The men of the Modern Breakthrough saw naturalism as a scholarly paradigm – for Amalie Skram it became a passion!

Since Mathilde Fibiger’s day, the nonsynchronism between men and women had rendered knowledge the ultimate goal for women. They had been denied access to the humanities-based Latinskoler (grammar schools), and study of the ‘new’ science subjects was also a male prerogative. However, change of the scholarly paradigm from idealistic-speculative to materialistic-analytic put women in a completely new position – because observe, that they could! And they could even do so without examination certificates! The modern scientific methods, which were applied by scholars and artists alike, relied on: observation. Naturalism – “[a] work of art is a corner of nature seen through a temperament,” in the words of Émile Zola – was, in principle, open to everyone irrespective of gender and class. If, that is, the writer had eyes to see and enough immodesty to look – this being the delicate point: no one would expect men to avert their gaze from the realities of life, but for a woman to step across the threshold of modesty took not only courage in the normal sense of the word but also a driving passion that few could muster.

“Once the woman has risen,” wrote Amalie Skram enthusiastically in 1880 of Henrik Ibsen’s Et Dukkehjem (1879; A Doll’s House), “she can no longer be stopped.” And stop – that was not on the agenda of Amalie Müller, as she was called at the time. She was carried away by the new ideas about freedom, about nature, about literature that shows itself to be alive by putting “problems under debate” – and she was in possession of the passion that “annuls all else”.

In 1884, Norwegian Amalie Müller (1846-1905) married the Danish writer Erik Skram and moved with him to Copenhagen. And this is when she began writing in earnest – but she was never really akin to the Danish women of the Modern Breakthrough: her passion set her apart. Even though most of the women writers were influenced by the naturalistic school of thought, and to a greater or lesser extent flirted with the naturalistic ‘stylelessness’, their pens displayed a restraint, a self-protective reservation that was alien to Amalie Skram. While other women writers put themselves on the outside, Amalie Skram related totally to her material – with ruthless exploitation and self–exploitation. The blasé attitude versus the passionate attitude. In this passionate intoxication, Amalie Skram did what no one else could do at the time: she rendered the naturalistic method as art!

Amalie Skram’s friend, Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson, made a sharp diagnosis of her nature in a letter dated 1 May 1884, written to her on the occasion of her marriage to Erik Skram:

“[…] does Skram know you? […] Does he know that you have, and seek your strength in, an awfully sensuous disposition, in food, in colours, in drink, in sexual drive and affect not to be so! […] Does he know that you are the most timid, most vain person one can hound and harry, – are the bravest, most selfless candidate for martyrdom as well?”

As creative artist and woman, she was in an outsider position. Too intense for her Danish colleagues, with whom she actually shared faith and hope – categorically blacklisted in Norway, where women writers found a forum in Norsk Kvindesagsforening (Norwegian Feminist Association) and vigorously disavowed the ideas and view of creative art manifested in naturalism. By virtue of this exposed position, however, she was the very embodiment of the zeitgeist and everything about which the others were also writing. She was a vulnerable little lass who never felt accepted or acknowledged; a beauty with the whole world at her feet; an author who wrote from the depths of her heart – a madwoman and an upstart.

Amalie Skram was born Berthe Amalie Alver in Bergen, where she grew up. Her father had worked his way up to running his own small business. Amalie herself continued this rise up the social ladder through her marriages. At eighteen years of age, she married an affluent ship captain, August Müller, and after their divorce in 1877 she became involved with the literary bohemian milieu; marriage to Erik Skram gave her admission to the Brandesian inner circle. The author Amalie Skram thus came into being via breaking up. Breaking up with her childhood setting, with marriage, with religion, with her homeland – and with ‘woman’. She was quite exceptionally unaware of a woman’s place; she behaved just like a man: drank everything in with open eyes as she sailed the oceans and explored the harbour hangouts of the world with her first husband, the ship captain; held forth on religious and literary topics in the daily newspapers – always riding high, beset with indignation and admiration.

