The 1930s celebrate the body in all its aspects; it becomes a symbol of the health and naturalness of a new age – and it does so in keen competition across the whole political spectrum. In this context, the leading Danish cultural radical Poul Henningsen (1894-1967) pays tribute to the African-American dancer Josephine Baker for her minimal outfits, while the healthy, young body of the Nazi agenda is paid homage in Leni Riefenstahl’s filming of the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin. And, above all, it is the female body as aesthetic object and as birth-giving organism that is simultaneously elevated, excluded, and subjected to the law of progress.

The entire political, cultural, and literary development is involved in the battle to draw boundaries for culture and politics, to characterisez against what these fields of activity define themselves. And therefore the women’s texts are not merely comments on and thoughts about women’s circumstances, and the form of the texts is not merely expression of a tradition or a new departure; the texts infiltrate and change literary paradigms in the campaign both to define the nature of a woman’s body and desire, and to define how modern literature and a modern democracy should be read.

“In recent years, first here and there and then throughout Germany, workcamps for women were set up – and were immediately embraced by young women. Many of them came straight from the typewriter, others came from the shop counter, and yet others left the factory to join in the fresh and healthy outdoor work, and as can be seen from our photographs, taken in a workcamp on the moor, none of these young women look sad or cowed. On the contrary, they are all radiant with health, happiness, and high spirits. For it is a fact that women are quite excellently suited to manual outdoor work.”

“Fra Skrivemaskinen til Ryddehakken” (From Typewriter to Mattock) in the women’s journal Tidens Kvinder, no. 12, 1935

Radical Eros

Vitalism, sexual romance are terms denoting a quite special assimilation of psychoanalytical theory on the significance of ‘the erotic’ – in English-language literature this is particularly exemplified in the work of D. H. Lawrence, with his accent on sexuality as the central aspect of the relationship between the sexes, the cultivation of primitive eroticism. In this song of praise, women were reduced to nature and body, but not only in the conventional sense of becoming ‘sex objects’ for the male libido. Literary vitalism was also an element of a cultural and literary campaign in which elements of the male literary dynasty in the United Kingdom and Scandinavia set themselves up as literature – in this particular case, modern literature – incarnate, and from this position they disseminated a really quite narrow perception of sexual liberation. In this literary milieu, then, women had to simultaneously recast pen and body.

The Norwegian poets Aslaug Vaa and Halldis Moren Vesaas are examples of what could be called vitalism with a female subject. They write a quite special version of erotic poetry, with woman as the desiring subject. In their work, and also in that of a number of other writers, from Icelandic Hulda to Finnish Aino Kallas, the mystery of the earth and nature is rendered in images – not of the woman herself but of the erotic encounter, while nature appears as a double-image: both the arena of female biology and a picture of freedom and creativity. Nature opens up to women’s dreams and activity at the same time, does not close around a sexualised female body in a narrower sense. Nature lies beyond narrow social restrictions and power structures.

Female eros does not only spread from body to nature. Finnish Helvi Hämäläinen describes the erotic revolt against bigoted sexual norms as the starting point for a far greater urge for freedom, while Aino Kallas sees women’s longing for sexual pleasure, for freedom and execution of creative power, as a norm-exploding force. Women’s erotic experiences do not end with sexual intercourse, but include pregnancy and childbirth with attendant physical and spiritual transformations. The perception of libido expressed in the women’s writings breaks the pairing of sexuality with the young, sexual female body. For the women, libido is linked to the body’s story, its births and ageing, it is linked to the mind, paths are opened between flesh and spirit – for example, towards the intellect which a Lawrence sees as subordinate in the sexual relationship – and, finally, libido becomes an expression of a radical or even anarchic urge for change.

In Denmark and Norway, the cultural radicals were indeed also concerned about sexual liberation and the veneration of nature, but in a less Romantic and mystical variant. Norwegian Sigurd Hoel’s novels Syndere i sommersol (1927; Sinners in Summertime) and En dag i oktober (1931; A Day in October) are typical examples of focussing on the overriding significance of libido, and the conservative critic Eugenia Kielland (1878-1969) objected strongly to his view of human – and not least female – nature. Of the female characters in Syndere i sommersol she writes:

“All of them want one thing only, to seduce and be seduced, every action is determined by sex, and risqué physical innuendo (which the prophets of free speech do not miss a chance) must substitute for spiritual features […] The case with Hoel is probably like that of other so-called misogynists: they are only interested in women they have some cause to despise.”

