Kamma Rahbek was not easily persuaded to visit Friederike Brun’s salon at Sophienholm. Once, when she had to attend a wedding celebration, she allied herself with Oehlenschläger so as not to feel too lost: “I had prevailed upon Oehl. to be there too [the next day], and we two had much fun together”, she wrote to her friend Anna Drewsen in a letter dated 7 August 1815. Oehlenschläger was not particularly at ease in salon life either. In Levnet (1830-31; Life), he writes of his 1806 visit to Berlin: “As much as I might have been associated with Reichardt [a German composer], in that he it was who acquainted me with the great Berlin world, it did not please me for long, according to my nature, to be a kind of intellectual pumpernickel, or Nordic rye bread, at their tea parties. I primarily cultivated those acquaintanceships where I found a home, which has always been so indispensable to me.”

After he married Christiane Heger, Kamma Rahbek’s sister, Oehlenschläger (1779-1850) led a quiet life. His daughter writes:

“My father led a most regular life, preferably without deviation from his routine. In summertime he arose at half past seven, in wintertime at eight o’clock […]. Once he had washed and brushed his teeth, he would dress in a robe not always worthy of a King of Poetry. He then drank a cup of tea and ate a rusk, whereupon he sat at his desk.”

Marie Konow: Nogle Barndoms- og Ungdomserindringer (1902; Selected Reminiscences of Childhood and Youth).

A home was exactly what the salon was not. The salon was a forum in which something had to be accomplished: Oehlenschläger could always read aloud from his own works; Kamma brought along her elegant conversational skills and her celebrated flower arrangements; Friederike’s daughter, Ida, could sing and pose in the so-called “attitudes”. Guests became audience for one another’s performances and were appraised according to their ability to render and enjoy art. Domestic life in the form of intimate fellowship was of no interest to a salon hostess such as Friederike Brun. She thus also had a casual attitude to her marriage with Brun, and paid all the more careful attention to her relationship with a kindred spirit, the Swiss writer Karl Viktor von Bonstetten (1745-1832). She saw the task of a mother to be that of introducing her children to the world of art and the humanities. While they were very young, she happily left them at home with their nanny, later becoming far more involved with their education.

The salon hostess was the exact opposite of the traditional housewife, and the salons extolled a view of women that was in complete opposition to that of the patriarchal family. Having instituted the salon concept in seventeenth-century France, les précieuses disavowed the old Christian view of the man as a human being created in God’s image, half body and half soul, while the woman was more body than soul – and therefore an inferior human being. Les précieuses were of the opinion that the body cannot be ascribed pivotal significance because all the non-reproductive organs are identical in the two sexes, and because resolve and reason are independent of the body. Moreover, the difference in the sexes has no bearing on the life of the soul after death. Angels are non-gendered, they claimed; in the true life, the life of the soul, men and women are equal.

A Swedish Enlightenment writer, Thomas Thorild (1759-1808), wrote an essay “Om qvinnokönets naturliga höghet” (1793; On the Natural Elevated Status of the Female Sex), in which he comments of women: “[…] They must, one supposes, be considered as human beings before being considered as women?”

These ideals of equality were carried forward by Enlightenment writers, but they were incompatible with the existing division of labour between the sexes upon which the patriarchal family had always been based, and which – for the man – the middle-class separation of home and workplace merely reinforced. This division of labour underpinned an ideal of difference: belief in an absolute polarisation between male and the female nature as encapsulated in the physical differences.

Nineteenth-century woman thus faced the difficult task of interweaving two extremely different notions of gender and uniting the best aspects of salon- and housewife-culture. The endeavour succeeded in the Romantic intimate sphere in the light of two crucial circumstances.

Firstly, the culture of the intimate sphere was a middle-class one upheld by a limited family circle. As the man’s workplace moved out of the home into public offices, school classrooms, or army barracks, the women could take over the home as their domain. It was only at the rare social dinners, when the “hall” was opened up and the table laid, that the master of the house was still to be seen representing the family within the four walls of the home. With the less strenuous management of the house, the housewife had the possibility to create an independent domestic culture that was separate from the ‘entertainment’ required by considerations of status.

