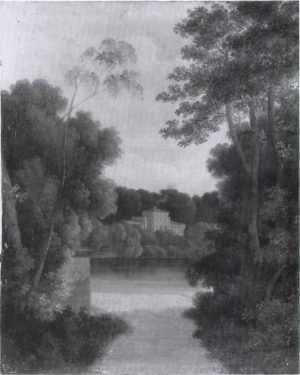

Friederike Brun (1765-1835) presided over her salon for more than forty years. In 1792 her husband, wealthy merchant and Consul to St Petersburg Constantin Brun, purchased the country house known as Sophienholm. Following thorough renovation of the building in Italian style, Friederike Brun opened her summer salon here, her winter salon being held in their mansion in Bredgade in central Copenhagen. Her salons gathered together such famous cultural figures as C. E. F. Weyse, D. F. R. Kuhlau, Jens Baggesen, Adam Oehlenschläger, Just Mathias Thiele, Bertel Thorvaldsen, J. L. Heiberg and many foreign guests. The salon was a sort of open house, in which everyone was received with Friederike Brun’s hearty cordiality. At Sophienholm, guests were invited to stay for days on end and to entertain the hostess, who suffered from profound deafness, as she rode along the avenues of the surrounding park on donkeyback.

The golden age of the salon was during the period from 1810 to 1816. The weekly evening reception was a particularly bustling affair; no one knew how many table settings should be laid until the meal had begun. During dinner, and later in the evening during intervals between music, tableaux vivants, and readings, the guests conducted cultured aesthetic conversation. The entertainment was supplied by visiting artists, and by Friederike’s youngest daughter Ida and the dozen or so young girls with whom she was brought up. The girls took lessons in music, dance, drawing, singing, and tableaux vivants. Ida was the attraction, more so than salon hostess Friederike Brun herself; all the male visitors idolised Ida as the very ideal of art. Following her 1816 marriage to the Austrian diplomat Comte de Bombelles, she travelled around the salons of Europe in her own right.

After 1816 the salon was coloured by Friederike Brun’s anti-French stance, and it eventually turned into a memorial gathering dedicated to a brilliant past, to Ida, and to Friederike’s journeys in Italy. Literary activities and correspondence with friends from the old days, particularly with Caroline von Humboldt, were her lifeline.

Caroline von Humboldt (1766-1829) also had the benefit of an enlightened upbringing with access to learning. She married Wilhelm von Humboldt and went on to enjoy a happy life of shared intellectual pursuits with him and their five children. In the period 1807 to 1810, she and her family lived in Rome, neighbours to Friederike Brun. Caroline von Humboldt held her own very well-patronised salon wherever she was living, from 1810 in Berlin, where Humboldt founded the university.

She was a great correspondent, but left no other written works. Her letters are calm, considered and completely devoid of the sentimental sensitivity current in her day.

Friederike Brun’s father was a German pastor; he took a job in Copenhagen when Friederike was ten weeks old. His position was that of court chaplain. He was a highly esteemed preacher, and he took part in the cultural life of the German Enlightenment circles in Copenhagen. In the 1770s, Friederike attended Royal Physician von Berger’s salon, which was to become an exemplar for her own salon. In her memoirs she wrote:

“Scholars and artists, the princes of the Royal House, and the foreign ambassadors all flowed together here in forming that harmonious whole which alone deserves to be called good society; for this never arises out of the narrow committee of a few privileged classes, but only from the free and comfortable harmony of the important members of all of them.”

Being the apple of her father’s eye, Friederike was brought up as befitted a bel-esprit. In the German milieu, she was considered to be an exceptional child; Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock

In 1750, when he was a young writer of much promise, Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock (1724-1803) was invited to Denmark by Count Bernstorff. Klopstock had published the first three cantos of his religious epic Der Messias (1748) in a German periodical, and was granted an annual pension by the Danish king to complete the work. In 1770 he left Denmark when his patron Bernstorff fell from power and was supplanted by Struensee. Friederike Brun visited Klopstock a number of times at his home in Hamburg, expressing great delight on each occasion.

and Johan Bernhard Basedow

Johann Bernhard Basedow (1724-1790) was called to Denmark at the request of Klopstock, because he had a reputation as a teacher with remarkable and liberal-minded ideas. He is indeed known to posterity as an architect of educational reform, as proposed in Methodenbuch für Väter und Mütter der Familien und Völker (1770; The Method Book for Fathers and Mothers of Families and for Nations) and Elementarwerk (1774; Elementary Work). One example of his method: the baking of alphabet cakes to teach Friederike Brun to read. The project failed, however, due to her great fondness for sweet things.

took an interest in her progress. A yearning back to the promised land of childhood was later to be the driving force both of her salon and her writing. However, this also led her into two pivotal conflicts. As her father’s daughter, Friederike distanced herself from the female role fulfilled by her mother; at the same time, she idealised her mother. She explained her own hysteria and her nervous physical symptoms by maintaining that, as a modern woman, she had distanced herself from her mother’s practical life. As a bel-esprit, she endeavoured in her life, in her works, in the salon, and in Ida’s upbringing, to outline other roles for women, but she never succeeded in getting (back) to that for which she yearned.