Amalie Skram was so unacquainted with the woman’s place that she was one of the first authors – man or woman – to live from her writing, on the terms of the market. Being a parvenu, she had moved between extremes: between her modest home and the exclusive school that her mother got her into, between the Romanticism of her school books and the realism of the Modern Breakthrough, between Norwegian village culture and European city culture. As an author, she also lived at the extremes. Huge self-esteem shifted abruptly to dark despair.

From Amalie Skram’s letter to Sophus Schandorf, dated 4 December 1889 – there is nothing wrong with her self-esteem here:

“To Venner is a good book; ‘Politiken’ not being able to see that will not make it any less good.”

Given that there was no veneer of old culture to give her protection, her writing was as porous as blotting paper: susceptible to every change of climate – of mind and of zeitgeist.

Amalie Skram’s Naturalism

While the majority of Danish Breakthrough women put all their artistic efforts into writing what was unspeakable, Amalie Skram’s pen utterly denied the existence of the unspeakable. Where others endeavoured to seize the transience of the moment by means of inference, her intention was to wring the moment of its absolute truth by saying – everything. Unlike resolute impressionism, which ‘prunes’ reality, Amalie Skram cultivated an “aesthetics of multiplicity”, in which she endeavoured to drain the meaning from the slice of reality she was describing. Everything the eyes see, the ears hear, the nose smells, the nerves sense, is in principle verbalised: “The hand holding the broom dropped dejectedly. The eyes were so strangely vacant, and a dark sallowness lay across the face. She started to walk, but staggered and grabbed hold of the window post. She stood momentarily, blinked a few times, dried beads of perspiration from her mouth with the back of her hand, helped her to breathe again, and then set forth.

“She took the mewing twins from the boy, sat down on a box out in the alley, and set them to suckle at her empty breast. The man had propped the two lame children against the wall on a pile of dirt, over which he had spread a cloth. The others slouched timidly and famished around their mother.”

This passage is taken from Amalie Skram’s literary debut, the short story “Madam Høiers Leiefolk” (Madame Høier’s Lodgers), published in 1882 in the Norwegian literary, cultural, and political magazine Nyt Tidsskrift. A sardonic description of the tight-fisted and cynical Madame Høier and the wretched setting – a kitchen behind the stables, which Madame Høier has “turned into family accommodation for humble folk” – is followed by a story concentrating on one day in the life of an unemployed couple with eight children; the day on which they are literally turned out on to the streets. In the passage quoted they are being evicted, and the woman in the scene is the mother, who has recently given birth to “a set of bluish-violet twins”.

The story differs from her later writings in its mocking tone that distances narrator from material. But the choice of material and the analytical scrutiny is found throughout Amalie Skram’s oeuvre. Physiognomies, modes of expression, and interiors are ‘microscoped’ with meticulous precision: not yellow, but “dark sallowness” – not vacant, but “strangely vacant” – not with her hand, but “with the back of her hand”. Nor does the woman simply walk outside, no, every moment of her progress – from her stagger to her breathing – is included. There are no clear-cut colours or lines. We are, on the contrary, presented with muddy shades and a series of downward movements – “dropped”, “dejectedly”, “staggered”, “sat down”, “slouched” – which, in more than one sense, move towards the “pile of dirt” that is the fulcrum of the setting. Distinctive to this kind of illusory reality is the merging of narrative time and narrated time – but ‘time’ is simultaneously exploded as progressive sequence. Time does not exist as orientation, but as momentary deflections caused by random irritations and impulses – from outside or inside the body. Next to nothing is told, meaning is shifted from fable to setting, from concept to material reality.

This debut secured Amalie Skram a ‘seal of approval’ as modern and degenerate. In the newspaper Bergensposten (Bergen Post), a reviewer lumped her together with “the crassest realism of the day”, and she was held up as a scary deterrent – the delusory woman who “gets far more vehement than a man […] and in her depiction feels able to include things that a man would feel bashful and repelled to express” – which caused Amalie Skram to gloat to a female friend: “Only things that are any good are the target of attack.” Because she was not going to be stopped – and certainly not by reactionary forces.

