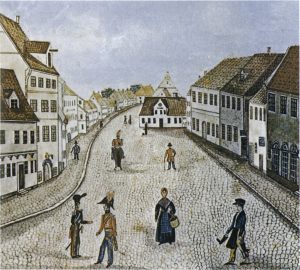

The nineteenth century was the century of reading, and from the outset women – as readers and writers – captured a large part of the rapidly expanding literary market. The book, which had previously been a rarity in the hands of anyone other than theologians, scholars, and the cultural elite, was now, thanks to improved production methods, a commonly accessible cultural ware, and a number of modern media – such as newspapers, journals, and magazines – helped satisfy a seemingly insatiable appetite for the written word. Subscription libraries and book clubs ensured distribution at prices that allowed most people the opportunity to join in the reading. Given that it was the women who had formerly been left out of the (Latin) academic culture, these women now formed the majority of all the new readers.

Readers were particularly enthusiastic about entertaining prose fiction. Of the new varieties now put into production by the media, the main genres were first the fantastical (Gothic) and later the realistic novel. These novels led to a new reading culture, one which initially enjoyed little prestige among the established literary authorities and cultural institutions: the Church, the university, and the theatre, and which was therefore able to develop unhampered by any considerations other than those of market forces – which had no interest in the sex of the author. Women writers had access to the media, if, that is, they could tap into the readers’ desires and needs – and this they could. From the end of the eighteenth century onwards, female authors put their stamp on European popular literature in a manner that literary history has by no means chronicled to any adequate extent.

Fantastical Prose

In the British Isles, whence modern prose fiction spread to the rest of Europe, women authors took an early lead. In 1798, the upper reaches of the bestselling author list at Minerva Press, a publishing house with a long list of popular novels, was entirely female. The preferred genre of these writers was the Gothic novel, the plot of which is usually enacted in aristocratic surroundings, frequently in large rambling houses where innocent young women are subjected to all manner of alarming experiences and outrages committed by demonic men.

It was thus not, on the face of it, by initiating a large audience into the general experiences of women’s lives that the female authors attained success. However, even in the midst of the most fantastical episodes we will often find traces of the middle-class housewife’s standards of decent womanliness, and the tale always closes with an affirmation of good bourgeois morality. The women authors derived advantage from having been kept out of the cultural and educational institutions: they could pick freely from the range of death and sexual fantasies, with their mixture of horror and desire, which authorised Christian philosophy had hitherto held on a tight moral-divine rein, but which the Enlightenment secularisation of the late 1700s had recently set free. Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto (1764) is generally regarded as the starting point for the Gothic genre; however, the two key texts (which were not published by Minerva Press) were written by women: Ann Radcliffe’s The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794) and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818).

Only a limited range of Gothic fiction, sometimes referred to as Gothic horror, reached the Scandinavian readers. The three novels mentioned, by Walpole, Radcliffe, and Shelley respectively, were not translated into Danish during the nineteenth century, and no Danish author rendered the genre in national guise. On the other hand, there were many Gothic features in the texts written by women authors; for example, in Elisabeth Hansen’s Dido og Don Pedro (1821; Dido and Don Pedro) and in Hanne Irgens’s Familien von Heidenforsth (1820-22; The Von Heidensforsth Family). Both these novels are set in a far-away foreign land, and the authors make liberal use of ominous goings-on and demonic gentlemen, murder by poisoning, illicit sexuality, and death, in order to hold the reader’s interest in the fates and sufferings of their heroines. Elisabeth Hansen and Hanne Irgens were among the few Danish female prose writers before the time of Thomasine Gyllembourg who contributed short stories and poems to the many new publications launched in their day.

After a couple of decades, however, the fantastical prose had to give way to a greater degree of realism, but the Gothic features lived on as undercurrents – and not only in the most sensationalist of light reading. Thus, in Sangerinden (1876; The Singer), Louise Biørnsen, who had published her first book – a governess novel – in 1855 and who had gone on to write novels and short stories within the framework of domestic realism, used the Gothic inspiration from the early decades of the century to bind her existential anchor in nineteenth-century women’s Romanticism together with the breach with Romanticism that resulted from the Modern Breakthrough – the demands of which for innovation on the part of writers also affected her work.