“The radical trio” – Arnulf Øverland, Sigurd Hoel, and Helge Krog – were dominant figures of Norwegian cultural radicalism, the ‘members’ of which were all men, even though Nini Roll Anker had a good relationship with the three. In response to their view of women and human nature, Eugenia Kielland had the sharpest pen; in a 1934 article published in the literary journal Samtiden, she characterises Hoel’s works as “an intelligent, but somewhat sterile, cerebral product”, and goes on:

“The author is not lacking in inventiveness; but his imagination is abortive, it does not produce living offspring.”

In the same way as Danish digestion of psychoanalysis was centred on instinct theory and passed over the subconscious, so the radicals used ‘reason’ and ‘education’ as keywords in the discussion of sexuality and gender. And it is striking that psychoanalyst, sex educator, and author Jo Jacobsen’s large-scale erotic women’s project is based on a social critique with education as its leading issue.

Female Eros as Social Utopia

“When I dream of what would be my great happiness, – she said, – it is to want a child with the man I love, – and for us to long for this together.” Thus says the central character in Jo Jacobsen’s (1884-1963) first novel, Hjertets Køn (1924; Gender of the Heart). In her works of fiction and on sexual politics, the pivotal point is always the female mode of love as combined desire for man and child. Herein, she finds the key to women’s minds, the fate of children – and of world history. And in oppression of the female eros she finds an explanation for the oppression of and damage to children – Det er ikke til at vide … (1935; You Never Know…) – and for men’s brutality, the triumph of power and war.

In the legend En sang på trapperne (1949; A Song in the Offing), Maria fights an ongoing battle against Godfather’s lust for power that makes him sow discord in the human mind, makes men more interested in the sword than in love, creates hatred between father and son, mother and daughter. Jo Jacobsen fights an impassioned battle, alongside her rebellious Maria, against the western Christian culture’s institution of the Oedipal hatred/love-triangle of father, mother, child, and against the perversion of the death instinct into an ill-fated complex of angst and destructive instinct.

If the mother feels rotten, then her ability to love will be stunted and the children damaged. The weary, impoverished mother with the drunken husband in the collective novel Marsvinjægerne (1928; The Porpoise Hunters), for example, turns her anger against her daughter, whom she ill-treats. This is the negative image of the happy fulfilment of humankind – which is inhibited when social need and financial and political oppression lays a clammy hand on the women’s lives.

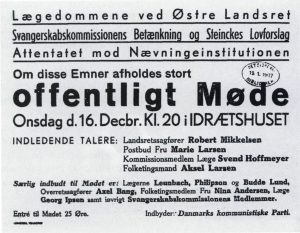

Jo Jacobsen whipped up most notoriety via her activities concerning sexual politics, as educator for children and adults and as vociferous proponent of a woman’s right to termination of pregnancy. All human need is concentrated in the proletarian woman, who is put through any number of pregnancies to produce a surplus of workers for the industrial reserve army, prostitution, and war; in the pamphlet Fosterfordrivelsesparagraffen 241 – Tvangsfødsel eller Forebyggelse (1930; Foetus Expulsion article 241 – Forced Childbirth or Prevention), the fate of the impoverished woman is one of Jo Jacobsen’s most forceful arguments for women’s right to contraception and abortion.

In 1932 the Danish “abortionist” J. H. Leunbach published a series of letters from Kvinder i Nød (Women in Need), illustrating the background to, for example, Jo Jacobsen’s campaign against “Fosterfordrivelsesparagraffen, § 241” (Foetus Expulsion, article 241).

