“Do I have the courage? Dare I write something from my own point of view without worrying about what my family or other people will think? Would I have the strength to pour my very being into a book like I have dreamed about for so many years?”

Agnes von Krusenstjerna (1894-1940), a scion of the nobility, was twenty-five years old when she posed these anxious questions to her diary. The book she had in mind was the trilogy that appeared in 1922-1926 and centred on a girl named Tony Hastfehr. The first volume was entitled Tony växer upp (1922; Tony Grows Up), followed by Tonys läroår (1924; Tony’s Apprenticeship), and Tonys sista läroår (1926; Tony Finishes Her Apprenticeship).

Her first book, Ninas dagbok (1917; Nina’s Diary), a teenage novel, is written in a light, chatty style, as is Helenas första kärlek (1918; Helena’s First Love). At twenty-five, Krusenstjerna was still living a protected life with her retired parents in a Stockholm flat. Her series of autobiographical novels, revealingly entitled Fattigadel (Petty Nobility), contained a graphic depiction of the milieu in which she grew up: the old Swedish upper class that had retreated into the shadow of the rising, well-heeled middle class since the turn of the century and World War I.

All of Krusenstjerna’s works revolve around the feelings of coercion, desperation, and revolt that the world of her childhood fostered. The trilogy was a shocking departure from the typical teenager novel in exposing that which lay below the glossy surface of adolescent friendships, picnics, Christmas parties, and infatuations.

At its core are the taboo subjects of sexuality and mental illness. The reader is treated to a potpourri of everything that “a well-bred girl” is not supposed to know anything about, but ponders in the privacy of her own room: love, menstruation, homosexuality, prostitution, sensuality, and frustration. Each theme is presented as inherent to the world of an upper-class girl, as a painful step in her ‘apprenticeship’.

Tony grows up under the cloud of her mother’s mental illness. The lack of maternal affirmation is the deepest source of her alienation and the psychological problems that she ‘inherits’. On a literal level, mental illness is described as a predestined family curse to which women are particularly susceptible at the time of their first erotic experiences. But it can also be seen as a metaphor for the way that the emotional lives of young women are truncated when their needs are not given sufficient scope for expression.

Eventually, Tony winds up at a private mental institution. In her desperate confusion, torn between a commitment to her strictly correct fiancé and her desire for another man, she abandons herself to fits of aggression, sexual fantasies, and self-destructiveness. The sense of womanhood that she has acquired and internalised begins to waver: she no longer recognises herself in the mirror.

Tony grows up in her father’s house. After her mother’s death, they have a fond but not intimate relationship. Tonys sista läroår finds her making a radical attempt to escape. While in England, her first trip abroad on her own, she goes to see a travelling salesman who had courted her earlier. He takes her to a brothel. “Nothing that can happen between a man and woman is sacrosanct to me any longer,” Krusenstjerna wrote in her diary at the age of twenty-five, after having visited England.

“All at once I felt myself growing, blossoming. I was a woman and hadn’t known it. My trembling hands explored my body. A woman! The subtle curves of my breasts, the arch of my hips that enclosed a throbbing little vessel testified to my transformation. Mine was the humble art of acceptance; all my limbs were repositories of love. The world expanded before my eyes. My thoughts bored little holes in the wall and I peered into a strange and wonderful land. Suddenly I realised that I could create my own life.”

Tonys läroår (1924; Tony’s Apprenticeship).

An Erotic Labyrinth

At the time Krusenstjerna wrote the trilogy, she had finally left home. She married writer David Sprengel in 1921, the year that Swedish women gained the right to vote and run for office. He backed her career all the way and strengthened her resolve to write “truly bold books.” He was widely read in world literature, his ideal being French naturalism and early modern novels. Due to his influence, Krusenstjerna’s romantic style acquired a flavour of pungent realism, as reflected in the objective that she set for herself in a 1933 newspaper interview: “to write the truth about women”.

Her quest took her from the depressive chronicle of mental breakdown in the trilogy to a utopian dream of redemptive femininity at the end of the seven-volume Fröknarna von Pahlen (1930-1935; The Misses von Pahlen) cycle.

The Pahlen cycle consists of seven volumes:

I: Den blå rullgardinen (1930; The Blue Window Shade),

II: Kvinnogatan (1930; Street of Women),

III: Höstens skuggor (1931; The Shadows of Autumn),

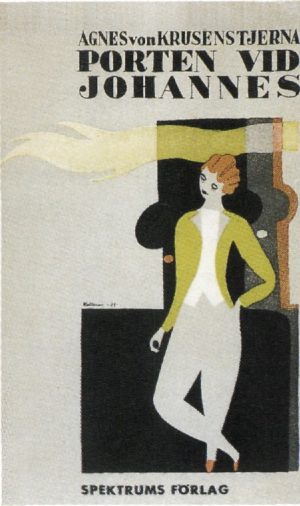

IV: Porten vid Johannes (1933; The Gate at Johannes),

V: Älskande par (1933; Loving Couples),

VI: Bröllop på Ekered (1935; Wedding at Ekered), and

VII: Av samma blod (1935; Of the Same Blood).