Secondly, the Romantics developed a pantheistic theology that installed women in the symbolic order in a completely new and crucial manner. The Romantic Movement, which was a leading force in the early years of nineteenth-century Europe, was fundamentally a secularised reinterpretation of the Christian myths, which the rationalism of Enlightenment philosophy had tried to stamp out. There was no longer a God the Father out there in the universe; instead, the divine was seen in nature, a concealed design that the brilliant individual – the poet – who is part of this nature, is able to grasp intuitively and then express. Philosophers of the Romantic Movement put man, the poet, in God’s place: “Every good man becomes more and more God. To be God, to be human, to evolve are synonymous terms,” wrote a chief Romantic ideologist, Friedrich Schlegel, in 1798 in one of his Athenäums-Fragmente (1798-1800; Athenaeum Fragments). As was the case before God, the man was now creative in relation to nature, and the prototype for his interaction with nature was union with the woman.

Friedrich Schlegel (1772-1829) was also much celebrated for his novel Lucinde (1799; Lucinda), in which the Romantic ideology of the intimate sphere is expressed thus in reference to the lovers: “They were the universe to each other.”

The Romantics thereby gave woman a new and more significant position in the symbolic order: the position as ‘the other’. The man’s new female opponent and partner also borrowed radiance from the ‘Madonna’ image that had been in constant growth since the days of medieval troubadours and mystics. Woman was idealised, in an almost religious sense, as an original form of nature and seen as the antithesis of the man, his unconscious non-self with whom he could experience the healing of individuality and create a synthesis, a third person, the child.

These social and ideological features, which became prevalent in the European transition from eighteenth to nineteenth century – the establishment of the middle-class family as culture-bearing and the Romantic idealisation of woman as partly the mother of God and nature and partly the unconscious and alien aspect of the man’s humanness – contributed to a union of the previous periods’ female types, the housewife and the salon hostess, in the woman of the Romantic intimate sphere. In this way, Romanticism gave the woman a cultural position by virtue of gender alone – a position which she had not had before and would soon lose again.

The Romantic intimate sphere was, unlike the salon, a home, but not therefore simply a (petit) bourgeois nuclear family. It was a community of the sexes, which would realise the Romantic philosophy and religious attitude to life. By absorbing and conveying inspiration from the wider European movement, women’s literature played a key role in structuring this new identity of the intimate sphere.

Farewell to the Eighteenth Century

The difference in love between the sexes during the final sensitive decades of the eighteenth century and during the Romantic nineteenth century was a key reason for Danish literature’s most famous divorce: between Thomasine Gyllembourg (1773-1856) and Peter Andreas Heiberg. The circumstances surrounding their divorce became public knowledge a generation later when Thomasine Gyllembourg’s daughter-in-law, Johanne Luise Heiberg, published her account of the sequence of events, underpinned by an extensive collection of letters, Peter Andreas Heiberg og Thomasine Gyllembourg. En Beretning, støttet paa efterladte Breve (1882; Peter Andreas Heiberg and Thomasine Gyllembourg. An Account, Supported by Surviving Letters). One situation from the affair will serve to illustrate the character of eighteenth-century sensitivity and its limitations, as seen through a woman’s eyes.

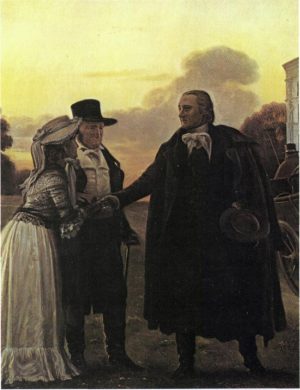

Having contravened the censorship laws, Heiberg had been banished and had to take his leave of Denmark just as the new century began. On the day of his departure, 7 February 1800, his inner circle gathered for an evening party at Heiberg’s home. The mood was understandably gloomy, albeit Heiberg himself was in good spirits because he did not think his banishment would be of long duration. He had not appealed against his sentence, wanting to retain the martyr role in the eyes of the public. His leave-taking with his wife Thomasine and nine-year-old son Johan Ludvig was brief, writes Johanne Luise Heiberg, “apparently without any display of emotions, which, as we know, was not his way.”

However, a little later that same evening, Heiberg actually displayed a most sublime form of sensitivity. He had given Kamma and Knud Lyhne Rahbek a lift in the carriage that was to take him to the ferry in Korsør, to make sure that they got safely home to their Bakkehus outside Copenhagen’s western gate. When his friends got out, as Rahbek writes in his memoirs, Heiberg “possessed himself of one of my wife’s gloves, which he has kept even to this day, honouring it, and has in his correspondence with this his loyal lady friend constantly mentioned up to most recently”. As late as 1827, Kamma was informed that the glove had been placed respectfully in the “Greek box” (a box decorated with Greek freedom symbols) that she had sent him.

