“Saa er jeg fri!” are the final words and the title (Now I’m Free) of the last novel written by Hulda Lütken (1896-1946), published in 1945 – when Hulda Lütken had a long list of poems and novels to her name.

“In the afternoon I was going to write. There was something I would have written: an idea. Anna had gone […] Towards evening I gave up. I had written ten pages about nothing. Ten ridiculous dull pages, utterly lacking in talent – and without any idea. The idea had flown. I sat and smoked. The pain had grown to tears pressing in my chest […] Everything was deathly still. I sat in a grave and smoked.”

Saa er jeg fri (1945; Now I’m Free).

The novel’s male narrative voice says this “Now I’m free!” – calling himself after Barabbas, the man chosen by the crowd to be released rather than Jesus. The narrator is a Barabbas, but also a writer whose art is nourished by offences committed against the good, the true, and the beautiful in the shape of the women he seduces and abandons, and in the shape of the image of Christ that he finally shatters. The narrator is an artist of darkness, dwelling on corpses, craniums, and churchyards. He sucks milk from a lover’s breast so as to feel momentarily alive, and he eats death and transitoriness from the hand of a whore. At the start of the story, he is having a creative crisis – nothing can nourish his words any more – and he hires young Anna as maid and potential fodder for his new work of literature.

In Anna’s case, however, no quantity of seduction techniques, craniums, or commands about the animal in the human are of any help. She will not be destroyed for the sake of art; she leaves him, with no further explanation. This time, therefore, he cannot simply obliterate the woman, but has to shatter the image of Christ in order to achieve the destructive freedom that is the prerequisite for his “devilish” writing. “Now I’m free!”

The male narrator from Hulda Lütken’s final novel gets a more manageable and conciliatory kinsman in Martin A. Hansen’s far-famed novel, originally commissioned for radio by Danmarks Radio (Danish Broadcasting Corporation), Løgneren (1950; Eng tr . The Liar, 1954). The first-person narrator here, Johannes Vig, cannot compare with Hulda Lütken’s wild, destructive Barabbas in terms of inner battle or death drive; however, Johannes Vig does actually share some attributes with Hulda Lütken’s less well-known fictional character: gun-dog, obsession with the devil, maid, a dead young man, and the humiliation of a woman’s departure. Hulda Lütken’s portrait of her man thus provides ambiance to the moods and motifs in one of the most famous works in the Danish literary canon.

Above all, however, Hulda Lütken’s dense and keenly atmospheric little novel should be read in connection with her major autobiographical prose work Mennesket paa Lerfødder (1943; On Feet of Clay), in which she carries out a painful process of self-analytical confrontation. And the first-person narrator in Saa er jeg fri proves to have biography and world of ideas in common with the autobiographical female voice in Mennesket paa Lerfødder. They are both writers, they both return to the same childhood experience of fear and fascination with the dark, the moon, and the church tower – symbols of, respectively, death, female sexuality, and male sexuality. The male voice harbours hatred of the moon, whereas the female voice tells of her childhood pact with the moon, but also of her later insight into the nature of the moon: “At that time I didn’t know that the moon is deceitful. Now I know […]”. The male narrator seeks shelter from the moonbeams by the church tower; the female voice flees from the tower and the church, out into the moonlight. But while, at the end, the female voice in Mennesket paa Lerfødder lets the church tower crash down on her and accepts the cross of Christ in a grand Easter apotheosis, the male narrator smashes the cross and goes on to freedom, creative art, and thereby crime, as reflected in Barabbas’s final words.

“But I recall a time when I was not wicked – when I delighted in the flowers on which the sun shone – my eternal time – before I became conscious of myself as human being – before heaven was taken from me,” writes Hulda Lütken of her childhood in Mennesket paa Lerfødder. She was the daughter of a teacher, had gypsy blood in her veins, and was born and grew up in Elling, in the Vendsyssel region of northern Jutland, where she also lived for most of her adult life – with periods spent in Copenhagen, where she participated in the cultural life and socialised with the literary journal milieu. An early marriage ended in divorce.

Line, themes, and motifs constantly converge in the two prose works Saa er jeg fri and Mennesket paa Lerfødder. The male voice in Saa er jeg fri resembles the female creative artist in Mennesket paa Lerfødder, a woman plagued by the accusations of her fictional characters: “You killed us! We didn’t exist, but you created us. And look, now we’re dead!”

