With Män kan inte våldtas (1975; Men Cannot Be Raped; Eng. tr. Manrape), Märta Tikkanen hurled herself headlong into the ongoing discussion of gender roles. The tale of the conventional Tova, who is raped on her fortieth birthday and changes from a proper, single mum to a whipping angel of vengeance, was a thriller suited to the time. It rolls along on hardboiled and efficient prose, rumbles with rage, and is carried by rough irony. The details of the unlikely story, describing how a woman avenges the male rape an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth, are carved out with merciless clarity. It is the tale of a single case, a private story, that gradually takes on a more common cause. The story of Tove’s act of revenge is successively transformed into an accusation against, not just one man, but the entire patriarchal society.

The Nordic Council Literature Prize was instituted in 1962. In 1979 Norwegian women ran a collection for an alternative award for Märta Tikkanen, the Nordic Women’s Literary Award, protesting that the Nordic Council Literature Prize had been awarded exclusively to men. The next year, in 1980, it was awarded to Sara Lidman as the first woman recipient. Since then, Herbjørg Wassmo (1987), Frida A. Sigurðardóttir (1992), Kerstin Ekman (1994), and Dorrit Willumsen (1997) have been awarded the Literature Prize; five women in thirty-five years.

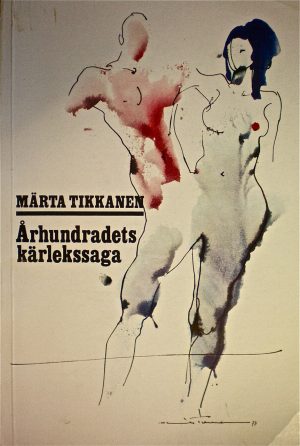

With Män kan inte våldtas, Märta Tikkanen became one of the figurehead writers of the new women’s movement, not just in her native Finland but in all of the Nordic countries. In a number of books she would thematise not just a series of acute women’s problems, but also – or above all – her own private life story in a way that met with great response. It is not until her next book, the collection of poems Århundradets kärlekssaga (1978; Eng. tr. The Love Story of the Century) that she gains her incontestable status and reaches a truly wide readership.

Århundradets kärlekssaga is a report from the inner depths of a marriage of drunks. Many of the poems are shaped like direct speech. In a marriage in which communication has ceased and all words have become distorted, the wife, as a last resort, hands her pieces of paper to her real-life husband, the artist Henrik Tikkanen. “I think that you have failed me / that you have no / use for me as I am / but have changed me into a sprite”, Märta Tikkanen writes. “I don’t know / how to get past / my disappointment.”

“We want bread and roses too”, the striking working women sang in early twentieth century America. The new women’s movement made the slogan theirs, and in what is perhaps the most quoted poem in Århundradets kärlekssaga (1978; Eng. tr. The Love Story of the Century), Märta Tikkanen gives it yet another twist.

Keep your roses

set the table

instead

keep your roses

lie a little less

instead

keep your roses

hear what I say

instead

love me less

believe in me more

Keep your roses!

The Tikkanen couple had for long been in an artistic dialogue. Henrik Tikkanen’s response to Märta Tikkanen’s debut novel nu imorron (1970; now tomorrow), which was unmistakably autobiographical, was made in his drawings, but eventually Henrik Tikkanen also entered into a literary dialogue with his wife. And her Århundradets kärlekssaga can be read as a reply to his autobiographical Mariegatan 26 Kronohagen (1977; 26 Mariegaten Street, Kronohagen), which had been published the previous year. He depicts his wife Märta as a miracle of strength, endurance, and love. She has all the determination and firmness of character, the permeating, all-encompassing ability to love, that he himself lacks. She is his fixed point, the eternally waiting, utterly tolerant, beloved woman, and there is an iconographical shimmer around her in the final image of the novel, where he at long last returns home after a European tour of revelry. “She was at home and although it was late she was up as if she had been expecting me”, he writes. “I love you so incredibly / you said”, Märta Tikkanen quotes her husband in Århundradets kärlekssaga:

Nobody has ever been able to love like me

I have built a pyramid of my love

you said

I have placed you on a pedestal

High up above the clouds

This is the love story of the century

you said

it will always exist

to be eternally admired

The irony is thick, and time and again Märta Tikkanen drags the collection’s title through the mud. But she also acknowledges it time and again. Their love story is that of the century. But now she wishes to tell – him and everyone else – what it costs a woman to go through something like that. She opens the door to the private hell of the wife of an alcoholic, and piece by piece a stench of bodily odours, un-brushed teeth, and vomit envelops her husband. She puts the most appalling things into words, unemotionally, without shying away from any of the demeaning details. And yet these are poems filled with a strange warmth. “You were my longing / to take and give”, the text says, and formulates the ideal love that runs as a refrain through all of Märta Tikkanen’s works: “You were the one I wished to walk abreast with”. In the next breath she tells about denigration, and Århundradets kärlekssaga swings in very precise rhythms back and forth like a sorrowful and scratchy two-note blues, in which hateful accusations and descriptions of misery break against nostalgia, flaming love, and great longing.

Märta Tikkanen did not just formulate a series of women’s problems during the 1970s. She was also the poet of happy endings. In her novels and poems there is always a hope, a Utopia. By the end of Män kan inte våldtas (1975; Men Cannot Be Raped; Eng. tr. Manrape) Märta Tikkanen transgresses the harsh political gender polarisation of her story by bringing Tove’s beloved son into the story. In Århundradets kärlekssaga, the last third of the tripartite collection allows the reader to glean a female departure and sisterhood as a way out. In work after work, Märta Tikkanen opens her stories on the very last pages to express a completely incorruptible belief in life’s healing powers and the ability of humankind to rise above denigration.

Märta Tikkanen is in many ways the private confession’s poet. Her writings are basically a reworking of her ongoing life. She writes her life-text over and over again, writes it and rewrites it. The project began in 1970 with the debut nu imorron. It is dedicated “to my dishwasher of the brand constructa” and depicts a mother of little children who does everything to get a single week to herself: she even finds another woman for her husband. Well rid of the very trying, somewhat alcoholic, and erotically untrustworthy – as-yet unnamed – husband, the children are taken ill and have to stay at home from kindergarten. On top of that the wife is infected with jealousy and spends a great deal of time wondering about her husband’s possible infidelity.

The path to the longed for typewriter is long, but nevertheless nu imorron (1970; now tomorrow) is clearly a text defining an emerging author. The text is organised around the meeting between the woman and the typewriter that just does not come off. The mother of young children, the author’s alter ego, is trapped in a world of dust and dishes, sick children and a needy husband, chased by an indomitable longing for that time of her own that will give her a text of her own. And the novel can in many ways be read as a victory over the life it describes. In her two next novels, Ingenmansland (1972; No Man’s Land) and Vem bryr sig om Doris Mihailov? (1974; Who Cares about Doris Mihailov?), Märta Tikkanen develops the stifled woman’s life and the problems of imprisonment even further, but now in purely fictive form. Fredrika in Ingenmansland is locked away not just in her servile role of wife, but also in a coupledom that threatens to engulf her. Clara in Vem bryr sig om Doris Mihailov? is captured in the lies of an open marriage. Doris, the absent title character of the novel, is a singularly unstable and generally failed single mother, who has been placed in quarantine. Just like Tove in Män kan inte våldtas, they are defined by the male society’s texts and structures. Fredrika attempts to liberate herself through political commitment, Clara gets on with her career, and Doris flies into antisocial behaviour and aggression. They work hard to get out of their respective prisons, but even though the door to the woman’s prison always seems to open ajar in the last few pages of Märta Tikkanen’s books, and you sense a rebellion, the texts themselves only depict various types of female conformity and submission.

