The oldest and most widely used form of women’s literature in Finland was, as in the other Nordic countries, the oral tradition of folklore. Thanks to Romantic and nationalist movements in the early part of the nineteenth century, a cultured audience became aware of this folk poetry. A literary tradition written in the Finnish language was still in short supply during the nineteenth century; the oral tradition thus had to provide material for the history, the ethnic religion, and above all the literary art of a small population. Proof that world literature could also be produced in Finnish came in the form of Elias Lönnrot’s (1802-1884) national epic Kalevala (1835, 1849) which, like the lyrical poems in Kanteletar (1840), was based on a compilation of folk poetry.

The value of oral literature from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries is so much the greater because the folk collectors did not amend the texts, but recorded them in the form in which they were originally presented. Only the two epic poems Kalevala and Kanteletar, which were intended for larger audiences and were edited and amended by Elias Lönnrot, can be said to be self-contained literary works.

The work of collecting the material received financial support from the government and was organised in as efficient a way as possible. The result was one of the world’s largest collections, not only of oral poetry, but also of women’s poetry. At least half of the recorded texts come from women: female singers and narrators.

Archival material of women’s oral poetry has been published in the form of scholarly anthologies, the major works being Suomen Kansan Vanhat Runot (thirty-three volumes, 1909-48; The Ancient Poems of the Finnish People), and Finnish Folk Poetry 1: Epic (1977). The latter makes the material available to an international readership.

The following section will only look at part of the extensive tradition: the ancient runes, documented in Kalevala meter (lyrical poems and ballads), and itkuvirsi (lamentations), which were sung exclusively by women. In all, there are approximately 145,000 texts in the first group, and approximately 3000 in the second. The major part of this material is kept in the Folklore Archives of the Finnish Literature Society in Helsinki.

Nineteenth-century collection of material from the oral tradition focused on the content; rarely was any attention paid to the bearers of the tradition – the people who sang the songs or told the tales. We know that many were women, but virtually all of them remained anonymous and faceless.

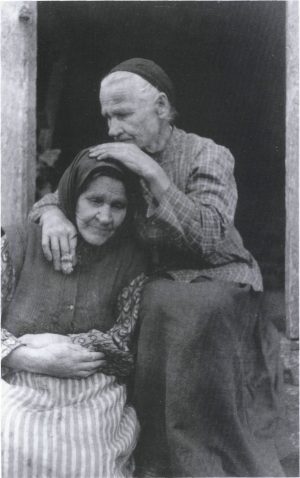

However, we do know the identities and contributions of some women informants. Mateli Kuivalatar (Magdaleena Ikonen, 1777-1846) from the north Karelia region, and Larin Paraske (Paraskeva Nikitina, 1834-1904) from Karjalankannas (the Karelian Isthmus). Elias Lönnrot tracked down Mateli Kuivalatar, and the old woman’s lyrical songs inspired his work when fine-tuning the collection Kanteletar. Larin Paraske was the only nineteenth-century female singer to have her entire repertoire written down – by a local clergyman, Adolf Neovius, from whom she even received modest payment for her narrations.

Mateli Kuivalatar and Larin Paraske were peasant women living in poverty. Their lives were dominated by ceaseless toil, a relentless battle to ensure the survival of the family. Kuivalatar bore eleven children in all, five died prematurely; of Paraske’s nine children, six did not reach adulthood. Paraske suffered such hardship that at times she had to resort to begging.

Russian-Karelian Anni Lehtonen was a peasant farm worker. She was widowed at a relatively early age, and had to provide for six children on her own. Lehtonen kept herself and her family alive by working as a day-labourer and by begging. In wintertime, she crossed over to the Finnish side of the border and worked as a washerwoman and bricklayer’s assistant.

Mateli Kuivalatar was a Lutheran and had learned modest reading skills at confirmation classes. Both Larin Paraske and Anni Lehtonen were illiterate, and they followed the Orthodox faith.

Mateli Kuivalatar’s and Larin Paraske’s songs show the diversity in the oral folk tradition. Three genres are predominant: ballads, lyrical songs, and lamentations. In the case of the ballads and the lyrical songs, the verse meter, which made memorising easier, was the same: trochaic tetrameter with alliteration (what is known as Kalevala meter: álaháll on állin míeli), with various stylistic parallelisms. The lamentations, on the other hand, did not follow one single standard verse meter, but were to a greater extent based on improvisation during delivery. The most well-documented singer of lamentations was Anni Lehtonen (1868-c. 1940). She was originally from Russian Karelia, but had emigrated to Finland.

The folklore collectors were men, and the disparities between them and the women singers were immense. Difference of gender was but one factor. Difference of social class was another. Students or scholars from middle-class backgrounds wrote down the songs; the female agents of the oral tradition represented the peasantry and many of them were, in terms of both language and religion, ‘different’ – that is to say, Karelian-speaking Orthodox. Taking this complex background into consideration, the quantity and quality of the texts is astonishing. Despite all the divisive factors, transcribers and singers managed to communicate with one another. This circumstance has given rise to the idea that a male representative of an unfamiliar culture would find it easier to make contact with the women of the people than with its men. It has been argued that the men might view the collectors as a potential threat from a higher social class and as rival ‘males of the species’.

Many of the collectors preferred and appreciated the same genres of folklore as the women. Although the genre hierarchy placed the epic songs sung by men (the songs that provided the basis for Kalevala) highest, the women’s favourite songs, the lyrical songs, were also written down. Lönnrot’s Kanteletar has argued persuasively for the recognition of their importance. The male collectors of the oral tradition found the lamentations most alien – representatives of a different culture had difficulty in comprehending the archaic universe of the lamentations, which was, moreover, rooted in a purely female empiricism.

