Katri Vala (1901-1944) articulated a new kind of vitalism in Kaukainen puutarha (1924; The Faraway Garden), her first book of poetry. The symbol of the life force is the soil, whose power of renewal is inexhaustible, as in “Kukkiva maa” (Blooming Earth):

The earth is frothy from the bluish-red clusters

of the lilacs,

the bird cherry’s white flowery foam

the red swarms of the German catchfly.

Blossoming in blue, yellow, and white,

the meadows billow like furious seas.

And the smell.

More fragrant than holy incense.

Hot and quivering – intoxicating with madness.

Heathen aroma of the earth’s flesh.

Live, live, live.

Live the soaring moment without hesitation.

In magnificent bloom with wide-open petals

overcome by giddiness, inebriated by the sun, live.

The most innovative feature of Vala’s poetry is its visual lucidity. Another characteristic is its free verse, which took hold in Finland partly due to her. During the 1920s, she was the central figure of a literary group called the Torchbearers, which represented the first generation of authors after Finland obtained its independence. Their goal was to overturn existing literary conventions. Vala’s imagery also reflects the use of primitive and exotic elements by early twentieth century modernists. In primitive cultures they found the original life force that art needed for renewal, and they countered the prevailing culture with exoticism.

Kaukainen puutarha links such images to the love motif. The moon shines as a powerful feminine symbol in many of the love poems, no longer associated with winter and death as at the beginning of the book. The sun, a staple of patriarchal imagery, loses its privileged position.

Sininen ovi (1926; The Blue Door) places love ecstasy at centre stage. The erotic milieu is often a mysterious cabin or a “hut in the wilderness”. The blue door is “an opening to everything / that does not exist, / that we only dream of.” Love is portrayed openly and unabashedly, and sexuality is decoupled from sinfulness.

Death is a hallmark of Vala’s poetry from the very beginning, but takes the helm in Maan laiturilla (1930; On the Pier of the Earth). It has now risen to the same status as life. The narrator in “Onnellinen” (Happy) stands between “two wondrous states of being”, both of which are “marvellously seductive / as only adventure and the unknown can be”. Death is a more genuine option than before, no longer a source of contrived horror.

After developing tuberculosis, Vala was increasingly on intimate terms with death. Living in quarantine added insult to injury. “Autio kaupunki” (Desert City) reflects the narrator’s feelings of solitude and isolation:

“My heart is a city, / that has been abandoned by its inhabitants. / […] / the sun shines fearfully on objects, / that nobody dares to touch.”

Maan laiturilla.

Paluu (1934; The Return) makes it clear that Vala had re-established her connection with people. Now linked to collective anxiety, individual suffering also assumes new proportions. “Pajupilli” (The Willow Flute), the first poem, has been interpreted as a lyrical version of Karin Boye’s article “Tendens och verkan” (Tendency and Effect). The narrator does not want to be a standard-bearer of social struggle, even though she sees adversity all around her. She is only a “willow tree from which the spirit of rebellion breaks off a simple flute / to play a melody / with storm, anxiety, love, / and a little aurora in it.” An artist best serves the common cause by keeping people’s spirits high.

Paluu introduces a whole new series of themes revolving around motherhood. The focus shifts from romantic love to the intense relationship between a woman and her child. Mother and child create a magic circle that shuts men out. However, the notion of maternal love expands to take in social responsibility as well.

“Äidit” (Mothers) in Pesäpuu palaa (1942; The Warden Tree Is on Fire), Vala’s last collection, laments: “Painful to be a mother / in this world. / You have been horribly wounded, dear life, when mothers say / better that the child should die.” The poem ends with the hope of a better tomorrow for both children and the entire world: “Perhaps they will come? / redeem? /the strong, the pure, the unafraid!”

Vala also wrote columns of social commentary. Among her concerns was the establishment of offices of sex education. The conservative press accused her of indecency. She inflamed moralists by defending Agnes von Krusenstjerna – some of whose works she had translated, along with those of Karin Boye and Moa Martinson.

