Thekla Knös (1815-80) was regarded by her contemporaries as a typical exponent of everyday culture, when, approaching her forties, she published some poems that essentially conform to what has been called “the piano lyrics of the professorial home” – a cheerful, pious, and snug – homey – idealism.

The question is, however, how stable this contentment actually was. For in private letters and personal diary entries Thekla Knös expresses, time after time, a strong feeling of unhappiness with her stifling existence as a woman and an equally strong desire for what she calls “real activity”. This is so much more remarkable as Thekla Knös and her mother, Alida, commonly known as ‘the small Knöses’, wrapped up their lives in a playful veil of unreality.

Alida Knös, née Olbers (1786-1855), was married to the theology professor Gustaf Knös (1773-1828). The couple had two daughters, Nanny (1812-19) and Thekla. It was after the death of Gustaf Knös that mother and daughter began to be called “the small Knöses”.

It was to “the little bird’s nest”, as their home was called, that people – that is Gunnar Wennerberg, Curry Treffenberg, and others

Gunnar Wennerberg (1817-1901) studied in Uppsala and was the creator of Gluntarna (The Boon Companions), a very popular collection of students’ songs.

Curry Treffenberg (1825-97) studied in Uppsala and is notorious for, as a county governor, having had the Sundsvall strike of 1879 suppressed by force of arms.

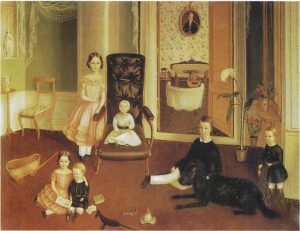

– went after having been at Malla Silfverstolpe’s listening to her and to the, at this point, highly respected gentlemen Erik Gustaf Geijer, P. D. A. Atterbom, and their like. Malla’s salon was a serious matter, but at Thekla and Alida Knös’s people played charade, sang, and instituted an Order of the Pimpernel (‘Pimpinellaorden’), inspired by Carl Michael Bellman, albeit cuter and more idyllic. The doll’s house atmosphere is totally overwhelming in Thekla’s own later description: “Our little home with its simplicity and its air of poetry, the small pearl-coloured sofas, the tiny children’s chairs, and the small dishes, as well as our obliging maid Lovisa, who would call out: ‘now go and sit down’, when the table was set”.

Actually, the home was not just any doll’s house but an exotic ‘growing castle’ that stood out distinctly from the period’s middle-class homes. The furniture was upholstered in embroidered Chinese silk; the walls and parts of the furnishing were covered with plants that normally belong in the wild and in the garden: ivy, jasmine, lilies. As the years went by, Alida and Thekla Knös began to treat and regard their plants more and more as living beings with a developed emotional life of their own. For example, they would never show themselves undressed in the presence of the lily, out of respect for its particular innocence.

“The small dishes” were simple. Often only tea was offered – after the death of Professor Knös the home was poor – but with the aid of fantasy a bit of eau de cologne in a bowl could turn into incense and myrrh. At the institution of the Order of the Pimpernel, which was attended by Grand Master Alida, Grand Master Gunnar Wennerberg, Mistress of Ceremonies Thekla, as well as the Honorary Members Prince Ferdinand (the Knöses’ cat) and Miranda (the Knöses’ bird), a couple of bottles of Liebfraumilch, donated by Baron von Kræmer, and some pastry, baked by Malla Silfverstolpe, were transformed into red wine and newly-shot snipe, in the manner of Bellman.

There was something bizarre about this home that throws an ambivalent light over the idealised sweetness which contemporaries ascribed to ‘the small Knöses’. The Romantic period’s cultivation of nature and fantasy moves into the ideal late-Romantic middle-class home and threatens to burst its walls from inside. A corresponding ambivalence is found in Thekla Knös’s poems, although at first sight they seem conventional and typical of the period. Several of them may be and have been characterised as nursery rhymes. “Baka, baka liten kaka” (Bake, bake a little cake) is one of the first rhymes that each and every Swedish child learns – clearly without knowing that Thekla Knös wrote it.

Several of Thekla Knös’s poems were set to music and circulated in copies in Uppsala, until Atterbom succeeded in persuading Thekla to have them published. In the preface to the volume he had published in 1852, he pays tribute to the “simplicity” of her poems – a positive word in the context of the literary climate at the time. The collection of poems includes a great variety of the most popular types of poems in the late-Romantic period, that is, the genre piece and the role poem.

The genre pieces often depicted simple human beings, elderly people, widows, children, farmers working, etc., and this was also the case with Thekla Knös’s contributions to the genre. She prefers to concentrate on the kitchen, and it is primarily children that she describes in her ‘idylls’. Titles like “Syltningsvisa” (The Jam-Making Song), “Bakningsvisa” (The Baking Song), and “Strykningsvisa” (The Ironing Song) are representative of her choices of subject. Her models are Frans Michael Franzén, Erik Gustaf Geijer, and Johan Ludvig Runeberg, the three guiding stars to a whole generation of poet followers, who paid tribute to the simple, natural, and idyllic. But already at that time attention was also called to such foremothers as Anna Maria Lenngren and Euphrosyne. On the whole, Thekla Knös’s poetry is one of many testimonies to the fact that the middle-class Realist lyric poetry of the late eighteenth century was never completely silenced by the sweet-scented language of Romanticism, nor by the blaring trumpets of Esaias Tegnér and his followers. After High Romanticism had vanished, there was renewed interest in Lenngren, Franzén, and others. However, at that point it was not so much Lenngren the herald of Enlightenment who began to be appreciated, but Lenngren the portrait painter, the Realist, the idyllist, and the keen-eyed observer.

