The new women’s movement quickly spread throughout the Western world together with the youth and student movements. An English conference in 1970 sparked the start of Women’s Liberation, where young, well-educated women banded together in movements that differed significantly from and broke ties with traditional women’s political associations. The new women’s movement was anti-hierarchical and crossed boundaries. It eradicated the difference between the political, the cultural, and the private. The new movement did not become a political party but a forum of groups that brought the battle of the sexes into the family, out to the media, and onto the streets. Women wanted economic equality and new views on body, sexuality, reproduction, and the division of labour at every level of society. Women wanted to create a new culture that broke ties with conservative, male society, not only in its content but also in its form and organisation.

In the Netherlands they were called Dolle Minaer. And the Redstockings from New York gave birth to the Danish name Rødstrømper. In Norway, the New Feminists formed in the autumn of 1970; in Sweden, Grupp 8 formed in 1968; and in that same year in Iceland a youth group, Úur, formed under the women’s rights association. In Finland there was no distinct women’s lib association, but Forening 9 (1965-73) played a role in the equal rights debate.

The 1960s was the decade of the gender role debate. Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique (1963) addressed the traditionalisation of American family life in the 1950s, and before that, in 1949, Simone de Beauvoir published her major controversial work Le deuxième sexe (Eng. tr. The Second Sex), which claimed that women are not born but made. The new female consciousness grew out of an increase in prosperity in the middle layers of society and a higher level of education among young women. However, the youth revolt and upheaval on the political left, from the marches against nuclear armament and the anti-Vietnam movement to 1968 and the university protests, especially the May protests in France, became a symbol of the fight against privilege and conservative power. Women shared with the student protests a resistance to authority and an indignation at global injustice; however, in the student rebellion they also found a limit to justice and equality, a limit that drew a line at gender and the so-called private sphere.

New Scenes

In the new movements, women began looking inwards at themselves and each other as well as outwards to the general public. Inwardly, they organised into consciousness-raising groups, shared experiences, sang, danced, and took courses in self-defence or self-help and self-examination. Outwardly, actions and demonstrations were the preferred method of making women visible and of being heard, as they had become internally, to each other. In Denmark, a demonstration along the pedestrian shopping street Strøget, in the heart of Copenhagen, where the protesters wore balloon breasts and oversized eyelashes, marked the start of a new era. And it was characteristic of the movement’s double vision that the demonstration against fashion’s views of women was effortlessly followed up by an action for equal pay: the utopian movement was all-embracing. In its mode of expression, it was a grotesque, humorous show combined with a constant insistence that they be taken seriously. Under the motto “Keep Denmark Clean” women burned their bras in the Town Hall Square, thereby interpreting femininity as theatre while at the same time marching onto the stage with their own texts, costumes, and decorations.

The women’s movement created its own space, first and foremost a number of “women’s homes”, which were established all over Denmark. The women’s homes served as bases for the consciousness-raising groups and their subsequent organisation. From 1974, women gathered at an annual women’s festival in the People’s Park in Copenhagen, but as early as 1971, the women’s libbers took over the Danish island of Femø with a summer camp that has been a recurring annual event ever since. The camp and the women’s homes represented a special space for women, refuges from male society, sparking a debate in the media about the justification of a space where men are forbidden access. A women’s culture developed that differed from the rest of the world, but which also produced a number of the manifestations that made their way into the world.

The Femø camp was organised as a kind of ideal vision of the women’s movement:

“In the morning, the residents of each tent held a tent meeting. After lunch there were groups for specific things. Some groups met regularly, like the theatre group, the yoga group, and the self-defence group. Other meetings were called whenever we discovered that someone knew something which would be educational for everyone, like prevention, abortion, educational opportunities for older women, women’s movements in other countries. In the evenings we held community meetings for everyone and then there was festivity and dancing in the ‘pub tent’, which was spontaneously organised by a group during the second week.”

Jordemorpjecen (1976; The Midwife Leaflet)

The fight for the right to abortion took centre stage for women’s movements throughout the Western world. In some countries, like Italy, abortion was the most important item on the movement’s agenda as the ultimate symbol of women’s sexual self-determination and right to decide over their own bodies. In the private sphere, in the homes and consciousness-raising groups, the theme was women taking back their own bodies and sexuality. Whereas the morality debate of the 1880s was about women’s right to define their own sexuality and the debates of the inter-war period focused on voluntary motherhood, in the 1970s women fought on both fronts, and in self-examination groups the battle became extremely concrete.

