Magdalena Sofia, ‘Malla’, Silfverstolpe, née Montgomery (1782-1861), holds an assured, albeit peripheral, place in the history of Swedish literature as the hostess of a salon in Uppsala in the period of Romanticism. She hosted the most well-known learned salon in Sweden, frequented during the 1820s and 1830s by, among others, the authors Erik Gustaf Geijer, P. D. A. Atterbom, and C. J. L. Almqvist, and the musician and song-writer Adolf Fredrik Lindblad. Through her contact with these famous men Malla Silfverstolpe has gone down in history, whereas her own person and her individual contributions to the salon culture have been marginalised. Her great memoirs, published posthumously in four volumes in 1908-11, are at one and the same time the most important document about the Swedish salon culture and the most interesting literary text by a woman that has issued from this cultural milieu. This latter dimension has been neglected, and the work has primarily been highlighted as a historical source of knowledge about the period’s famous men.

Malla Silfverstolpe’s whole life is intimately connected with the salon culture. It can be described as a movement from one kind of salon culture to another, with her childhood and youth in the salon milieus of the aristocracy serving as a social, cultural, and personal preparation for her later ‘career’ as the hostess par excellence in the more middle-class academic and literary environment in Uppsala.

Malla Silfverstolpe was born in Finland, but she came to Sweden at a very young age and grew up at the Edsberg Manor outside of Stockholm with her maternal grandmother, Baroness Magdalena Rudbeck. Her mother, Charlotte Rudbeck-Arnell died just after Malla’s birth, and her father, Colonel Robert Montgomery, also disappeared from her life at an early point. Malla Silfverstolpe’s family was critical of the absolutism of King Gustav III, and after having participated in the so-called Mutiny of Anjala during the war with Russia, her father was first condemned to death and afterwards exiled to the then Swedish West-Indian island of St. Barthélemy. He returned from exile in 1793 and died in 1798.

In her Memoarer (Memoirs), Malla Silfverstolpe’s childhood at Edsberg comes across as a life amid a crowd of people combined with the feeling of emotional isolation. The grandmother is her primary parent figure, but Malla also sought the company of a circle of younger relatives and friends, who meant a lot to her. Together with them she developed what today we would call a youth culture, influenced by the aristocratic salon milieu. The circle is interested in politics and culture and inspired by the ideal of liberty and the pre-Romantic atmosphere of the later eighteenth century. They greatly admire the heroes of the French Revolution and the American War of Independence; they read and put on plays; and they develop, inspired by Goethe and Rousseau, a cult of love and friendship, in which confidentiality, intimacy, and soul relationships are fundamental elements.

The literary salon in Uppsala is described in the Memoarer as Malla Silfverstolpe’s second circle, which she creates for herself at a mature age when the circle of her youth has been scattered and their patterns of life have been lost. What is more, the salon appears to be an alternative to married life: when she creates the salon, Malla is thirty-eight years old and recently widowed after twelve years of childless marriage to Colonel David Gudmund Silfverstolpe, a marriage in which she “so to speak stifled herself in order to be able to survive in the tiny bit of breathing space that she had been granted”.

It can be argued that by discovering an identity in her function as a hostess, Malla Silfverstolpe makes friendship and love into a form of life without having to submit herself to the limitations that marriage might involve. The Uppsala circle serves as an alternative family in so far as it provides her with security and intimacy. Moreover, it offers her the possibility to live out some of the more self-assertive and romantic features from the milieu of her youth.

The presence of middle-class, intimate features in the salon culture of Uppsala is confirmed both by Malla Silfverstolpe’s Memoarer and by other descriptions from the period written by, for example, Thekla Knös. Together with the Geijer and Knös families, Malla Silfverstolpe constituted the centre of social life in Uppsala in the Romantic period, and their contact was not limited to the gatherings at the salon but also involved getting together on a practically daily basis. They exchanged letters and had many long conversations; they celebrated each other’s birthdays and anniversaries, for example with excursions to the countryside where they would stage mythological tableaux vivants and enjoy wild strawberries and wine. It is the intimate side of the salon culture that Malla Silfverstolpe herself emphasises when, in her Memoarer, she describes her initiative of creating the salon:

“In order not to be waiting in vain for visits and still have the pleasure of seeing one’s friends now and then without expressly inviting them […], she announced […] that she would be at home every Friday evening and would gratefully receive those who might be thinking of her then. Malla chose this day for the sake of Geijer, who would then have finished his lectures for the week and had two free days ahead of him.”