The Sung Tradition

In the nineteenth century, the old female song tradition was most strongly represented in the east, in Karelia, with its complex cultural background: for several centuries part of the region has been variously under Swedish and Finnish administration, another part under Imperial Russia and then the Soviet Union. South Karelia, adjoining the Gulf of Finland, differs in many respects from the northern areas of wilderness, distant Karelia bordering the White Sea. The picture is made no less complex by three languages being spoken: Finnish, Karelian, and Russian. The population is also divided in terms of religion: between the Russian Orthodox Church and a Protestantism that has retained features of the old ethnic religion.

The songs clearly reflect the harsh conditions in a culture coloured by the poverty of the peasantry. The main occupations – grain growing and cattle breeding – involved a considerable workload, also on the part of women. Alongside this toil, they had to cope with childbirth and caring for infant children. The women’s lot in life, as well as their poetry, was strongly influenced by the most common burdens of pre-industrial culture: poverty, disease, and war. The load became even heavier as a consequence of an eastern European feudalism that had spread to parts of Karelia. The tough grind of life as day-labourers or in outright serfdom tied the peasant family to the estate, impeding any kind of personal initiative and enterprise.

The peasant woman spent her life in the setting of family, farm, and village community. The highly patriarchal aspect of family life was, for example, evident in the circumstance that the woman, according to popular custom, could not inherit land. Close family relationships also had patriarchal elements. Marrying off a daughter could well seem to have been a transaction between men: the engagement gift comprised the sum of money that the young woman’s father received in payment from her fiancé. The only legitimate position of power for a woman was that of mother-in-law; a woman’s relationship with her son was thus often, presumably for this very reason, more important to her than her relationship with her husband. The son also played a role as protector; in the event of her husband’s death, a woman’s son assumed the responsibility for her support.

From first to last, the women’s lyrical songs reflect their perception and emotional awareness of their lives – as children and young girls, and later as wives and widows. The songs also deal with relationships with neighbours and with the other women in the village, a vital group that was larger than the family and which offered support during periods of hardship, but which also monitored and criticised the woman.

Mercy and Charity: Women’s Elegies

Small farming communities are often perceived as harmonious, even idyllic societies. The picture we get from the Karelian women singers, however, looks completely different. They depict the woman’s life as cheerless and weighed down by endless toil, leading to a state of depression that might run so deep as to become a longing for death.

The woman singer addresses, for example, her mother, expressing her wish that she had been done away with at birth:

Better had it been, dear mother,

Magnificent being who once bore me,

My sweetest nursemaid,

Beloved source of milk,

If you had thrown my cradle into the fire,

Thrust it into the hearth,

Laid it among the flames,

Than to rock me in it

Until I was consumed by grief

And had grown dark with care.

The women’s songs often depict conflict-ridden and difficult human relationships. Fantasies full of hatred play a big role – the female singer wishes, for example, death upon her adversaries, or she expresses the hope that this adversary will bear an ‘unfinished’ baby, “a foetus like the foetus of a pig”.

The peasant women were aware that their workload was necessary to the survival of their families. The knowledge that they fulfilled the demands made of a woman in terms of work, the requirement to be ‘a good worker’, was a major contribution to their self-assurance – a self-assurance that also finds expression in the songs:

What does my husband have to complain about?

I am a woman like all others:

I milk the cows, bake the bread,

Watch the children, boil the cabbage,

Reap five and twenty sheaves,

Even lie beside him in bed.

Mitä Miusta mies toruvi?

Niin olen nainen kuin muutkin naiset:

lehmät lypsän, leivät paistan,

lapsen katsot, kaalin keitän,

niitän viisi viisikkoa,

vielä viesessä makajan

.

The understanding of a woman’s role as expressed in the songs was no different to the patriarchal society’s general view of gender roles. The songs certainly often complain about the burdens of being a woman, but no alternatives are offered. Songs dealing with the lesser worth of a daughter vis-à-vis a son settle for warning parents and extended family against acting with extreme brutality by killing the daughter. The two valuations are not questioned. Any kind of rebellious content pointing to change is not exactly writ large, even in songs that criticise – indeed, deride – men. It is not the man’s dominating position in relation to the woman that is criticised, but the fact that a man does not always fulfil the demands made of him by the culture. Compared with other men he is not a ‘man’. Only a small number of ‘mutinous’ ballads make it clear that the woman does not accept having her role in society defined by men.

The women’s songs also express experiences of anxiety, loneliness, and emptiness. The imagery invokes ice, wind, and endless cold. The women project their feelings right out into space:

My farmyard is as long

As the wisp of a cloud,

My path to the well is as narrow

As the stripe of a rainbow,

My doors open towards the heavens

Where the Big Dipper

Twinkles.

Niin on pitkät miun pihani

kuin on pitkät pilven rannat,

niin on kaiat kaivotieni

kuin on kaiat kaaren rannat,

sinne oikein oveni

kunne oikein otavat.

This song by Mateli Kuivalatar can be understood as an encounter with cosmic destiny, but also, in a more concrete sense, as an elegy of the homeless. Others live on their own farms, but the person singing has a farm bordered by clouds, her track to the well is compared to the edge of the rainbow, and the spot where she should have her door is marked by the Ursa Major constellation.

In studying old folklore texts from the perspective of the people who sang them, allowances have to be made for variation in meaning. A song could take on new significance as it moved from setting to setting, and from one female singer to the next. Most of the singers, however, would seem to have imbued the texts with the same meaning time after time.

There are many elegies in which the concrete explanation for the woman’s suffering is her onerous lot in life. The motif of countless elegies is that of being unprotected, ‘homeless’. It was a vital necessity for the woman to belong to a group comprising father, brother, husband, or son. A woman without a family headed by a man, without an ‘owner’, was of little worth seen from a social perspective, and it was also difficult for a single mother to provide for herself and her children. She had to work as a servant. If she was too weak to work, she had to beg. A number of versions of the poem beginning Sad is the seagull, which is one of the most admired Finnish elegies, portray the feelings of the wandering beggar-woman:

Sad is the seagull

when swimming in wintry waters

sadder still the homeless

wandering in the wide world

unhappy the heart of the dove

when picking a foreign pittance

throbbing the throat of the sparrow

when drinking icy droplets

colder am I and wretched

colder still than that.

