Carola Hansson’s (born 1942) oeuvre is at the centre of the aesthetic turn of the tide and epistemological turbulence of the 1980s, but her novels still deviate from the main literary path. The books, like so much of the decade’s prose, deal with an identity in dissolution, a lost language, and the evasive nature of memory. But there is a very special tone to her writings, something breathless, translucent, and almost ethereal, that makes them stand out.

Stilleben i vitt (1985; Still Life in White) is Carola Hansson’s second novel. But the title characterises her entire oeuvre. Her texts are, like the painting at the centre of this novel, painted white on white, shimmering with light, and with a few daubs of colour laid out in a very precise, imaginative, and inciting pattern. Whiteness is Carola Hansson’s leading aesthetic device, and it is also her most highly charged metaphor. It carries her systematically-driven criticism of rationalism. The white light is a killer in Carola Hansson’s novels. But it also, paradoxically, contains the strong, almost excessively boundary-breaking and life-affirming tone of longing found in her works.

Carola Hansson belongs to the generation born in the 1940s, and her debut novel, Det drömda barnet (1983; The Dreamed Child), initially behaves like a continuation of the identity and conquest project of the women writers of the 1970s. The novel’s Gerda fights her mother and seeks a female identity, as if she had been the protagonist of a woman’s novel of the previous decade. But Gerda never finds a whole identity, nor does any other character in Carola Hansson’s oeuvre, and throughout the 1980s, Hansson very consistently writes herself out of the 1970s project.

Her imagery is modernist and elaborate, with tried and trusted nature- and, above all, bird-metaphors. Her colour symbolism employs the traditional whites, blues, reds, and blacks. But while she strikes the modernist sounding box and allows its resonances to reverberate, she dissolves the traditional translations in which blue represents longing, red is love, white innocence, and so on. The established signs lose, rather than gain, meaning in her narratives. Identities are emptied, concepts dissolved. What is apparently solid evaporates, and knowledge of reality becomes far more inaccessible. The main point in Carola Hansson’s novels, in spite of their long passages of vibrant presence, seems to be the absent, the lost, and the unobtainable. “The better I knew Karel’s mother tongue, the more words and expressions I mastered, the more alien they seemed to me,” the main character thinks in Resan till det blå huset (1991; Journey to the Blue House); “yes, paradoxically, the closer I grew to the meaning of the words, the more distant and inaccessible did they seem to me.”

Carola Hansson’s narratives turn on what has not been said: words that are not spoken, images that dissolve, people who died or disappeared. The protagonists nearly always have an absent alter ego, a point of fascination not just for the protagonist but for the entire narrative. In Resan till det blå huset and in Pojken från Jerusalem (1987; The Boy from Jerusalem), there is a dead younger sister. In Andrej (1994; Andrej), a younger brother is long deceased. But rather than the specific longing for those who are gone, the theme of the narratives is the void they have come to be in the protagonists’ inner selves.

When Henning, the protagonist of Pojken från Jerusalem, at the start of the novel finally reaches his childhood home, he finds the house empty. There is an explanation. The family has gone into the countryside. But metaphorically, it also says something about Henning. The house, the symbol of the self in traditional psychoanalytical theory, is empty, and over the course of the narrative, Henning’s dreams of rediscovering its contents and significance are emptied, too.

In Pojken från Jerusalem, it is the absence in Henning’s life that charges it with meaning, just like emptiness charges Carola Hansson’s narrative. The four years he does not remember, the childhood that he cannot reach except in fragments. The absent memories, the absence of emotion, meaning, and identity, are what drive him. The most important people in Henning’s life are also absent: the sister Sonja, who became ill and died when he was little, and the brother Gustav, who left for Palestine while Henning was at the mental institution and is the novel’s title character, the boy from Jerusalem, who refuses to be photographed and whom he only meets in Gustav’s letters and stories.