The female voice in Mennesket paa Lerfødder (1943; On Feet of Clay) recounts a number of her dreams – in which she typically features as a man. “I am often a man when I dream – I know not why. Perhaps deep inside me there slumbers a man, whom I do not know, but whom I once have been – who knows?”

The female voice ends by renouncing art and tale in favour of a Christian creed and release from the Barabbas stone she wears around her neck. This is not the art of novel-writing, “[t]his is the book about a soul”, states the final line. In Saa er jeg fri, however, Hulda Lütken returns to tale and art with her male narrator, and creates a work that is sensitive to the tiniest detail and quite different from the highly fragmentary and at times immensely long-drawn-out narrative style in Mennesket paa Lerfødder. The conclusion would seem obvious: Hulda Lütken, whose aim was to articulate a female voice in her writing, was actually most successful as a male narrative voice or as the third-person narrator in her major family saga De uansvarlige (1933; The Irresponsible Ones).

“Anna has left. Why? No one knows. No one knows woman. I don’t. A pair of blue shoes here and a striped apron hanging in the kitchen… I start ripping it to shreds. Caso looks on, barking. Belt up, Caso! And don’t just stand there howling. The girl’s damn well bolted. That’s it! Over!”

Saa er jeg fri (1945; Now I’m Free).

This conclusion must nonetheless be examined one more time, because the male narrator in Saa er jeg fri does not succeed in his attempt to transform young Anna into art and by so doing incorporate her in his ‘creative’ house of horrors of breast-feeding mothers, virgins, and whores. His late-Romantic gallery of women does not work vis-à-vis this young woman with a tangled love life and the urge to get out in the world. She simply leaves him. The female first-person remains an aside in the story told by the male voice, and it is the very difficulty in narrating this ‘I’ or letting her speak up for herself that makes for the energy and tension in Hulda Lütken’s writing. She shares this concern with her contemporaries Bodil Bech (1889-1942) and Tove Meyer (1913-1972).

Tove Ditlevsen describes the first time she met Hulda Lütken:

“Viggo F. comes in with a sparkling, plump, dark little woman who shakes my hand as if she means to tear it off, and says, ‘Hulda Lütken. Huh… so that’s what you look like. You’re becoming so celebrated it’s almost unbearable.’ Then she sits down and speaks the whole time to Viggo F., who finally asks me to leave, because there’s something he wants to talk to Hulda about. Later he explains to me – what he has already hinted at – that Hulda Lütken can’t stand other female poets.”

Ungdom (1967; Youth, Eng. tr. with Barndom as Early Spring)

“…I Do Not Belong Here”

Late-Romantic writing – the finely evocative images and the state of the first-person’s inner mind as reflected in nature – is the primary background to the work of the three writers. Danish poets of the 1890s – such as Viggo Stuckenberg, Ludvig Holstein, and Helge Rode – are among the key sources of inspiration. In this late-Romantic writing, we hear the ringing of delicate silver bells, the dew flows towards the heart of the earth, stars fall miraculously, and herein the ‘I’ faintly spies the depths of the soul and sensitive moods of joy, sadness, and anxiety. A female character is often to be found at the centre of this poetic universe. She moves in the emotionally charged sphere and totality which the male ‘I’ seeks and sees but faintly.

These are the clear days,

when the morning sky turns blue,

and the day gently shines,

until the grey of evening.

Where are you now, sweetheart?

I can no longer see you!

across the hinge of my gate

a spider’s web is hanging,

and never has it broken,

dewdrops keep it moist

all through the day

as if forever weeping.

Viggo Stuckenberg: “Høst” (Harvest), Flyvende Sommer (1898; Flying Summer)

She is the beloved, the emotion and soul – like Ludvig Holstein’s sweetheart in “Vil I kende min Veninde” (Would You Like to Know My Sweetheart), Digte (1895; Poems), Stuckenberg’s “Ingeborg”, Sne (1901; Snow), and Helge Rode’s princess Tove in “Skjaldens Sang” (The Bard’s Song), Den stille Have (1922; The Quiet Garden).

The female characters belong to a landscape and cosmos of the soul; the male poet has a share in this by allowing the poem to convey her experience, or, like Stuckenberg in his poem to his wife, by looking into the clear plains and dense groves of her soul. In the work of Hulda Lütken, Bodil Bech, and Tove Meyer, this dreamy female figure is given a voice; she becomes an ‘I’ – which proves to be a route out of the late-Romantic universe.