The hue and cry provoked by the story was partly the result of its writer immodestly acknowledging authorship under her own – female – name. Madonna had descended from her pedestal for all to see, and angel-dust had been replaced by dirt – indeed, she was wallowing in filth.

From “Karens Jul” (1885; Karen’s Christmas) – Amalie Skram’s naturalistic construction of ‘Madonna and Child’:

“They were both stone-dead. The baby lay up against its mother, in death still holding her breast in its mouth. Down its cheek had trickled from her nipple some drops of blood, which clotted on its chin. She was terribly emaciated, but on her face there was something like a quiet smile.”

Drunkenness, lasciviousness, poverty, hunger, grime, and meanness were of course not unknown quantities, but they were not anything literary works were meant to discuss – and certainly not in this concentrated manner. And it was absolutely not something a woman should address – far from it – she should point upwards, away from the dirt.

Amalie Skram’s debut publication was thus a frontal collision between Romanticism and realism. She had been seized by the ‘horizontal’ forces, the ones that subverted hierarchies, values, opinions. And, with the hypersensitive alertness of the social upstart, she became obsessed with modernity. The detritus, the rendering random and anonymous of human nature, went straight into her pen. She had no defence mechanisms against the bombardment of her senses. Thus, her style was so ‘packed’ in a desperate endeavour to keep abreast of the impressions. The torrent of detail corresponds to the feeling of drowning in the swarm – stabilises, as it were, the porous structure of her personality with a semantic structure. By being particularised, the detritus becomes manageable.

Dirt

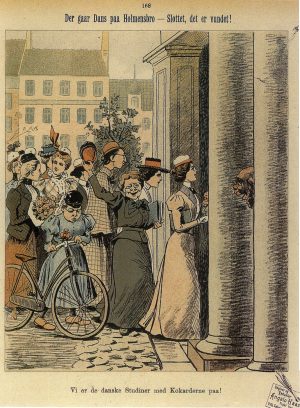

During the Modern Breakthrough in general and the public debate about moral standards in particular, literature became a kind of ‘social broom’ sweeping prostitution, double standards, and all sorts of dirt out of the nooks and crannies. Breakthrough literature written by women did not hold back – on the contrary, it was largely due to the women that the connection between an inhibiting girls’ upbringing and the double standards was brought out into the open. It seemed that everything could be written about except, that was, one thing: the dirt produced by the female body. That the servant girl took care of the coarse and material aspects of existence, and that someone did the cooking, emptied the toilet pan, did the laundry, and polished the boots, was a tacitly understood absence in most of the modern literature written by women. If servants did put in an appearance, it was in the role of disquieting otherness, as a different and semi-animal race. It is also worth noting that however desperate the women writers’ circumstances, however impoverished they might be – they all had a maid. This was one of the necessities of life that could not be questioned.

These accepted truisms of the times were shared by Amalie Skram. And yet not. It had not escaped her notice that her mother had started out as a lowly servant girl; this had a lasting influence on her works – on the themes and perspectives. And thus, during her most productive period, between 1884 and 1892, she wrote a series of novels and novellas in which she did indeed address the same themes as the rest of the Breakthrough women writers – girls’ upbringing, suppression of sexuality, marriages of convenience, and double standards – but, unlike them, she included the dirt. In Amalie Skram’s novels, the physical woman and the cultural woman not only function as mutual contrasts, but also as mutual reflections. As in a distorting concave mirror, they contemplate themselves in the other, yearn for themselves in the other, and run away from themselves in the other. For they can never reach one another. As if staring through a window, Constance in Constance Ring (1885) surveys the kitchen, the domain of the serving girl, and sees “a bit of enchanted land”, whereas the serving girl gawps inquisitively through the keyhole at her mistress’s strange behaviour.

From Amalie Skram’s Constance Ring (1885) – a maid’s glimpse into her mistress’s world:

“Once in a while Johanne would have an urge to know what in the world she was doing in there hour after hour, and she would peek through the keyhole. Often she would see the mistress sitting bolt upright, a shoe in her hand and one foot resting on her other knee. […] After awhile, when the silence inside made Johanne suspicious, she would again creep up to the keyhole in her stocking feet, and there the mistress would be sitting in the same position, except now she was in a trance over her other foot.”