In this poem, the woman uses traditional metaphors to link herself to nature. Sea birds and little birds are the female singer’s sisters and brothers in misfortune when, in her suffering, she turns her warm compassion to the birds and the freezing person.

By no means all the songs identify the cause of the woman’s suffering. Generally, she simply describes the heaviness of her heart: “I was bathed in tears”, “I have more worries than the pine has cones”. Some songs describe utopian, fabulous pipe dreams that have evolved as a channel by which to overcome distress. She tells, for example, that she will transfer her worries to the horse with its large and strong head; she might also wish them away to the bottom of the forest lake, or she will tie them up in her hairband.

Besides her sorrows and worries, the woman’s hatred and bitterness are also conspicuous themes in the folk poetry. The songs express the woman’s undisguised negative feelings about her husband and the family that has appropriated her as daughter-in-law. In Karelia this extended family could well include a number of married couples. The poems depict the mother-in-law as the chief adversary of the young woman.

The songs also express the bitterness felt by servant towards mistress. Another hated group, besides the family, was that of the old village women who kept surveillance and made personal remarks. This group had a significant influence on young women’s lives, and it was they who assessed a girl’s suitability and viability on the marriage market. Tension between the female singer and the village community could sometimes be depicted in strident tones, but conflict might also be played down and rendered in a calm and principled voice, as in one of Mateli Kuivalatar’s songs:

When somebody censures

Or finds too much fault with me,

I straighten my back,

Hold my head higher,

I strut like a stallion

Or kick back like a foal.

But when somebody sings my praise,

I lower my head.

The Mother

Finnish folk poetry is generally highly restrained in its manifestation of positive feelings such as love, tenderness, and affection. Seen in this light, songs by the women of South Karelia, with their conspicuous mother theme, make an almost passionate impression. Scholars have been surprised by the intensity of longing for the mother expressed by adult daughters. Ingrian songs, for example, have a motif in which the female singer wishes to fly like a bird to the mother’s grave in order to dig down in the sand with her bare hands and bring the mother home so that she can caress her daughter’s head.

In accordance with the oral tradition, the folk poetry only rarely presents confidential, profound thoughts or complex symbolism. The imagery is simple, with the same metaphors frequently used in a number of different songs. Comparison between the songs can thus be illuminating: several versions of a song or a theme might well explain something that seemed inscrutable in the first version. The mother might, for example, be presented as a warm summer in the Karelian woman’s cold life, and comparison with other mother songs will provide an explanation of this metaphor. Her mother is a point of reference as regards the woman’s new family – the husband, mother-in-law, or stepmother – a contrast highlighting their harshness:

Warm, but not like summer,

Is a strange woman, not a mother.

Snapping out her advice,

Glowering under her armpit,

Admonishing me over her shoulder,

She drags me out of bed in the morning:

“Up and at ’em, you lazy whore,

Wake up, you rotten piece of wood,

Go get the fuel, old moss-head,

Light the stove, miserable maid.

The sun has already risen over the forest

The morning has climbed high above the trees.”

When my mother roused me

In the morning, she would say:

“Wake up, dear child,

Light the stove, fruit of my womb,

The day is about to break.”

I looked out the little window:

The sun had long risen over the forest,

The morning had climbed high above the trees.”

Most of the poems on the theme of the mother express longing; they are songs about love lost. The mother might be dead, and perhaps she has been replaced by a stepmother. Or perhaps the daughter has lost her mother by marrying at a very young age and moving, to another family, maybe to another village.

In the adult woman’s life, the mother was a dream expressing both security and gentleness; in the terminology of the songs: “mercy”. There was no guarantee that anything similar would be the case with a husband. His job was to look after his wife, while also attending to his mother – the real mistress of the farm.

In a life of hardship, the dream of the mother appeared in an even stronger light. Dreams and songs provided the opportunity to escape back into an idealised childhood, in which the longed-for kindness and tenderness could be retrieved:

Not all mothers care,

Not all women suckle

As my mother suckled me.

As the female parent, she tended to me,

Tirelessly watched after me:

Three times of a summer night

She would run down to the stream

To gather water

And carry it back in her bowl

To wash her little daughter,

To bathe her precious water lily,

Until these wretched days,

These dismal times.

Children

A central motif in the extensive corpus of women’s songs is devotion between mother and daughter. However, it seems to be a curiously one-sided devotion. The daughters do the loving, whereas the mothers place no particular store by their daughters.

The reason for this can be sought in the structure of the peasant family, and the values pertaining thereto. Women also adhered to the view that ‘it was a girl, a nobody was born’. Many songs on the theme of children describe the family’s offspring in similar terms:

I rock my little baby boy,

I rock him to console myself

In my old age.

I rock my little baby girl,

I rock her for a strange house

As a wife for a boy,

As a hen for a shopkeeper.

“My baby” or “my treasure (“juuri”) is often a boy. Lullabies dream of a time when the son has grown up and furnishes his mother with bread and brings a daughter-in-law back to the farm to ease her burden.

Although considered less important than a son, a daughter was easier for the mother to identify with because they shared a common fate. While lamenting the future of the baby girl, a lullaby was also a way for the mother to mourn her own life and think about days gone by.

A woman who gives birth can never imagine

What she is rocking her daughter for:

A man with his own cottage

Or a man without a dwelling

A man with plenty of bread

Or a man of no means.