The second conflict can be seen in her writings. Friederike Brun wrote from childhood until her death. She published fifteen volumes of miscellaneous works (all originally written in German), of which the early texts in particular were well received. She contributed to periodicals and yearbooks, she exchanged letters, and she kept a diary throughout her life. Continuing the German tradition of sensitivity, from Klopstock to Friedrich von Matthisson, and greatly influenced by Rousseau, she recorded the stirrings of her soul via descriptions of nature and odes to her god. Her writing was so close to that of her role models that she has to be called an imitator. Of reading her landscape descriptions, Oehlenschläger said he would rather be beaten with a cane – and they are indeed long-winded and dry. Now and then, however – in her early output, too – a refreshing new approach emerges; the first example of this is her poem “Til mit ufødte Barn” (To My Unborn Child), in which the pregnant woman’s body and her sensitivity are described in such a way that they can still capture the reader. In the last phase of her writing career, in her works of memoir, the late prose pieces, and especially in her correspondence with Caroline Humboldt, she is straightforward, clear, and amazingly modern. She describes her comfort-eating, her fondness for laudanum, her loneliness, and above all she observes her body with wonder, describing it in specific and highly-detailed terms as a shackle holding her mind captive.

Friederike Brun’s father paid for her first two publications and put pressure on her to marry a wealthy man who could provide for her life in the arts. Constantin Brun had no interest in cultural affairs, but he was a zealous businessman who was willing to pay for the prestige associated with having a wife who was interested in the arts and who had a high public profile. In the early years, their marriage was a happy one. Friederike gave birth to five children during the period 1783 to 1792, and she went on a number of trips, alone or with her husband and children. In 1791 she invited the leading Danish writer Jens Baggesen to travel with her to Pyrmont, where she met the Swiss writer Karl Viktor von Bonstetten (1745-1832).

Jens Baggesen (1764-1826) wrote his version of the journey he made with Friederike Brun to Pyrmont in his major work Labyrinten (1792-93; The Labyrinth, 2 vols.). He was a lifelong and dear friend of the family.

He was to be her fate. She calls Constantin Brun “the man God gave me”, and Bonstetten “the man my heart chose”. In keeping with the Venus Urania philosophy, Bonstetten was for many years her spiritual lover, while her relationship with Constantin Brun gradually became very strained. In 1795, 1796, and 1797 she travelled to Karlsbad, Rome, and Naples with Bonstetten. From 1798 until 1801 Bonstetten lived with the Bruns in Copenhagen; in 1801-1802 he and Friederike were in Geneva, 1802-1803 in Rome. They stayed with Mme de Staël on the Coppet estate from 1805 to 1807, where they were accompanied by Ida, and they were in Rome from 1807 to 1810.

In De l’Allemagne (1810; Germany) Madame de Staël describes Ida and her mother thus: “[…] sculpture in general loses much by the neglect of dancing; the only phenomenon of that art in Germany is Ida Brunn, a young girl whose situation in life precludes her from adopting it as a profession; she has received from nature and from her mother a wonderful talent of representing, by simple attitudes, the most affecting pictures or the most beautiful statues; her dancing is a course of transient chefs–d’œuvre, every one of which we should wish to fix forever: it is true that the mother of Ida had before conceived in her imagination all that her daughter so admirably presents to our eyes […]. I saw the young Ida, when yet a child, represent Althea […] a painter could not have invented anything finer than the picture which she improvised […].”

All these trips were taken for the relief of Friederike Brun’s convulsions and fevers – which always cleared up when she saw the Alps and Rousseau’s home district – and they held a salon in each of the places they visited. In 1810 Constantin Brun insisted that Ida should return home, and he offered Friederike a pension were she to choose Italy and Bonstetten in preference to Denmark. She decided to travel home with Ida, however, certain it would be the death of her. For the rest of her writing life, her letters and diaries were full of lamentation, complaint, and yearning for Bonstetten and Italy.

Living with tension between mind and body, past and present, Bonstetten and Brun, Italy and Denmark, Friederike Brun used her writing and salon to seek harmony. In terms of content, this was achieved in her writing by means of camouflage. Her basic frame of mind is one of depression, tearful, but in such a way that immersion in melancholy turns into euphoria. The volumes of poetry written in 1795, 1812, and 1820 thus, albeit reluctantly, reveal a woman split in two.

This is also true of the nine volumes of travel-diaries and -letters which Friederike Brun published between 1791 and 1818, apart from Briefe aus Rom (1816; Letters from Rome) in which a spontaneity is allowed to shine through the rewritten coating that otherwise veiled the validity of her authentic diaries and letters. It was not until her final work, Römisches Leben I–II (1833; Roman Life I-II), that she completely freed herself from her affected role models and wrote directly and vividly about life as lived by the common people in Rome, about women and children on the streets.

