In January 1684 Racine’s play Iphigénie, written nine years earlier, was performed in the Wrangelska Palats (Wrangel Palace) in Stockholm. The royal family and court attended; the participants in the play were all young ladies of the court led by the instigator of the project, Maria Aurora von Königsmarck. The production attracted a lot of attention; poems were written in tribute, with Sophia Elisabet Brenner praising the women here in “our cold North” for showing off their skills. Posterity has also looked with interest on the production of Iphigénie, and wondered why a group of aristocratic women in Stockholm decided to put on the play and force a reluctant King Karl XI to watch it. Was it a political display by the pro-French faction in the nation’s capital? Was it an attempt to introduce the court to the modern era and French tastes? Or can performance of the play be seen as a manifestation of intellectual kinship with the French salons of the day?

Iphigénie is about a king’s daughter who must be sacrificed for the men’s war. In the seventeenth century the court theatre fulfilled an openly representative function, and it would not be in the least far-fetched to imagine that the king’s daughter of the play alludes to the Danish king’s daughter who had to wait five years after her engagement before she could be married to the Swedish king and become the queen of Sweden – all because of war between the two countries. This fact alone would suggest resistance to men’s power and women’s lack of freedom. Another factor points in the same direction: all the roles were played by women, including the ‘heavyweight’ male roles of Achille and Agamemnon. Women also took part in ballets performed at court, as goddesses or personified virtues. Similarly, they had appeared in what were known as “värdskapen” (a kind of costume ball) held at court, but in these they only played the female roles, whereas in the performance of Iphigénie they played all the roles, dressed as men, indeed even as warriors. The women thus enjoyed the same status as the men. And the operatic framework in which Aurora Königsmarck set the drama called on the services of eleven dancing amazons.

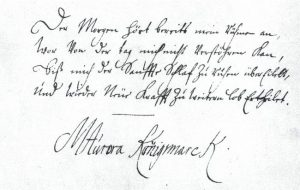

Aurora Königsmarck (1662-1728) had already written an opera libretto, performed at the Hamburg Opera, by the time she was eighteen years old. The plot turned on how a number of women used various strategies to reject love in favour of personal freedom – a topical message in the salons of les précieuses in France. Aurora Königsmarck was well-read in the modern French literature and matters of current interest. This is especially apparent from her descriptions of the aristocracy at play, “Les divertissements de Medevi”, written at the new ‘health spa’ in Medevi. In this we find references to literature written for the modern French woman of the day.

Aurora Königsmarck’s life would also seem to have been shaped by ideas of women’s will to challenge the limitations imposed on them by the conventions of the era. For example, she never married because, according to contemporaneous reports, she simply did not want to. She was renowned for her beauty and her various talents, and she did not lack suitors. Her brother, Filip Christopher Königsmarck, was well-aware of his sister’s views on this subject and wrote, in an apparently teasing tone: “Seeing as everyone who wishes to contract marriage with you applies themselves to me, I must hereby advise you that a man has now come forward, he is thirty years of age, well-educated, of good social standing and an annual income of 16,000 riksdaler [rix-dollars] and will present you with a wedding gift of 80,000 riksdaler.” But Aurora preferred freedom. She acknowledged as hers the son she bore August the Strong of Poland; she had the child baptised in Goslar with leading townsmen as his godfathers, looked after him and brought him up herself, the latter task not being without its difficulties. In 1698 she moved to the Kaiserlich freie weltliche Reichsstift Quedlinburg (Free Secular Imperial Abbey of Quedlinburg), and two years later she was appointed prioress. Maria Aurora Königsmarck’s autobiography, Meditations et Memoires, dictated to her spiritual adviser von der Schulenburg, was found in 1912, in an attic of a rectory in the town. However, when the descendant of von der Schulenburg who made the discovery returned to the attic to study the interesting 200-year-old manuscript more closely, he found that it had vanished. Perhaps the fêted and famous noblewoman’s thoughts on being female in seventeenth-century Europe would have been revealed in her memoirs.