Jenny Blicher-Clausen (1865-1907) is a contemporary of male late-Romantic poets such as Stuckenberg and Rode. She is best known as the author of what was at the time an enormously popular Künstlerroman, Inga Heine (1898). When he was a young man, the eccentric and out-of-favour composer Rued Langgaard, in whose music late-Romanticism finds dramatic expression, wrote a series of atmospheric songs to poems by Jenny Blicher-Clausen. Her delicate verse, as interpreted in his music, is rendered beautiful and singular. Rued Langgaard is clearly fascinated by the enigmatic female voice in the poetry, whispering about flowing dew, the sound of tiny bells, and moths’ wings. On one of the recent recordings of Rued Langgaard’s works, which have seen wide recognition in recent years, soprano Birgitte Lindhardt and pianist Ulla Kappel render Langgaard’s songs to Jenny Blicher-Clausen’s poetry.

There was already an understanding that late-Romanticism leads to a silent point, where the harmony disintegrates, in the work of female Swedish poets of a slightly older generation, such as Karin Ek, Jane Gernandt-Claine, and Harriet Löwenhjelm. Exposure to Edith Södergran’s transformatory language was to be the decisive inspiration for Danish poetry – from the surrealists and the poets associated with the journal Heretica to the mutinous poets of the 1960s and new generations of poets in the 1980s.

The power and expressivity, the new, demanding ego that was given voice in Södergran’s writing, first made its mark in 1930s’ Denmark in the work of writers connected to the arts journal Linien – such as Hulda Lütken and Bodil Bech.

Linien was published for a brief period in 1934, and brought together artists and writers in support of a surrealist programme – among others, Gustaf Munch-Petersen and Jens August Schade. Even though French surrealism was on the journal’s agenda, the common vision was for a break with naturalism’s view of human nature and a longing for rebellion in the arts. Darwin and Freud were the subjects of a programmatic renunciation, from an understanding that they had stripped humankind of divinity and creative powers. Freud had reduced humankind to “meagre information about what transpires in the life of the mind”; once art had made it a mission to “rape cultivation”, however, it could again get in touch with the mighty creative power of the human being. The interest was not in sexual drive in Freud’s sense, but in a bigger and, above all, creative power of eros – which largely proved to include what Freud would label libido.

Edith Södergran’s writing was seen to hold the sought-after new strength of image and idea, and the creative power in humankind. In Bodil Bech’s and Hulda Lütken’s writings, inspiration from Södergran is seen as an intense provocation of the traditional late-Romantic verse language and poetic fixtures. It is tempting to say that the Södergran influence takes their writing to the verge of breakdown, whereas the third woman poet of the 1930s, Tove Meyer, lives and writes for long enough to accomplish the difficult manoeuvre out of late-Romanticism and into a new modernist style.

The Norwegian late-Romantic women addressed the thematics around self, presentiment, eros, and the inexpressible; in the work of, for example, Cally Monrad (1879-1950) we read:

Now a storm is raging.

Now my heart is turbulent

and fearful of the dark

and the long night.

But mostly of the day –

Ah, for the one approaching:

the grey, terrible day.

Now I am at the mercy of my turbulent heart.

My mind is frozen

and my spirit broken.

My song, which rang out,

flows now in tears –

Ah you … you alone …

I love you …

“Storme II” (Storm II), Nye Digte (1919; New Poems)

“… Along the Golden Rivers of My Longing”

In book cover and vignette, Hulda Lütken’s debut collection, Lys og Skygge (1927; Light and Shadow) follows the 1890s aesthetic and opens up a traditional late-Romantic mental landscape of feelings and eternity:

… I shall wander there,

where the forest soughs as if of eternity,

along the golden rivers of my longing

to a solitary place I know.

– we read in the poem “Længsel” (Longing). The female voice belongs to a harmonious spiritual universe, but this promised land soon proves to contain fierce forces of instinct and death. The poems oscillate between omnipotence to enter a wonderful coherence and rhythm of life and soul, which only the ‘I’ can see, and impotence in the face of death and the ‘you’, which she encounters everywhere. And Hulda Lütken tries to use the traditional poetic topographies to convey this tension. She deals with a love and instinct that leads into a cosmic coherence and unity, but the route always seems to lead to the ‘you’ and to death. In her fourth collection, Elskovs Rose (1934; Love’s Rose), she tries to maintain the ‘I’ longing for nature’s grand ‘you’ as a contrast to the mortal I-you-relationship:

I know not where you live;

but you live here in space.