The most fascinating works from her pen are two texts published in one volume in 1824, Wahrheit aus Morgentraumen und Idas ästhetische Entwickelung (Truth from Morning Dreams and Ida’s Aesthetic Development), and later translated into Danish as Ungdoms–Erindringer (1917; Memories of Youth). Here, she does not present herself in the guise of author, but writes like a female individual; the excuse being that she has seen it all in laudanum-induced hallucinations.

In the first section of her work of autobiography, Friederike Brun describes her childhood and early youth as the paradise lost. In the second section she describes Ida’s childhood. The interpretation of her own childhood conjoins the personal expulsion from paradise with a greater cultural fall. Her role model Emilie Schimmelmann dies, she falls hopelessly in love with August Hennings, and her sufferings begin to fuel her writings. These events coincide with the enlightened German cultural elite, of which she was a part, losing its exclusive position. Debate of literary and philosophical matters becomes subordinate to political and economic issues. Women belong to the sphere of the home and culture, men to that of economics and politics – exactly the situation in Friederike Brun’s marriage. While she was presiding over her salon with artistic men and interested women, Constantin Brun would be sitting at the gaming tables in the anterooms or in his club. In Friederike Brun’s account of her young days, this gender polarisation coincided with the onset of menstruation and her finding pleasure in writing. Considering her construction of the personal, the sexual, and the cultural fall, it is hardly surprising that she had to shift her sexual desires to the spiritual sphere. Her body, however, with its nervous symptoms and hysteria, time and again breaks through this armour. In seeking an explanation for the scourge inflicted on women with the new era, she intimates that it is caused by unrequited love, a lack of sexual and personal development; she cannot, however, use these explanations in relation to her own life. To the very last, she is at a loss.

In her self-image, Friederike Brun rejects that which is outdated and affected: fashion, coiffures, babies’ swaddling clothes. She is ‘natural’, allows herself to be moved, but is at the same time dependent on men’s judgement and acceptance. She reveres celebrated men and submits to their opinion. She lives a split life between something female, which is barely defined, and something male, which provokes hysteria and makes for melancholy. This split, which set in with puberty, vanishes with the menopause. It is bound up with the sexual femininity. Post-menopause, however, she feels “hermaphrodite – and at the same time amphibian, neither cold not hot”, as she writes in a letter to Caroline von Humboldt.

Friederike Brun longs to be free of the split existence while she is in it, but longs for it once she has left it. The first part of her writing career therefore seeks out harmony, while the latter part seems more concerned with trying to describe the split existence as personal experience.

In Idas ästhetische Entwickelung, Friederike Brun gives an account of the way in which she brought up her favourite daughter, Ida. Both the book about Ida and Ida herself have to be seen as part of Friederike Brun’s project. In the book, Friederike Brun describes the child Ida from the time of her infancy. Inspired by Rousseau, she sees the child as a collection of innate talents that it is up to the mother to cultivate. The book is a declaration of love to her daughter, a contribution to the child-rearing literature of her day, and a manifestation of the new ideas stemming from the post-Rousseauesque debate regarding qualitative motherhood.

Friederike Brun describes herself as an intuitive and empathetic mother who is quick to detect and support her daughter’s gift for singing, drawing, music, and mime. No doubt Ida had talents – as do most children. This is quite obviously a case of mother projecting her own unrealised ambitions onto daughter – ambitions with regard to becoming a different form of female bel-esprit. Ida learns to be in control of her body – to use the body, not the written word, as her medium of expression, and to express other people’s stories. While her mother wrote in keeping with male artists, Ida plays out the male artists’ tales. Friederike tries to spare her daughter the painful process of forming one’s ‘self’, to which her own memoirs bear witness. That this is not achieved without costs can be seen from Ida’s potentially fatal period of anorexia and her coolness and aloofness in relation to everyone – apart from a young man her mother prevents her from marrying.

Many descriptions of Ida have come down to us via her male contemporaries. They perceive her to be the female ideal: the woman between chrysalis and butterfly – that is, the young woman who never comes out of her cocoon and turns into an adult. Friederike Brun’s picture of her daughter’s upbringing can also be seen in this light. She is the girl curtailed in development. She is woman as pure form. Unlike her mother, she can skilfully cover up her (bodily) discomfort. On the other hand, she cannot express it in writing or speech. Ida was the nineteenth-century ideal of woman par excellence: white marble, graceful, and silent; the muse, ready to receive masculinity’s fantasies about the feminine.

Friederike Brun herself has to be viewed as a transitional figure – just as the whole salon culture is a transitional phenomenon – between a predominantly feudal and a predominantly bourgeois culture. She and her salon manifest a lived utopia of a third way: between feudalism and capitalism, between the female and the male as keenly defined spheres. The salon provided, for a brief period, a forum for contrasts. And in her writing, it is the works that give the stage to the experience of contrasts, the two minds, which come alive. Salon and writings alike live on longing for something else. What they once were – or what has yet to be. This gives both parts a tinge, by turns, of melancholy and euphoria. Perhaps it is this continual movement that makes salon life and parts of Friederike Brun’s literary output seem so fresh and relevant.

Translated by Gaye Kynoch