Biørnsen’s base in Romanticism comes most clearly to light in her heroines: she can only achieve a stable identity in a love relationship with the man, and she can actually only realise herself in the intimate sphere. The Gothic inspiration behind Sangerinden therefore immediately looms into view when the heroine, Jeanette Dubois, proves to have had a difficult childhood environment. The novel takes the form of an inverted ‘bildungs’ project, the aim of which is to reach the (childhood) home and the intimate sphere she has always missed. Jeanette is French, her father is a musician, and her prematurely deceased mother has been replaced by a lady publican who exploits her stepchildren for business purposes. Jeanette is made to sing in the taproom and is later sold to a circus manager who forces her to walk the tightrope wearing a skimpy costume. She is very unhappy about this degradation, and with her brother’s help, she manages to run away. Her escape is made by means of a dramatic gallop on horseback from the circus ring to the railway station, where the change of transport from horse to train symbolises the entire novel’s stylistic clash between a Romantic identity and a modern society ruled by power and money: “The snorting horse was reined in for a minute, my brother lifted me up, seated me in front of him, and without exchanging a word we raced off at tremendous speed as if all the evil forces in the world were in pursuit. Our ride took us to a nearby railway station.”

Biørnsen’s inspiration, despite its seemingly modern setting, had its roots back in the early 1800s. The heroine has thus borrowed features from Goethe’s Mignon in Wilhelm Meisters Lehrjahre (1795-96; Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship) – the ghastly baroness even calls her Mignon.

Jeanette’s attempt to forge a singing career gets off to a promising start, but she soon falls into the clutches of a seedy baroness, who lures her to Berlin under the pretext of making sure she gets music lessons and as protection from a French Count. It turns out that the baroness’s home is actually a brothel in disguise, with cabaret singers on stage, sexual liaisons in the surrounding booths, and a troupe of resident ‘girls’ to wait on the guests. Nearly one quarter of the novel takes place in this house where, from boudoir to salon, lustful men and avaricious women continually threaten Jeanette’s virtue. She has been forbidden to wander freely around the house, and she is far too innocent to detect its shady goings-on: “Had she read the light French novels and thereby become acquainted with all the frivolousness and immorality which is even found up in the highest circles, then she would long since have understood the Count’s intentions,” comments the author, and in so doing reveals the source of her knowledge about German barons, French counts, and Berlin houses of ill repute – she who lived a quiet spinster’s life in the bosom of her family. Perhaps Biørnsen thought this daring theme put her in tune with the times, but she was actually spinning on the thread from the most popular reading of her youth. In the second half of the novel, she returns to her original genre: the governess novel. Jeanette becomes a lady’s companion and, following many a humiliation, she marries a musician; now she can mind the intimate sphere while he is minding the music: “[…] your best songs belong to me and home,” as her husband states in conclusion.

The Gothic novel allowed the imagination wide scope in which to roam. In the company of its heroines, the female reader could travel much further around the exotic landscapes of European geography and class society than her middle-class intimate sphere would otherwise permit. The genre can be regarded as a female counterpart to the typical male picaresque novel. In both these types of novel, the narrative prose pours over and dives into every possible space where something unknown and strange, and therefore fascinating and entertaining, might be lurking; searching the cubby-holes, corridors, cellars, and closets of old properties was also a voyage of discovery in the labyrinth of the mind.

In Biørnsen’s novel, the heroine’s expedition of discovery relates to the societal fate of female sexuality. Jeanette, in reality an orphan, cannot make her way in life if she does not receive help from the men who own and are in charge of everything. She must therefore constantly endeavour to make an impression on them, while also keeping their advances at arm’s length. All men, however, prove to have an ominous inner lust behind the outer mask of helpfulness, and she never knows which of the two expressions she will see next time they meet. This exposure of the woman’s role, which is described as beset with both pleasure and anxiety, was part of the Gothic novel’s fascination for its female readers.