Under the star, under the heavens,

under the golden passage of the moon.

Every place, everywhere,

I can sense your breathing.

Never am I lonesome;

For your breath lives yet.

Anne–Marie Mai

“… Now the Moon Was There Again”

In Hulda Lütken’s writing, female longing finds space and expression in nature – which plays both a freeing and a demonic role – and, in her prose works, nature becomes the subject cluster around which plot and conflicts revolve.

Nature becomes a forum of sorts for female opportunity on the route away from ‘the man’s house’. In her first prose book, Degnens Hus (1929; The Deacon’s House), the Deacon is described as an anaemic Ahasuerus figure who, with his abstractions, his intellect, and his delicate physique, is continually on the verge of madness. His wife, Lina, cannot find space for her passion and her longings in relation to him. As if from inner compulsion, she is forced out into the night, out into nature. Here, she finds the closeness and the sensuality lacking in her life with her husband.

In Lina’s sensual-physical fusion with the night, the moon is the symbol of female sexuality, interlocutor, and soothsayer:

“Now the moon was there again. It shone on the mother. – To you I gave the dream, it said. You are the soil, the patient soil. You shall suffer with the child. Much seed shall be sown, before humanity shall be attained.”

The picture of the moon shows that it is Lina’s maternal nature – the strong instinct and precise intuition in relation to people in need – that is and should be her identification tag. Her motherliness not only embraces the children she bears, but also her husband who, despite his patriarchal attitude, remains one of her ‘children’ – one of the many she has to take care of. Motherhood, however, is also linked to loss and pain: loss of the boy children who die or go mad because they have inherited their father’s ‘bad blood’! Loss of her husband, who ends up insane, and, finally, losing hope of realising the dreams and intense eros of the night and the moon.

It is left up to the strange, reserved, and wise daughter, Maria Magdalene, to pass on the insight and attention to nature and cosmos that not only her mother, but also her grandmother, possessed. At the same time, however, it is clear that this female alliance with nature also has a tragic element – it is not capable of expanding into a fruitful, living human relationship. As is the case in Hulda Lütken’s poetry, nature and cosmos here reveal conflicting forces.

Passion and Demony

The beginnings of a demonisation of nature, for which Degnens Hus sets the scene, is intensified in Hulda Lütken’s next novel, Lokesæd I–II (1931; The Seed of Loke, I-II). The field of tension is intensified; female passion now comes across as power that leads to death and perdition.

The young gypsy woman Tore lives like a desperado, leading a split existence in which she restlessly roams between spiritual confinement in her husband’s house and an attempt to release her irrepressible passion in nature. However, while nature is described as the arena for her unfulfilled longings, this very nature is also strongly demonised. It becomes a power, rendered independent in the form of the mysterious gypsy Loke, who entices and seduces Tore to a passionate destruction of husband and home – quite literally: she ends up murdering him and burning their house down.

With the help of this romantic-mysterious story of enticement, Hulda Lütken is able to present Tore as simply the medium for the wicked seducer, Loke. The story of enticement should also be read, however, as an aestheticised camouflage of the evil and desire for destruction that is ascribed to woman, but which the novel cannot voice, and which is therefore displaced to the forces of nature that become the actual subject for destruction and wickedness.

Tore’s ultimate, passionate and destructive, alliance with the gypsies in order to destroy the marital setting, which gives protection from the outside world but which also stifles her vitality, is also connected with a tragic childbirth. She gives birth to a stillborn boy. Where motherhood in Degnens Hus maintained Lina’s connection to reality, the consequence of Tore’s ‘failed’ motherhood is that she has nothing through which to live out her longings, and she is therefore dispatched into madness. Woman’s alienation in the world is highlighted here; nature is also being undermined by things male and is thereby drained as a potential place for the woman.

The fateful link between perdition and female passion is foreseen in the story of the dying mother, Augusta, and in her fear of seeing her own “sinful” life mirrored in her daughter Tore’s desire for sexual adventure. Even though Augusta makes Tore swear that she will not replicate her story, it is still transferred, with fateful consequences, to her daughter.

The Loathsome Drive and the Good God

The close connection between sexual drive and death, which is transferred from mother to daughter, is also the central theme in Hulda Lütken’s third novel, De uansvarlige. An entire family living in a gossipy provincial town is again fatefully affected by dangerous and deadly drives. In recent years the mother, Therese, has been in a marital conflict between asceticism and sexuality; as punishment for her sinful youth – the result of which was an illegitimate child – she has joined the town’s Pietist sisterhood.