In the novel Forraadt (1892; Betrayed), the reflection occurs in the other – corporeal – woman via the husband’s confession. It is only through verbalisation of her husband’s escapades that Aurora can – trembling – get into imaginary contact with her own body.

Amalie Skram is definitely no Romantic, and in her works there is thus not even the slightest attempt to idealise the maid as being more wholesome and ‘genuine’ than the women of the bourgeoisie. When servant girl Alette allows herself to be seduced by Constance’s husband, she does so because her sexuality is functionalised and imperialised by the very other, that which is behind the window – the “appealing smell of fine gentleman” and soft hands. Similarly, the former “Tivolipige” (in this case, a young woman who worked as a dancer at the Tivoli pleasure gardens in Copenhagen; and here also a euphemism for a woman of ill repute) in the novel Lucie (1888) is aroused by a lawyer, Theodor Gerner, because sensuousness and social prestige are intertwined in her configuration of drives and instinctual strivings. Neither mistress nor maid has free access to her respective body – their respective sexualities are simply formed or deformed in different ways.

Something Dark, Wet, Slimy…

None of Amalie Skram’s female characters have thus been able to assemble a ‘bodily self’. Alette first arrives in her body once Ring has named it as ‘something’: “a luscious body”. In searching for orgasm – “this mystery of rapture” – the central character in the novel Fru Inés (1891; Mrs Inés) does not connect to the body per se until it is reduced to gory meat: on her way to a backstreet abortionist she is brought up short by the sight of a “dog, skinned alive from snout to tail” with “the inside-out, steaming slough trailing behind it in the dry dust of the street”. She subsequently has a miscarriage and later dies of a violent haemorrhage. In Lucie the female body becomes a real thing which, like the skinned dog, is at the mercy of its assailants. On the verbal level, Lucie’s body is ‘traded’ via the fine young lieutenant’s hypnosis – on the physical level, a rapist deals with the matter.

Be you maid or mistress – it all comes down to the same thing. All are living on the illustration, the staging of ‘bodily self’. Thus, in front of the mirror Lucie puts together a picture which includes various ‘fetishes’ from previous stage-managements of herself – her bridal veil, silk stockings given to her by her husband, a Roman sash from her days on the stage, some cloth flowers, and a short embroidered petticoat:

“‘Masquerade, Queen of the Night, flowing hair’, she pulled up her hair and undressed […] Then she gathered her heavy, golden hair, which reached below the split in her skirt, raised her arms, so that her high, white breast stood proudly forward, tied her hair with a red ribbon at the nape of her neck, stuck in the flowers on the top of her head and pinned the bridal veil over it all, allowing it to fall like a white river all the way down to her feet […]

“She fell motionless and burst into tears, reached out towards her weeping image in the mirror. Yes, she was indeed comely, oh she was comely, but she had never seen it quite as she did this evening.”

Lucie is at home alone, and in order to be aware of herself she has to see herself.

Amalie Skram’s women are hypersensitive – in Lucie (1888), the central character is a reflection of the mirroring surroundings:

“And each time she walked past the big bedside-table mirror on the dressing table, she turned the little head with its golden-grey, vivid hair knotted at the nape of her neck in order to catch a glimpse of her broad, beautiful shoulders and to see if her stomach was protruding in exactly the appropriate manner. And so very white was her skin, with circles on her throat and a delicate, amber flush in her cheeks, like a peach, Theodor said.”

Correspondingly, in Constance Ring Constance has to be masked as the picture of herself – at a masquerade ball – in order to reach an emotional intensity that resembles being in love. Besides double standards and the faithless mothers, Amalie Skram’s women therefore also have themselves to contend with. Their sense of self is rudimentary; self-image must be constantly corroborated from the outside or stage-managed by means of grimacing, unctuous poses.