“Why don’t you leave?” the writer’s alter ego asks herself in the first poem of Århundradets kärlekssaga. In book after book, Märta Tikkanen investigates the ties that bind women – or herself, often she speaks very autobiographically – to husband, children, lovers, and parents. “Where is the logic?” she asks herself in Rödluvan (1986; Red Riding Hood). “nowhere / it is too awkward”, she replies. But in this, as in many other novels and poems, Märta Tikkanen systematically works her way through layer after layer of ties in order to, if possible, find the story of logic in the lives of women. The collections of poems Mörkret som ger glädjen djup (1981; The Darkness that Deepens Joy) and Sofias egen bok (1982; Sofia’s Own Book), are about ties to a sick child. Storfångaren (1989; The Great Trapper) and Arnaía kastad i havet (1992; Arnaía Cast into the Sea) are about relationships with a new man.

Rödluvan, spanning a whole lifetime, is perhaps the most extensive of these investigations. In fragmented and tentative form, it depicts a girl’s development from child to adult. Much of the story is recognisable from Märta Tikkanen’s previous books, but the narrative is still new. Death has ended the love story of the century and it must be rewritten and reinterpreted. Märta Tikkanen writes it indirectly, as a reworking of the old fairy-tale about Little Red Riding Hood and the Big Bad Wolf, but it is not just the old tale that is rewritten, it is also the love story of the century. In Märta Tikkanen’s Rödluvan it is the girl who rushes ahead into the woods. She knows that she wants her Wolf and lures him with her. The roles of the fairy-tale are reversed. The Wolf is mad and lovely (when he is not drinking) and mother is pleased. The Red Riding Hood daughter will be doing what the mother never dared: meeting male violence, liberating herself, and getting a room of her own. The text works through association, with the course of life as fixed points and the two tales, Little Red Riding Hood and the Love Story of the Century, as sounding boards.

“Have you had enough of wolves, will you chose another kind of man for your life now?” a woman asked Märta Tikkanen at a writer’s evening in Nuuk in Greenland. The question is repeated in the novel Storfångaren, as is her ‘no’. In this novel and in Arnaía kastad i havet, Märta Tikkanen progresses with her investigation of the mysterious logic of love and emotions. Both books tell the same love story, but approach it from two completely different angles. In Storfångaren the text meanders in associative curls towards a meeting that is also a parting. In Arnaía kastad i havet Tikkanen approaches the double grief of a lost husband and a lover who turns from her. Like a wide-meshed net Märta Tikkanen first throws the Greenlandic folk song about the great trapper who would not let himself be trapped on top of her own private love story. Then she attempts to catch it by using the myth of Icarus’ daughter Arnaía, who was identical with Odysseus’ wife Penelope.

According to Robert Graves in Greek Myths, Arnaía is identical with Odysseus’ wife Penelope. She was cast into the sea on the orders of her father, Icarus, but was rescued by a flock of striped seabirds, which gave her a new name: Penelope – Duckfowl, The Striped One, or She Who Wears a Net over Her Face.

The Penelope, we know from Homer’s Odyssey, waits faithfully for her husband. Each night she rips up part of her weaving to be rid of the waiting suitors. In Märta Tikkanen’s Arnaía kastad i havet (1992; Arnaía Cast into the Sea), in which the myth merges with the writer’s own life story, she has long forgotten her journeying husband. In fact, she stopped loving him before he even left. Her whole longing is for Amfionos, the handsomest of her suitors, only he refuses to oblige her.

“The private is political!” was the new slogan for women’s liberation, and one may say that Märta Tikkanen writes her program full, even after literary trends have started to blow in other directions. In the midst of time, in the midst of life, she not only translates her own experience in a congenial way, but also clearly voices something that has been a long time in the telling. Time and again she seeks to capture the female life-text, her life story, just to show the impossibility of the project. She continually approaches her story in new ways, and throughout her oeuvre one can trace how her approach becomes increasingly complex and sophisticated. The faith of the early 1970s in direct designation, the belief that experience could be transferred to paper, must make way for a far more indirect and tentative manner of approach to the experiences that are to be described. The genres are rolled up, poetry becomes prose, prose becomes poetry, travel writing becomes love story, love story becomes myth. The text of her life must be continually rewritten, continually renamed.

Translated by Marthe Seiden