Therese’s two daughters and their instinct-driven, tragic destinies represent different sides of her conflict. Illegitimate, dangerously seductive Agathe dies a self-caused victim of her own coldly calculating desire, and innocent Erna becomes the victim of other people’s sexual exploitation of her. When the novel opens, Therese’s conflict has reached a critical point. She is told that she will not survive the birth of another baby. In order to stop her husband, Ejnar, succumbing to temptation and falling for the allures of Agathe, Therese sacrifices herself and becomes a martyr for the sake of Ejnar’s religious salvation – a sacrifice imposed on her by the Pietist sisters. However, the novel shows that Therese is controlled just as much by her sexual desire for her husband as she is by the Pietist sisters. Even though the novel delivers a biting critique of the sisters, it is also extremely ambivalent as regards the drives controlling Therese’s longing for her husband. Under the eyes of the narrator, Therese makes the wrong choice. Rather than choosing asceticism and motherhood, the province of life, she chooses husband and sexual drive, the province of death.

“And I saw a young woman approaching us. She was enveloped in flames. She had the mark of the whore on her face. It was Agathe. And I saw that she was naked under the flames. She laughed loudly. But she suddenly leapt towards me and plunged her sharp nails into my throat. I could kill you! She screamed. And I had to fight her to get free.”

Hulda Lütken, in Mennesket paa Lerfødder, describing her dream encounter with the female character Agathe from De uansvarlige (The Irresponsible Ones).

The real victim of the adults’ irresponsible sexuality is their daughter, Erna, who is as yet unaffected by her own sexuality. The innocence of her girl’s mind is elevated to the role of truth bearer; the novel’s longing for a pre-Fall state of affairs is entrenched in her person.

For Hulda Lütken, the Fall is so traumatic a matter that all her writing turns on a re-establishment of the original state of innocence; her yearning to remedy the loss leaves its mark throughout her oeuvre, in the longing for death and the ‘I’ problematics. The ego comes into being with loss of innocence, and its presence is accompanied both by longing for the lost innocence and by a destructive creative urge.

Lis Thygesen and Bodil Holm

Female Ego and the Late-Romantic Universe

It is as if this ‘I am’, which Hulda Lütken wants both to express and to surmount in her writing, cannot actually be contained in her prose or in her poetry. Using intense contrasts, outbursts, emphases, and absolutes, the lyrical imagery tries to show the abysses faced by the female ego and to allow her power to come through in the poetry. However, the language she uses in her poetry is also often locked in traditional rhyme between “rum” (space) and “stum” (speechless), “skød” (bosom), “glød” (glow) and “død” (death), and tied to familiar late-Romantic love scenarios. The clash between late-Romantic verse and the powerful, destructive, and creative ego is perceptible in all her writing. It seems as if the poetic language almost cannot contain and hold what she wants to give voice through her pen.

Lænken (1932; The Fetter) was the title she gave to her third collection of poems; a title that refers directly to one of Södergran’s most famous poems: “Fångenskap” (Captivity) from Landet som icke är (1925; Eng. tr. The Land That Is Not). The animal in the title poem is chained to the ground, and the ‘I’ is similarly bound to language, gender, and the male ‘you’. Even though this ‘I’ can still access the grand context of nature and cosmos and creative eros, nature now repeatedly shows its ‘wilderness’. The land that was promised to the female ‘I’ in delicate late-Romantic verse is either occupied by dangerous forces or it is empty:

Moonlight falls in the midnight hour.

I gaze at length across the open wilderness,

but come upon nothing – only the hopes that died,

and hear the anxious ringing of the heart.

Conflict between the late-Romantic language and the poetic female-I endures in Hulda Lütken’s writing; it is thematised directly in the poem “Kamp” (Battle) from Livets Hjerte (1943; Life’s Heart), which depicts the creation of poetry as drama on the threshold between night and day – a drama in which the speaker grasps the pen like a dagger. Her notion of killing the poetic form in order to get to the throbbing heart itself – the leading thought and original force of art – mirrors the conflict between the traditional language and the new self in Hulda Lütken’s writing. She has most success in transforming the late-Romantic setting into a universe of the ego in the poems in which she abandons a traditional logic in the figurative language and gently renders the images paradoxical, as in the poem “Før syntes jeg” (I Used to Think) from Lænken:

“I used to think that sorrow was something heavy

and full of weeping – deep and bitter tears.