“Dear Doctor Leunbach. I have bought one of your pamphlets and therein read that we may write to you about everything we have on our minds, and of this I shall now make use. I am so horribly ill and wretched, and afraid that I am expecting again and that is almost unbearable to think about, now I have had six children in seven years and I am only twenty-eight years old and given that I was ill the last times I fear the worst; I am becoming quite peculiar in the head. Should it be possible, would you please help me with good advice, is there really no alternative in this case? Are there no doctors in … you could recommend I visit and who really can and will help me? I am not so far advanced, I have had my monthly periods regularly up to the last time it was overdue, do you then think it is dangerous or against the law when it is no further advanced? I eagerly anticipate your reply and will be very disappointed if you do not think it will help me any that I go to a doctor … Yours, Mrs …”

In Denmark, from the mid-1930s, there was a growing sexual-political movement strongly inspired by the psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich (1897-1957) and his ideas about the connection between sexual and political oppression. From 1937 until 1940, the Sexuel Sundhed (Sexual Health) society published a periodical called Sex og Samfund (Sex and Society) that achieved a circulation of ten thousand plus a number of court cases for immorality – cf. the Swedish Riksförbundet för Sexuell Upplysning, RFSU (Swedish Association for Sexuality Education) and Norwegian sex education.

Sweden’s leading sexual reformer was Norwegian-born Elise Ottesen-Jensen (1886-1973). She began her career as a journalist at the Social Democratic Ny Tid in Oslo followed by Arbeidet in Bergen, where she started a women’s discussion group that tried, with some degree of success, to organise maidservants and female textile workers. In 1913 she met syndicalist and anti-militarist Albert Jensen and moved to Sweden. Beginning in the 1920s, she held widely acclaimed educational lectures throughout the country. Her battle with the law against contraceptives (which was not repealed until 1938) produced Ovälkomna barn (1924; Unwelcome Children), Könslagarnas offer (1927; The Victims of Sex Legislation), and a book of short stories entitled Människor i nöd – det sexuella mörkrets offer (1932; People in Distress – the Victims of Sexual Ignorance).

She founded the Swedish Association for Sexuality Education (RFSU) in 1933 and chaired it until 1959. Her two-volume autobiography is entitled Och livet skrev (1965; And Life Wrote), and Livet skrev vidare (1966; Life Wrote More).

It is within this movement that we find Jo Jacobsen who, in addition, made an impact with her continual assertion of the maternal and the childish as the source of life instinct and freedom. Her educational publication Seksualreform (1932; Sexual Reform) is both a psychoanalytical account of the moulding of life instinct and a campaigning text for the female body, the health and beauty of which she sees falling into decay under an anti-love morality and the debilitating childbirths.

In Jo Jacobsen’s writing, anger at injustice, horror at brutality, and ardent celebration of the utopian force of love go hand in hand with an educational enterprise that leaves her particularly exposed to satire and ridicule. With her book Kærlighedslivets Labyrint (1944; The Labyrinth of Love-Life), she takes an initiative that is both naive and epoch-making. Here her burning ambition is to educate children, and she calls for material such as films, songs, and comics about sexual life – her contribution being stories about how the spermatozoa propose to “Æggepigen” (the egg girl), and short songs with clumsy metrical feet sung to familiar tunes. It is a pioneering work, but both too impassioned and unpragmatic to be taken up by the other ‘sexual politicians’ of the day. Jo Jacobsen has more in mind than information.

She has the vision of the opportunities afforded to innocence and childhood when allowed to develop through voluntary sublimation. This vision lies at the root of her novel Det er ikke til at vide …, which she published under the pseudonym Frese Olsen, with prefatory recommendations by both Sigmund Freud and the Danish Minister of Social Affairs K. K. Steincke. Here, she tells the story of a poor fisherman’s family in which the worn-out mother is mostly alone with a steadily growing flock of children. The children’s upbringing consists of beatings and suppression of everything to do with the development of body and libido, all under the threatening surveillance of religion. There is a ‘madhouse’ close to their home, a further comment on the result of people’s oppression of one another. One by one the children are browbeaten; at the heart of the story is a little girl whose rebellion, lust for life, and pleasure in the body are cut short by fear of losing her father’s love.

Jo Jacobsen’s mixture of orthodox Freudianism, a touch of routine Reichianism, and a completely personal, passionate belief in woman as the central character in the story about love, religion, and generations, stands strangely alone in its day – but in all its affectation and naivety it also anticipates a far more modern view of child, woman, and eros.