In Rinna Hauch’s (1811-1896) slim oeuvre – two novels, one short story and a couple of romances – her debut novel, Tyrolerfamilien (1840; The Tyrolean Family), is an interesting example of how faintly Gothic features can merge into a picaresque sequence of events. While living a browbeaten and lonely existence under the harsh domestic regime of her stepmother, Marie meets a Tyrolean family visiting Copenhagen to give a concert. She then leaves home and sets out on a journey through Europe to find this Tyrolean family. A large proportion of the story is spent describing her travels on foot over heath and mountain, alone, poor, unprotected, and vulnerable to financial swindle and sexual assault by coachmen and inn guests. She succeeds in marrying one of her Tyroleans, but thereafter dies of grief a few days after he has perished in an accident. Hauch had overstepped her genre – domestic realism – by setting Marie’s journey in the open air. A Romantic love-death was thus the only possible ending.

Ian Watt did not include the Gothic novel in his classic study The Rise of the Novel (1957). This has inspired feminist literary analysts, such as Rosemary Jackson in Fantasy: the Literature of Subversion (1981), to regard Gothic prose as a subversive genre: the villains are the patriarchal authorities, the women are repressed by them, and the fantastical elements of the text go beyond the bourgeois system of order.

Family Reading

In the opinion of those sections of society traditionally associated with the conventions of a theological and literary education, the penny dreadfuls (sensational fiction for a penny) published by Minerva Press and other publishing houses were synonymous with cheap and vulgar entertainment. The early nineteenth century saw what was virtually a public outbreak of moral panic concerning uncontrolled reading of fiction. Critics attempted to place the blame for disastrously low standards of prose fiction at the door of the many women authors. It was not until around 1840, when the novels of Walter Scott and Charles Dickens had captured the market that criticism subsided, and conventions of formal realism in a contemporaneous setting were accepted as the genre of the culture-bearing bourgeoisie.

The female authors often concealed their bourgeois existence behind a pseudonym, but pseudonyms could easily indicate the correct gender, and in this way women and popular fiction were linked in the readers’ minds. This caused male writers to assume female pseudonyms in order to emulate the women’s success.

During the early decades of the century, the Scandinavian translation market was still dominated by German literature; August Lafontaine’s sentimental-moral novels and Christian August Vulpius’s robber novels were the favourites. The picture, however, changed in the 1820s. The traditionally close affiliation between Danish and German culture was disrupted by the import of wares from the British Isles, with Walter Scott’s historical novels and Charles Dickens’s contemporary novels taking the lead. After the 1840s, the French novel also gained a foothold, with translations of works by Eugène Sue and Alexandre Dumas (père). Both Sue and Dumas based their successful prose production on the mixture of Gothic, historical, and contemporary realism that satisfied the broadest spectrum of readers. The list of writers most frequently translated into Danish during the nineteenth century has Dumas and Dickens in first and second places with 280 and 219 publications, respectively, while Sue and Scott occupy fourth and fifth places with 170 and 164 publications, respectively. Third place is taken by Swedish Emilie Flygare-Carlén with 182 publications. Overall, the list proves that throughout the century women were able to maintain the strong position they had won at an early stage. Of the twenty-five most frequently translated writers, eight – close to a third – were women. Flygare-Carlén was followed by another Swedish author, Marie Sophie Schwartz (1819-1894), with 145 publications, and then the women writing in English and in German shared the market between them.

Marie Sophie Schwartz (1819-1894) was the most-read woman writer in Sweden in the nineteenth century. She published her first work in 1851 under the pseudonym Fru M.S.S.*** (Mrs M.S.S.***), and published a book a year up until her husband’s death in 1858, subsequently between two and five books annually. Most of her work comprised romanticised, socially concerned family novels. The secret behind her huge popular appeal was probably that her works, albeit providing a very frank picture of the gender and class conflicts of the day, always ended under the sign of acquiescence. She was thus an author who could safely be recommended as reading for young women.

The French writer George Sand can be found at number twenty-two with 54 publications; in Denmark she was nonetheless the top foreign female author when it came to securing a place both on the bestseller list and afterwards in the history of literary accomplishment. Thomasine Gyllembourg, who achieved the same feat, was the most frequently published Danish female writer of the century, with 59 publications.

Among Gyllembourg’s domestic rivals was Carit Etlar, the top-selling author with 147 publications; his robber novel from the 1675-79 war between Denmark and Sweden, Gøngehøvdingen (1853; The Gønge Chief [alias Svend Poulsen Gønge]), about the fight of good and honest Danes against the occupying Swedish forces has remained popular reading until the present day. The historical novels of hymn writer B. S. Ingemann saw him achieve 143 publications, while Hans Christian Andersen achieved 86.