Now I know sorrow is something green and young,

in which my heart longs to live.

“Now I know sorrow is something strangely beautiful,

which lives outside my own breast.

In its secret chamber my heart dreams of

becoming green in deep and bitter tears.”

In her final collection of poems, Skærsilden (1945; Purgatory), written against the background of the German occupation of Denmark in World War Two, Hulda Lütken stops her attempt to project the new self – this she does out of fear of this self. In a personal showdown, she accuses herself and her generation of poets of having forsaken life and God, and having impotently abandoned themselves to death and sexual drive:

“Murder!

This word was stamped in our consciousness.

This word engaged our instincts.

We pulled it forth

from the miry morass,

that was our subconsciousness.”

– she writes in the grand concluding section, “Skærsilden” (Purgatory).

In this way, we created a new literature

where instinct was lord and master – and humankind did not master instinct.

And we denied spirituality in the world,

for these fresh murders did so oppress our consciences.

Hulda Lütken: Skærsilden (1945; Purgatory)

The mind, which should get through to the truth of nature, is written off as obsessed by death, sexual drive, and killing. Eros, which should get through to the cosmos, reveals itself to her as instinct and sexuality. The creative forces, to which she wants to give voice, she now sees as sexual and unconscious drives that have also produced war and devastation. Hulda Lütken’s poetry founders in the histrionic oratorical effect and bitter self-reproach of these broken stanzas. But there is a grandiose finale to her battle with language, eros, and ego. Hulda Lütken seems to express and see through the conflict in her own writing. Perhaps the reason her last work, the story Saa er jeg fri (1945; Now I’m Free), succeeds in creating so clear and strong a narrative art is that here she takes this conflict as her theme.

Candle of Love

Bodil Bech, like Hulda Lütken and also against the background of the German occupation of Denmark, sought a re-interpretation of her writing in her final collection of poetry, Ud af Himmelporte (1941; Out of the Heavenly Gates). But for Bodil Bech, re-interpretation did not lead to a ferocious personal showdown; in her collection Flyvende Hestemanker (1940; The Flying Manes of Horses), too, war is thematised, and in her final collection she completes the rendition of the ego that she had addressed ever since her debut Vi der ejer Natten (1934; We Who Own the Night).

The cosmic drama of life, eros, and death, from which the voice in her poetry arose, was made palpable in war; Bodil Bech saw the visions in her poems as prophesies of a new realm of God that would rise out of the old world.

“War shows its paths,

but the gods walk

along sacred paths.

The line of the gods ought not waste away!”

– she writes in the poem “Gudernes Æt” (The Line of the Gods), Ud af Himmelporte (1941; Out of the Heavenly Gates).

In Bodil Bech’s poetry, the late-Romantic setting of silvery waves, delicate birdsong, young women, and sweetly fragrant hedges is an obvious gateway to a universe of perpetual drive towards life and death.

Södergran’s seeing and compelling poetic speaker is the chosen role model for Bodil Bech’s poetry, and inspiration from Södergran is apparent in the emblems of the imagery: lightning, fire, sister, eagle, tree, and angels. The reader is often taken aback by the speed and abruptness with which Bodil Bech can move from a late-Romantic idyll to a grand vision of the self as seer and shining tool in God’s hands. But it is this religious dimension that makes the tremendous contrasts possible, and her writing culminates in the repeated image: “God gave me His candle / of love to hold.” Instinct and pain, from which the poetic voice grows, is interpreted as a flame of God’s light, and the ‘you’ to whom the ‘I’ has directed her longing proves to be God Himself. The religious staging enables Bodil Bech to bring the strong contrasts into a balance of sorts around the ego.

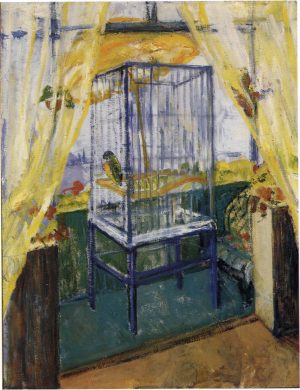

Bodil Bech made her literary debut at the age of forty-five; all in all, she published five collections of poetry. She was born on the island of Funen, daughter of a land owner, and the title of her debut collection, Vi der ejer Natten (1934; We Who Own the Night), plays on the saying “natten er vor egen” (the night is ours), ascribed to the young women of Fyn. Bodil Bech trained at an academy of music in New York; she was also interested in painting – including Harald Giersing’s and Oluf Høst’s work with colour. Bodil Bech died in 1942 while on holiday on the island of Bornholm, where she was staying with her friend Oluf Høst. In the journal Klingen (1917), Giersing programmatically declared that colours should “scream with strong vigour and splendour”; similarly, Bodil Bech endeavours to use colour-adjectives effectively and dramatically in her poetry.