Most Finnish lullabies teem with bright images of birds, flowers, berries and well-known domestic animals. But they also contain themes that are difficult for contemporary readers to understand, such as rocking a child into Tuonela (the underworld). What were women thinking when the lulled their children to sleep and sung lullabies? Perhaps this one, which was widespread in both Finland and Karelia:

Lull the child into death

Into the church’s chamber

To sleep under the grass

Where the fine sand lies,

Where the cottage stands with its turf roof.

Tuutipa lasta tuonelaan,

tuonne kirkon kammioon

alle nurmen nukkumaan,

joss on hieno hiekkapelto

tuvan katto turpehista.

A mother wasn’t the only one who might sing lullabies to her children. Agrarian society did not regard childminding as important woman’s work. Even a mother could earnestly rock her child into the kingdom of death. The child might have been anxious or fatally ill. It might have been more than the mother, or even household finances, could handle. Or perhaps she was comforting herself with fantasies of death.

Historical research tends to assume that women in a culture with a high birthrate and infant mortality had a fatalistic or matter-of-fact attitude to the death of a young child. In the early nineteenth century, almost one-third (close to one-half in some areas) of all Finnish children died before the age of two. The lullabies testify to a view of death much different from that of the contemporary world. Death did not represent an ultimate severing of ties among members of the family. The dead were still regarded as part of the clan. Hours of remembrance, dirges, dreams and contemplation maintained contact with the deceased.

A woman who had lost a child could also find consolation in the Christian concept of sin. The child had been saved and had gone to heaven because it was still pure. Such a perspective left foom for tenderness and beauty when describing the child’s death.

Go to sleep, my little grassbird,

Grow weary, wagtail mine,

Sleep in the soothing grass,

Lie in the restful soil

With glorious sand over your eyes,

Rich earth over your mouth,

Young grass as your quilt.

Men

Some historians argue that direct, outspoken love songs would have violated the norms of traditional agrarian society before the upheavals of the late nineteenth century. Because stability was the most cherished value, passionate and sensual love was considered neither admirable nor desirable. Religion also sought to rein in such feelings. Given that people lived in extended families, a young couple was expected to exhibit restraint in the company of others.

Nevertheless, the most famous Finnish songs of all is a glowing avowal of love. “Jos mun tuttuni tulisi” (If My Friend Came Wandering) was first written down in the eighteenth century. It was translated and printed in English, German, French and Dutch in the early nineteenth century. Among the translators were Goethe after A.F. Skjöldebrand. The first known interpreter was a young peasant woman who served at a vicarage in south-west Finland. The recorded material, however, suggests that even men sang it. Given the neutral first-person pronoun in Finnish, the narrator remains undefined.

If my friend came wandering,

If he choose to appear one more time,

I would shake his hand firmly,

Even if he were holding a snake,

I would offer my lips right away,

Even if his were covered with wolf’s blood,

I would throw my arms around his neck,

Even if he had brought death with him,

I would lie at his side,

Even if he were on a bloody sheet.

Other love songs with female narrators are restrained and conventional by comparison. The wistful songs of widows may present the relationship between the sexes in a more affectionate light. The dead spouse appears primarily in his capacity as protector and benefactor, the one who furnishes his wife and children with bread. The theme recurs in laments. Men’s labour is a common motif. The sounds they make while working on the farm, once so comforting and reassuring to their wives in the house, have fallen silent. The songs also describe the husband as a sexual partner and object of devotion: he is “my darling,” “the one under my covers.”

Nevertheless, women’s disillusionment with their husbands gave rise to many lyrical songs that described men’s faults without beating around the bush, sometimes cruelly. Whether the laments were sung for men and their relatives or only when other women were around is not known.

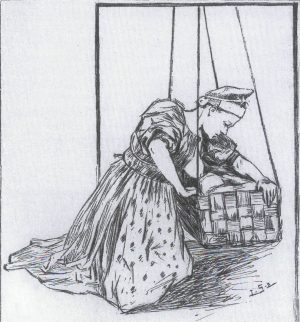

The songs mocked weakness: a feeble or disabled man provided poor protection in a culture that prized physical performance above all else. Such is the obvious theme of the highly popular and ironic “Minä jauhan Jaakolleni” (Here I Stand and Grind for Jaakko). A woman uses a hand-mill to grind corn for her husband, “the bandy-legged”, “the club-footed”. Nonetheless, he offers certain undeniable advantages: he can still fish and he can’t be whisked away as a soldier. But his worst shortcoming, referred to in veiled terms, is his inability to beget a son.

I grind away, poor old woman,

With mouldy ears I stand and turn –

My sister-in-law won’t grind,

Nor my daughter-in-law.

Long before the age of literary realism, popular poetry described women’s ordeal with brutal, alcoholic husbands. The depictions are often naturalistic; a recurring theme is a drunkard who vomits all over the bed. But women’s painful, humiliating experiences can also be expressed with greater delicacy:

Often over me, unhappy one,

Over me, unfortunate one,

I feel words rain down,

Stream from above,

Like burning sparks,

Or iron hailstones.

Often on me, unhappy one,

Over me, unfortunate one,

I feel a breath of fresh air on my cheeks,

A fist in my face,

For nothing I have done,

Undeserved on my part.

Songs

Oral poetry by women was both collective and individual. Tradition as passed down from one generation to the next determined the themes, images, and metric technique. How the songs were used was not up to the individual; unyielding conventions dictated which ones were suited to particular occasions, who could perform them, and whom they could be performed for.

Only recently have researchers begun to explore the uses to which songs by women were put, as well as the cultural significance they carried, in popular Finnish poetry What is clear, however, is that the oral tradition served the same purpose as art in general. It permitted people to deal with and articulate experiences and feelings about subjects that were awkward or taboo in day-to-day life. Anthropologists who research the oral tradition have noted that female singers could exert pressure on their surroundings. A lament or an aggressive song was a way of communicating with family and friends. A woman could describe the unfortunate situation in which she found herself and verbalise her hope that it would change for the better. Singing games and arousing sings also hinted at the need for interpersonal relationships, particularly in the case of young people who were looking for mates.