The reader should not, however, be misled by the humble tone here. For it is apparent, both from other parts of the Memoarer and from other sources, that Malla Silfverstolpe’s salon was a genuine learned salon and not a usual middle-class parlour. Her ‘Fridays’ enjoyed a high status, were not open to everyone, and involved certain formalised literary and musical activities. There, authors tested their works before offering them to a wider audience – Atterbom, for example, read aloud his Lycksalighetens ö (The Isle of Bliss) – and there, artists of a younger generation, for example Adolf Fredrik Lindblad, took their first steps towards fame.

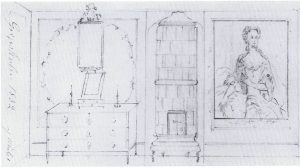

The formal aspect of Malla Silfverstolpe’s salon is also expressed in a spatial manner. The social activities took place around a tea table and a grand piano in a big and “well-lit” room, whereas the more private contacts in pairs or in smaller groups took place in the little “dim cabinet that had witnessed so many acts of confidence”.

From Anna Hamilton Geete, I solnedgången. Minnen och bilder från Erik Gustaf Geijers senaste lefnadsår (1910-14; At Sunset. Memories and Images from Erik Gustaf Geijer’s Final Years).

In the 1820s, when Malla Silfverstolpe’s salon was at its most active, Uppsala was a national centre of the culture and learning of Romanticism. Malla’s salon was the heart of this culture’s social life. The role as a celebrated hostess surrounded by famous men gave her not only status but also erotic possibilities: her roles as muse, benefactress, and mature adviser to the circle’s young men resulted in a number of romantic relationships. In this way she violated the moral codes of the group, however, and subjected herself to both criticism and ridicule. The only person who appears to have been sympathetic towards her in this respect was, interestingly enough, Bettina von Arnim, whom she had met during her journey to Germany in 1825.

In Efterlemnade anteckningar (1881; Posthumous Notes), Thekla Knös describes Malla Silfverstolpe as a hostess:

“In her home and in the lively light of her eyes many a bashful poetical nature blossomed, and many a hitherto unappreciated musical genius was lured out of the shadow by her kind questions. Each and everyone felt happy, for she enticed hidden treasures by means of interesting conversations as though through a divining rod.”

Owing to her romantic affairs, Malla Silfverstolpe came into conflict with the traditional Romantic middle-class view of women, which was characteristic of the salon circle in Uppsala. The woman was idealised as the good genius of the man, as his muse, but at the same time she was expected to be humble, self-sacrificing, and not erotic. This view of women fit several of the salon hostesses in Uppsala well, for example Agnes Geijer-Hamilton and Thekla Knös, but on account of her aristocratic background, her widowhood, and her economic independence, Malla Silfverstolpe appears to have been able to create for herself a more expansive role as a hostess. Nevertheless, like the other salons, her salon is male dominated, both as regards artistic and intellectual accomplishments. It is not her own writing or intellectual brilliance that made her the most popular hostess in her circle. Rather, it is her ability to create an exciting atmosphere and environment that is emphasised in descriptions from the period. She appears to have possessed a decidedly receptive mind with a great capacity to listen, to show enthusiasm for other people’s ideas, and to make people open up and feel appreciated.

Malla Silfverstolpe’s cultural interests were considerable, and since her youth she had followed the developments in English, French, and German literature, but what appears to have particularly engaged her is the combination of life and fiction: the idea of culture as pleasure and conviviality. “Music, song, rich conversations – wonderfully entertaining, the way I wish it would always be”, she writes in a typical remark after one of her first meetings with the prospective salon circle. It is also the dialogical and socialising cultural aspects of the salon – the conversation, the letter writing, the reading aloud – that especially appeal to her. On the issue of reading aloud she writes: “What she read on her own and silently, she did not understand too well; everything collective, shared with others, was to her a double joy.” And socialising became particularly pleasant when it was intensified by a romance, as in the beginning of the 1820s when Malla Silfverstolpe was attracted to the young Per Ulrik Kernell and “at every beautiful thought that was read aloud was […] certain to meet the eyes of the attractive Kernell”.