With a speculum women could see their own vaginas, which were no longer reserved solely for men’s eyes and penises. With cropped hair and stripped of fashion accessories and makeup, they stepped out as a gender that was not a product of the fashion or pornography industry. And with the birth control pill, free abortion, and the limited risk of sexually transmitted diseases, women had, for the first time, access to a sex life that was not associated with fear of contagion, pregnancy, and death.

In Denmark, the youth section broke ties with Dansk Kvindesamfund (Danish Women’s Society) in 1966 over the issue of abortion rights and the practice of travelling to Poland to get an abortion, which the young people organised. In France, Simone de Beauvoir and Brigitte Bardot, together with 341 other famous women, admitted that they had had an illegal abortion. Abortion was legalised in Denmark in 1973, in Norway and Sweden in 1975.

The Song, the Fight, the Laughter …

On Femø – and on the road to and from the island – women wrote and sang songs that bore witness to the intoxication and powerful feelings that the women’s community nurtured. “Written in the car on the way home from the first visit to Femø 22 May 1971” it says beneath the lyrics of the Danish hit song “Du må få min kasserolle” (You Can Have my Saucepan), where the fourteenth and final verse says: “But don’t feel safe when I leave. / I’m off to women’s camp / to prepare for victory. / But don’t feel safe when I leave”. Kvindesange (1974; Women’s Song). The melodies could be new, but the most popular were new texts to old political anthems and folk songs that greeted the old texts with irony, such as the socialist song “Internationale” (The Internationale), which became “Søstersolidaritet” (1970-71; Sister Solidarity) and was given a new and rather concrete refrain: “sister solidarity / unites from breast to breast” (Kvindesange). Like most of the writings from the official women’s lib movement, the songs were anonymous, symbolising that the actual source of the flyers, magazines, and poems was the women’s community in general. The album Kvinder i Danmark (1975; Women in Denmark), which a reviewer for a local Danish newspaper, Aarhus Stiftstidende, said was produced by “an indeterminate number of nameless women”, featured the same genres, from ironic imitations of pop songs – “Kaj, do you want me” – through social-realist ballads to collective battle songs.

“Liberation is near, the time is ripe,” sang the women in Jösses flickor (1974; Gee Girls). This song, like several others by Suzanne Osten and Margareta Garpe, became part of the women’s communal treasury of songs. “Say something to me / say something to me and I will turn around,” sang the Danish Trille, whose album Hej søster (1975; Hi Sister) became embedded in Scandinavian women’s hearts.

In Sweden, too, the women goaded the men, writing their own “counter-history” as in Louise Waldén’s “Historisk Tango” (Historical Tango), where the refrain repeatedly asks: “What did women do while men made history?” The answers range from taking care of his children to polishing his halo. This audacious and humorous song was sung into the hearts of Swedish women by the feminist rock band Röda Bönor (a pun in Swedish meaning both “red beans” and “red chicks”). They also wrote many of their own ballads that struck a chord. Kjerstin Norén’s parody of the old hit “Oh, oh, oh, what have you done to me?” in “Sangen om kvinnans otäcka roller” (Song about Women’s Disgusting Roles) was one of the most popular. Together with a number of Swedish songwriters, artists, and writers, including Marie-Louise Ekman, Annbritt Ryde, and Elisabeth Hermodsson, in the 70s they created feminist pop and rock music that quickly found favour in the media through, among other sources, the radio music programme Spinnrock.

Images of Revolt

In the 1970s, the women’s movement captured the media. With plays like Man råkar vara kvinna (1970; One Happens to be Woman) and TV series such as Fosterbarn (1971; Foster Child), Dela lika (1972; Share Equally), Klassträffen (1975; Class Reunion), and Lära för livet (Learn for Life), Carin Mannheime, “the most liberated girl on TV”, brought social involvement and the feminist protest movement into Swedish homes during prime time. Britt Edwall, radio employee, director, and author, created biting and provocative radio drama for a new generation of women. Suzanne Osten and Margareta Garpe renewed theatre’s means of expression with one powerful performance after another. The large state art museums featured a series of exhibitions focusing on women, and attracting a great deal of attention.

