The authors of ecclesiastical history tend to be theologians and church leaders. Traditionally speaking, they are usually men, and women play a relatively obscure role in their writings. But many women were active in the multitude of revival movements that sprang up in the nineteenth century. New structures gave rise to different kinds of literature, and the spiritual currents of the Nordic countries rippled with female writers, hymnists, and preachers.

Haugianism

Berthe Canutte Aarflot (1795-1859) was born in the countryside of Ørsta, Norway. She grew up in a stimulating spiritual and cultural milieu with ready access to books and daily exposure to old devotional literature and hymnals. She married at the age of twenty-one and became a busy farm wife. In the early 1820s, a Haugian preacher by the name of Amund Brekke arrived in Ørsta, and Aarflot underwent a religious conversion. Berte Kanutte Sivertsdatter Aarflots Selvbiografi, indholdende Optegnelser om hendes aandelige Livs Udvikling etc. (1860; The Autobiography of Berte Kanutte Sivertsdatter Aarflot, Containing Notes about the Development of her Spiritual Life, etc.), published the year after her death, relates that she was doing her chores one day when she overheard Brekke talking to others in the household and suddenly “saw the light”. Like other Haugians, Aarflot felt a strong connection with the devotional literature of the older Lutheranism and its vigorous hymn tradition: “As soon as I began to sing, it was as though the Holy Spirit had suddenly opened my sealed heart so that the word had a special power and impact, and I felt such a sweet sensation in my soul that I will never forget it. It was as though the entire song belonged to me and reflected my condition.”

She began to write her own hymns, several collections of which were published throughout the nineteenth century, at an early age. Nine editions of Troens Frugt: en Samling af aandelige Sange (The Fruits of Faith: A Collection of Spiritual Songs) were printed from the 1830s to 1874. Aarflot was among the most gifted of the many Haugian hymnists. She carried on the tradition of Thomas Kingo and Dorothe Engelbretsdatter, whose Siælens Sang-Offer (1678; Song Offering of the Soul), was one of the most popular spiritual works in Haugian circles. Her enforced dependence on diction that differed from spoken Norwegian, however, inhibited her, compromising the independence of what she wrote in relation to her antecedents. She frequently offered prayers, and occasionally inspiring witness, at Hungian gatherings in her district, but she was otherwise most effective behind the scenes. She is said to have helped many people in her role as a spiritual guide.

The hymns of Dorothe Engelbretsdatter (1634-1716) were integral to the vibrant devotional literature of Denmark and Norway. Thirty editions ofSiælens Sang-Offer (1678; Song Offering of the Soul), her first work, were published over a span of two hundred years.

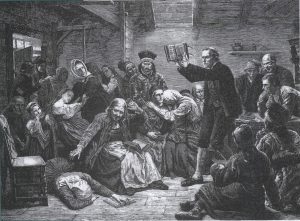

As a major ingredient of Norwegian spiritual and cultural life, Haugianism was one of the many Nordic revival movements that emerged in the nineteenth century. Hauge’s peregrinations around the country won him many followers (“friends” as they referred to themselves), almost exclusively peasants and farmers. His fluent pen also attracted many readers, contributing to the movement’s growth and persuasive power. While he stressed the importance of penance and conversion, his focus on the Christian’s calling in earthly matters was also typical of the revivalists. In an apparent paradox, the conflict between the “world” and “life in God” was resolved by a dutiful commitment to daily effort and social responsibility. Thus, Haugianism was also part of the business and political scenes in Norway. The growing prominence of laymen in public life was a related phenomenon. Although the law was still in effect and Hauge received a long prison sentence for violating it, many of his followers were travelling preachers or served as spiritual leaders at the conventicles of those who had seen the light.

Larine Olsdatter Øxne (?–1803), who had been moved by the preaching of Hans Nielsen Hauge (1771-1824), wrote of her need for a new life:

Now it is high time for me

To awaken

Who slept so long

in the fog of sin;

I have not walked the path,

Which rightly I should have run,

But oppressed the Spirit of God

Haugianism paved the way for Camilla Collett’s indefatigable struggle and for other forces of women’s liberation in Norway. Particularly in the early stages of the movement, women played a relatively prominent role, even as preachers. The literature takes notice of women’s involvement. Hauge’s Om religiøse Følelser og deres Værd (1817; Religious Feelings and Their Worth) includes autobiographical narratives that are written in letter form and concentrate on life’s spiritual aspects. A third of the eighteen contributors were women, either farm wives or maidservants. When Aarflot recorded her memories and experiences towards the end of her life, she was thus following a kindred literary tradition.