Like story, like writing – there is no evaluating narrative authority besides Lucie. As is the case here in front of the mirror, almost everywhere in Amalie Skram’s oeuvre the narrator takes refuge behind the characters, the writing is theirs. This makes for a consistently sympathetic presentation, but also a form in which nothing can be concealed. Anything deficient and improper in the characters’ outlook and attitudes is ruthlessly exposed.

In this manner, Amalie Skram depicts conscious mental life as a closed psychological system in which the individual is both left to his or her self – unable to step actively into the outside world – while being defenceless against intrusion from the outside world. The individual is like a tourist in the real world. Everything is reflected, but there is no exchange between person and surroundings. The consistently indirect style precludes dialogue.

Amalie Skram’s novels therefore do not speak of development, but of instinct. Of instinct as an impersonal ‘something’ that possesses the defenceless victim – like Riber in Forraadt who, as a result of his wife’s ruthless pursuit of his past, ends up just as naked and nebulous as the spectre that emerges in his hallucinations: “Something dark, wet, slimy, which suddenly appears in broad daylight. Its colour resembles the skin of a seal, but in shape it is neither animal nor human.”

Even though the characters construct their lives on the basis of a Romantic notion of love, this love thus has straitened circumstances in the marriage novels. On the other hand, they register with almost seismographic accuracy the changes that took place within the relationship parameter during the Modern Breakthrough. While members of the Biedermeier family had represented an ideality that reached beyond the individual – the concept of Woman, the concept of Man – sex now became a bodily, private matter. This made for a new freedom, a greater sense of self, but also involved the danger of losing oneself entirely if the other person reneged. Amalie Skram’s novels tell of the vulnerability that developed within the eroticised relationship. The novels Bøn og Anfægtelse (1885; Prayer and Temptation) and Knut Tandberg (1886) both depict couples in which the sexual relationship has run dry, with lack of identity and madness taking over. The parties have sought out the intense pleasure of life in one another, and once that cup has been supped, only the dregs remain; there is nothing that reaches beyond them as individuals – not even the children.

From Amalie Skram’s Knut Tandberg (1886) – modern maternal feeling?

“Therefore she simply could not be fulfilled in the children, as she knew people expected a mother should. […] But how could she, she with this constant ache of dissatisfaction and privation […] When Knut had loved her, all her pleasures had come to her through him.”

For Amalie Skram’s forsaken women, the maternal feeling is tangled up with an eroticism that is an end in itself. Should the husband’s love burn out, the children lose their value. Accordingly, in both these novels the children are superfluous – or hostages in the adults’ game. Sometimes the adults attend to them with forced jollity, sometimes they bite their ears off. In the case of Bøn og Anfægtelse, we have a father who is not only unstable in a general kind of way, but is actually insane – which serves to highlight the perspective: in Amalie Skram’s universe, the adult is a mysterious factor in the face of which the child has no defence. Mother and father alike are fully occupied safeguarding their own minimum level of survival; to the child, therefore, the laws governing reciprocity and love are unpredictable – insane. The women are parvenues in a sexualised gender, and similarly the children are parvenus in the adults’ world.

The Fantasising Child

A child of this type will be broken – or turn into a dreamer. From the outset, with her very first novel, in the midst of all the filth Amalie Skram’s naturalism also includes a fantastical dimension. In a way, all her central characters are children – little, undeveloped human animals who can only enjoy or suffer, but never by means of action or volition do they come abreast of their reality. And thus, given that they are childlike, like children they can fantasise themselves away from the exposed condition in which they actually exist. Look at Lucie in front of her mirror – she is in the middle of a comic game which then turns into tragedy when she steps out of the fantasy, lets it harden and become a mask. Throughout all her writing there is this undercurrent of dream, fantasy, and madness, and it was on this creative energy that Amalie Skram wrote her major work: Hellemyrsfolket (1887-98; The People of Hellemyr).

The conservative Norwegian newspaper Morgenbladet showered criticism upon Sjur Gabriel (1887) – the first volume of Amalie Skram’s Hellemyrsfolket (1887-98; The People of Hellemyr). The sequel, To Venner (1887; Two Friends), however, received even rougher treatment on 29 November 1887:

“Her fountain in respect of ‘abomination’ would seem to be inexhaustible. With all its choice collection of filth, there was nonetheless an element in this respect which was missing in Sjur Gabriel: the offensive […] In the current book the authoress has made up for lost ground, and reviewers in the Liberal press would, of course, think that she has rendered this with the same ‘discreet’ artistic skill that they praised in her previous book.”