Jo Jacobsen’s destiny was first parody and then oblivion; she was pushed to the sidelines, marginalised, albeit all her endeavours were directed at fitting the female libido, motherhood, body, worker, into the heart of society as key forces behind a new and loving development based on an angry showdown with oppression and suppression. Here she embodies the paradox for women’s writing: with formal victory for the women’s movement after the First World War, it is obvious that women’s new position in societal and cultural life is an important factor in the process of modernisation, but at the same time they represent what cannot be modernised. They are simultaneously central and delimiting. Literature written by women thus also becomes an insistence on being visible and wholly integrated in the historical process. But it also bears witness to the women’s split minds about, and hesitation over, things modern. The Danish realists Johanne Buchardt, Aase Hansen, and Ellen Raae express deep ambivalence about the costs of a modern life for women. In their books, body and love, the female emotional life, are a shadowy point, lost in town and city, mass society, the workplace. Reproduction, which did not come under the equality umbrella, comes along as a conundrum, a feeling of alienation.

Between Jo Jacobsen’s vigorous insistence on women’s place at the centre and the hesitant realists who circle round both the body and the modern, there is a series of positions cutting across the regulated access: here we find the lesbian, the androgynous woman, the deliberately childless, the twentieth-century heroines who fall out with the most dogmatic and seductive answer to the crises of the era and of the sexes.

For nine years, Kvindernes Oplysningsblad (Information Journal for Women) was the forum for a ground-breaking debate on working-class women and sexual politics. Both the journal and the debate came to an abrupt end in 1934 when the Communists changed tack. Two years later the prominent political figure Marie Nielsen was expelled from the party for the third time – for Trotskyism.

The Fascist Female Body: Blood-Motherhood

To the unexpressed longing, there was at the time a seductively straightforward answer: motherhood as realisation of the female nature – and as protest against men’s dominance. In En Mor (1919; A Mother), Olga Eggers depicted a family life in which the foundation stone is the harmony that evolves between mother and children, while the man becomes increasingly marginal. The meaning of life culminates in love of the child: “The living child whose yet half-dormant mind held the promise of eternity.” In Eggers’s writing, the significance of motherhood grows in response to the modern conflict between the threat of free sexuality and the threat of a loveless, emancipated working life. Her personal path led from this point to Nazism. This is where we also find Norwegian Cally Monrad (1879-1950), once a celebrated singer, who in 1940 joined Vidkun Quisling’s Nasjonal Samling (National Unity) party.

Vidkun Quisling (1887-1945) formed the Norwegian Nasjonal Samling (National Unity) party in 1933; in 1942 the Germans made him minister-president of Norway. After the war he was convicted of high treason and sentenced to death.

Her collections of poetry hold a mythical longing for coherence and fusion, religious pondering, and an idealistic belief in the greatness of the spiritual individual. Barbra Ring (1870-1955), who found her place in Bondepartiet (the Farmers’ Party) – the party Quisling left to set up his own – spent the 1930s deeply absorbed by developments in Germany; in 1935-36 she compromised her reputation by opposing a public statement signed by thirty-three writers in support of the German pacifist Carl von Ossietzky’s award of the Nobel Peace Prize. She shared Fascism’s cultural critique of the destructive effect of civilisation and rationality on traditional familial ties and on motherhood. But when Nazi Germany occupied Norway, her sympathies deviated from the forces that now proved to be a threat to the Norwegian connectedness to the Norwegian soil.

On the outer edge of feminism, disappointment about things female not meaning enough under the new ways of life – and realisation that it might, at most, be possible to make room for women in the men’s ranks – led to the development of an anti-modern feminism that flirts with the Nazi and Fascist view of women.

This is developed in Denmark by, among others, Esther Bonnesen (1892-1953), one of a group around the declared conservative, Christian, and in the 1930s to some extent pro-German journal Det tredje Standpunkt (The Third Standpoint). In her book Evas Ansvar (1938; The Responsibility of Eve), she gives her version of cultural developments of the twentieth century so far.