Of the English-language authoresses, the early Gothic writers were too exotic for the Scandinavian market. The next generation of writers, however, targeted a specific readership – the family – and these books appealed to the public in general. Criticism of the aesthetics and, in particular, the morality reflected in the burgeoning light-reading market motivated publishers and editors to launch serial publications and magazines attuned to the needs of the family. Advertisements for these publications promised that no parent need think twice before giving them to their daughters.

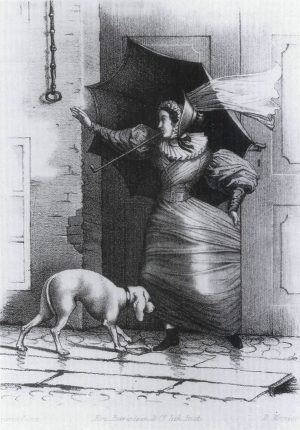

In Denmark, J. E. Wegener published the magazine Huusvennen. Underholdninger i Familiekredse (1818-27; Friend of the Family. Entertainment in the Family Circle), which advertised that it would print “suitable reading” for those “family communities who love the delightful practice of lending an ear to entertaining words, while diligent hands are engaged in constructive pursuits”. In Sweden, L. J. Hierta launched a “Läse-Bibliothek” (Reader’s Library – a series of translated novels) in 1833 and a so-called Familjbibliothek (Family Library) in 1842, although the latter was particularly concerned with non-fiction works on history and social conditions. These family-orientated publication series succeeded the previous century’s gender- or generation-orientated series for “the fair sex” or “the young”.

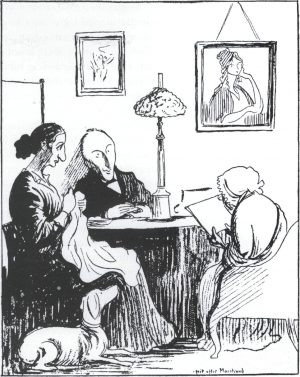

Reading aloud had always been a common pastime at social gatherings. It was usual to share the experience of reading with others, and the quiet, solitary life of an individual with a book in hand was rare. In the mid-nineteenth century, this convention of reading in company was supplemented with widespread reading in the family circle; the nuclear family gathered around the drawing-room table, on which there was a greatly improved style of lamp – and thus reading without daylight was now an attractive proposition. It was this family circle that the publishers wanted to reach with their serialised fiction.

In the Fibiger family, the eldest brother, Adolf, read aloud to his mother and younger siblings in the evenings; his niece, Margrethe, tells us that he “revived the old familiar delights and acquainted them with the best of what the, in a literary respect, so golden days of the thirties had produced”. Louise Biørnsen’s mother, who was prematurely widowed, undertook the education of her nine children herself; one of the methods she employed was reading fiction aloud, and this was to prove the foundation for her daughter’s future literary activities. Rinna Hauch grew up with access to a large library, which she could explore at will. As was the case for women of the Romantic movement in general, reading fiction at home formed the nucleus of their intellectual education.

Thomasine Gyllembourg’s ‘everyday stories’ were also family reading. Johanne Luise Heiberg records how her mother-in-law first read the stories aloud in the evening to Heiberg and herself. They would then be serialised in Heiberg’s journal, Kjøbenhavns flyvende Post (Copenhagen Flying Mail). Although a literary journal, this was also an example of the modern periodical publishing that launched the popular family magazines a few decades later. Heiberg actually established his journal business as a way of making a living for himself. In the second half of the century, Magdalene Thoresen was one of the most frequent contributors to all manner of periodicals, yearbooks, and light-reading magazines – also motivated by bread-and-butter considerations.