The local community and its women were fond of both songs and those who sang them. Women conveyed a feeling of joy when their songs could be used for dance and play. They served as callers and helped lead the dancing. A skilled singer was fully aware of her importance. She boasts in many of the songs. For instance, she might brag about how many songs she can sing and assert that she knows more words than can fit in the cottage. Or she might assure her listeners that she can sing for nine nights on end. Sometimes she even claims that she is a superior lyricist, that she taught herself how to compose songs whereas others needed to learn from somebody else.

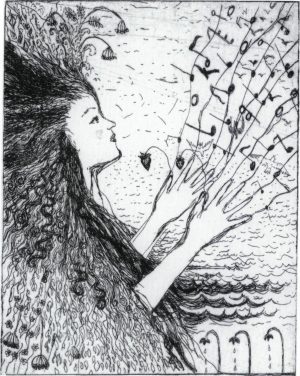

Lastly, she may pride herself on the impact of her songs. As the daughter of seers, she possesses magical powers:

I shall sing the water lily of the lake

The sea’s reeds to fish

The sea’s grains of sand to peas

The sea’s waves to the perch.

Popular ballads provided female artists with the first opportunity to assume their place on the stage of Finnish literature.

Aesthetic analysis of women’s oral poetry is still in its infancy. Estonian and Finnish scholars have had the opportunity to interview women singers living in eastern Estonia (the Seto people). This poetry has its own aesthetic vocabulary. Singers strive to maintain a holistic form in the poems. The expression “a beautiful song” is used for lyrics that are both semantically rich and sonorous. Furthermore, singers must master the art of versifying. A proficient singer must be able to come up with “new words” for the lines of the poem and their individual parts. That is, they must master both parallellism and alliteration.

The delivery varied depending on circumstances. According to Paraske, lullabyes and playsongs must always be sung in the same manner, while wedding songs and songs for dancing could be improvised on the spot by throwing together various poems.

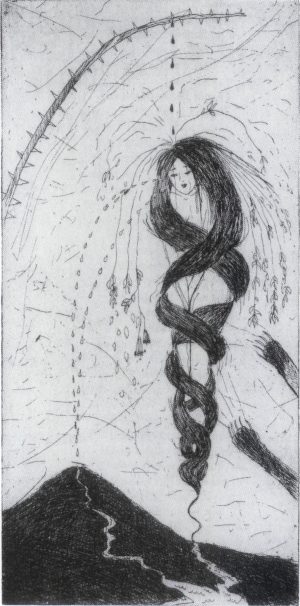

Women and Death Karelian Laments

Laments survived in Karelia until the twentieth century. Performed only by women, they represent a very old genre that contains elements of prehistoric culture. Dirges, the most important kinds of laments, were sung when people died. The songs helped women manage relations between the community and the world of the dead.

The earliest agrarian communities were clan-oriented. Whether they tended to be patrilineal as in nineteenth century Karelia is not known.

Family ties remained intact after death. The dead were also seen as influencing the lives of their descendants in a number of ways. In other words, family-centredness and the cult of death were intimately connected.

The tradition of laments was strong in eastern Finland, in the orthodox areas of Karelia. Souls made thier way to the kingdom of death with the help of a woman. Unless a woman sang a lament, they could not join other family members who had died but had to wander near their earthly homes as restless and dangerous creatures.

The female mourner is not exclusively a Karelian phenomenon. The participation of women in death rituals cuts across many cultures. The Christian church fought these traditions throughout Europe and issued prohibitions against songs of mourning. The reason was that the cult of death, the foundation of the old ethnic religion, manifested in popular rituals. Power was also at stake. The goal was that the most important rituals be under the aegis of an official institution like the church and its authorised representatives instead of clans or the local community. Furthermore, men rather than women were to be in charge.

Why do so many cultures rely on the weeping of women and not men for guiding the dead to the other world? Some researchers argue that public mourning and the visible expression of emotion it entails is often permitted for members of society who are regarded as less important. According to a psychological and socio-economic explanation, women are more dependent on close relatives and more intimately tied to interpersonal relationships.

The association between women and the cycles of nature are another reason for their more prominent role in the rituals that celebrate and commemorate those cycles. Thus, the Karelian laments relate women’s capacity for reproduction to ritual mourning, and the words reflect their awareness of their role as links in the “great chain of being.” Remarkably often, human relations are described in terms of mother and child. Even the singer’s father becomes a child “whom my grandmother suckled”. A sister has come out of the same womb; she has “lain in the same blood”. A husband is also regarded as a child: “born of my mother-in-law” or just “born of woman”.

The laments unite life and death. The women often gaze in opposite directions: towards the family’s children (the future) and the those who have departed (the past). Their weeping is painful and agonised. They pray to the Creator and the dead for help in bearing the burden of their lives and raising the next generation to assume the responsibilities of adulthood.

How shall I bring up my little cranberries

And take care of my young protégés?

With sombre thoughts I start to raise them,

I shall bathe them in my abundant tears

And immerse them in the rivers of my eyes.

The mourners sing mostly as daughters, sisters, wives, and mothers – the roles that are the source of their true kinship. Only her husband, the person with whom she has conceived her children, is not a blood relation.

Women rarely sang a lament for a neighbour, friend, member of her husband’s family, or someone else who did not belong to her own clan. However, all women in the village who sang songs of mourning would support both neighbours and their own families in times of sorrow.

The tradition was a concrete manifestation of a woman’s spiritual affinity with her own family even after marriage had separated them. Eventually she would follow her parents to “the holy whiteness” or “the magnificent Creator of the kingdom of death”. As a skilled mourner, she could establish contact with departed relatives by attending official commemorative rites, visiting graves or simply by being alone.