Henning has just absconded from the city’s hospital for the mentally ill. He seeks himself and his family, and when they are not to be found in the house in the city centre he goes into the countryside to look for them at the family cottage. But that, too, is void of people when he arrives, though rather full of loss and fragments of dead memories. The father’s map drawings of the perfect white city – always a work in progress – are on the desk, the photograph of his dead younger sister is there, the collection of emptied bird’s eggs is in his abandoned boy’s room. During the year of the narrative, the house is peopled again, but those most loved – those who are most present in the narrative and in Henning’s inner self – the dead sister, Sonja, and the brother who left, Gustav, remain missing. And Carola Hansson lets Henning journey through his landscape, from the city centre to the periphery of the countryside, between the two houses and their interiors, while they are abandoned and are finally emptied of belongings. In the apocalyptic final scene of the novel everything is forfeited, and Henning carries his dead drunk father out into an icy white landscape. He has burned the drawings for the hygienic city, where light was to stream through the straight streets and the sunshine was to glisten on pure white walls with large windows. And before Henning himself walks into the glittering and sparkling whiteness that is death, he buries his father in a snow-cave, leaving him to freeze to death at the edge of the ice-covered lake.

“[…] her tale was very long and full of details and things that at first did not seem connected to the story, but which turned out to be more important than anything else,” Henning thinks in Pojken från Jerusalem about one of the stories that his dead sister Sonja used to tell.

Just as in Sonja’s tales, the apparently irrelevant details are extremely important in Carola Hansson’s texts. Sonja herself is such a detail, where she sits in the darkest corner of the kitchen or in a bed with her unicorn. Half invisible, both in the narrative and in the text, she and her fairy-tale animal indicate an alternative history. Like the ancient tale about the virgin and the unicorn, in which the virgin is the only one who can capture the shy, white animal, calm him, and deliver him, Sonja is the image of the repressed gospel of love. It exists, the novel claims, even if it in the modern context is placed in the kitchen, under the work-table, or in the sickbed.

Carola Hansson consciously seeks her way through to the characteristics of existence. Her investigations are about the limitations of the text, of identity, and of knowledge. And her novels, which almost seem to grow out of each other from an inner necessity, successively lose their chronological structure and take on the shape of triptychs, circular compositions, or quite simply loose chunks of associative memory fragments.

“We may not even be moving forwards,” Viktor thinks in De två trädgårdarna (1989; The Two Gardens), “we may be moving in circles, perhaps we distance ourselves from the goal we set.” Viktor has left his family to break new ground on an inherited farm far away in Central America, but his journey into the world does not bring him to the alluring goal. Everything that appeared worth striving for dissolves as he approaches it. The orchard grows over, the fruits rot. The white island that tempted him in the ocean turns out to be full of migrating birds when he finally gets to it. Expansion is impossible, and so is reconstruction. Not even memories are accessible. They are, he says somewhere else, “like stars, extinct heavenly bodies, still existing through their remnant light, secretive signs, at once filled with meaning and totally without significance, a final proof of the meaninglessness of existence.”

The focus of Carola Hansson’s novels is the modernist anti-hero: a homeless, alienated human being seeking his identity without ever finding it. Already in her debut novel, Det drömda barnet, she strikes the sounding-board of grief and inability, continued seeking and incessant longing, that resounds throughout her oeuvre. Gerda in Det drömda barnet is haunted by powerlessness and feelings of guilt, just like Paula in Stilleben i vitt. Henning in Pojken från Jerusalem is eaten up by an anxiety so strong that he enters a state of psychosis. Viktor in De två trädgårdarna and Hanna in Resan till det blå huset abandon everything in order to seek out an answer to the pain and loss they live with, far away from those who are actually important to them. Like Andrej in the novel bearing his name, they live in mental confinement within the memories of those who once renounced them.