Typical Characteristics of Nineteenth Century Revival Movements

Due largely to shifting economic and social circumstances, the ecclesiastical histories of the various Nordic countries differed considerably. Their spiritual currents, whether revival movements or not, also took different directions. Proceeding from the example of Norway and Aarflot’s role there, several typical characteristics can nevertheless be identified, hopefully without engaging in unfounded generalisations. First, there was a streak of protest. Enlightenment rationalism, which shaped theology and a great deal of preaching for much of the nineteenth century, sparked a reaction, including demands for more vigorous evangelism and active Bible reading. The rich canon of devotional literature acquired a new lease on life. The protests were often directed at pastors, who were criticised for lack of religious rigour and exemplary conduct. Revivalists tended to view them as representatives of government authorities that used laws and other instruments of control to maintain their monopoly on religious practice. As old social structures evaporated, collective religion was replaced by individual experience and belief. Preachers stressed conversion, and believers gathered at their own conventicles. Although Hauge never renounced the church and ministry, stressing their stewardship of the sacraments, others rejected traditional worship services and even celebrated communion separately. The trend was particularly evident in districts where revival movements channelled indirect social criticism of a group that could not obtain a hearing any other way. The local pastor’s attitude towards revivalism played a significant role as well. Many of them felt that it enriched the spirituality of the church and they became central figures themselves, whereas others feared a schism and tried to preserve the old, unquestioned ideology.

Whether revivalism stemmed from burgeoning class consciousness among peasants and farmers or from the growing proletariat of an agrarian society in flux, the stage was set for acknowledgement of lay co-responsibility for Christian life at both the church and congregation levels.

The Conventicle Act of 1741 in Denmark-Norway and 1726 in Sweden prohibited meetings that had not been arranged by the church, unless a pastor was in charge. Demands for tolerance during the Enlightenment had limited any meddling with such conventicles, but zealous pastors who looked to the stringencies of Orthodoxy as an ideal led to a backlash in the nineteenth century. The Haugians worked hard to repeal the law and finally succeeded in 1842. Sweden followed suit in 1858.

The idea of religiously competent laypeople encouraged democratic thinking, and training in speaking before a group was frequently useful in other areas of social involvement.

Danish lay preachers Rasmus Sørensen and Peder Hansen were leading agitators for improving the conditions of the peasantry. Rasmus Sørensen was the editor of Almuevennen (1842), the peasantry’s first political mouthpiece, and a prominent, controversial figure during the hectic days of March 1848. A number of leading Haugians were at Eidsvoll in 1814 when the national assembly proclaimed Norway’s independence, as well as at the first Parliament. Seeing the light or undergoing conversion was to permit a more conscious and righteous life, the “fruit of faith”.

It is not very surprising then that the laity, women in particular, played an active role in revival movements. The congregations that were eventually formed granted them the right to vote and hold office long before society as a whole did. The key and equal role that women played in Haugianism was largely due to the fact that they were integral to production in agrarian society, where the movement originated. In the case of other movements, some of the explanation had to do with a society that was in flux. Agrarian reforms, crop failures, demographic growth, an expanding landless and servant population, and a surplus of women marked the early nineteenth century. Many people sought their identities in community, which the new spiritual movements and their activities could offer.

Female Preachers

Women are frequently mentioned in connection with the early revival movements that stressed ecstatic experience. Anna Michelsdotter Rogel was well known in Finland during the second half of the eighteenth century. Karolina Utrainen (1843-?), who preached a hundred years later, attracted large numbers of listeners wherever she went. A remarkable dream she had at the age of nine was eventually printed and disseminated widely. The story, which she had written down on her own, resembles John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress (1678) in its descriptions of Heaven and Hell. Her sermons, which she delivered in a trance-like state at the same time early each morning, reflected thoughts and doctrines that Paavo Ruotsalainen (1777-1852) – Finland’s great revivalist leader – had propounded. She did not stop preaching until she had turned seventy. Some of her sermons were taken down in shorthand and subsequently printed.

