you?” “Not at all,” she answers, “how about you?”

The exchange appears in a novel by Elin Wägner (1882-1949) entitled Pennskaftet (1910; Eng. tr. Penwoman). As opposed to the smug gentleman, the reader cannot help admiring the feminine self-assurance that the novel exudes. Such confidence is rooted in the financial independence, professional pride, and boundless optimism that a new generation of women experienced on the threshold of acquiring full civil rights. Norrtullsligan (1908; The Nortull Gang) had already portrayed the “self-supporting educated women” of Wägner’s time, but her inside view of the National Association for Women’s Franchise in Pennskaftet made a unique contribution to twentieth century Nordic literature. The suffragettes in the novel exploit every means at their command to transform patriarchal society – office routines, newspaper sales, lecture tours, and election campaigns.

While the term penwoman immediately caught on as an epithet for female journalists in Sweden, the character herself harboured ambitions beyond her profession. She explains to her friend Cecilia that “I write to live and I live to grow wise and perhaps write a book one day.” It is hard not to associate those words with the novel itself. Not only that, but Wägner had taken it upon herself to revise a book by no less a luminary than August Strindberg. Pennskaftet can be interpreted as retort to his Taklagsöl (1907; Eng. tr. The Roofing Ceremony).

The women in Pennskaftet who celebrate their election victory amongst the crowd gathered at Gustaf Adolf Square represent an antithesis to the suffocating, self-enclosed space of Taklagsöl. Strindberg’s patriarchal worldview is based on insecurity and fear that stifle the life force, Wägner seems to be saying; what a difference it would make if men had the courage to acknowledge women as their equals. Wägner’s speech before the first course at the Fogelstad School for Women Citizens in 1922 argued that women had to emancipate themselves so that they could “find a form of their own.”The provocative rewrite of Strindberg’s book was Wägner’s first serious attempt to break with established literary structures and devise her own alternative.

The Journalist, the Writer, and the War

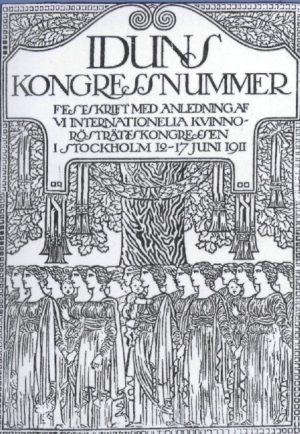

The author of Pennskaftet was herself a journalist. Having started off at Helsingborgsposten, she obtained a job at Idun (a women’s weekly) in 1907. She also contributed regularly to Dagens Nyheter in Stockholm. She pursued her journalism career and wrote fiction side by side for a number of years. Due primarily to her pacifist activities, she left Idun in 1916.

Wägner drew inspiration for her pacifist feminism from Olive Schreiner, Rosa Mayreder, and other writers. She fondly cited the assertion of Hungarian journalist Rosika Schwimmer, whom she met at the 1915 International Congress of Women in The Hague, that the war confirmed “the bankruptcy of the manmade world.”

It is no accident that the limits of journalism are so finely delineated in Släkten Jerneploogs framgång (1916; The Success of the Jerneploog Family); the war had lent a special significance to literature by women. Set in the town of Gustavsfors, the novel features the editor-in-chief of a liberal-conservative newspaper who is not only beholden to his shareholders, but manipulated by the powers-that-be. Meanwhile, the bishop’s pacifism remains hidden. The author herself is bound by no such constraints; she spends more than three hundred pages analysing both the situation in Gustavsfors and the devastation of the war.

The novel joins forces with the individual struggle for participatory democracy, clearly a reflection of Wägner’s commitment to the feminist cause. The quest for “a form of their own” creates striking and new symbolic patterns. The plot revolves around Ingar Gunarson, who assumes the proportions of the Great Mother while representing a counterpoint to Ellen Key’s conviction that women can transform society through their maternal role. As it turns out, the maternal strength is no match for a world war. Ingar’s son Allan dies in a vivid illustration of the patriarchy’s power. Åsa-Hanna (1918) is about a young woman from the province of Småland who is forced to marry into the notorious Mellangård family and must hold her tongue about their crimes year in and year out. Once again Wägner’s mystical tendencies appear, and the cogency of the novel stems largely from her invocation of the Bible to zero in on the deadly institutions and ideals of patriarchal society.

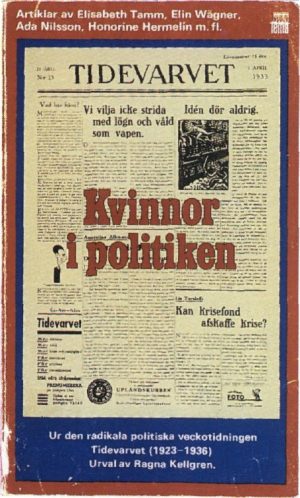

Wägner was among the co-founders of Tidevarvet, the political weekly of the Association of Liberal Women, in 1923. According to the mission statement in the first issue, the magazine would be a “forum, an arena in which men and women can work side by side to forge a broad-minded vision and find ways of implementing it in legislation and community life.”

She was editor-in-chief of Tidevarvet for three years in the 1920s and wrote more than six hundred articles – mostly about peace issues and international politics – during the thirteen years of its existence. Tidevarvet also serialised a number of her short stories and novels.