Hellemyrsfolket is a family saga tetralogy, but it is also a monumental portrait of the modern dreamer and parvenu. In Sivert, who enters in volume two, To Venner (1887; Two Friends), and assumes a central position for the rest of the work, Amalie Skram has created a character who contains her own extremes: spanning the upper and the lower classes, the adult and child, man and woman – and, above all, spanning the prison of the facts and the freedom of the imagination.

Sivert is a fantasist, but he makes reality comply with his fantasies – for a while, at least. On the one hand, he can cope with the incredibly harsh and brutal reality in which he exists because he fights back: in To Venner he steals from his credulous patrons, in S. G. Myre (1890) he kills his drunkard of a grandmother and steals from his employer’s till, and in Avkom (1898; Descendants) he continues his shady career with petty crime and counterfeit money. On the other hand, however, all this is something he has almost effortlessly ‘come by’, because the reality has actually already arranged itself according to his fantasies.

In the fictions he creates, Sivert keeps himself suspended above the abyss between falsehood and truth; if he gets in a fix, he has enough capability of life to inject reality with a fantastical dimension that he convinces himself he believes in. And in this way he makes himself believe it was out of love that he proposed marriage to Petra – housekeeper for the grand consul Smith – which, truth to tell, is pure fiction. When he was fifteen years old, he had in all innocence allowed himself to be seduced by his then employer’s daughter, Lydia. She – or rather, the affluence she represents – is the object of his desire, but he cannot have her. Petra, on the other hand, is a socially suitable match – she is the consul’s ‘used’ mistress, and when the consul wants to marry Lydia, he offers Sivert the prospect of a shop – if, that is, he takes on Petra. Faced with Petra, Sivert’s fictions no longer hold water. She becomes his prosaic reality, which cannot be rewritten; what was previously fantasy becomes downright lying, and Sivert ends up in the debtors’ prison, where he dies.

In Hellemyrsfolket fantasy cannot traverse the abyss between the social classes – overstepping the naturalistic ‘truth’ takes place at a different level. Sivert’s fictions are the nucleus of the tale, all the good stories in which the work abounds. He is no better or cleverer than Amalie Skram’s other characters, but he is far more fascinating because he is constantly on the move – between the classes, between the sexes, between lies and truth. Always just about, just about… Suppleness and suspense emanate from his being, lending lustre to the raw material and the far from uplifting story.

With Sivert taking the lead, the work is more than a naturalistic novel about money and sex in nineteenth-century Norway. It becomes an imaginative web of social realism and folktale, history and fantasy. This causes erosion of the boundaries – between beauty and ugliness, goodness and cruelty. There is no moderation in Hellemyrsfolket. It is an intoxicated and intoxicating work that oversteps its own naturalistic cognitive horizon.

Amalie Skram’s Hellemyrsfolket paints a picture of the grotesque life on the streets. In the second volume of the tetralogy, To Venner (1887; Two Friends), in particular, the coarse bodies and the robust merriment crowd in around the drunken Oline:

“Just at that moment, the huddle of humanity began to move, the circle opened up, and he saw Tippe Tue with something in his hand, something he dragged along the street, and arm-in-arm with Oline he staggered towards him […]

‘Come alon’ with us, Sivert! Tippe Tue and Smaafylla [Tipsy] are goin’ to the pawnbroker to sell her petticoats for a dram!’ bawled a lad’s voice after him.”

Things Take Over

At points in the final novel of the family saga, Afkom, a different script creeps in – mysterious phenomena appear, without any questioning of their actual existence. Similarly, the ingenious structure of the plot, in which Sivert’s and Smith’s offspring match up along almost legendary lines, takes on a ritual significance that pushes against naturalism’s sober consideration of things. The writing begins to live its own secretive life – the writer can but follow along.