Many preachers did not speak in a state of ecstasy, but focused on promoting more profound spirituality within the church. Amelie von Braun (1812-1859) pursued social welfare work and ran a Sunday school in Karlshamn during the 1840s, but contemporary witnesses reported that many people came to hear her preach, either in her home town or elsewhere: “Is there anyone who believes that pastors and the male faithful objected when this woman began to perform their office? Is there anyone who believes that they disapproved of what she said? No, the dean and the assistant master and the neighbouring pastors and many schoolmasters stood there and listened attentively. Everyone learned something from this emissary of God, for she preached awesomely, and she strengthened and supported the church more than anybody else. Not to mention all the people who filled up the church green.” As suggested by the exegeses and discussions of theological questions that were written down, Braun appears to have been deeply committed to the spiritual condition of her age. A student in Uppsala wrote of her book, Christendomslifvet i vår tid (1860; Christianity in Our Time): “These notes are simply referred to as the book here, and were greedily read.”

Kirsten Larsdatter (“Forest Kirsten from Tårs”), was converted by the Mormons – who had won many Danish followers even in the face of strong resistance – as a young woman. However, she broke with them in 1851 under the influence of Grundtvigian pastors. She became a leading preacher throughout the North Jutland region and made a strong impression on her listeners.

The memoirs of Elsa Borg (1826-1909), the legendary leader of parish welfare work in Vita Bergen in Stockholm, recalls an incident during a youthful visit to vicar K. J. Svalander in Bringetofta in the province of Småland:

“Bringetofta attracted souls from near and far who were hungering for God’s grace […] On the weekends, those who had travelled long distances were invited to stay at the vicarage. One Sunday morning, the vicar went back and forth to the room and looked extremely upset. I asked him what the problem was. He said, ‘I just spoke with a woman from the poorhouse. She has unusual insight into God’s word. I’m so sorry that I can’t send her up to the pulpit to preach. She could do a much better job than I can’”.

“Readers” and Reading

Followers of revival movements were frequently called “readers”. Rising literacy and availability of Bibles enabled more people to study the Scriptures. Thus, even the unlearned could absorb and interpret the text. Bible societies, primarily from England, were organised in the Nordic countries to disseminate copies to the general public. Approximately a million Bibles were handed out in Denmark from 1855 to 1895. “What does the Bible say about it, and where?” was the question that seemed to be on everybody’s lips. Thanks to travelling lay preachers, many societies were able to spread inexpensive pamphlets to every class in remote areas of the country. Such activities were often linked to preaching and were an effective way of circumventing the restrictions of the Conventicle Act. While the literature tended to be newly written, often translated, older material found new readers as well. English and reformist piety made inroads, but the writings of Martin Luther were also more popular than ever. Particularly within evangelical revival movements of the early nineteenth century, women also started Bible societies of their own. Their purpose was to raise money for distribution of Bibles to the lower class, and they often recruited their members from the well-to-do. Such societies were regarded as effective means of eliciting and channelling women’s energy and desire to support an urgent cause. Making sure that Bibles were affordable and easily accessible was at the core of their activities, “and this responsibility is among those that lend dignity to the female character.”

Studying the Bible, as well as reading devotional literature and pamphlets, provided templates for living. Religious language supplied words to describe experience, expressions to help structure thoughts and ideas, even formulations for letters. The idiom could be used to underline solidarity and a sense of community, as well as aloofness towards the outside world. Letters and diaries that have been preserved provide a key to the vernacular that evolved in various religious groups. The pamphlets also became a source for the words and events that accompanied religious conversion, and many stories of spectacular spiritual experiences are strikingly stereotypical.