In her debut collection, Vi der ejer Natten, where the poetic setting had not yet been surveyed and mapped out to the extent it was later on, there is already a sense that the ego is a fulcrum of intense forces. In one of her best poems, “I Halvsøvne” (Half Asleep) we read:

“A summer’s eve on the balcony

Verdant fingers of the chestnut playing in the wind

Gratuitous laughter raw in the throat

erupts into the bemused darkening skies

Trains murmur along the tracks

The red pillar shimmers in a shroud of silent mist

The lion groans behind Søndermarken

God the imponderable sends me sleep”

Come stars, come sun, and come moon

in the rainbow play of colours

The palette is placed in the hand

of the one who dreams and dimly sees – and has the will.

– wrote Tove Meyer in her debut collection Guds Palet (1935; God’s Palette); she herself was a painter before she started to write poetry. As in the work of Bodil Bech, colour-adjectives are particularly dominant in her language, also in the often brutal play of colours in her late poems – in one of her best poems, “Solsikker” (Sunflowers), from Brudlinier (1967; Fault Lines), for example:

Seven suns

follow the sun

Seven dark velvet eyes

Seven yellow aureolae

seven suns

fall and rise

each on its

green lance

And green and blue is the flame

on summer’s anvil

Seven suns follow the sun

with velvet gaze

and voice

and seven once so young

turn dark yellow

heavy

like the flame dark yellow

on the anvil of autumn

Seven suns

revered the sun

with yellow

aureolae

seven black scalps

one day hung

on each its

lance.

In the poem’s contrasting of colours, figures, and sounds, the poetic speaker becomes the axis of the sensual, the mythical, and the divine; the axis about which everything can turn and be delivered.

“Was everything in this space sexual – right up to the battle between the sexes? … Was this battle a reflection of God’s battle with Creation – Was Creation a child of the divine – the womb, in which God reproduced? – Was God, the great lover – the true male?” – asked Hulda Lütken in Mennesket paa Lerfødder. However, it is Bodil Bech, more than Hulda Lütken, who is able to realise this interpretation in verse and poem. But, with the idea of the inspired, blazing ego and the grand God-you in Bodil Bech’s final poems, instinct and ego also become far more unequivocal specimens than in Södergran’s poetry.

[…] Give your children a beauty

which human eyes have never seen,

give your children the strength

to force the gates of heaven.

– we read in one of Södergran’s poems “Samlen icke guld och ädelstenar” (Do Not Gather Gold and Precious Stones), from Septemberlyran, (1918; Eng. tr. The September Lyre), which almost provides the title for Bodil Bech’s final collection, Ud af Himmelporte. But only almost, because in Bodil Bech’s work, God opens his gates to the first-person narrator in the form of a middle-aged visionary in a setting of sulphur and destruction. In Södergran’s work, the ‘I’ breaks through the gate to the unknown.

The Kingdom Within

Tove Meyer dedicated her first collection of poems, Guds Palet (1935; God’s Palette), to the 1890s’ poet Helge Rode, who was still active in the early 1930s and was a keen participant in the contemporary philosophical debate; in her final poems, Hulda Lütken looked back on his religious idealism as a redemptive idea to which she should have listened. Tove Meyer listened, and later also dedicated poems to Helge Rode, whom she considered “a liberated soul. A spiritual sign among stars”.

Tove Meyer’s pen is at work on clear-cut boundaries between life and death, presence and absence – as was her own life, which ended in suicide in 1972. The writer Poul Vad writes of her:

“I think Tove Meyer held onto the words, to the language, for as long as it was still possible for her intellect to extract something new from this material, still to be moved by a form-creating intention. Once she had finished that undertaking, once she had reached the utmost carrying capacity of her voice, there was nothing left for her to do here on earth, and she was utterly overwhelmed by the pain.” “At nå frem. Tanker til Tove Meyers lyrik”

(Getting There. Thoughts on Tove Meyer’s Poetry), Den blå port (2/1985).