But it was a long journey. The heroines have fearful experiences as they “encounter every weed and flower of love and sexuality”, as Sprengel described the concept of the books. Such a goal resonated with the interest in the “dark realm” of unexplored drives and repressed desires that was so widespread at the time. The critics viewed the first two volumes, which were brought out in 1930, as a representative of primitivist, Freudian modernism.

Literary history still describes Krusenstjerna as a sexual Romantic and apostle of sensual love as the ultimate meaning of life. But things are more complicated than that. Her novels ask questions that women living through a period of sexual transition found both difficult and urgent: what role did sexuality play in female identity? How could women arrive at a life-affirming sensuality, free from the inherited baggage of sexual paranoia, misogyny, and denial of female desire?

Fröknarna von Pahlen is a far-flung panorama of women’s ever-shifting experiences as they seek answers to these questions. The trilogy was narrated in the first person; Fröknarna von Pahlen is more of a collective novel. The lives of fourteen different women are told, filtered through their various consciousnesses, separated as they were by age, setting, and circumstances. The central characters are Petra von Pahlen and Angela, the orphaned eleven-year-old niece whom she adopts at the age of twenty-seven. The novel chronicles their lives at Petra’s farm (named Eka) in the province of Småland as well as in Stockholm during World War I.

Krusenstjerna is famous for her insightful accounts of teenage girls and their sexual awakening, as embodied by Angela. Eventually she matures, falls in love, has her first relationship, gets pregnant, is abandoned by her lover, and gives birth at Eka with Petra’s help and support.

The portrait of Petra explores the world of older unmarried women and the issues they face. As a young woman, she is jilted by her fiancé. She retires to the farm she inherited from a childless aunt and severs her ties with the rest of the world. Adopting Angela brings a reprieve from her loneliness and melancholy: “She fell in love for a second time”.

“And there, her head in Angela’s lap, Petra’s temples no longer throbbed in bewilderment. She was neither a man nor a woman. She was a soul that had not yet felt the world’s chill and gloom enshroud her. Angela’s belly was gentle and soothing, the fountain of all existence, the root of everything that lived and grew. New generations would blossom forth. A whole universe would unleash its savage beauty from a little chamber of Angela’s being.

“And Angela stroked her hair as if she had already given birth and Petra was her child.”

(Bröllop på Ekered)

Throughout the Pahlen cycle, women’s desire shapes events under the surface. Never before had their sexuality been described in such an open, unadorned fashion, an abrupt break with the ideals of Romanticism as reinforced by Ellen Key’s concept of the “great love” as women’s ultimate goal in life.

“She was hollow inside. Her breasts were an empty vessel that longed to be filled. Love! Why not have the courage to admit it? She was hungry for love, one that stung and burned. A love that would fling her to earth with parted thighs, her groin throbbing in time with her simmering blood.

Somewhere under her skin was the real Petra von Pahlen. Not the silent, sedate, inoffensive creature that drifted through the monotony of life like a sleepwalker.”

(Höstens skuggor).

The cycle’s intricate composition is shorn up by the use of mirror images and doppelgängers. Adèle, the wife of a leaseholder, plays the role of a witch and ogre as a distorted projection of Petra’s anxiety at being sexually frustrated and smitten with “impure” desire. Imprisoned in a loveless, childless marriage, Adèle is the prey of her repressed libido. She pursues sex in an obsessed, hysterical manner – an uncanny perversion of the erotically generous mistresses who populated the books of male Romantics. The portrait of a wasted life, defined by self-contempt and helplessness, is both powerful and frightening. On a symbolic level, Adèle increasingly becomes Petra’s alter ego, the incarnation of everything she fears and despises in herself. Even in terms of the plot, they are both attracted to the same man – the leaseholder Tord Holmström.

One of the many ways to read Fröknarna von Pahlen is as a coming-of-age novel in which Petra – torn between irreconcilable concepts of womanhood – seeks wholeness and an identity of her own. Angela can be interpreted as a projection of the aspects of Petra that traditionally characterise the ‘good woman’. Petra’s project is to transcend these stereotypes and forge a more complex, integrated, and personal female identity.

Recapping the plot of Fröknarna von Pahlen with all its literal and symbolic twists and turns would be a hopeless task. The reader is often lost in the “erotic labyrinth” that Petra talks about in the last volume and that a letter from Karl Otto Bonnier reproached Krusenstjerna for having created out of a perverse interest in degenerate art. But the ‘truths’ that the cycle reveals are not on the level of intrigue. The books deserve to be read as a complex psychodrama, an exploration of the inner chambers of female passion.