Since it is the salon culture as a form of life that fascinates Malla Silfverstolpe, in her memoirs she does not pay much attention to the various cultural activities as such. Often she is content with saying that there had been music, song, and conversation. Now and then she notes down the kind of music or literature involved, but she hardly ever writes about the contents of the conversations – she is especially taciturn when they deal with philosophical or political issues. However, the reader almost always hears about the emotional effect the activities had on her, whether they made her happy or sad, or whether she felt empty or elated. We also learn about her views of the persons belonging to the salon circle: what she thought about their characters and how their experiences with for example love or marriage differ from or correspond with her own. It is, in other words, emotion, the private sphere, and the existential questions that are at the centre of her cultural interest in the Memoarer.

In her essay “Malla och hennes värld” (1912; Malla and Her World), the critic Klara Johanson calls attention to the fact that it was by virtue of her “heart” that Malla Silfverstolpe created a place for herself in the circle of the Romantics. A Romanticist herself, she was in fact more daring than the authors around her, in so far as she tried to implement the ideas of Romanticism in her own life. As Klara Johanson puts it, Malla “set out on a quest for the isle of bliss, which they in their homely complacency merely prophesied about”.

Writing and Life

Malla Silfverstolpe’s memoirs, which she herself called Minnen (Memories), involve several different types of texts and have a long history of composition. The main text is an elaboration of her diaries and letters, written in the third person, and at a later point interwoven with a running diary, written in the first person, and with letters by herself and others. The memoirs were begun in 1822 and completed in a first version in 1836, to be reworked in the 1840s. The further elaboration, which took place in connection with the publication in 1908-11, is the work of Adolf Fredrik Lindblad’s daughter, Malla Grandinson.

The reasons that Malla Silfverstolpe gives for writing the memoirs vary; for example, she mentions her “need for clarity” and that the memoirs may serve as a “warning and admonition to others”. Ultimately, however, the text appears to be the result of a search for identity: through her writing she seems to want to give a clear form and shape to herself and her life. That she is inspired by existential concerns emerges also from the fact that the writing process got started during various crises in her life. In 1808, when as a newly-wed she has left her childhood home, she begins for the first time to edit her diaries, but her writing of the memoirs does not really take off until the beginning of the 1820s in connection with her falling in love with Kernell, her most serious romance with anybody belonging to the salon circle.

Malla Silfverstolpe singles out Kernell as her source of inspiration and her special reader. In the memoirs she writes that Kernell had wanted her to “write down for him her memories from her childhood and youth”. However, it is actually she who takes the initiative to the project in a letter, as appears from Kernell’s reply in which he certainly supports the plan, but in a tone that is polite rather than enthusiastic. This fact illustrates an important feature in Malla Silfverstolpe’s relationship to writing: she seems to have felt a strong need to write for someone, to establish a relation with a specific reader.

Malla Silfverstolpe’s need for a special reader reveals itself not only in relation to her confidential friend, Kernell, but applies to the entire salon circle. Time after time she expresses her desire to read her memoirs to the group and in that way make herself known to them:

“On the fourteenth, Malla was able to continue reading to her dear friends – it was indescribably enjoyable! The only thing missing in their relationship, in her friendship with them, was that, being new acquaintances to her, they actually did not know anything about her past, her childhood and youth. Through these readings they now also became friends of her youth, learning about all that had concerned her and made her develop.”

Here, the writing of the memoirs (like the salon) is described as a part of Malla Silfverstolpe’s search for friendship and appreciation, and, furthermore, a means to create continuity and coherence in her life.

However, the idea of a special addressee is also something that is part and parcel of the genre of the memoir. Writing one’s memoirs is an activity that is closely related to the dialogical culture of conversation and letter writing as it was developed in the salons. Furthermore, reading her memoirs aloud to the circle, as Malla also did, becomes a way of testing their value: like others writing for the general public, she measures herself against the semi-public readership of her own group.

