The literary career of Aurora Ljungstedt (1821-1908) was shaped by the development in the 1860s of the family journal. The greatest part of her popular writings, which were published in nine volumes in the period 1872-82, consists of short stories, sometimes put together to form a greater whole thanks to a recurring gallery of characters, as for example in Dagdrifverier och drömmerier (1872; Idling and Dreaming).

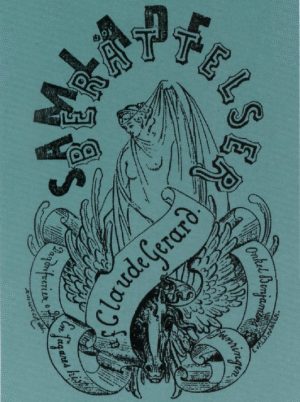

Aurora Ljungstedt’s most used pseudonym, ‘Claude Gerard’, is taken from one of the Paris novels by Eugène Sue, and she may be said to have further developed in a psychological direction the tension-creating serial novels of the 1840s, with their lost letters, foundlings, scheming scoundrels, and mysterious events. Aurora Ljungstedt’s plots are always well crafted, and she meets the public’s demand for vice to be punished and virtue rewarded. In her three big novels, Psykologiska gåtor (1868; Psychological Riddles), Jernringen (1871; The Iron Ring), and Inom natt och år (1874; Within a Night and a Year), she bases herself on the same motif as Sue, a family’s fight over an inheritance, but in contrast to him she aims at showing how money corrupts – especially men. Women, on the other hand, even the most beautiful and the most cunning vamps, are described as victims of social conditions and of their fatal sexual power of attraction. In Ljungstedt’s last novel, Inom natt och år, one notices an increasingly female perspective, above all with regard to the number of female protagonists and the fact that two good heroines eventually win the game as well as the love of the two heroes.

Aurora Ljungstedt’s first novel, Hin ondes hus (1853; The House of the Evil One), was published under a pseudonym in Albert Bonnier’s successful library of novels, Europeiska följetongen (The European Serial Novel). Hin ondes hus makes use of horror-Romantic elements borrowed from Ann Radcliffe’s The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794) but is actually a psychological thriller. The novel is sophisticated in its narrative technique. A young man explores the secrets of a haunted house and communicates to the reader the contents of an old manuscript – which turns out to be an incestuous love story. The male perspective in the narration gives the author the opportunity to make ironic, but not gratuitous, remarks about the period’s gender roles: “Women like that, who in such unblushing manner show that they have nothing to lose, always displease me.”

The fictive male narrator also legitimises a love story of a sadomasochistic nature, which is remarkably erotic for the period. In a triangle drama involving strong elements of jealousy, the female desire is revealed as both criminal and destructive. The young Anna, whom Baron Edvard has married, without knowing that she is his natural daughter, is so erotically enticing that her father, dazed with desire, consummates the incest, despite the fact that, on the wedding day, he has learnt the truth. At a later juncture he kills her – in one of the most passionate embraces found in nineteenth-century Swedish literature:

“Edvard felt this lovely, supple creature gently nestling against him, felt her arms pressing him ever more fervently towards this soft, half-naked breast that heaved with sobs, felt her heart beating against his, her warm breath fanning his face, her lips seeking his, and the gaze of her eyes, tender and voluptuous, glimmering through tears, sparkling into his own; he felt his strength weakening, his senses muddling; on his pallid cheeks glowing hot flames were kindled, she was no longer his daughter, she was Anna – his mistress – his spouse; – instinctively he pressed her towards him, bent down, and brought his starving lips closer to the warm, tempting dunes in his arms … but – suddenly overcome by the dizziness of love and terror – crazy with passion and fear, he grasped the dagger on the floor, a pale blue flash lit up the room, the fine, thin steel forced its way sharply and firmly to Anna’s heart. She slid out of his arms onto the floor: the kiss of death, instead of that of the bridegroom, had met her breast.”

Edvard goes insane, and only when the first-person narrator of the novel has finished reading his story is he able to find peace and atonement in death.

In Aurora Ljungstedt’s ample production of novels there are examples of pure horror Romanticism, such as in En jägares historier (1861; A Hunter’s Tales), but also skilfully written crime stories, as in Onkel Benjamin’s album (1873; Uncle Benjamin’s Album). Her often colourful female criminals and drab male criminal investigators reflect general tendencies in the period’s crime literature. In the early crime story, the main focus lies on the criminal, and not, as in the later detective novel, on the detective, and the final revelations are, rather, a result of luck.

Aurora Ljungstedt creates a suggestive tension. She describes the characters in the novels as slaves of their passions, of an implacable destiny, or of someone’s devilish schemes, in a way that makes one think of the modern thriller.

Translated by Pernille Harsting