The glove story became widely known from the memoirs written by Rahbek and Heiberg. Its form was a typical example of the eighteenth-century culture of sensitivity, in which feelings were linked to individuals or symbols of public import. The glove symbolised Kamma’s hand. She was the grand muse of Danish literature. By means of the glove, Heiberg was thus married to the most distinguished Danish genius, and he was happy to tell everyone about the joy of this ‘marriage’. On the other hand, any private feelings of a less sublimated nature he had for his wife and child, in a more down-to-earth sense, were kept meticulously hidden. In the correspondence concerning their divorce, in the autumn of 1801, however, these feelings came out and, it would seem, took him unawares. It certainly took him by surprise that there were feelings it might be necessary to put into words.

Heiberg’s feelings for Kamma and Thomasine, respectively, were of a completely different type, and it never occurred to him that these could be reconciled. The problem was not that Heiberg lacked feelings; on the contrary, he set aside his entire civil existence in the battle for his ideals: fatherland, literature, freedom. The problem was that his wife could not have a share of these feelings because, as housewife, there was no place for her among his ideals.

Eighteenth-century sensitivity was representative just like the public sphere in pre-bourgeois society. Showing feelings openly gave intellectual power and status. One example of this is Baggesen’s idealisation of woman in the poem “Min anden Skabelse” (1785; My Second Creation), in which he writes about the significance of the poetic speaker’s meeting with Seline:

I saw you as a deity from on high;

And with the stimulation of your smile

My cold self, in the radiance of your eye,

is explained, suddenly given spirit and life.

There are no limits to the qualities attributed to woman in the person of Seline. She is the source of all spiritual and intellectual life in the poetic speaker and opens the whole of nature to his eyes: “Now my days are bound to the Earth, / And nothing is insignificant for me any more.” But in all her infinite sublimity, Seline is less a woman than a symbol of the noblest in humankind, of the ability to feel: “Now I feel, as if my own, the pain of others / And when a brother weeps, I weep too”, we read, and: “Now I have friends, nobles, who sweeten / The lot in life my fate has given.” Seline is an ideal of humankind with whom the male narrator identifies as an object of worship rather than one of love.

Jens Baggesen (1764-1826) also cultivated the platonic glorification of woman in his private life. “Seline” is written to the wife of the poet C. H. Pram; when he was a young student, Baggesen lodged with the Pram family. After marriages, he experienced a new platonic fascination with Oehlenschläger’s sister, Sophie Ørsted.

Although the male writers politely allowed the female characters to carry forward the common ideal, this distinctive eighteenth-century sensitivity was asexual, identical for man and woman. Given that the writers were most often men, a long tradition from both antiquity and Christianity had taught them to project their ideals onto a female figure. Famous examples of woman as representative of ‘the beautiful soul’ are found in Samuel Richardson’s epistolary novel Pamela (1740) and in Goethe’s Wilhelm Meisters Lehrjahre (1795-96; Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship). Richardson had just started compiling manuals on the art of letter-writing for both sexes; in terms of content and form, his letters were to be models for the elegant approach from person to person.

Tears were a sign of the ‘beautiful soul’ and it was completely acceptable for men to weep in public – at the theatre, over admirable deeds on stage, for example. However, in the nineteenth century this sensitivity was, like almost everything else, differentiated by gender, and tears became the prerogative of women. Gender differentiation was part of the same movement that established the intimate sphere, but its design in terms of ideas and its dissemination was largely the work of Rousseau. Though in Julie, ou la nouvelle Héloïse (1761; Julie, or the New Héloïse) we might see him assume the position of Enlightenment philosophy, that the soul has no sex, he expressly adds that “its affections make distinctions between them” (that is, the sexes).

The Idea of the Female Sex

Rousseau was the first to form a theory of gender complementarity, uniting elements of equality from Enlightenment philosophy with elements of difference from the social division of labour. This theory is drawn up most clearly in his major work on pedagogy, Émile (1762; Émile, or On Education), in the concluding Book V of which Sophie is introduced as Émile’s coming partner. Many passages make a modern female reader’s hair stand on end: “woman is specially made to please man”; “after all, why should a little girl know early on how to read and write? […] There are more who abuse this fatal knowledge than use it well […]”; “girls should be vigilant and hardworking, but this is not enough by itself; they should be accustomed to annoyances early on.”; “women being made for dependence, girls feel themselves made to obey”; and, to sum up, woman “has taste without deep study, talent without art, judgment without learning.”