The lament represented a powerful message both for the dead and for living family members. It allowed a woman to appeal to her listeners and convey emotions so powerful that ordinary speech, not even ballads, sufficed. A lament could even be performed as part of a family feud or conflict between women in the village. If a grandmother wept openly on her doorstep, the neighbours understood that she had been mistreated by her family.

The language of love and fear

Songs of mourning have been referred to as the poetry of eternal farewell. They are associated with weddings and funerals, the most important rites de passage. A bride sings a lament when she takes leave of her family and friends, and her mother expresses her sorrow in the same way. Women gave free rein to their joy or grief in other situations as well. The dirge is regarded as older than other types of laments, which were patterned after it.

Most women could sing laments, and professional mourners were unknown in Karelia. Like other genres, however, laments had their specialists. Particularly skilled singers helped female relatives with wedding, death and burial rites.

Previous research regarded the songs as having relied more on improvisation than rote memory. More recent findings have fleshed out that view. Interviews with mourners suggest that they often rehearse with great care. They may keep a particularly good lament as part of their repertoire for decades and perform it in various situations.

These songs have been described as a magical, highly emotional, and consciously artistic means of communication. Women have used them to develop a language that has no counterpart in any other poetic genre, offering philologists a unique perspective. Nevertheless, the songs may appear rather incomprehensible to those who are unacquainted with the tradition. Compared to ordinary speech, many of the words have fairly vague meanings. Women who were deeply involved in the tradition, however, hardly considered the songs to be inaccessible. Quite the contrary, they saw the conventional circumlocutions and standard expressions, such as the way people are named, as a way of facilitating understanding. All of the singers in a particular area used the same terms for mother, sister, daughter, father, brother, son, and husband. The vague, changeable nature of the meanings were no problem for the listeners. The emotional timbre and vocal elegance of the expressions transmitted the message even in the face of “meaningless” throwaway words or lack of clarity due to the strength of the singer’s feelings. The songs were not bound by metre or prosodic structure. The phrasing followed the rhythm of breathing, alternating between longer and shorter tirades. Certain passages might be devoted to wailing and sobbing.

Researchers have not yet established whether the poetry of the laments was wholly female. There is no doubt, however, that women shaped the form and content of the genre, which stems from a tradition that they have preserved and carried on for centuries. It goes without saying that translations of the songs offers but a narrow peek into the power and magnitude of their poetry. Below is part of a lament that a singer performed when returning home to attend her sister’s funeral.

Why do I, a grieving woman,

See these footpaths as so sorrowful,

These fences as so downhearted?

Once upon a time these farmyards were beautiful

And sunny.

Why are these lovely chambers obscured now

By such dark and motionless clouds?

What strange and unknown sights meet

A grieving woman?

The last time I came to this farm

The song of the nightingale was everywhere,

The cheerful palaver of the house martins.

Why are the legs of the nightingales

Broken now,

The heads of the house martins crushed?

What strange and unknown sights meet

A grieving woman?

Why must she encounter

Such rivers of tears on the doorstep?

Wait! I will try to see whether a vessel has been prepared

To carry me across the sea of tears.

Look how a grieving woman comes home

To razor-sharp twigs that have appeared on the threshold.

Something strange and unknown now surrounds

These beautiful rooms.

The central objects of the laments are handled by means of circumlocutions. A dearly departed family member may not be referred to as dead or addressed as mother, father, sister, child, etc. The inhabitants of the other side are “white holy ones” or “dear saviours”. Direct appellations were regarded as too powerful and liable to entice the dead person to return. Like everything in the hereafter, even a beloved relative could be dangerous in one way or another. The deceased must be treated with skill and delicacy. Anything that could establish harmful ties with their survivors was scrupulously avoided.

The language of laments is also that of love. The impact of the expressions is softened through the use of diminutives and possessive forms. Alliteration and repetition are the most conspicuous stylistic devices. The metaphors are often taken from nature: swans, birds, butterflies, flowers and berries. Metonymic expressions describe the dead person’s function in life: the father protects, teaches and defines norms; the mother proides care and upbrining. Attractive, positive qualities are assigned to the deceased: the mother is “my darling who looks after me” and “the tireless nurse”.

The love that manifests in the laments has multiple implications. The most important is longing and devotion. Tenderness and conciliatory reverence can neutralise any danger. The implicit hope of the laments is that the dead will be satisfied with those who survive them and will take an amicable farewell. Summoned and guided by the rituals, they find their living relatives and appear as a bird, flower, butterfly or other appealing form.

The most dangerous opponent that the mourner had to wrestle with was her own pain. She watches over and wails for herself: “wretched woman,” “poor unfortunate bird.” The self-pity of the laments was also a social plea directed to family members, living and dead. Many listeners, particularly women, burst into tears and empathised with the singer’s emotions. Collective grieving helped the woman who had lost a love one to overcome her pain. The paralysing sorrow had to be subdued in order for her to go on living.

Seducer and Victim Popular Finnish Ballads

The definition of popular Finnish ballads as female poetry is based on their content, central themes and perspective. The ballads proceed from women’s point of view and concern their relationships with family members, fiancés or husbands. Apparently they were performed primarily by women and in female contexts.

The epic ballads in kalevalameter are among the oldest and were preserved by the peasant population without the benefit of written texts. Both legendary and other ballads follow the old Finnish runometer. Neither end rhyme nor the use of stanzas is part of that tradition.

Of an estimated 40 legendary or other ballads, approximately 100 different versions were written down.

Not much is known about the female and male singers of the oldest ballads, nor about how they were used or the cultural significance they bore. The simplest plots, which involve suitors or family members, were presumably for dancing or games. Songs with a ritual connection to agriculture emerged later on. However, the correlation was not fundamental to the genre.