In the collection of stories Sommer (1899; Summer), written concurrently with Afkom, things have taken over. Body fragments removed from their totality – “this ugly, self-righteous neck”, “eyes […] ugly and dead like fishglue” – fill the human vision, and in “Det røde Gardin” the curtain and the fly become sinister, hyper-realistic forms that appropriate the body and the text and ultimately eliminate the human subject.

“Det røde Gardin” (The Red Curtain) in Amalie Skram’s collection of short stories Sommer (1899; Summer) – a horror story in which the creepy-crawly takes over:

“All of a sudden he noticed an enormous, greenish fly crawling up under the red crape onto her breast. It had to be removed. Had to. She, who had had such a vivid loathing of flies and all manner of creeping things. But how could he get hold of the fly? He could grasp it between his fingers and squeeze it to death, but then she would have this carcass on her poor, dear body.”

Sommer was written at a time of personal crisis – the Skrams were drifting apart, and in 1899 they divorced – but the stories are also written from a fermenting energy that searches dimensions of the psyche unseen by the naturalistic microscope. Symbolic dimensions, in which the bright-as-day central perspective viewpoint is displaced, and in which the ‘mad visions’ are not covered over by, but are accorded the same footing as, a realistic setting. Macabre formations of suffering and joy, decay and blossoming.

The writing in these stories is at one and the same time expressive of the symbolist current of the 1890s, which had succeeded the 1880s’ naturalism, and also of a completely different kind of modernism. A surreal visual landscape in which the idiomatic prose has yielded to a chanting, hymn-like tone.

No, there was no stopping Amalie Skram when literary art called. Following her divorce, however, the burdens had become far heavier. She had to provide for herself and also for her fifteen-year-old daughter, and the work of writing did not strike her as getting easier as the years went by. Out of necessity, she entered into a contract with the Gyldendal publishing house by which she was paid a regular monthly salary, but in return she had to deliver a specific number of pages from her novel-in-progress, Mennesker (1905; People). And it broke her! With her irrepressible will to live, she would have been able to cope with everything: gossip, the savage criticism – indeed, even the perpetual lack of affirmation and support from her friends. But, if she did not have total freedom to take the time it took to breathe life into her characters, then she could not write. For Amalie Skram, life and fiction was one and the same thing. If she lost her ability to work, she lost her identity. Work was the centre of a life that was otherwise marked by the parvenue’s restlessness and loss of consequence. Amalie Skram had once before been on the verge of losing her sense of self, but at that time she had written herself out of the crisis. This time there was no enemy of a Knud Pontoppidan’s stature, so now her introversion got out of control. The fear of insight, which came in the wake of the controversy surrounding her person, made her peculiar and withdrawn, and she did not manage to work her way out of this state again before her death in 1905.

Amalie Skram was a convinced naturalist; she saw herself as a scientist in the service of truth, and she defended her “sordid scribblings” by drawing parallels between art and science: “No one could take it into their head to hold, for example, a medical professor […] responsible for the comfortless information he must present in the lecture hall.” But she was so officious that she – as has been written – became “far more vehement than a man”. Even good friends such as Bjørnson complained of the “fetid air” in her books.

“I cannot bear the fetid air in your books. Everything you say is true, it is just never enough. That extra which supports life and makes it tolerable (and without which the other would not exist, for the other does not exist of itself, but of that which you do not include) you must rise to include it,” wrote Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson to Amalie Skram on 5 April 1893.

She did not simply settle for reducing existence to its elementary matter in her writing, she proceeded to analyse the psyche – spelling it out in its elementary components and its instinctive processes. And if the realistic setting seemed “vehement”, the psychological setting was yet worse. The structure of imagery in her texts is a continual variation on the same infernal enclosure into which humankind is cast – without use of limbs, without speech, with no possibility of escaping the horrors. Amalie Skram’s stories are just as passionate studies of the depths of the mind as those of her contemporary, Freud, and her body of works thus goes beyond the Modern Breakthrough – towards the madness and knowledge of the twentieth century.

Translated by Gaye Kynoch