That Malla Silfverstolpe had the ambition of reaching a public readership with her writings is indicated not least by her perseverance in her work. For roughly twenty years of her adult life she is nearly always working on her ‘memories’. In 1840 she also published the short novel Månne det går an? (Can It Really Be Done?) as a contribution to the literary controversy surrounding Carl Jonas Love Almqvist’s novel Det går an (1838; It Can Be Done!; Eng. tr. Sara Videbeck). Malla Silfverstolpe’s contribution was received with acclaim and led, among other things, to her contact with Fredrika Bremer, who became a new ‘chosen reader’ to her. It was Fredrika Bremer’s encouragement and advice that inspired her to rework the memoirs during the 1840s. When, in 1853, Malla Silfverstolpe completed the fair copy of the manuscript, she was about to turn seventy-one. Her relatively advanced age may have contributed to the fact that the memoirs were not published. Furthermore, they included material that was sensitive for those around her. For instance, the poet C. W. Böttiger, her last love interest, who, together with Lindblad, was entrusted with the responsibility for the manuscript after her death, spoke firmly against publication.

As an example of the autobiographical genre, Malla Silfverstolpe’s Memoarer combines a chronicle-like narrative, which is concerned with external people and events, with a more intimate, personal account that focuses on the development of the subjective ‘I’. Where the text is most successful, the inward-looking and the outward-looking parts of the narration blend seamlessly together. This is especially the case in those passages in the two first parts of the memoirs that deal with her childhood and youth. Here, the artfully crafted text has the character of a novel. By being described in the third person throughout the memoirs, the ‘subject’, ‘Malla’, generally comes across as a kind of romance heroine, but in the beginning the novelistic impression is intensified by Malla going through the phases that are typical of women’s novels of development.

The Malla Figure, the Narrator, and Love

As a kind of foundling, the motherless Malla lands, six months old, in Sweden, wrapped up in her father’s cloak. Departing from Finland, her boat had been close to sinking in a storm, and the passengers had been forced to spend two days huddled on a cliff. At this point the protagonist of the memoirs is introduced. She is described as “ugly”, with “a dark complexion” and “a sullen appearance”. “Under normal circumstances this child would not have caught anybody’s attention.” As a child, Malla bears resemblance to the many Romantic outsider figures in the period’s literature: she is “a strange girl”, remarkably intense, capricious, and stubborn, and “unusually ambitious”.

Against this background of being different and “exceptional”, a personality structure is developed in the Malla figure: a yearning for community, closeness, and love – a “longing for bliss” combined with a constant struggle with the feeling of not being “meant for bliss”. What is going to be her main characteristic is her single-minded focus on the emotional sphere, the emotional intensity that she is capable of creating. It is this “burning heart” that makes Malla stand out from her surroundings and also makes her swing between happiness and misery, between the feeling of belonging and that of being an outcast. As a woman, she seems to be both angelic and demonic. One moment she presents herself as a heroine of the intimate sphere, to whom love is a “calling” and a “religion”; the next moment she comes across as a tragic and headstrong Byronic outsider, an “exception within society, nobody’s daughter, nobody’s sister, nobody’s spouse, nobody’s friend”.

However, the Romantic view of the human being and the narrator’s Romantic attitude, which characterise this description of the Malla figure, do not go unchallenged in the Memoarer. The voice of the Romantic narrator is always in dialogue with a sober, conventional narrator who sceptically distances herself from ‘the exceptional human being’. Especially in the first parts of the memoirs, the reader is often reminded of this voice, which seems to be influenced both by eighteenth-century rational thinking and by Malla Silfverstolpe’s reading of literature of a Realist stamp, in particular Fredrika Bremer. The tension between the different perspectives on the Malla figure is especially evident in the description of her youth and its big crisis, that is, her choice of a husband.

The problem that dominates Malla’s youth is how her “longing for bliss” can be fulfilled in a socially acceptable form. She is described as being in love with love itself and in love’s possibilities of offering her a richer life. However, as the pressure on her increases with regard to “considering her future destiny” – that is, marriage –, love becomes a threat and a burden. “She did not want to attach herself to anybody. Her instinct told her that this could be dangerous to her”, she writes at one point.