The Women´ s College for Civic Training at Fogelstad, which began offering courses in earnest as of 1925, provided Wägner with an inspirational venue. As one of the founders, Wägner lectured there on a regular basis. While her radical feminism appears to have been fairly unique in the group, the importance of the affiliation became obvious in 1940 when she presented Fred med jorden (Peace with the Earth) – her conservation programme – in collaboration with Elisabeth Tamm, an experienced farmer and the owner of the estate.

The Present and the Living Past

The works that Wägner published immediately after Åsa-Hanna, represented a watershed among the twenty novels, a handful of short story collections, and many radio plays that comprised her prodigious output. Her novels of the 1920s and 1930s articulated a clear-sighted, persuasive plea against the destructiveness of the patriarchy and in favour of fruitful collaboration between the sexes. While not advocating the restoration of matriarchal society, she thought it was vital to raise awareness about the patriarchal system and the fact that it was not the natural state of affairs. The symbolic and mystical dimensions of her contemporary narratives open the door to a living past. The past serves as a critique of the present, suggesting that improvement and redress are still possible.

Dialogen fortsätter (1932; The Dialogue Continues) deals with abortion legislation, the population crisis, defence issues, pacifism, and many other issues of the day. The unifying symbol of the novel is the Gas Mask Madonna, the 1930s version of the Great Mother, who holds her dead son in her arms, rips off her mask, and turns her dying face to the toxic sky in the knowledge that it is all too late.

The plot can be interpreted as a dramatisation of Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion (1903)and Themis (1912), British classical scholar Jane Ellen Harrison’s celebrated works about Greek mythology and ritual. The books – which Wägner read along with her friend Emilia Fogelklou, a theologian and author – trace a line of development from the underworld gods of fertility to the remote, intellectualised Olympian gods, demonstrating the steady distortion of feminine values in the process.

Wägner was increasingly interested in the works of Sigmund Freud, as well as The Golden Bough (1890-1915) by Sir James George Frazer. Both men had demonstrated the universal reach of myth and archetype.

Märta, a journalist, finds herself impossibly wedged between the Great Mother (Stina Ek, the protagonist) and Zeus (Stina’s ex-husband, the vice-president of a bank and a member of Parliament). Feeling as though she is ensnared in the jaws of modern patriarchy, she assumes a male pseudonym to make her voice heard. With her big, round glasses and her haunts under Stockholm’s roofs, Märta is a kind of Pallas Athena. Meanwhile, Stina demands “a world into which women will dare to bring children”, and her mystical proportions point to the possible origins of such a revolution.

The End and the Beginning

Wägner designed her novels Genomskådad (1937; Seen Through) and Hemlighetsfull (1938; Secretive) as “a woman’s autobiography”, thereby throwing down a feminist gauntlet before the genre that dominated Swedish fiction of the 1930s: the autobiographical coming-of-age novel.

Both books centre on the interplay between the three chronological sequences in Agnes’s life. Out of the narrative present, tinged by feminist awareness, emerges a past in which she is inextricably bound to a patriarchal system. The third sequence, half buried under the other two, is a mystical paradigm that serves as an antidote to patriarchal authority. Perhaps because the trilogy was never completed, the fairy tale lacks a happy ending.

Agnes marries her guardian, living out – if Freud is to be believed – the young girl’s fantasies about her father. The point is that the young man whom Freud would posit as the future object of her affection turns out to suffer from typical Freudian neuroses: passive and self-absorbed, he is incapable of reciprocating her love.

The novel exploits all of Freud’s theories, but is critical as well. The Swiss sanatorium in which Agnes’s lover undergoes psychoanalysis is described as a patriarchal stronghold. Most of the patients are wounded soldiers, who are patched up just well enough go back out and serve as cannon fodder. Agnes suffers profuse bleeding, which symbolises both her protest against the established order and her creativity. The incident is the prelude to her resurrection, and she creates a new life for herself as a writer in war-torn Europe, drawing support from an international sisterhood. She begins to write a story, intended for her younger sister, about her own life. Presented as a kind of fairy tale, the story uses myths and symbols to sketch the outlines of an alternative world.

Väckarklocka (1941; Alarm Clock) was written during another world war, and is one of the best Swedish examples of the way that feminism has inspired artists to question and transcend established genres.

Väckarklocka unabashedly throws Swedish and foreign culture, present and past, myth and scientific research into the mix. Its bold style makes generous use of italicisation and lists of essential points, dialogues with sceptical readers, and quotes that range from political oratory to poetry – not to mention personal sketches and anecdotes.

Critics unanimously thought that the form of Väckarklocka was flawed. According to the biography of Wägner published by Ulla Isaksson and Erik Hjalmar Linder in 1980, she treated her “refractory material on the basis of a precipitate, hit-or-miss principle.” But the book is actually a meticulously constructed overview of an ancient matriarchal era and the transition to patriarchy, followed by a detailed analysis of the modern feminist movement and its failures. While stressing the significance of Key’s “struggle […] for the prerogatives of female personality within the emotional sphere”, Wägner argues that her demand that women perfect human love by rejecting the working world created by men is unreasonable. From Wägner’s point of view, Key was fighting a losing battle because she ignored the history and scope of patriarchal society.

Translated by Ken Schubert