The dreamed child of the title of Carola Hansson’s debut novel hovers like an insignia over her entire oeuvre. Her novels are filled with children, most of them absent. At a very concrete level they are children who have died: a sibling, a relative, or a play fellow who disappeared far too early and left the survivor with a never-resolved sense of loss. Often they represent the unseen, the unloved, and the disavowed people who have been cast out and banished to the margins of society. One of the least of these who are members of my family, to use a term that springs to mind, even if Carola Hansson herself never uses Christian terminology. There is strong pathos in her novels, even if they never address any specific social issue. On a more metaphorical, and just as important, level there is a very obvious theme – the dead child that Carola Hansson’s protagonists carry within. The death eating away at every human being every day, but even more the child they once were themselves, whom they allowed to die, or outright killed.

The Live Corpse (1900) is the drama by Leo Tolstoy that Carola Hansson built her novel Andrej around. Hansson’s book is about one of Tolstoy’s sons, and the novel is filled with dead children. The protagonist Andrej seems surrounded by dead and dying children. Several of his siblings die in infancy. And clearest to him stands the dead brother Aljosja. Andrej keeps seeing him come running through crowds with his yellow scarf floating behind him. Foetuses die in the wombs of his sisters, who must time and again give birth to stillborn children. Life, love dies around and inside him. There is an ongoing war in Manchuria. The corpses are piling up, but worst of all is the death Andrej’s father has written for him in his play, which is about two brothers: one good, the other evil. Andrej reads the evil brother as a portrait of himself, as a father’s judgement.

But while he does all he can to avoid it, it is as though he cannot escape his father’s text. He is imprisoned in it and is slowly transformed into the living corpse that his father has created for him in his writing, and that only death can deliver him from. Many threads from Carola Hansson’s oeuvre are woven together in Andrej. Here, the conflict between parents and children, which has been played out in all her previous novels, falls in with her consistent criticism of language. Here, every optimistic liberation theology, from Tolstoy’s teachings of love to socialist revolutionary romance and middle-class belief in progress, definitively get swept out the door. The unity of grief that has surged through her novels has been caught in what resembles a case study of melancholy, and the elaborate aesthetics of whiteness has been taken to extremes.

Mementoes and photographs are a theme throughout Carola Hansson’s writings. “Why precisely these three images?” Andrej thinks in the novel that bears his name. “Why, it went through his head, had his mother of all the hundreds, probably thousands of photos she had taken, selected just these three – these being practically the ones where no people are around.” The photographs his mother has sent him are just as inscrutable as his own remembered images. Mysterious and evasive, just like the photographs left by the brother Frans when he fled to the United States in Resan till det blå huset. Empty, just like the images Gustav sends back from Jerusalem when the family asks for a picture of him in Pojken från Jerusalem.

Lisbeth Larsson

She/I will be the Princess without Blood or Weakness

As early as in her debut children’s book, De vita björnarna, (1969; The White Bears), Åsa Nelvin (1951–1981) depicts the conflict between the self and the world that will underpin her entire body of works. The little girl of the book, Kerstin, goes through an initiation rite that, in the novels Tillflyktens hus eller En f.d. inneboendes erinran (1975; The House of Refuge; or. The Memories of A Former Lodger) and Kvinnan som lekte med dockor (1977; The Woman who Played with Dolls), assumes the characteristics of an outright passage through hell and degradation.

In Tillflyktens hus, Åsa Nelvin points her critical pen at the traditional gender roles that were the focus of the women’s movement in the 1970s, and writes herself into a woman’s literary tradition. In this sense, she writes ‘with’ her time. But her criticism is also aimed at the, for the women’s movement, much more positively loaded concept of ‘identity’, which means that she also writes ‘against’ her time. The question Åsa Nelvin forces on the reader is whether a female identity actually exists, or whether such a supposition necessarily must be placed in the sphere of utopia, the realm of things not yet in existence?