Maria Berg, or “Pali-Maja” (1784-1867), was one of the more interesting popular authors in Finland. Some of her many songs were written down and published in 1882. Distinguishing the religious from the non-religious writing of nineteenth century authors is often a meaningless exercise, given that the foundation of their language and worldview was in devotional literature. In honouring a bridal couple, Pali-Maja alludes to Jesus’s presence at a marriage at Cana as the template for a true wedding feast. Accused of being a pietist, she responded with a poem:

A sheep’s house, a shepherd then shall be / when the world from illusion unfettered is; / for the Master Himself has promised us this / to set all His flocks and His creatures free, /and save us from worry and squabbling and brawls /so the wolf no longer can threaten our lives.

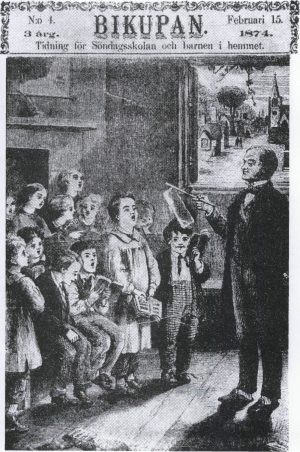

Revival movements were quick to enlist the press in the service of their proselytising. Pietisten (The Pietist), which began publication in 1842, is an important Swedish case in point.

Pietisten had a circulation of seven thousand copies in 1855. A daily newspaper like Aftonbladet, on the other hand, which was founded in 1830 by Lars Johan Hierta and served as the leading mouthpiece of Swedish liberalism until 1890, reached only four thousand people at the time.

Other periodicals, regardless of their circulation or how many years they survived, encouraged the growing interest in foreign cultures, as well as missionary work both at home and on distant continents. Statistics about missionary activities and the donations they received clearly demonstrate that trend. Special children’s newspapers were also published to supply the growing numbers of Sunday schools. The dissemination of all this new material had a major impact. Many people followed the newspapers, their articles were read out loud at meetings, and they were preserved by readers. They not only brought theological concepts and knowledge to broader swaths of the population, but spurred reading and conversation, created respect for familiarity with the written word, and promoted involvement in various social issues – not to mention all the new writers they fostered. Lina Sandell’s songs and stories were spread by newspapers like Budbäraren (The Messenger), calendars – her own Korsblomman (Flower of the Cross) and others – and brochures.

“Interpreting the Heart’s Joy in Triumphant Song”

“How many times have I not been part of the singing multitudes that walk to and from these meetings? Their beautiful and uplifting songs resonated in the still air.” Kirsten Dorothea Aagaard Hansen (1850-1902), a songwriter and translator, wrote the above words from Vikedal, Norway, where she grew up.

Songs played a major role in revival movements, particularly as a cohesive force and a means of expressing feeling or experience. The older canon satisfied much of that need in Denmark and Norway, and there was great resistance to the new hymnals that were published in the late eighteenth century.

Evangelisk-kristelig Psalmebog (The Evangelical Christian Hymnal) and other new hymnals faced heavy protest in Norway and Denmark. Nor were many hymns written in the spirit of Enlightenment theology. However, Dorothea Maria Moss (née Møller, 1777-1851) published Psalmer og religiøse Digt til huuslig Opbyggelse (1840; Hymns and Religious Poems for Domestic Edification). The book contains more than one hundred hymns and poems about God, virtue, reason, and immortality.

But many new hymns and spiritual songs were written during the century; particularly in Sweden, translations from English were very common. As a protest against the new hymns and their rationalist influences, Hauge compiled a hymnal in 1799 that included his own contributions. Aarflot was not the only female Haugian who wrote spiritual songs. Hauge’s Christendommens Lærdoms-Grunde (1804; The Basis of Christian Doctrine) also contained songs written by his followers, including Larine Olsdatter Øxne, Pernille Hansdatter Bru, Kristi Kristensdatter Marken, and Christi Olsdatter Nyre.

Some statistics to illustrate the extend of activities of the Methodist Church, which has its roots in the United Kingdom, the home of the Sunday scool: In 1869, the Church had 1326 members and 921 children in Sunday school in Sweden. By 1876, the membership had swelled to 5663, and 5000 children were enrolled in Sunday school.

Haugian hymn writing reflected the need for an indigenous Norwegian culture that arose after 1814. De Troendes daglige Omgång med Gud (Believers’ Daily Communion with God) by Berthe J. Barstad was published in Bergen in 1847.