Besides Aurora, a few other ladies of the court who participated in the 1684 performance of Iphigénie should be mentioned here: her sister Amalia Wilhelmina Königsmarck (1663-1740) played the role of Achille in Racine’s dramatic tragedy, and their cousins Ebba Maria de la Gardie (1657-1697) and Johanna Eleonora de la Gardie (1661-1709) also took part. Along with the somewhat older baroness Märta Berendes (1639-1717), these women were the queen’s inner circle of friends. They shared Ulrika Eleonora’s scholarly and artistic interests, and also her piety. The group has been called an “ecclesiola i kongeborgen” (a little church in the royal castle), and they cultivated the intense piety that was a powerful undercurrent in seventeenth-century devotional life – as often as not, that of this very aristocracy, its women in particular.

The oldest of the group, Märta Berendes, would most likely have passed on quite a lot of this piety to Ulrika Eleonora, the princess who lost her mother at an early age and would later become queen. And Märta Berendes remained at court until her death in 1717. Widowed at the early age of thirty-seven, and with many children, she started writing; her poetry and reflections express her despair, but also her deep trust in God. Her poetry reveals more of the person behind the words than was usual in the literature of the time:

Jag ensam är hvart jag månd gå

Med barnen, små och späda,

Som man och fader sakna må,

Ja, alt hvad hiertat gläda.

Men Herren sielf, som lofvat har

Rätt faders stad förträda

Han blifver ock vist mitt forsvar

Hielper min axlar späda

Att bära, hvad hans hand sa mild

Mig har täckts att pålasta

Ty iag af mig till honom vill

Från verldzens svijk sielf hasta.

The two sets of sisters/cousins, seemingly trendsetters in court circles, also showed their scholarship and artistic refinement by conveying their thoughts in the form of poetry. Quite a lot of the literary works produced by this court coterie – written for the close circle of friends and probably not with any thought to publication – are gathered in Nordische Weihrauch, oder zusammengesuchte Andachten von schwedischen Frauenzimmern (The Nordic Incense, or Collected Devotions of Swedish Women), a manuscript put together by Aurora Königsmarck. Besides conventional panegyric poetry, the collection also contains poems written in German or French, expressing a longing for heaven and disdain for the external splendour of earthly life. Even though the century boasts many a rejection of the superficial life of town or court, there is reason to wonder about the cause of this boredom and why these intelligent and learned women would spurn worldly life.

In seventeenth-century Europe, a number of spiritual movements were critical of, or even in direct opposition to, the established Churches. It is hardly surprising that Descartes, who had taught his contemporaries to turn inherited concepts upside down, wielded influence over the leading figures of these circles. In this the women played a role of no little consequence. August Hermann Francke, who succeeded Philipp Jacob Spener as the leader of Pietism, offered places for girls in four of the schools he established in Halle; earlier, in Frankfurt, what was known as Saalhof Pietism had been of great significance to the religious emancipation of women. These movements were opposed to overly heavy-handed dogmatics and preferred to set store by personal experience; thus the women, with their experience of the presence of God and despite the lack of any solid education, could contribute on equal terms with men. The religious community thus offered the freedom and sense of worth unobtainable in the wider community with its established gender roles. Ulrika Eleonora’s court circle was in contact with key figures in the Pietistic reform movement, and was thus a parallel to the spiritual movements on the continent, which were attempting to put the demand of freedom and human worth for the woman into practice.

Philipp Jacob Spener (1635-1705) advocated a practical and vibrant Christianity, and stressed the importance of the layman and the need to restructure clerical training. His Pia desideria, originally written as the preface for an edition of Johann Arndt’s book of sermons, led to the appellation “Pietists” for those who shared Spener’s views.

Many poems in Der Nordische Weihrauch manifest distaste for the pomp and splendour of court life and reveal a focus on the inner person.

Gott mach’ mich frey, in diesem armen Leben

Kann ich mich dir nicht wie ich will ergeben,

D’rum reisse doch einmal das Band entzwey.

Ich bin die Welt und all ihr Thun so müde,

Mein Geist, der seufzt und sehnet sich nach Friede,

Gott mach’ ihn frey!

God, make me free, in this poor life

I cannot surrender myself to you as I do wish,

therefore tear the bond once more asunder.

I am so tired of the world and all its pains,

my spirit, sighing and yearning for peace,

God, make it free!

Here Johanna Eleonora de la Gardie is expressing neither melancholy nor sectarian disdain for the world, but the same longing for true freedom that motivated the production of Racine’s tragic play Iphigénie in Wrangelska Palats in Stockholm in January 1684.

Translated by Gaye Kynoch