Petra and Angela are often described as reflected images that merge with each other. They are also similar on the physical plane; frequently, it is as though they are projections of the same woman at different stages of life. As had been the case with Adèle, Petra is attracted to the same man as Angela. Thomas Meller, her ex-fiancé and the love of her life, returns to Sweden in Volume IV after fourteen years abroad. He sees in the nineteen-year-old Angela the girl whom he once loved; the older woman is invisible to him. Youth and beauty are the traits he regards as most worthy of his affection.

The relationship between Angela and Thomas is traumatic for Petra. Angela becomes a kind of deputy for her, an extension of herself. Once more, desire conflates the two women into a single being: “Sometimes Petra felt that she was united with Angela in some kind of mysterious way. Angela dwelt inside her. She turned into two people: while one blazed with the heat of Thomas’s kisses, the lips of the other remained cold as ice.”

In her best moments, Krusenstjerna finds a persuasive language to describe such infernal mechanisms of desire. The strength of her storytelling is the ability to portray repressed and forbidden feelings, the secret of its suggestiveness and appeal, as well as its power to offend, alarm, and disgust the reader. She crosses all boundaries. Different characters dissolve, duplicate, become one. Without flinching, she depicts passion that is ready and willing to descend on the least suspecting victims: siblings, men and men, women and women.

The House of the Good Mother

Women’s emancipation was a major topic of public discussion when Krusenstjerna wrote the Pahlen cycle in the early 1930s. “Voluntary motherhood” was a slogan of radical feminists, including the Tidevarv Group and the Swedish Association for Sexuality Education (RFSU). Single mothers were the heroines of many novels by women around that time. Angela’s joy at having a child out of wedlock was totally à la mode in terms of both literature and reality.

A few landmarks for the Swedish women’s movement: 1921. Universal suffrage and the right to run for political office. Married women are legally competent at the age of twenty-one.

1925. Women are entitled to civil service employment (with the exception of clergy, soldiers, and judges). 1937. Means-tested child allowance, parents’ allowance, free maternity care. Adultery is no longer a criminal offence. Being the younger party in an incestuous relationship is decriminalised. 1938 Sales of contraceptives permitted. Limited right of abortion for medical reasons. 1939. Dismissing women employees due to marriage or pregnancy is outlawed. 1944. Homosexual relationships between adults are decriminalised.

It was hardly the theme that upset the public to the point that demands were heard for the last two volumes of Fröknarna von Pahlen to be censored and banned. The greatest challenge to prevailing social norms was the decision by her characters to turn their backs on men and accept full responsibility for the lives of their children. “Owning a child without the involvement of a man must be a woman’s greatest happiness”, Petra says, offering to take care of Angela and the child she is carrying. Presumably based on the lives of ancient goddesses, she wants to create a “holy little family of two women and a child”.

It turns into a whole matrilineal clan when two other pregnant women appear on the scene. Agda and Frideborg are illegitimate offspring, each with her own father, of Eka’s previous proprietress. Acknowledging them as heirs “due to their mother’s blood”, Petra allows them to live and give birth at Eka. A new dynasty is in the making, with Eka as the ancestral estate: “Eka was to become a great, loving domain for women and children”. Though childless herself, Petra becomes the “progenitress of a new and happy family”. Angela and the child she is expecting are the sole objects of her passion. The young woman’s womb is the centre of her universe.

The House of the Evil Mother

Krusenstjerna’s last novel cycle, Fattigadel, is a caustic, painful confrontation with the conservative upper-class home in which she grew up. She traces Viveka von Lagercrona’s life from her earliest memories until she prepares herself at the age of twenty to leave the multifaceted and bustling, but stuffy and fractious, life that she shares with her parents and her three older brothers.

Fattigadel (Petty Nobility) consists of the following volumes:

I: Fattigadel (1935; Petty Nobility),

II: Dunklet mellan träden (1936; Dusk between the Trees),

III: Dessa lyckliga år (1937; These Happy Years), and

IV: I livets vår (1938; In the Spring of Life).

The book goes head to head with the concept of ‘the good mother’, the angel of the household, protectress of children, bulwark of family life. Viveka has a nightmare when she is a little girl: her mother leans over her bed with a big iron in her hands “in order to iron out all her wrinkles so she’ll be just like everyone else”. Waking up, she screams “at the top of her voice”:

“‘Mommy is a witch! Mommy is a witch!’” Her outcry could serve as the slogan for the whole series.