In the 1970s, a strong new generation of women critics appeared on the cultural editorial boards and in the opinion pages of the Swedish newspapers. Eva Moberg promoted women’s rights in the social discourse in the Swedish daily Dagens Nyheter, where feminist literary critics, such as Eva Adolfsson and Maria Bergom-Larsson, also had a major influence with their leftist criticism. Monica Boëthius opened the door to women journalists in the consumer cooperation’s weekly newspaperVi. In the major daily Aftonbladet, Agneta Pleijel was made culture editor while Åsa Moberg attacked male and class society, and journalists such as Annette Kullberg rejuvenated journalism with their provocative reporting.

In 1975, the United Nations International Women’s Year, the major exhibition Kvinnfolk (Womenfolk) was exhibited in both Stockholm and Malmo. The mixture of documentary and art, contemporaneity and history, interviews and poetry attracted huge numbers of women who wanted to see and discuss the exhibits. The exhibition Livegen – eget liv (Serf – A Life of One’s Own) in Gothenburg in 1973 was its predecessor, and the brilliant follow-up was Vi arbetar för livet (We Work for Life) in Stockholm in the autumn of 1980. The exhibition featured a series of “women’s rooms” created by a number of women artists, and visitors walked through images and counter-images, past an artificial uterus, met Lilian Ek’s drawing “satans kællinger” (Damned Bitches) and Gittan Jönsson’s “Prinsessan panic” (Princess Panic) – laughter mixed with tears, seriousness and anger with good spirits.

“For too long, we have been so underestimated that no one – not even ourselves – has appreciated what women have created,” wrote the collective behind Kvinnfolk in the exhibition catalogue, which sought to communicate images and counter-images from history and contemporary society. “When Anna Sjödahl, who has four children, paints motherly love, she does not create sparkling, Madonna images, but the mother’s bleeding heart being torn apart by all the conflicting demands, by inadequacy in the attempt to live up to the impossible task that is imposed on women: sole responsibility for the future generation,” they wrote. And young artists like Anna Sjödahl, Monica Sjöö, Lena Cronqvist, and Rauni Liukki were given the opportunity to present a view of women that differed from the societal clichés.

We are the new women

We are the new women who

have been educated

Now we will re-establish ties

with the working class, our

mothers

We are the new women,

the historyless women.

So begins Anna-Lisa Bäckman’s poem “Manifest” on the back cover of the exhibition catalogue for Kvinnfolk (Womenfolk) in Stockholm, 1975. The poem ends on a rather triumphant note:

We are the new women

We are here now

Now we will recognise the old

as our first history

and we will never

emulate them.

In the theatre, the traditional male-dominated society and its views of women were attacked in new, burlesque ways. “Oh, oh, oh girls! We must raise our voices to be heard,” the young women sang in the final scene of Suzanne Osten’s and Margareta Garpe’s youth play Tjejsnack (1971; Girl’s Talk). It was a small, touring theatre performance for young audiences, but the songs spread like wildfire throughout Sweden and all of Scandinavia, quickly becoming part of the common (political and passionate) collection of songs, slogans, treatises, and theories that tied the new women’s movement together across borders and continents.

Two years later, in Kärleksföreställningen (1973; Love Performance), male-dominated society, with its stunted and distorted view of male and female sexuality, was stripped to the bone. In a burlesque approach that made a serious break from the conventional illusion-aesthetics of Swedish theatre, Suzanne Osten and Margareta Garpe trounced the powers that deny women the right to love by exploiting and violating their sexuality. In hilarious and almost carnivalesque ways, they personified the indignation, anger, and criticism, and had audiences shouting with joy.

When Suzanne Osten and Margareta Garpe’sKärleksföreställningen(1973; Love Performance) was broadcast on Swedish television in 1975, Leif Silbersky, a lawyer and one of the legal representatives of the liberalisation of pornography, sued them for “slander and defamation”, but the claim was dismissed.