In those – not a few – cases where writers and publishers exclusively targeted a family readership, the products were sometimes coloured by moral censorship. The classics were published in versions purged of anything that could be considered offensive; the “Biedermeier” label, which is often applied to the entirety of intimate-sphere-orientated Romanticism, certainly holds true of these sanitised editions. Shakespeare, in particular, suffered; he was admired, but he was also deemed too primitive. Nor did Decameron and the Bible escape the process. Thomas Bowdler’s Family Shakespeare (1807) became a role model for this widespread trend, which was named after its originator: bowdlerisation. In Denmark, the writer Sille Beyer (1803-1861) spent a lifetime expurgating Shakespeare, Calderón, Byron, and Schiller for the stage of the Royal Danish Theatre. She collaborated closely with Heiberg, who was the theatre manager from 1849 to 1856, and Johanne Luise Heiberg, who would be playing the female leads. The revisions of Shakespeare’s plays consisted in simplifying the number of plotlines and amalgamating subordinate characters with leading characters. The aim of the exercise was a practical adaptation to suit facilities at the theatre, which included ensuring such roles for Mrs Heiberg that her talent would be shown to its best advantage. At the same time, however, Sille Beyer also undertook a more problematic retouching in the name of propriety. The English-language original stating that the heroine (in All’s Well That Ends Well, performed 1850) must be able to show “a child begotten of thy body that I am father to” before the hero will marry her, was too much for the Copenhagen theatre audience; Beyer simply deleted passages of this nature.

Sille Beyer’s adaptations provoked sharply divided opinions from her contemporaries. Her fellow writer Meïr Aron Goldschmidt praised them: “In the wild grove, a solicitous gardener has cut away, tied back, and planted flowers, and we feel gratified wonder at the effect this has had,” he wrote in the political journal Nord og Syd (North and South) in 1849. Others, including Georg Brandes, deplored them as corruptions of the great poets.

“The good old lady went about her work with the best of intentions […] ‘By the azure of my stockings,’ she declared, ‘I’ll adapt these personages to modern dramatic requirements.’ And then she brought out a whole sack of fig leaves, and wherever Shakespeare had left the nude, she laid a fig leaf,” wrote Georg Brandes in 1868, in Illustreret Tidende (Illustrated News).

The audience, in the meantime, flocked to the theatre, and it was without a doubt due to Sille Beyer that from 1847 to 1875 five Shakespeare productions clocked up a total of 160 performances. Sille Beyer wrote five plays – comedy and drama – of her own, of which the singspiel Ingolf og Valgerd (1841; Ingolf and Velgerd) took its theme from the Icelandic sagas. She contributed to annual publications such as Molbech’s Julegave for Børn (1835-39; Christmas Gift for Children), and published an anthology of texts by women writers, Vintergrønt (1852; Wintergreen) – the first collection of Danish women’s literature.

In 1853, as a comment to the 1851 Clara Raphael controversy, Beyer issued Tankebilleder eller kvindelige Situationer (Mental Pictures, or Female Situations), comprising brief prose descriptions from the various ‘ages of woman’. Drawing on her experience from the theatre stage, she constructed her pictures as dialogues between a positive and a negative ‘situation’: the happy wife versus the unhappy wife, and so forth. The final chapter, “Den emanciperede Kvinde” (The Emancipated Woman), argues the case that emancipation should not be reduced to “[p]ermission to sell – without any legal male supervision – butter, candles, or soap”, but that it is a matter of inner development.

At this point, Sille Beyer had her hands full with exciting assignments for the Royal Theatre, and she did not feel troubled by the societal restrictions applied to the woman’s role – albeit she was actually invited to publish all her works, except for the anthology Vintergrønt, anonymously. In 1859, however, when her Shakespeare adaptations had again been subjected to harsh criticism, she stepped forward in her own name and voiced her unequivocal misgiving that the critics found her gender the greatest stumbling block. “At the time, no one knew,” she writes about her first play, “that it was written by a mere woman, otherwise it would undoubtedly have received the same zealous treatment as my later works in order to ‘sweep it aside’.”

“The Honorarium Is Of Course, as You Can Probably Imagine, What Is Most Important to Me”

Once Henriette Hanck (1807-1846) had finished her second novel, En Skribentindes Datter (1842; Daughter of an Authoress), she found herself compelled to ask her old friend, the writer Hans Christian Andersen, to help her find a publisher who would pay her properly. “Dear Andersen!, will you speak with a bookseller about my manuscript? If I do it myself, I hear I will be cheated […] and indeed I cannot deny I would find that a burdensome matter […] The honorarium is of course, as you can probably imagine, what is most important to me.”