Viveka has nightmares about her mother even after she grows up. As if in a horror film, she pursues the fleeing figure of a woman through the darkness. She thinks that it is the sister she always yearned for but never had. On top of a high precipice, she catches up with the creature, who turns around – and she looks with terror into the face of her mother. She is seized by rage and strikes her mother so hard in the chest that she shrieks and falls over the edge. The symbolic murder of ‘the evil mother’ marks the end of that particular conflict in Fattigadel.

But the cycle contains much more. Fattigadel is Krusenstjerna’s most vibrant work – a teeming family saga in which each character has a distinctive persona and the meticulous descriptions are evocative, credible down to the smallest detail. Colonel von Lagercrona is one of the most loving and masterful portraits of a father in Swedish literature. Gentle, taciturn, deeply honest, and old-fashioned, he represents everything that Krusenstjerna esteemed in men: solicitude, thoughtfulness, and tenderness; love of children, animals, and nature.

Krusenstjerna was still planning to write at least one more volume of Fattigadel when she fell ill as the result of what turned out to be a brain tumour. She died on the operating table in March 1940 at the age of forty-five.

The Battle over Sex

“We find it deplorable that women would plead for the breakdown of the family in such a manner. It is unnatural and socially destructive, since everyone knows that society cannot survive without a foundation of strong homes and families that are based on loyalty and responsibility.”

(editorial in the newspaper Svenska Morgonbladet, 30 January 1934).

The women who were singled out for attack by the Christian-minded newspaper were authors Agnes von Krusenstjerna and Karin Boye. The article was the opening shot of a heated and rancorous debate about literature and morality that lasted for more than two years. The core issue was the right of women to speak out about the most burning issue of the day: whether the prevailing sexual morality was too restrictive.

The radical young authors who fought for freedom from censorship defended Krusenstjerna’s books. But she was ambushed from many different directions. In addition to media barbs, the debate featured a 126,000-name petition demanding the establishment of a government censorship board that was turned down by the Minister for Justice, motions to the Parliament, proclamations by the Church, and public meetings.

The controversy was to go down in literary history as the Krusenstjerna or Pahlen Feud. The first three volumes of the novel cycle had been brought out in 1930-1932 by the well-known Albert Bonnier’s Publishers. After Volumes four and five had already been composed for printing, however, Bonnier’s suddenly backed out in autumn 1932. Karl Otto Bonnier wrote to Krusenstjerna: “In their current condition, I neither can nor dare bring out these volumes, not only because I despise tastelessness and everything that is against nature, but because my publishing house would suffer irreparable injury.”

The expression “against nature” appears to have been lifted from Section 18:10 of the Penal Code, which prescribed two years of penal servitude for homosexuality or incest. Those were the passages that Bonnier wanted removed.

Krusenstjerna staunchly rejected any and all censorship, and the discussion went back and forth throughout 1933. The two volumes Porten vid Johannes (The Gate at Johannes) and Älskande par (Loving Couples) were finally brought out by the brand new Spektrum Publishers, which was associated with the radical cultural magazine of the same name.

The critics for the major newspapers unanimously ignored the books. The silence was broken on 28 January 1934, when Boye published a major article in Social-Demokraten entitled “Då vinden vänder sig” (When the Winds Change). “Why this neglect of an author who has previously been so highly esteemed by both critics and the public? The deathly silence is like the shroud that well-disposed middle-aged men wrap around the indiscretions of a nervous young woman about whom they once had nothing but good to say”.

According to Boye, Krusenstjerna’s portrayals of both society in general and women in particular were challenging and revolutionary. She summarised their message: “Social conventions are disintegrating all around us – that is the conclusion that can be drawn from Fröknarna von Pahlen. The institution of the family is breaking down, along with the entire system of morality that had crystallised around it.” That Krusenstjerna’s bold exhibition of the vacuity inherent to traditional sexual morality attracted so little attention demonstrated “that we have entered a period of cultural reaction”. Boye drew parallels to censorship and book burnings in Nazi Germany.

Two days later, on the anniversary of Hitler’s appointment as Chancellor, Svenska Morgonbladet took up the gauntlet and recommended the same kind of measures that he had already adopted:

“It’s not difficult to understand the bitterness that has welled up in Germany against all this decadent literature, with or without the hallmark of Marxism, and that has led people to collect and publicly burn heaps of this repulsive trash.”

A 1937 essay by Hagar Olsson explores the roots of Krusenstjerna’s art:

“The spiritual significance of her oeuvre is its revelation of a profound personal struggle, a quest for a truth about the human condition that eludes artists unless they plumb the depths of their own being. The path was never easy, and the psychological methods of our age may make it more treacherous than ever. The indomitable faith in life and intense longing for beauty and harmony that sustain Krusenstjerna’s writing have been purchased at a tragically high price. “These pages are stained with blood from a deeply enigmatic nature.” The essay was reprinted in Olsson’s Jag lever (1948; I’m Alive).

Translated by Ken Schubert