Many hymnists outside of the Haugian movement also deserve mention. Gustava Blom Kielland (1800-1889) began writing hymns at an early age, and translated from German into Norwegian as well. Erindringer fra mit Liv (Memories of My Life), which she wrote at the age of eighty-two, is a lively depiction of life at a parsonage in the early nineteenth century. Clara Ahnfelt (1819-1896) was married to Oscar Ahnfelt, a well-known singer and travelling preacher. He set poems from Pietisten to music, and he both sang and preached on his long tours of Sweden, Denmark, and Norway. The couple belonged to the circle around Carl Olof Rosenius (1816-1868), a leading Swedish lay preacher of the new evangelism. Their home in Karlshamn became a spiritual centre after they moved from Stockholm in 1851. While he was gone for months on end, she took over management responsibilities and helped run sewing circles and a Sunday school. Sewing circles often served as auxiliaries to missionary activities in Sweden and other countries or as committees for the relief of social hardship in the local community. Ahnfelt also wrote a number of songs that her husband set to music, and she translated Hans Adolph Brorson’s hymn “O Helligaand, mit hjerte” (“Oh Holy Spirit, My Heart”) and added several verses.

Carolina Almqvist (1829-1861), who was born to a poor couple in the Swedish province of Dalsland, left home at the age of fourteen to work as a maidservant. Pilgrimsharpan (1861; The Pilgrim’s Harp) contains eleven songs for which she wrote both the words and music.

Perhaps because the work of pastor and poet Nikolaj Frederik Severin Grundtvig (1783-1872) so fully satisfied the need, few Danish women wrote hymns in the nineteenth century. However, Indre Missions Sangbog (1910; Inner Mission’s Songbook) includes fifteen songs by Emilie Thorup (1857-1890). A number of sermons and other reflections, which she had not shown to anyone, were found in her drawers after her death. Her spiritual songs, some of which had been published anonymously in a magazine, were brought out under the title of Efterladte aandelige Digte af E. (1891; Posthumous Spiritual Poems by E.). Alberta Eltholtz (1846-1934), a nurse and writer, made a number of contributions to Metodistkyrkans sångbok (1876; The Methodist Church’s Songbook), which was published in Denmark.

Happily We Go to Sunday School, to Pray and Sing and Listen

Religious life began to take on new forms in response to the social transformations of the nineteenth century. In the old agrarian society, children received their spiritual education in the home, formally the responsibility of the husband but often run by older female members of the household. Sunday schools, particularly in the growing cities and other densely populated areas, sprang up to meet the need for a whole new kind of Christian instruction. Mathilda Foy (1813-1869) and Betty Ehrenborg-Posse (1818-1880) were members of the Rosenius clique. After obtaining both inspiration and knowledge on a visit to England, they launched Sunday schools in Stockholm during the 1840s and 1850s. Ehrenborg-Posse also began to offer courses for future teachers. Although she was highly sceptical of any departure from Lutheran doctrine, most participants are said to have been “Baptists and Separatists.” Bibel-Wännen (Friend of the Bible), Missions-Tidning (The Mission Paper, and other newspapers spread information about Sunday schools and spurred similar activities in other places. Maria Nilsdotter, “Mor i Vall”, in Karlskoga read about Ehrenborg-Posse’s projects in Stockholm and resolved to start the first Sunday school in the province of Värmland. Nilsdotter wrote to Ehrenborg-Posse, who offered both advice and a number of teachers. She expanded her activities to include an orphanage in 1858 and a weekday school later on.

Sunday schools were a highly effective means of introducing children to revivalist thinking, and singing played a big part. The need arose for new literature, devotional songs, and reading material for training and education. Special newspapers and pamphlets for children were published. As the editor of Barnens Tidning (The Children’s Newspaper) and Barnens Vän (Children’s Friend), Lina Sandell had a great deal of influence on what happened in the Sunday schools. Like Ehrenborg-Posse, she composed a number of songs and stories for that purpose. Matilda Foy wrote and translated stories in Christelig månadsskrift för barn (Christian Monthly for Children) in 1860 and 1861. While some of them might seem overly moralistic to the modern world, others offer revealing descriptions of everyday life and present interesting characters. Women are portrayed as taking the initiative to relieve the hardships of poor children, and a lot of knowledge about history and geography is conveyed. The preoccupation with general education that was so widespread at the time is evident here as well.