Henriette was otherwise familiar with periodical publishing. For many years her grandfather, Christian Iversen, published Fyens Stifts Adresse Avis (a newspaper with advertisements for the island of Funen), popularly known as “Iversens avis” (Iversen’s paper), and it was here that Henriette had her first poems printed in 1831 and 1832. Frequent correspondence with a friend she had known since her young days, Hans Christian Andersen, gave her an insight into his professional writing career, and she often provided the newspaper with news he had written to her from Copenhagen or accounts of his journeys.

In 1842, however, her childhood home in Odense was disbanded. The newspaper was sold. Henriette’s father, schoolmaster Hanck, had died. There were six daughters in the family, of whom three remained single. Being the oldest, and having the most delicate constitution, Henriette moved with her mother to an apartment in Copenhagen. The second daughter, Jane, became a governess. Henriette was too proud to lament her reduced circumstances, but she, of course, felt the pressure of her embarrassing problem regarding a means of support and, like so many others, she was obliged to offer her services as a teacher; in Odense she held classes for young girls, and in Copenhagen she taught German to a few young women. She had undoubtedly had a vague notion of an occupation other than that of private tutor. She got to know Hans Christian Andersen when he, an impoverished fellow native of Odense, had sought out her grandfather Iversen to ask for a letter of introduction to influential people in Copenhagen. Through the letters she and Andersen exchanged during the 1830s, and by means of his sporadic visits to Odense, she had personally been able to follow his route to a position of widely travelled, famous, and well-provided-for author. She was familiar with the works of many woman writers – those of Fredrika Bremer, for example. Hans Christian Andersen met Bremer in 1837 and regularly mentioned her in his letters to Henriette. She was interested in literature; correspondence with Andersen entailed analytical discussions both of his works and other reading matter of the day. An attempt to make literature a paying job therefore seemed an obvious idea.

In 1838 Hanck published her first novel, Tante Anna (Aunt Anna). Measured in terms of literary prowess, it has a limited range – as if the pen is being tested out – and it follows firmly in the footsteps of tradition. When Andersen was asked for his comments on the work, he immediately stated his proviso that he did not care for ‘everyday stories’ – “neither Miss Bremer nor pseudo-Heiberg [Thomasine Gyllembourg] have pleased me”. He nonetheless steadily encouraged Henriette to keep on writing, but he also impressed on her the stipulations for success as an author. She had to work faster: “It seems to me you work too slowly, the lyrical therein must still blossom, like a passionflower”; she had to write more: “See to it that you may trump her [Fredrika Bremer]! But then you must be more productive than you are!”; and she had to be able to endure criticism: “Have you the courage to see your best sentiments mocked”.

In 1845, once Hanck had found a German publisher for Tante Anna and had finished her translation of the text, she asked Andersen to write a foreword to the book. Undoubtedly with sales figures in mind, he elected to advertise it as women’s literature from the school of Bremer and Gyllembourg and, moreover, as the first volume of a larger oeuvre. He writes in the foreword: “Having read this Danish authoress, admirers of the Swedish Everyday Stories will certainly be well disposed towards her, and should this not be the case, then her greater work, the story Daughter of an Authoress, will follow.”

The comparison with Gyllembourg and Bremer was quite accurate, given that Hanck’s writing was also ruled by an existential need to express herself, which actually overshadowed the “honorarium”. Her aversion to women writers was no less than Gyllembourg’s: “I seem like a ridiculous woman myself with this scribbling,” she admits to Andersen in connection with her second novel, the working title of which – “Blaastrømpens Datter” (Daughter of the Bluestocking) – in itself discloses Hanck’s ambivalent attitude to her own product.

Henriette Hanck published both her novels anonymously, which did not prevent her trying to crack other writers’ pseudonyms. In a letter dated 17 April 1840, she wrote to Hans Christian Andersen:

“People here maintain that the short story Tyrolean Family is by Fr. Sich, when you hear her language so copiously larded with French and Latin words it is impossible to credit her with writing such pure Danish, I think that is what is striking in this short story, which it seems has been a success in the capital.”