In the successful play Jösses flickor (1974; Gee Girls), the women’s association that gave its name to the play did not experience much growth in the time period in which the play is set – 1924-74 – and yet it is still an homage to the power of women. And even though Suzanne Osten and Margareta Garpe both here and later recount tales of women’s powerlessness, it is not their failures that are important, but rather the criticism of society that unvaryingly exploits, inhibits, and divides them, and there is never any doubt that women are now in the process of creating something radically different.

Carnival and the Battle of the Sexes

“We believe women’s culture can be an important support for the women fighting dismissals and layoffs in their workplaces – for those manning stands and gathering signatures for the right to abortion, and for those discussing women’s issues in workplaces and at schools,” wrote the Norwegian song group Amtmandens Døttre (The District Governor’s Daughters) in the programme for their album Reis kjerringa! (1975; Pull Yourselves Together Ladies).

The title of the album and the programme declaration are symptomatic of the integration of class struggle, feminism, and art in the 1970s. Personal experiences, questions about identity and body, were primarily viewed as political themes. The private is political, as they said in the women’s movement and with regard to sexual politics on the political left; the body, the emotions, and the sexes were now a public issue and became a political theme. Politicisation was the 70s version of a world view, and for women it allowed them to view all of womanhood as part of societal life and thereby take women’s life out of a natural history context and tradition and move it into the changeability of modernity.

In the new women’s culture, it also became politically important to give women the courage to express themselves in public and utilise their talents, resulting in the removal of the distinction between amateur and professional, between “high” literature and “low” literature.

Toril Brekke, together with Amtmandens Døttre, wrote the text for “Smedevise anno 1974” (Song of Scorn of 1974), which struck an entirely different chord than literary poetry. With carnival-like methods, the ballad dethrones a man, the Norwegian Minister for Finance Per Kleppe, who represents the patriarchy, Norwegian social democratic politics, and international Big Business. The ballad builds on textual references (the children’s story about Karius and Baktus, the play Peer Gynt, various popular songs and traditions like Father Christmas) which are recognised by everyone, creating a new partly ironic text that is thus both direct and indirect criticism.

See there he is again

Mr Minister of Finance

whose mild and handsome voice

says nice words

about the thousands of new jobs

for our womenfolk

for our womenfolk.

All sorrows recede

When Kleppe opens his sack.

Kind Kleppe Claus,

no one can go on like him

about the great oil adventure’s

gift to our country.

If the Minister keeps his word

they will have work where they live,

all the women home alone

at the kitchen sinks.

The Labour Party will finally

show what they can do.

Per you’re lying, we see it now.

Lovely sugar-coated lies.

Not concerned about the people’s welfare,

but about Texaco and Shell.

Like all Labour ministers

you are always capital’s man.

“Smedevise anno 1974” (Song of Scorn of 1974)

Else Michelet (born 1942) uses the same technique of reversal in her texts, where she demonstrates how oppressive modes of understanding are invisibly written into language and stories. In her book Sin egen herre (1979; One’s Own Master), she takes as her point of departure old and new myths and fairy tales, writing new stories with a feminine influence. “Three Billy Goats Gruff” becomes “The Three Misses Madam” and “La Dame aux camélias” becomes “The Camel Lady”. Man – from Adam to Tarzan – is dethroned in cheerful, biting black humour. The book En annen historie (1981; Another History) interprets history from the point of view of a woman. In short stories, diary entries, poems, and discussion papers, our entire patriarchal culture is put on the agenda – always with a critical, humorous, and offensive attitude.

A text like “Smedevise anno 1974” is firmly placed in a tradition of collective women’s struggle poetry and culture of ridicule, and is a good example of how the radical feminism of the 1970s drew on the cultural traditions and political understanding of socialism and the labour movement, while at the same time rebelliously undermining the pathos of the tradition. The political and didactic point of departure was striking in a play about women in low-wage jobs who worked twice as hard, which in 1972 had its premiere at the National Theatre in Oslo. Jenteloven (The Law for Girls),

“Friends, THIS is a movie you must see. It has finally brought blessed humour to the serious women’s lib movement. I haven’t enjoyed myself so much in ages as when I and Nadja saw Ta’ det som en mand, frue!“ (Eng. tr. Take it Like a Man, Ma’am!). Tove Ditlevsen in the Danish daily Politiken, 13 April 1975

the result of a group effort by, among others, Liv Køltzow and the director Anja Breien (born 1940), tells the story of women’s lives in families and at work, and constructively proposes solutions, including new laws for women in the workplace.