The contributors were many, particularly after the mid-nineteenth century when the various revival movements were organised in intra-church associations or Free Church societies, and Sunday schools had become common in the State Church as well. Marie Wexelsen (1832-1911), a Norwegian, was still young when she started writing songs and stories for children. Heavily influenced by Grundtvigianism, she had attended Askov Folk High School and developed an interest in children and folk high school instruction. She was also one of many revivalists in the burgeoning women’s emancipation movement. Laura Margrethe Trojel of Denmark contributed to Kristeligt Børneblad (Christian Children’s Newspaper) in the 1870s. Lilly Lundequist (1847-1925) and Emilia Ahnfelt-Laurin (1832-1894) wrote and translated in Sweden. Ahnfelt-Laurin translated over a hundred of Grundtvig’s hymns into Swedish, as well as her uncle Oscar Ahnfelt’s collection of songs into Norwegian. Elevine Heede (1820-1883) was associated with the Methodist Church’s publishing house in Christiania (Oslo) until 1874.

Grundtvig’s poems often depict the Dannekvinde (good woman and true) as a bearer of culture, language, history, and literature from one generation to the next. His portraits of soft spoken, dignified, and maternal figures influenced many teachers and other women who wrote prose and poetry, as well as the circle around the Danish Women’s Society, which was founded in 1871. While Grundtvig linked his concept with that of the enlightened peasantry, these writers were more interested in turning their middle-class sisters into Dannekvinder.

She translated most of the books that they brought out and edited Børnenes Søndagsblad (Children’s Sunday Newspaper). Although she wrote her own material, her speciality was translation of spiritual songs. Her ability to combine originality and fidelity to the original won great admiration and ensured that the hymns are still sung today.

The Good Woman and True Blossoms in Denmark

The growing interest in general education during the nineteenth century heavily affected Christian movements, not only among children. Grundtvig felt called upon to awaken the people to genuine, living Christianity. After visiting England around 1830, he wrote a number of articles that fleshed out the idea of starting a school in Sorø for young people from all social classes. His goal was to instil in them a greater understanding of the human condition, which he regarded as divine, awesome, and marvellous, and prepare them for their place in society. History and poetry would be the most important subjects in this School of Life. The folk high schools that emerged around the country drew most of their students from the peasantry.

Women were also needed if the educational level of the rural population was to be raised and the nation strengthened. As of the late 1860s, folk high school courses were available to women during the summer, an opportunity that they increasingly took advantage of. The courses made a major contribution to the public debate about women’s role in society and marriage. Like the growing number of community organisations, they provided many young women with the identity, training, and confidence they needed to express their opinions on political and social issues. Folk high school instruction stressed development of an individual’s skills and opportunities, acknowledging the right of women to have interests of their own without undermining the institution of marriage.

Henriette Skram chronicled the work of her teacher Nathalie Zahle, arguing that her importance “for Danish schools was that she staunchly channelled the Grundtvigian current in the right direction instead of allowing herself to be washed away by it […].” That she never abandoned the “[…] foundation of order and obedience.”

For part of 1852, Grundtvig’s home was a sanctuary for Mathilde Fibiger, who had aroused controversy and condemnation with her novel of emancipation Clara Raphael: Tolv Breve (1851; Clara Raphael: Twelve Letters). She never became a Grundtvigian, even though her ideas about women’s national and cultural responsibilities bore similarities with his notion of the Dannekvinde. Pauline Worm, a teacher and author who took part in the debate about Fibiger’s book, was a Grundtvigian convert. Similarly, Nathalie Zahle assigned great importance to his educational concepts in her efforts to reform Danish schools for girls.