Thekla Knös alludes to Anna Maria Lenngren’s famous poem “Thé-Conseilen” (1777; The Tea Council), when in “Kaffebjudningen” (The Coffee Party) she satirically describes how “neat, prim / ladies mince about”. But the tone immediately changes into a flaming appeal when she focuses on the poor girls, who are bored to death but have to attend the coffee party, while their male friends and contemporaries revel in the spring sun, with banners and song, in “merry bands of youth”.

The contemporary literary critics commended the poems of Thekla Knös and saw in her lyric poetry a confirmation of the thesis that the ‘historical period of art’ had ended. This did not mean that the poem, or poetry, had had its day, but that it had been given a new function, namely to embellish everyday life. Accordingly, the field of poetry was opened up to the female poet as well, for it had already for a long time been the woman’s task to embellish the ‘real’ everyday life. The “simplicity and purity of feeling” that the critics believed they had found in Thekla Knös fit these theories like a glove.

However, when she published an attempt at one of the more demanding and male genres of the period, Ragnar Lodbrok. Skaldestycke (Ragnar Lodbrok. A Poem), an epic poem with an Old Norse topic in the style of Tegnér’s Frithiofs saga (The Saga of Frithiof), the critics were not as gracious, despite the fact that the poem was awarded a prize by the Swedish Academy – she fits better “into the world of the home” and therefore should have remained there.

Nonetheless, Thekla Knös’s long epic poem about Ragnar Lodbrok is in many ways quite a female and homespun variation on the heroic epos. It can also be seen as a literary reply to Frithiofs saga. We seldom meet her Ragnar Lodbrok on the battlefield, however. Instead, where we see him is at home and in various romantic situations. The latter was in itself typical of the epic poems of the 1830s and 1840s, which showed more interest in the hero’s love affairs than in his martial exploits, but a hero with a child to take care of was, after all, something that had not been seen before. Ragnar Lodbrok is interesting in so far as it bursts the boundaries of its own genre and points ahead to the psychological novel. Whereas older epic poetry had placed the protagonist in a situation involving a conflict between honour (the duty towards king and country) and individual happiness (love), Knös uses two different episodes taken from the Old Norse sagas about Ragnar Lodbrok and combines these in a kind of versified novel of marriage, which includes falling in love, building up a family, family crisis, and reconciliation. The latter is brought about with the children as a mediating and reconciling bond. The family comes out victorious.

Thekla Knös’s interest in children is striking. Not only does she write about children, she also writes for children, and her career as a female author is thus typical of the period. Many female authors began their career by writing calendar poetry, maybe a prose story or two, turning gradually thereafter to children’s books. It needs to be mentioned that Thekla Knös, like many other female writers of the period, did not have children of her own. Instead, she describes her poems as her children. When finally she consents to publish them, she is worried about how her ‘children’ will fare in the world. In other contexts, she plays the part of the child herself; her doll’s house life is an example of this.

Children’s poetry, children’s love poetry, children’s idyllic life, and the ideal child – these were genres and topics that suited the taste of the time, and they may have seemed to be ways out for women in the unquestionably suffocating atmosphere of the parlour culture. But it is also in this context, with regard to that which most corresponds to the taste and demands of the period, that Thekla Knös’s ambivalence becomes evident. Following the example of Atterbom, she wrote many poems about flowers – “Rosorna” (The Roses), for example – but whereas Atterbom uses the plants as symbols of human ‘individuations’, the border between human beings and nature is more elusive in Knös’s writings. In her poems, it is sometimes the soul of the flower that can be observed in the human being, and not the reverse.

In some of her role poems she oversteps the limits of what was then suitable, of “the simplicity and purity of feeling”. Nowadays, when nearly all poetry involves an intimate lyrical ‘I’, role poetry is an almost unknown genre, and we often make the mistake of reading the role poems of older periods as if the poetic ‘I’ were identical with the author. But this was still inconceivable in the middle of the nineteenth century. If one opens a literary calendar from the 1830s, one is certain to come across at least one poem entitled “Brottslingen” (The Felon) and another entitled “Främlingen” (The Stranger). These were popular types, which each and every poet, even the most law-abiding and the greatest homebody, was to bring to life in the form of a monologue. Geijer’s “Vikingen” (The Viking) and “Odalbonden” (The Freeholder) belong to this genre. Therefore, one obviously has to avoid reading too much of the author’s feelings into those of the poetic ‘I’. Nevertheless, it is interesting that so many of Thekla Knös’s contributions to the genre involve a man looking at a woman. One of these poems, “Kan en mygga besjungas?” (Can One Sing the Praises of a Mosquito?), was sufficiently ambiguous to arouse the indignation of contemporary critics. In the poem, the ‘I’, a young man, is peeping at a girl working in the kitchen. Her sweaty hairline and her bare neck and arms are described, and the ‘I’ becomes jealous of a mosquito that is sucking her blood. There are not many poems in the two collections by Thekla Knös that exhibit such ambiguity, but in the papers she left behind there are indications that she destroyed a number of ‘inappropriate’ poems before she vanished to the place where so many creative and frustrated women formerly ended their lives, the asylum.

Thekla Knös’s toying with gender roles, her deliberately ironic fusion of poetry and everyday prose, and her addressing an audience consisting of children and adults are characteristics that point in many directions. Anna Maria Lenngren and Fredrika Bremer are brought to mind in poems where ‘composing a review’ is described as choosing “some eggs of the kind / that would teach the hen to lay”. Children’s poetry and role poetry easily make one think of Hans Christian Andersen: they reveal the fact that there might be a need to conceal one’s gender and to burst the walls of the parlour.

Translated by Pernille Harsting