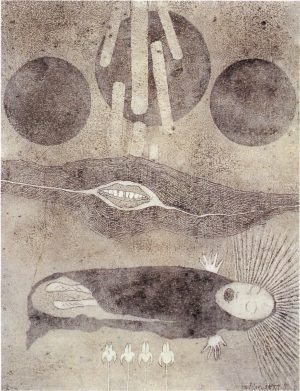

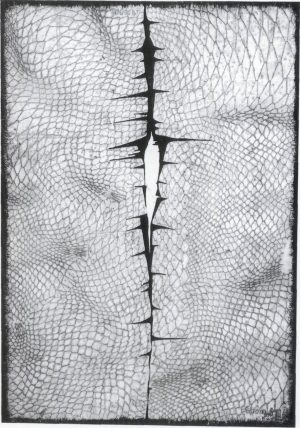

Bankier, Channa (born 1947): Drawing. In: Channa Bankier: Hemifrån. Bok med bilder, Bildförlaget Öppna Ögon, Stockholm 1979

In Tillflyktens hus, Åsa Nelvin orchestrates an intricate meta-fiction. In the introduction we are told that ‘N’ reads this story, about ‘N’, presumably written by herself and identical with the book that we are about to read, out loud. The reader is engaged by ‘N’s direct address; the first-person narrator of the text is multiplied, and one must ask who the book is actually about: the woman ‘N’, who reads out loud a manuscript that she finds in an apartment that is about to be demolished, or someone else, also called ‘N’, who left the manuscript behind? A third option is to disregard the narrative frame and completely read thematically the raw, claustrophobic story about ‘N’, to simply read the book like a traditional story in the realistic vein, about a compelling female fate. A fourth alternative is to form an autobiographical link to the author, since the protagonist is called both ‘N’ (Nelvin) and ‘I’.

The woman ‘N’ in Tillflyktens hus takes the traditional woman’s role into absurdity. She adopts different poses: the mistress, the masochistic victim, the good family girl – all summarised tragicomically in one passage in which ‘N’ buys a Barbie doll and tries to transfer her ego to the doll.

In reality, Åsa Nelvin plays on the reader’s desire to psychologise or read the book autobiographically. What Åsa Nelvin does is different from telling her life’s story or filling an alienated femininity with a positively loaded identity.

A convention of fairy-tales that also applies when reading novels is the desire to know ‘how it ends’ or ‘what happens next’. Åsa Nelvin teases this desire: “Right. A possible introduction: What happened next? (I am very interested in phrases, I should add. For me every hackneyed phrase is divine. I consider them the martyrs of language who can never be dirtied, however vilely they are belted out.) […] Let us play the game, ‘What happened next?’”

Åsa Nelvin’s works are criss-crossed with clichés, which are a means of underscoring the conventional character of writing identity, and the fact that an author has a lot of phrases at her command, which she may use to impress a sense of authenticity or illusion upon the reader.

The hackneyed and ironic traits in Tillflyktens hus thus multiply and destabilise the ‘I’ of the text. But they also draw the reader’s attention to the fact that the depiction of this dissolved female ‘identity’ is a means for Åsa Nelvin to discuss women’s relations to language, creativity, and a possible but not yet realisable new femininity. ‘N’ wants to be a third thing, neither man nor woman, but a ‘She/I’ or “the princess without blood or weakness” who meets the world as a new person. This gender-transgressing person can only gain new content if we imagine something that does not exist yet. To get there, ‘N’ must undergo a painful transformation, during which her personality traits and gender characteristics are shed and destroyed.

Åsa Nelvin treats not just the traditional women’s roles with irony, but also the time’s political engagement. In Tillflyktens hus, the protagonist ‘N’ plays chess with her boyfriend Mårtensson, who is a Marxist: “‘chess contains all human need of thought,’ Mårtensson says and strokes his red beard. ‘It is the principle of life. Every human who sympathises with Marx must train and deepen his mental ability through chess, which is where he learns to strategically combat the bourgeoisie.’” To ‘N’, “chess is a party game like any other, as uninteresting as canasta or ludo, and just as filled with turn-of-the-century nostalgia as a croquet ball rolling into the sunset. But for Mårtensson it is the Core of Life.”