With To akter for fem kvinner, (1974; Eng. tr. Two Acts for Five Women), Bjørg Vik entered the Nordic and the international women’s scene. After the premiere at the National Theatre in Oslo, the play was performed in Bergen and Stavanger, and as a television play. Later, it also ran in Denmark, Sweden, Iceland, Germany, Austria, and the USA.

Margaret Johansen also achieved a solid breakthrough with her play Du kan da ikke bare gå (1982; You Can’t Just Leave). Based on a novel from 1974, it addresses the theme of marital violence, making the battle of the sexes extremely concrete. The play was performed in several cities, but is best known as a television play. It also represented Norway at the first Nordic Theatre Festival (Oslo, 1984).

While women’s theatre flourished, there were not nearly as many new films created by women. The medium was more expensive and there was a lack of women with the right technical training. In Denmark, a large number of workshop films were produced, partly as documentation of the women’s movement and women’s lib and partly as aesthetic, experimental films about the inner thoughts of women. The full-length film Ta’ det som en mand, frue! (1975; Eng. tr. Take it Like a Man, Ma’am!), by Mette Knudsen, Li Vilstrup, and Elisabeth Rygård, uses satire as a means of revealing the power struggles between the sexes. Everything is turned on its head when the film’s fifty-year-old housewife dreams about another world where, as the female head of a company, she can surround herself with young, well-dressed office men.

Femø 1971 and 1. maj 1972 are examples of documentary films created by women; however, women artists also experimented with symbolic films, such as Tre piger og en gris (1972; Three Girls and a Pig) by Ursula Reuter Christiansen, Elisabeth Therkelsen, Lene Adler Petersen, and Per Kirkeby, and Jytte Rex and Kirsten Justesen’s Tornerose var et vakkert barn (1971; Sleeping Beauty Was a Handsome Child).

Anja Breien’s Norwegian film Hustruer (1975; Eng tr. Wives) occupies a realistic narrative tradition with the story of three friends who meet at a class reunion fifteen years after graduating from secondary school. After the party they decide to stay a little longer, taking a break from daily life and extending the party. Together they go to a café, to a public bath, to a bar, and take the ferry to Denmark. The movie thematises their frustrations, but their energy and their sister solidarity also become key factors in their attempts to grapple with daily life and the future – a point that is emphasised even more clearly in the sequels Hustruer 2 (1985; Eng. tr. Wives – Ten Years After) and Hustruer 3 (1996; Eng. tr. Wives III).

Liberation is near

the time is ripe

We women are waking up.

Oh, dear sisters

the day is finally here

when we support each other

to take the giant leap

to pass our final test

up to the bread and roses

to each according to need

But can we? Will we? Dare we?

Yes, we can! We will! We dare!

Yes, we can! We will! We dare!

Yes, we can! We will! We dare!

And one day, the children will say

thanks mothers, you’ve done well

yes, one day, the children will say

this human world is something we want.

Jösses flickor (1974; Gee Girls)

Experience and Utopia

The Wives films were not only an expression of a woman’s view of the world, they were also a response to the need to see, hear, and read about women’s lives, to document and identify with other women’s experiences. For generations, women had been the readers, the most important audience for fiction; now they were looking for new female heroes. Erica Jong’s Fear of Flying (1973)about Isadora Wing who dreams about “the zipless fuck” became a cult classic. Even before it was translated from English, Suzanne Brøgger’s enthusiastic review spread across Scandinavia. “She has,” Brøgger wrote about Jong, “introduced a whole new type of woman.” However, interest in the “average” woman and her experiences was, if possible, even greater. The 1970s was the decade of documentary and reports, and in book after book, women told the stories of the lives that once had been considered hopelessly unliterary. It was as though the market could not get enough of the stories that had previously been repressed. As early as in 1969, Carin Mannheimer published Rapport om kvinnor (Report on Women), in which twenty-eight women tell their life stories. In Nio kvinnor nio liv (1977; Nine Women Nine Lives), the local Stockholm’s Grupp 8 group, Aurora, tell about their daily lives. De bara e’så (1978; That’s Just the Way It Is) is the name of Barbro Myrberg’s narrative on the most average days in her life. In Snittet (1979; Caesarean), the midwife Marja-Liisa Abrahamsson criticises Swedish birth ‘care’ by reporting on her own C-section.