For a Better World and against War and Fascism

Spending time in prison was a crucial event in the life of Elvi Sinervo (1912-1986), who started off with a book of short stories entitled Runo Söörnäisistä (1937; A Poem from Sörnäs). The most important prose author in the left-wing Kiila (Wedge) group, she was sentenced in 1941 to four years at a house of correction for participating in illegal political activities.

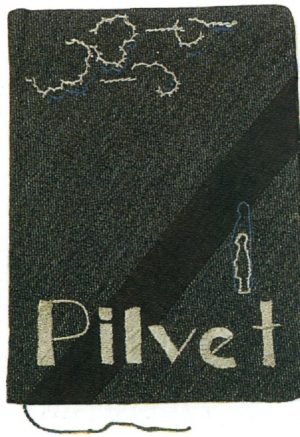

While in prison, she wrote poems that were published in Pilvet (1944; Clouds). The title poem tells of her arrival at the facility: “I lived, loved, / and when I was thirty / I put on a prison uniform”. She refused to confess to any offence, unless it was the crime of living and loving. As a political prisoner, she fell into a different category than those who were there due to their sexual orientation, “making buttercup wreaths / for the women they love / at the foot of the white wall”. The loss of liberty is a harrowing experience, even for someone who knows that she has done no wrong.

Tears are an ineffective weapon in the battle against folly. Of more use are the “grenades” that fly into the faces of the villains in “Nauru” (“Laughter”): “Fly, my laughter, / explode, red laughter.”

An inmate could not look out across the prison yard. She could see only the clouds, the symbol of longing in Sinervo’s later work, through her cell window. Dreams provided an outlet for anxiety and highlighted the similarities rather than the differences among the prisoners. The woman inside the ‘political animal’ yearned for her children and her beloved, as in “Yön tullessa” (At Nightfall) from Pilvet.

Sleep comes to me through locked doors

in the harbour of a soft, dark bird.

I crawl as I used to, trembling with joy,

into your beloved arms.While Vala was still incarcerated, the political prisoners brought out a ‘first edition’ of her poetry with a cover cut out of a prison uniform. The poems make it clear just how important solidarity was to them. Although prohibited from talking to each other, they communicated by rapping on the walls. Looks and gestures were vital as well. “Rangaistussellissä” (Punitive Confinement) describes the role of wordless communication:

Your flower will soon wilt, sister.

The darkness is heavy,

Its radiance has withered in my hands.

But a gift I received without asking, a smile,

still glows on the drooping petals.

Anyone suspected of being an informer was ostracised. The novel Toveri, älä peta (1947; Comrade, Don’t Betray Me) chronicles the cruelty of such punishment. Marja, the protagonist, has given away a fellow inmate by mistake. She is excluded by the others and later looks back on her reaction:

“When I was left all alone and nobody would speak to me, I started talking to myself. Mostly I muttered under my breath, but occasionally I noticed that I had raised my voice. I talked to the inmates on the other side of the wall, explained everything, and assured them that they would understand once they knew the whole truth. I did not exist for them; no longer did I even look their way. If somebody stood in front of me in line, she would stare right through me when we did an about-turn unless I remembered to turn around fast enough.”

Viljami Vaihdokas (1946; Viljami the Changeling), Sinervo’s most significant achievement, illustrates the importance of belonging to a collective.

The title character is a boy with a club foot who dies after having been abused in prison. He bears some resemblance to Joan of Arc and other freedom fighters who have been sustained by the faith that their ideas would one day triumph. He has felt like an outsider all his life. Not until he becomes a left-wing activist does he find a sense of community.

“Viljami the Changeling sat in the hall with hundreds of others […]. His face had merged with theirs. He no longer possessed a body of his own, no deformed foot that had set him apart and caused him so much anguish. There was no suffering, no joy, no life that belonged exclusively to him, either in the past or in the future.”

The utopia that Sinervo chronicles in this novel is a socialist state “on the other side of the dark forest”.

The themes of the book place it squarely in the anti-Fascist literary tradition. Sinervo saw the war between Finland and the Soviet Union as part of a worldwide struggle. Thus, she equated the radical left-wing underground in Finland with the resistance movement on the Continent.

Ulla-Maija Juutila