Trying to date oral Finnish ballads is a difficult proposition. The genre of the ballad probably goes back to the Middle Ages, but not a single text from that period is of Finnish origin. The world of Finnish ballads is neither romantic, chivalrous nor mythological; it reflects the culture and day-to-day lives of the peasantry. A typical protagonist is a young woman – a maiden or new bride by the name of Katri, Kirsti, Anni or Marketta. Middle-class Annikainen and aristocratic Inkeri are the exceptions that prove the rule. The names of the heroines reveal the cultural sphere in which the plot unfolds. Their protectresses and role models were the Virgin Mary and all the martyrs who had managed to preserve their virginity.

Although a culture immersed in fertility rites did not regard pregnancy or loss of virginity as a disaster, Christianity turned sexuality into a problem. The relationship between the sexes took the form of war in which unmarried women had to defend themselves against the injuries that men threatened to inflict on them. Unsurprisingly, then, the most conspicuous theme of Finnish ballads is sexual conflict. The ultimate outcome is violence: a young woman falls in love with a perfidious stranger and exacts revenge with God’s help (“Annikainen”) or a band of maidens hang the unfaithful fiancé (“The Dragon and the Maiden”). Perhaps a young woman kills a stranger who has sneaked into her room (“The Man Slayer”) or hangs herself rather than submit to a man’s advances, after which he stabs himself (“Kirsti and Riiko’s Son”). A young man seduces his sister by mistake and has to go into exile (“Tuurikkainen”), or a maiden persuades her suitor to kill his wife and then refuses to marry him (“The Young Lady of Kaloniemi”). In a final ballad, a nobleman kills his wife and young son after having fallen for a rumour that she has betrayed him (“Elina’s Death”).

The most interesting ballads that date back to the Middle Ages can be seen as female protest songs. The ballads point to a period of cultural transition: their writers are well aware of the patriarchal norms to which Christianity subjects women, but they are not ready to accept them. Instead they carry on the tradition of the previous period in which women were portrayed as strong and relatively independent. The “fallen women” and the feelings of shame they were intended to elicit are conspicuous by their absence. Premarital sex is a matter that concerns both parties. The protest ballads appear to advocate that any social sanctions be directed at both women and men, as opposed to legendary poetry and prose that places all the blame on the woman.

“Annikainen,” the most famous medieval Finnish ballad, takes an ironic approach to the theme of seduction. A young middle-class woman from Åbo is vexed that she has squandered so much food, drink and money on her lover, a Hanseatic merchant who spent the winter in town but took off when spring arrived. God the Father and the Virgin Mary accede to her wishes and see to it that the man drowns in a storm.

The singer in “The Dragon and the Maiden” deals with the double standard in a more intellectual, ironic manner. The basic structure of legends, folk tales and ballads is turned upside down. The villains who are after the young woman are a youth and a king, while her saviour is a dragon. At the beginning of the ballad, a band of maidens are about to hang a young man because he “lay with a maidservant who had proud breasts” and got her pregnant.

Long is the linden we shall strip,

The linden is long and smooth;

Long is the raffia that we peel,

The raffia is long and wide;

Long is the rope that we twine,

The rope is long and supple,

To hang the fiancé

By the road, next to the gate,

Just when the king comes,

The castle’s oldest takes his stroll.

The king arrives and asks why the young man has been condemned to death. Incensed by the women’s administration of justice, he sentences the victim instead. But an unexpected defender appears:

The poor maiden was condemned

To be swallowed by the dragon;

But the dragon began to sigh and sigh,

To huff and puff: “I would rather swallow a youth,

With a sword at his side,

Rather a horse with saddle,

And a pastor with his congregation,

And a king with a helmet on his head

Than swallow a young maiden,

A young maiden, a young finacée.

A maiden can give birth to sons,

Spawn a shipful of blacksmiths,

For the great Swedish war,

To do battle with Mårten Danske.”

The last two lines refer to the naval war in the early sixteenth century on the southern coast of Finland between Sweden and Denmark. Its light, amusing tone notwithstanding, the ballad points the finger at women’s oppressors. The egoistic fiancé is a sexual predator, while the king who defends him is the personification of law and power. “The pastor with his pious gold,” another pillar of the patriarchal power structure, is mentioned as well. The final lines reflect a kind of gallows humour that mocks self-pity. The only thing that can acquit her is the dragon, an imaginary creature that has no real substance. Moreover, she must surrender her son to the kung and “the great Swedish war.”

“The Man Slayer” is narrower and more negative than the earlier ballads. The heroine has left the protest stage behind and turns patriarchal morality on the man himself. Certain features of the ballad are reminiscent of a court case. Based on the story of an attempted rape, it employs a legalistic dialogue to demonstrate what the victim should do to protect herself. Though vulgar, even brutal, the ballad follows the strict forms of patriarchal Christian morality. A woman’s “honour” required her to successfully resist everyone except her husband or fiancé. Popular poetry portrayed female honour as it had been codified in law: not so much a matter of preserving one’s virginity as refraining from damaging the reputation and status of the family and clan. Touching a woman was synonymous with injuring her owner – her father, brother, or husband – and bringing shame upon her family.

In “The Man Slayer,” a strange man makes his way into the fair Kaisa’s bedchamber; when she realises that he isn’t her fiancé, she stabs him in the chest. “A red stream flowed out on both sides of Kaisa’s bed.” The message of the ballad is encapsulated in the Kaisa’s reply to her brother’s recriminations. I have, she says,

Slain that man, saved my head,

Let go of my shame,

Thrown the insult from my eyes,

Cast aside my sister’s tears,

Cast aside my brother’s censure.

Ballads and the Rites of Spring

The ballads that date back to the Middle Ages were sung at the Helkajuhla, a spring festival associated with Whitsun in the southern Finnish village of Ritvala. The Catholic tradition survived into the nineteenth century. The fertility rite was performed at the beginning of the growing season. During the spring festivities, a procession of young women paraded along the roads between the fields singing ballads and legends about the lives of Mataleena, Inkeri and Annikainen. Each stanza is followed by a refrain along the lines of “they shouted in exaltation” or “how blessed it is to have God on one’s side, glorious Jesus as protection.”