The memoirs – written in 1876 – of Henriette Lund, the young niece of Søren Kierkegaard, described her experience of Grundtvig and the services at the Vartov church:

“I was so taken by the lively hymns that were so uncommon at the time, as well as the intimate atmosphere, that I continued to attend, and had to smile back when I ran into Uncle Søren, who slyly remarked, ‘You’ve got to watch out for these Vartov influences.’ Mum was just as enamoured of that movement.” –

Erindringer fra Hjemmet (1909; Recollections of Home).

Grundtvig’s ideas about Christian life, “the living Word”, and popular education were democratically oriented and helped breed the peasant movements of the late nineteenth century. In 1839-1872 he served as a pastor at Vartov, to where many students, future clergy, and folk high school teachers came to hear his sermons. Many of his listeners subsequently promoted an active, new congregational life as pastors. As a result, Free Church congregations were not as common in Denmark as in Sweden, while the social geographies of the two countries differ significantly. The Church Association for the Inner Mission in Denmark, which was formed in 1861 for the express purpose of “bringing prodigal sons back to the house of their Father”, also contributed to those trends. Travelling lay preachers, particularly Vilhelm Bech – the association’s leader for forty years – put lay revivalists throughout rural Denmark in touch with each other. Sermons by Inner Mission preachers, who emphasised penance and conversion, were more in line with traditional revivalism than with Grundtvigianism, and violent and dramatic confrontations between the two groups were not unheard of.

People became more mobile as the years went by, and it wasn’t unusual to travel many miles by foot to listen to a good preacher. Although parsonages would often serve as spiritual centres, new religious currents rippled out from one district to another without the mediation of the upper class. Jacob Nyvall wrote that his father was annoyed by the “newfangled fancies” of his wife Maria Nillsdotter – who became known as “Mor i Vall” (Mother in Vall) – and tried to stop her from “running to the pastor”. His solution was to tie her to the kitchen with a rope, long enough so that she could continue to perform her chores.

“Beloved Friends of Christ. May God’s Mercy and Peace Be upon You.”

Both early revival movements and the Free Churches of the late nineteenth century are often portrayed as harbouring a degree of antipathy to culture. This has something to be said for it if culture is limited to that which is official and generally accepted. Adherents of these movements wrote and consumed literature, albeit of a different type. While somewhat sceptical of fiction and the like, they freely cultivated other genres. As literacy and interest in the written word spread, letter writing as a form of literature took on great significance among Norwegian Haugians. Their extensive correspondence reflected not only devotion to spiritual questions, but the ever more popular idea of recording thoughts and anecdotes from daily life. The letters are fascinating and valuable historical documents. Many of Aarflot’s letters were printed in En Samling af religiøse Opmuntrings- og Opbyggelsebreve (1844; A Collection of Religious Letters of Encouragement and Edification) and other publications.

As is often the case with literary genres, specific antecedents shape both form and content. Traces of Hauge’s autobiography and the story of his conversion can certainly be found in the letters that his followers wrote to each other later on. The countless epistles also reveal the existence of a common template with respect to handwriting.

Fictional accounts were criticised as mendacious and make-believe. But the literary impulse found other outlets, such as documenting and chronicling real-life events. Nordic Churches and missionary societies dispatched their own missionaries in response to growing demand for their services in the nineteenth century

Anna Johansdotter Norbäck led a revival movement in the Swedish province of Ångermanland from the 1830s until her death in 1878. Based on her readings of Luther and the Bible, she opposed certain aspects of the church’s instruction and liturgy. As a result, she started her own congregation with a separate Communion.

– not only within their own countries, Lapland, and Greenland, but to the far corners of the Earth. Female missionaries were needed as nurses and teachers of women in foreign cultures. Letters, diaries, and travelogues – whether buried in the archives of the various missions or published in their newspapers – offer abundant insight into their lives and work.

Aarflot is a recurring figure in the history of Haugianism and Norwegian hymn writing. Nicolava Nilsdotter (?-1896), “Moster i Klerke” (Aunt in Klerke), is one example out of many who maintained a lower profile. She put up lay preachers who came to the parish. She called the faithful of the district together, read them the word of God, and offered edifying sermons. Moreover, she taught Sunday school and started a little sewing circle, whose collections were donated to missionary activities. She also took the initiative to form a Free Church congregation in Klerke.

Translated by Ken Schubert