The road to the loss of identity in Tillflyktens hus is a passage through hell, and in the blurb, the author calls it a schizophrenic process. When ‘N’ has hatefully settled with the traditional female roles, there remains a step into the darkest corners of the self. ‘N’ escapes to a boarded-up house that takes on several meanings: the house is the self, it is the body, and it can also be a hospital for the mentally ill.

In the house ‘N’ is confronted with herself in a nightmarish way, until she finally gets out, or ‘writes herself out’. At nights she finds her way along empty streets to a condemned house. There she finds a badly mauled manuscript, presumably her own narrative about herself, that she begins to read aloud to us. Thus, the circular narrative frame that opened the book is concluded.

But the price that ‘N’ pays for her creativity is high. It takes the pain of being an outsider and a descent into the dark and the difficult. ‘N’ disavows all relations with fellow human beings. She lives a schizophrenic life, balancing on the edge of suicide, and swings between aggressive arrogance and degradation. Suicide is the consequence if the renunciation of identity is carried to extremes.

By the end of the book, ‘N’ decides to survive. When she leaves the house and we leave Nelvin’s text, no happy ending or any therapeutic realisation is noticeable, despite the averted suicide. What may be happening is an opening towards something unknown, which might be the utopian potential of a dissolved identity: the third gender, or the new human.

The strength of the depiction of the schizophrenic hell that ‘N’ enters in Tillflyktens hus lies in the realistic touch. The psychologist and literary historian Marianne Hörnström has expressed it as follows: “dreams and mad visions do not have ‘dreamily’ blurred outlines. Kafka knows this. Magritte knows it. Åsa Nelvin, too, knows that the lucidity is as clear as glass. N is the heroine of Tillflyktens hus. But her perception of reality is not changed when she leaves the ‘real’ world behind and steps into the world of dreams, the subconscious, and madness. Both worlds are described by N with the same level of concreteness, and the one world is just as ‘real’ as the other.””Att själva det oförstådda är min identitet” (That the uncomprehended itself is my identity), in Marianne Hörnström, Flyktlinjer. Aningar kring språket och kvinnan (1994; Lines of Escape. Intimations about Language and Woman)

The sarcastic and high-strung tone is somewhat lowered in the novel Kvinnan som lekte med dockor. In the blurb Åsa Nelvin explains that she wishes to depict a woman’s fight to reach a truer women’s role. The motto of the book is Simone de Beauvoir’s “Real sexual maturity only comes to the woman who accepts being flesh for better for worse.” But the novel transcends the motto, and must be read ironically. Again, Åsa Nelvin tells the story of a woman who refuses to adapt to the traditional woman’s life that is on offer and who strives to be completely free. This time through a masochistic love relationship that demands the obliteration of mutual giving and taking.

In Åsa Nelvin’s last book, the collection of poems Gattet. Sånger från barnasinnet (1981; The Guts. Song’s from a Child’s Mind), the sarcastic and ironic address to the reader is transformed into a serene and humble “follow me”. Åsa Nelvin takes the reader by the hand through her childhood. The persons are depicted with loving devotion. How could the result be any different in the close-minded working class neighbourhood? The grown-ups who shaped the little girl were themselves marked by a repressive environment.

There is an intense sensuality in the poems – smells, specific moments mentioned in detail – just as there is an eye for the loving relationship in these people’s wordlessness. Inability to express oneself is not always the same as pent-up silence. But the poems form at last, in spite of the new and insightful humility, into a closing of the books on a time of alienation. The little girl in the working-class neighbourhood grew too swiftly, designed on an unknown star, basically in exile and homeless. In the end, she packs her bags and advises the reader: “do not follow me any longer. There is no need. I am on my way to you.”

Cristine Sarrimo

Translated by Marthe Seiden