Rites associated with spring planting were practised even before the Christian era. According to our knowledge from the sixteenth century, women were active participants in the fertility rites. The most important of these took place immediately following spring planting, when it was hoped that Ukko, god of the firmament and of thunder, would let it rain. This rain ritual had a sexual idiom.

According to an old poem, Ukko had a sexually eager partner, Rauni. Only when these two were united in the act of love would rain come to the land:

“And once the spring planting was done toasts were made in Ukko’s honour. The throng flocked around Ukko’s tun, and both maiden and woman grew inebriated and merry. Then much that was shameful passed, which was both heard and seen. And as soon as Rauni, Ukko’s woman, waxed lustful, Ukko began to spew and spurt in the high North. That gave us the blessed rain and another harvest.”

The phrase “much that was shameful” refers to sexual acts. Scholars are unsure whether we should take it to mean ritual intercourse, a ‘holy wedding’ (hieros gamos), or simply feasting and merry-making in beer-induced ecstasy.

In medieval times the old spring rites were modified and adapted to the ideology of the Catholic Church. The Whitsun feast in Ritvala remained a fertility rite, but all positive association with sexuality in word and action was expunged from the ritual.

According to some sources, the women singers were now required to be ‘pure’ maidens – women who had not yet had sexual intercourse.

The procession carried the same symbolic value as the ancient Finnish sowing festivals, with which the bishops were still finding fault in the sixteenth century. The goal was to boost crop yields and ensure a bountiful harvest. The most important participants in the festival were young women, i.e., future mothers. That may have been the reason the priests chose ballads about virginity, chastity, and fidelity for the women of Ritvala to sing. Of course, a black sheep managed to sneak its way in: Annikainen clearly drew pleasure from her premarital relationship and had no compunctions about having her lover drowned when he abandoned her. Still, the ballad issues a warning to young women: “May today’s maidens not submit to men’s supplications and follow the whims of the lark as I, poor woman, did.”

“Inkerin virsi” (Inkeri’s Song) is a Finnish kalevalameter version of the Danish-Swedish “Lagmansvisan”. The noble virgin who faithfully waits for her betrothed is an ideal fiancée, a univira,whose resolve cannot be swayed by time, news of death, or pressure by her family.

The theme of fidelity pleads the case of romantic love. By defending the sanctity of a committed relationship, lovers defy both family and friends. Inkeri’s family forces her to accept betrothal to another man, but “violence could not induce her to marry”.

The message of “Mataleenan virsi” (Mataleena’s Song) is more complex. The legendary ballad exemplifies the woman’s greatest sins and intrinsic evil. However, it suggests that even an evil and immoral woman can receive Christian salvation if she confesses her wretchedness and does repentance for her misdeeds. “Mataleenas kväde” declares the woman to be guilty in the spirit of the Church Fathers. The heroine is beautiful and fair, “a Christian Venus,” but an odious truth lurks beneath the surface. She is vain, consumed by her attractiveness, wearing gold and silver jewellery on any and all occasions:

The young maiden Mataleena

Went to the well to fetch some water

With a golden milk pail in her hand,

With a golden handle on her pail.

She gazed at her reflection on the bottom:

“Ah, poor girl,

How I have changed

How my fair hue has faded.

No longer does my breastplate shine

Nor does my silver comb gleam

As they did in years gone by,

Even the summer before last.”

Women can be not only vain, but crafty. Mataleena lies when she first encounters Jesus at the well:

Jesus walked among the willows,

Stood like a shepherd on the scorched earth:

“Give me water to drink.

I have no vessel to hold it.

Pour the water into my hands,

bring me big handfuls.”

Mataleena, who is proud of her birth, scoffs at the poor shepherd.

“Nice thing for you to say, oh Finnish lad,

Finnish lad, slave in the fields,

My father’s shepherd for all time,

You who have subsisted on Swedish crumbs,

Brought up on fish heads.”

At this point Jesus reveals that Mataleena, who claims to be a virgin, has given birth to and killed three baby boys.

I will remain a Finnish lad,

Finnish lad, slave in the fields,

Your father’s shepherd for all time,

Who has subsisted on Swedish fish bones,

Brought up on fish heads,

As a shepherd on scorched earth,

If I keep your deeds secret.

“Say everything that you might know.”

“Where are your three little babes?

One have you thrown in the fire,

One have you tossed in the water,

One have you buried in the soil.

The one you threw in the fire,

Was not a knight in Sweden;

The one you tossed in the water

Could have become a gentleman

The one you buried in the soil

Could well have become a priest.”

Mataleena breaks down when confronted by these reproaches and accusations:

The young maiden Mataleena

Was finally seized by tears of regret,

Which filled her pail to overflowing,

And she washed Jesus’ feet,

And dried them with her hair.

“Are you Lord Jesus himself,

who has spoken my ill deeds?

Let me lie, Lord Jesus,

Like a corduroy road in the marsh

To be tread upon over and over;

Let me lie, Lord Jesus,

Lie wherever you please,

Float like driftwood on the sea

Soaked by the waves;

Let me lie, Lord Jesus,

Lie wherever you please,

Lay me like a piece of coal in the fire,

Lay me like a fire in the hearth

Flickering in the wind,

Dying among the embers.”

Aesthetically speaking, the ballad is one of the most brilliant examples of popular Finnish poetry. Ideologically speaking, it is in the long, tenacious tradition what regards women as sinners and violators of sexual morality. Thus the same rite of spring included the ballad of Annikainen, whose ethically challenged seducer meets a grim fate, and the ballad of Mataleena, who must accept all the guilt for sexual indulgence. Popular morality spoke in many tongues.

Translated by Gaye Kynoch