In 1969, Tove Meyer’s husband, Paul Nakskov, edited a splendid selection of her poems: Tiden og havet. Digte 1935–67 (Time and Ocean. Poems 1935-67).

The early part of Tove Meyer’s writing career manifests the late-Romantic ambiance, after rain, in autumn, and in spring, and a Romantic platonic interpretation of the poet as the one who, in a world of shadows, can lift the veil to the light, “Aandens Evighedslysen” (The Eternal Light of the Soul), about which Tove Meyer writes in her third collection, Skygger på Jorden (1943; Shadows on the Earth). War and the German occupation of Denmark form an important motif in this collection, and the poet is the one able to talk with “the voice of intensity” to: “Brothers Sisters / all you who murder in order by false gods / to be rewarded.” This long poem actually takes a traditional poetic form in speaking to its contemporary readers of the war, death, murders, and longing for peace, but it ends with a piercing image of the universe of war:

“The shadows of the night

pass through the meadows

even when the sun is at its zenith.”

In Tove Meyer’s works this paradoxicality in the imagery is a distinctive feature that is already noticeable in her early poems. As in the work of Södergran, creative eros involves a death drive that can and must illuminate life. Södergran’s ability to move the poem towards a point of intersection between that which is and that which is not can also be seen in Tove Meyer’s writing. In her poems, “Riget indeni” (The Kingdom Within), about which she wrote in one of her early collections, is an absence in the language, a death drive in the creative process:

All your harvest this dusty throng

ready to take wing? Thinking

of nothing touching on nothing, flake

by flake, like frosty snow falling

stealthily shrouding life dustily

shining through the lily-leaf of death. A gust of wind

and the years are gone. All your harvest this

frail throng ready to take wing.

Speaking to you gently

from its watery heart.

– writes Tove Meyer in a poem from her final collection, Brudlinier (1967; Fault Lines), and we recall one of Södergran’s early poems, “Höstens dagar” (The Days of Autumn), Dikter (1916; Eng. tr. Poems), which opens with delight in autumn, restfulness after the summer, and growth, and which ends in the coldness of death and snow. The movement is reversed in Tove Meyer’s poem, but the two writers share a poetic awareness of the intersection between absence and presence.

In the collection Brudlinier, Tove Meyer’s writing career ends in a suite of poems addressed to a ‘you’. This ‘you’ is not the coveted male ‘you’ or the divine power, “the true male”, as in the work of Bodil Bech and Hulda Lütken. The ‘you’ has become the poetry itself, the poem that originates in the body of the ‘I’:

Never were you crafted in my mind, but

secretly in these veins overflowing

with time, an appointed tryst drawn

towards the boundaries of life, cells and blood

seven times burnt and yet a shadow

in metalline oscillations between

vision and night, beneath the ashes an ember still

spawning its bronze gleam

over distant crumbling landscapes.

Brudlinier completes a transformation of the ‘you’, which has long been en route in Tove Meyer’s writing. The various meanings of the ‘you’ no longer focus on the image of a male figure or a divine factor, althought these meanings also have a voice in the poems. The ‘you’ becomes the work itself. This transformation of meanings is clear in the poem “Dig ung” (You Young), not least through its references to Edith Södergran’s poems on creation.

At the end of the poem, Tove Meyer writes:

“Long since have you seen these gashes –

the clawmarks of the years in my skin

long since you have been seen

going away from my prison free

with your song

your laughter of iron.”

“My heart of iron wants to sing its song”, wrote Södergran in the poem “Skaparegestalter” (Creator Forms) from Framtidens skugga (1920; Eng. Tr. The Shado w of the Future), and in the poem “Fångenskap” (Captivity) from Landet som icke är, too, the creative iron heart figures as a strong symbol for the eros of art and ego. Tove Meyer’s “the clawmarks of the years in my skin” also refers back to Södergran’s poem “Beslut” (Resolve) from Framtidens skugga, where we read: “Every poem shall be the tearing-up of a poem, / not a poem but clawmarks.”

The late-Romantic universe, by which both Hulda Lütken and Bodil Bech were deeply influenced, has been abandoned in Tove Meyer’s late poetry. She moves in a word-landscape of sight, night, and iron. Tove Meyer’s landmark poetry is a creative deliverance of the inspiration from early-twentieth-century innovative literature.

Søndermarken is a Copenhagen park located next to the city’s zoological gardens.

Anne–Marie Mai

Translated by Gaye Kynoch