“If we shared our secrets, we would discover that they are often the same, and we would be able to talk about the difficulties and take up the struggle to overcome them,” writes Agneta Klingspor in the printed version of her diary Inte skära bara rispa (1977; No Cuts Just Scrapes). Opening the door to the secrets of private life was more than just a political strategy in the consciousness-raising groups of the women’s movement, where the members told their life stories to each other; it was also a very prolific literary strategy.

In the countless documentary books and reports that came out of the Danish women’s movement and the surrounding environment, the objective was especially to show women’s lives as they really were – in the factory, in the home, in prison, in political life, or in women’s inner lives, as was demonstrated by the so-called “out of the drawer” movement, which focused on the publication of women’s poetry and texts in such works as Poesibogen (1974; The Poetry Book). The first Danish contribution to the so-called report genre was Suzanne Giese’s and Tine Schmedes’ Hun (1970; She), which alternates between interviews and fictitious accounts. In 1972, Jytte Rex published Kvindernes bog (The Women’s Book) with fifty-six subjective women’s histories that sparked a debate on the relationship between experience and theory.

Experience, politics, and theory were also intertwined in the new journals that arose after the women’s movement, in the early years, “took over” a number of established journals with themed issues edited by women’s collectives. In Norway Sirene (1973-83), KjerringRåd (1975-85), and Kvinnefront (1975-83) were forums for feminist debate and literary criticism. In their pages, practitioners and theoreticians met to discuss the goals and tools for feminist art, and many contributors got their feet wet for the first time as critics. In 1983, a new journal of feminist literary criticism was established. Kritikkjournalen quickly became the leading journal of literary criticism in Norway, and in 1994 it published its first pan-Nordic issue.

In Sweden, the leftist, socialist journal Vi människor became a forum for the new women’s movement, and in an old, well-established cultural publication like Ord & Bild the women’s perspective suddenly began to dominate. The movement even got its own dedicated journal with Grupp 8’s Kvinnobulletinen (1971-96), and 1980 saw the start of the academic journal Kvinnovetenskaplig tidskrift.

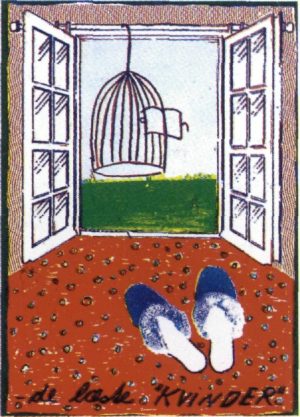

The United Nations International Women’s Year, 1975, saw the launch of the Danish magazine Kvinder, which sought to be an alternative to traditional women’s magazines. It was printed on glossy paper and in colour, but with a collage-like layout that contrasted sharply with the sleek naturalism of the weekly magazines. Politically as well as aesthetically, it was an attempt to create a women’s political counter-culture. One themed issue on breast cancer (no. 12/1977) features a cover photograph of a woman wearing only underpants and a straw hat that hides her face. She is sitting cross-legged with her hands in front of her privates, with her upper body completely bare: she has only one breast. The cover page, which is toned in turquoise, appears to be a matter-of-fact photo of a woman’s body that does not conform to the ideals of fashion, but with props like the hat and the toning, the photo breaks with naturalism. We see femininity as a masquerade as well as the true nature of femininity.

Kvinder never outsold the weekly magazines, but the women’s movement, with its utopian demand for “Umwertung aller Werte” (transvaluation of all values) was still the greatest event of the century in every aspect of public life: the private, the political, and the artistic.

The Norwegian title is a word play on the Jante Law – Janteloven – an alleged pattern of social behaviour in the Nordic countries which serves to cast individual success and achievement as suspect and worthy of criticism, placing all emphasis on the collective.

Translated by Jenifer Lloyd