En Skribentindes Datter takes up the whole complex of issues concerning the writing woman: writing as means of expression via which to create identity, as substitute for the ‘real’ woman’s life of wife and mother, and as a livelihood. In the novel, Cecilie’s writing is the result of equal parts inner need and outer necessity. Her family has gone bankrupt, and one of her friends suggests that she could gather together some poems and notes she has long kept in a drawer and sell them for publication. The manuscript she thus embarks upon is called both “a part of her innermost soul, her entire depth breathed it in” and a “dead hoard” that will first be of value when the papers can be turned into money and then into gifts for her impoverished uncle: “Every time Cecilie added a sheet of paper to her yet dead hoard, she recalled one of her uncle’s small necessities of life that he must be missing.”

When her friend arrives with the published work, he presents Cecilie with both the book and the honorarium; she seizes the book, wanting to show it to her uncle immediately, but she finds him struck down by a stroke; her honorarium covers the cost of his funeral.

Hanck thus announces early on that the woman writer’s literary activities destroy those closest to her instead of supporting them. When Cecilie marries actuary Werner, a man who only loves her as a writer, her talent becomes a curse. Her husband is determined to see her as a new Germaine de Staël, and even though her talent cannot live up to it, he continues to make “demands of her muse” and imposes on her the task of writing as a “villeinage”. Cecilie is far happier in the role of mother to her daughter Helene. In the symbiotic togetherness with her child, she experiences an emotional and physical creativity that her strained attitude to writing has never generated.

The theme of the novel is thus the way in which creativity and love address by turns living people and works of art; in other words, the process of sublimation. Until the end of the book, Hanck’s message is that art destroys or is the result of destroyed human relationships. Cecilie’s first poems are the result of a sublimated schoolgirl crush on a French teacher who has abandoned her. Thereafter, she cannot give up art until her daughter is born. Werner has lived through an equivalent development, just in the opposite direction. First he wanted to be a writer, and then he transferred his ambitions onto the person of his wife, who he subsequently felt that he had created: “I alone have guided this budding talent.” Cecilie bears his name, she is her works, which in turn are his spiritual children. The melodramatic final scenes of the novel repeat this conflict between art and human life in Helene’s relationship with her fiancé, the artist Fritz, who has his head turned by a coquettish beauty who poses for his paintings.

The counter-image of false relationships that allow art to intrude upon the most intimate human relations is found in Cecilie’s love for Helene. When Helene splits up from Fritz, she does so in order to live wholly for her mother. “‘Mother,’ replied Helene in a faint voice, ‘now I belong to you alone.’” The end of the story, however, casts a patina of scepticism over Hanck’s construct. Helene intervenes in a duel in order to save the faithless object of her love, she receives a fatal wound, and mother and daughter breathe their last in one another’s arms. The intimate and close mother-daughter relationship, which is the ideological mainstay in the majority of the text, is left looking like a fatally problematic solution, given that art proves to have trespassed here, too. The final scene would appear to be Hanck’s definitive attempt to explode the Pygmalion myth that is fundamentally the theme of the novel: “[Cecilie’s] face rested on that of the dying woman [her daughter], her lips drank in the last breath; she gave it back to the earth.” Hanck is here admitting that the daughter is her mother’s work of art. The life that the mother has breathed into her daughter she now takes back in order to pass it on to the earth. The vicious circle can thus be closed.

Hanck’s analysis of the mother-daughter symbiosis would not come as any surprise to the modern reader with psychoanalysis as intellectual ballast. A reader in the 1840s, however, would have found it extraordinarily impassioned and detailed.

The New Epoch

In the period that followed, the era of the Modern Breakthrough, women managed to retain their strong position in the domain of popular literature. This was, however, principally due to the writers who maintained the social and ideological positions that women’s Romantic literature had won for women. In the work of Johanne Schiørring (1836-1910), who first made a name for herself with Havets Datter (1875; Daughter of the Sea) and later wrote a succession of novels and short stories and for a period was editor of the weekly magazine Vort Hjem (Our Home), and also in the work of Conradine Barner Aagaard (1839-1920), who published a novel every or every other year in the 1870s, the Romantic world picture, with the intimate sphere and love as central values and a mixture of Gothic and everyday realistic elements as stylistic norm, was long the mainstay.

Translated by Gaye Kynoch