By being associated with marriage and the whole of her future life, love becomes something so serious and threatening that her ability to experience and accept love seems to be undermined. The spontaneity of her feelings disappears when she anxiously asks herself, every time she falls in love, if her feelings are genuine and if the man is the right one. Her contacts with the opposite sex are also complicated by the fact that she is primarily looking for a romantic relation and that she fears and distrusts sexuality. The young men in Malla Silfverstolpe’s circle are, on the one hand, described as mentors, “brothers”, and, on the other, as beaux, in a way that confuses the Malla figure – the devoted comradeship is constantly disturbed by the “many and passionate brotherly caresses”.

Eventually, love becomes so complicated for the Malla of the memoirs that it can only exist as an ideal; her love becomes love at a distance, and her only true lover is the one who is to be found in her dreams. This is a general pattern in the Memoarer. It influences her life with the Edsberg circle of her youth as well as with the Uppsala circle, and it also determines her married life. When she finally forces herself to choose Silfverstolpe as her husband, she does this with the important reservation that she is not willing to let go of her contact with her other suitor, the politician and poet A. F. Sköldebrand. She says that she wants to “combine her love of DG with her friendship with AF”. This turns out to involve her developing a kind of sensual everyday love of Silfverstolpe, whereas all through her marriage she maintains her idealised romantic interest in Sköldebrand through letters as well as hasty, furtive meetings.

The picture that is drawn here of the complex of problems surrounding the issue of love can easily be read out of the memoirs, but it goes beyond the explanation offered by Malla Silfverstolpe herself in her role as narrator. Neither in her Romantic nor in her ‘sensible’ persona does she ever question the idea that marriage is a woman’s mission in life. The Malla figure’s difficulties with regard to choosing her spouse are not presented as a social problem but as an individual problem that leads to a wrong decision. It is the Romantic voice that dominates the description of Malla’s final choice between Silfverstolpe and Sköldebrand. She is described as a tragic “victim” (dramatically italicised), a suffering, irresolute heroine who seeks consolation in viewing her triangle drama as mirroring Julie’s drama in Julie ou La nouvelle Hélöise. The course of events ends with the wedding, which is described as a kind of martyrdom. At her wedding, Malla’s face is “ashen grey” and her gaze is “lifeless”; in her married life she is said to carry a “locked up and choked sorrow”, which manifests itself in her prematurely broken health.

However, as soon as the narrator of “the burning heart” has spoken, the ‘sensible’ voice speaks in turn. To this voice, the Romantic searcher is above all pathetic, a “romanticised, sentimental fool”, who had already in her youth been ruined by “flattery” and who has forfeited her possibilities of becoming a “capable housewife”. Despite all her dramatic assertions about being forever wrecked, owing to her marriage, she is depicted as incorrigibly high-strung and dreamy, be it with regard to new romances or “unforgettable” conversations or promenades. The impetus of emotion drives the action on and constantly creates new, “unforgettable”, happy or unhappy moments, whereas reason with its reflection and self-criticism is a help in everyday life.

The continuous dialogue in the memoirs between passion and reason, Romanticism and Classicism/Realism, is related to the contemporary discussion of literature and feminist politics. In the portrayal of Malla as a Romantic and exceptional human being, the subjective ‘I’ and the personal individuality are emphasised in a way that appears, for the period, gender-politically radical and that clashes with the view of marriage found in the memoirs.

However, the Romantic attitude is not only radical, it also has a ‘pious’ side, which ideologically concurs with the Romantic middle-class ideal of the woman and the idealising of her role in the family. It is obvious, for instance, that the salon fulfils the function of a ‘career’ for Malla Silfverstolpe, but in accordance with the Romantic middle-class ideal of the woman and of love, this has to be disguised by way of presenting the salon life as family life. The love affairs, for instance, are often looked upon as mother-son relationships, and the members of the circle primarily become meaningful as substitutes for the increasingly absent relatives.

“What am I to do with this […] oh, so strong emotion?”, Malla Silfverstolpe asks in one of the diary excerpts in the memoirs. This is a question that lies behind the whole of the account and that remains unanswered: neither the Romantic idea of love as the road to self-realisation nor the sensibly realistic ideal of the housewife offers a satisfactory answer. Yet, with her close examination of the conditions of emotion, Malla Silfverstolpe offers a unique insight into the contradictions of women’s lives and women’s culture in the early nineteenth century.

Translated by Pernille Harsting