In the twentieth century, she says, what she calls “phallic worship of life”, a male principle, has defeated the female principle, “the family-bound and soul-bound lovelife”. Sexuality and reproduction have been separated, and this state of affairs is an attack on female chasteness. This lopsided cultural development is, however, the responsibility of the woman, “Eve”: the women’s movement has allowed the development to take place in the image of the man, the law of a degenerate civilisation has through this been allowed to defeat the la w of nature which women represent. The women protest at the development by refusing to love the derailed men; instead, they have thrown themselves into male outlets such as flying sports planes and writing dissertations, have become sterile. They now ought to assume responsibility for the decline of culture, institute the law of nature that is stronger than the phallic one, and through this re-educate the men to be lovers and fathers. Rather than counting on materialism and the sceptical intelligence, women should again allow the special womanliness, the maternal nature and a “synthesising and intuitive form of cognition” to have pride of place.

The essence of Esther Bonnesen’s not always lucid mindset is a reading of the two sexes as opposites, in which the woman is bound up with nature and the continuation of the family line. And the men would have to be persuaded to acknowledge this bond as a cultural and human value. She does not blame the liberated women for flying and thinking rather than giving birth to children, but she diagnoses their lives as symptomatic of defeat at the hands of the man and as alienation from a true female outlet. And she seductively promises real influence and power to those women who shoulder the undertaking. It is part of the story that, in the Nazi context, where women’s identity as mother, their binding with blood and soil, their “Blutmutterschaft”, were taken seriously, they are second-rate citizens who were forcibly removed from the workplace in order to bear soldiers.

Motherhood and Dream Vision

The fate of mothers in literature written by women has been, at one and the same time, to embody the nightmare and the utopia. The Finnish writer Maila Talvio (1871-1951) sees motherhood and mothers alike as suffocating; in Agnes von Krusenstjerna’s works, witch-like, domineering mothers exist side by side with the dream of an innovative matriarchy – mothers are worn-out, they are domineering. Moa Martinson depicts the mother’s dual identity as a conundrum faced by the daughter, the conundrum of women’s sexuality and fecundity and their ambiguous relationship to the both desired and domineering man.

Motherhood itself, as symbolic of the woman’s connection with the earth and with nature, is also ambiguous in Helvi Hämäläinen’s impassioned contribution – pro-motherhood and against the painful consequences of abortion – in the Finnish debate on abortion; along with the traditional picture of woman in concord with Mother Earth, there is an insistence on woman’s twofold right – to motherhood and to sexuality.

The new ‘morality feud’ was concerned with more than sexuality and abortion; the whole area of reproduction was put to debate: the right to pain-relief during labour, financial support for families with young children, domestic help, childcare institutions. Population policy became an important issue.

In 1926 Arbejderpartiet (Norwegian Labour Party) took over the running of the first “Mødrehygiejnekontor” (Mothers’ Health Office) in Oslo, set up two years earlier on the initiative of Katti Anker Møller, and in Denmark the opening of “Mødrehjælpen” (Mothers’ Aid) and the introduction of health visitors for families with infant children were important social and welfare schemes. From the mid 1920s and up through the post-war period, not only were the issues discussed, but deep political and social (and moral) changes were implemented in the lives of women and families. Many areas of work were pushed out of the home, were monitored by the authorities, or were simplified – by the 1960s ‘home, husband, and children’ was defined as part-time work.

In Norway, Katti Anker Møller (1868-1945) was the pioneer of work for “voluntary motherhood”, and in the early decades of the twentieth century she campaigned for the legal rights of single mothers and their children, and she canvassed for guidance about contraception, for guidance for young mothers, and for the abolition of article 245 of the penal code, which set a sentencing option of three years’ imprisonment for women who underwent an abortion.

This was the Nordic solution to the new conflict between the sexes as equal parties and the women’s continual insistence – in their new political life and their literature – that the body, the birth-giving, their entire life and needs should have a place within the societal framework.

The highly esteemed Danish philologist Lis Jacobsen (1882-1961) was, in life and in writing, a striking example of the intense tension between motherhood and independent personal development. She repeatedly advocated “matriarchy”, a social order in which women devote themselves to having children (five-six per mother) from the age of twenty and, in return, have real power as the focal point of the home. She later realised that the tension could not be resolved quite so simply:

“For the women who have an urge to pursue another calling […] it would be suicide to crush this urge – even if one could be the mother of twelve sons; but, conversely, the woman who, for the sake of her work, forgoes motherhood, would not be a whole and complete person. If one wants a life, one has to fight for it.”

Kvindelige Akademikeres Jubilæumsskrift (1925; Female Academics’ Anniversary Publication).

In the midst of modern-life conflicts, motherhood might seem like a deus ex machina solution to the feeling of loss and lack: child-bearing and maternal identity step into the empty space in women’s lives and provide substance and significance. This is the case in the work of a number of less well-known Danish writers: Minna Vestergaard (1891-?) in Vi Fraskilte (1939; We the Divorced), Ellen Kirk (1902-1982) in Oprør (1932; Rebellion), and Alba Schwartz (1857-1942) in Skilsmissens Børn (1936; Children of Divorce; adapted for the cinema by Benjamin Christensen and filmed in 1939). Alba Schwartz writes about the terrible consequences for a family in which the parents’ incompatibility has led the wife to leave home. The whole plot is played out in the context of the absent wife: the home loses its charm, the husband spends a lot of time with his mistress, and the two abandoned children lose their social anchor and compass. They lose their way in life: the boy runs away from his boarding school, driven by longing for his mother; his older sister embarks on a sexual relationship and gets pregnant. Alba Schwartz presents the mother as guarantor of coherence and continuity in the lives of her children and her husband; she it is who makes for meaning and order, not least by means of the love and solicitude she can invest in management of the family.

Ellen Kirk and Minna Vestergaard locate their perspective in the mother herself; choosing motherhood gives the women meaning. The central character in Oprør, sullen and passive Ingrid, has very little rebellion in her when she happens to fall pregnant. She is stuck between her husband’s conventionally boring family and her more beautiful sister’s and mother’s glamorous and shallow lives. Her life has no direction, and the child on the way has three possible fathers. And then, during the actual birth, a transformation occurs, and new options suddenly open up: “The little baby in her arms filled her with a supple strength that ran like a steel spring through her spine.” The child gives her both physical and mental strength and direction, and she can opt out of the false alternatives: strait-laced respectability versus vacant glamour. She chooses a third way and moves into the countryside with her female friend. And thus, nature and motherhood come to her rescue, because Ingrid has long since abandoned the attempt to find a meaning and an ethic that could provide her life with parameters and her person with vigour.

The special aspect of Minna Vestergaard’s story is that it is not biological but chosen motherhood that gives meaning to divorced, self-supporting Gerda. She leaves her indifferent marriage in order to try her luck in the workplace, where a financial crisis and aggressive men vie to ruin her chances. Gerda is the casualty of heavy contemporary odds that prefer young and cheap hands, of an unscrupulous baker who swindles her out of her last savings, and of a lover who disappears in her hour of need. Her final salvation is a job as matron of a boarding school, where she is “mother to one hundred and thirty boys”.

Around her, other women seek to overcome their divorces, one dies of her husband’s desertion, of exhaustion and pneumonia, another, parallel story, ends in sheer idyll when man and woman are united, accepts their child born out of wedlock, and are expecting another one.

It is interesting that Minna Vestergaard explained her novel as a plea for women to stay in the home – “here she, nevertheless, in spite of everything is of most use” – and for greater female self-effacement, while the actual storyline expresses a veritable fury against the men, culminating in the portrait of the baker who, appallingly with his hairy arms kneads the very dough that, as future nourishment, was to be Gerda’s financial basis, until it takes on “a brownish-black, nasty colour”. Faeces – that is what the man makes for the woman. And she, with crystal-clear validation, claims something else, and something more.

These images of the power of motherhood contain a deep and distrustful resistance both to the men and the entire development of societal life. The resistance has become absolute, but this also means that the body and sexuality have been minimised. What remains is a simple assertion of female superiority in the sphere that was the problem child of the era: human reproduction as a matter for women and men, politics, and desire.

Anne Birgitte Richard