How, we might ask, could an oeuvre with views such as these arouse – as it did – the enthusiastic interest of women. In 1802 Thomasine Gyllembourg writes to her husband: “When I got home, I sat down to read Rousseau, and so engrossed was I in my reading that I was aware of nothing else until the sun had almost set.”

Thomasine Gyllembourg borrowed a little of the plot from Julie, ou la nouvelle Héloïse for her Montanus den Yngre (1837; Montanus the Younger), in which Rousseau’s novel gets a mention as: “the unattainable masterpiece that surely delights every heart.”

We also have Rousseau to thank for Sophie Thalbitzer’s memoirs, which are among the most interesting to come out of the early nineteenth century. Her introduction states:

“From the moment I first read Rousseau’s Confessions, there arose a wish inside me to write something similar.”

The answer is that Rousseau’s ideas of complementarity were a step forward in relation to the two hitherto views of woman: the emancipated woman of the salon, who as “pure soul” was based on a repression of family fellowship, housewife role, and gender difference, and the old patriarchal family’s woman who as “house slave” (as the Latin word “familia” indicates) was subject to an indissoluble, gender-based power hierarchy. When Rousseau starts out by stating that “Sophie should be a woman as Emile is a man”, his contemporaries did not read this as an assertion that the woman should be held (down) in her place, but that the woman had her own place alongside the man. Rousseau also goes on to emphasise that in “all that does not relate to sex, woman is man. She has the same organs, the same needs, the same faculties.” Battle and competition between the sexes is rejected: “In all that does relate to sex, woman and man are in every way related and in every way different.” Reciprocity and exchange are highlighted. The man is the strongest, but he is dependent on the weaker woman, who has a natural gift for managing the man. She obeys his commands, but nonetheless she manages him: “Woman’s reign is a reign of gentleness, tact, and kindness; her commands are caresses, her threats are tears.”

It was later, in the nineteenth century, that Rousseau’s ideas of complementarity were subject to criticism, once mounting individualism made it clear that the woman was left with less individual life than the man: “The male is only a male in certain instances; the female is female all her life,” he writes, for example, and “all the education of women must be relative to men.” The more the man became ‘himself’, the more obvious was the woman’s status as ‘the other’.

Mary Wollstonecraft was quick to come forward with her critique of Rousseau. In A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792) she spends a whole chapter analysing Émile and criticises Rousseau for making woman “the slave of love”.

Core Currents in European Literature Written by Women

Two European women writers in particular, Germaine de Staël (1766-1817) and Jane Austen (1775-1817), fleshed out in words the female types that corresponded to the female positions in the salon- and the housewife-cultures, respectively. The lives of these two authors were just as different as those of their heroines, and their writings had completely different destinies in the Nordic region.

Germaine de Staël was the daughter of Jacques Necker, a banker from Geneva, who was Director General of French finances in the period before the Revolution and eventually First Minister. Her mother, Suzanne Curchod, a pastor’s daughter, hosted salons for writers, diplomats, and nobility. Germaine was thus born into elevated circles, and after her marriage in 1786 to the Swedish ambassador, Baron Eric Magnus Staël von Holstein, seventeen years her senior and without a fortune, she was free to follow her political and literary interests. She gathered together the liberal and philosophical minds of the day in her salon in Paris, until her opposition to Napoleon sent her into exile, partly at her father’s château in Coppet, Switzerland, where Oehlenschläger, among others, visited her in 1808, partly travelling the length and breadth of Europe. Besides political lampoons and analyses, Germaine de Staël’s other works included the first sociology of literature, De la litterature considérée dans ses rapports avec les institutions socials (1800), and an introduction to Germany, De l’Allemagne (1810; Germany), at the time a quite unknown culture in France. She also published the novels Delphine (1802) and Corinne ou l’Italie (1807; Corinne, or Italy); the latter, which led to European fame for its author, in particular, depicts the female type from the salon culture. Corinne was translated into Danish in 1824 to 1825 by schoolmistress Anne Sophie Brandt (b. 1784, d. after 1855), who then issued it through her own publishing house. The subscription list shows that Germaine de Staël had readers among all the notabilities of the land, headed up by the royal family. Ten years later Anne Sophie Brandt wrote a couple of collections of short stories, which she also published herself.

Corinne is set in Italy, a country with which Germaine de Staël had become familiar during her wandering life in exile. The heroine lives in Rome, she has no parents or family; she has a personal fortune and is admired by all, from the highest circles to the general public, for her poetry. The male protagonist, the Scottish Lord Nelvil, first hears her referred to as: “the most celebrated woman in Italy. Corinne, poetess, writer, improvisatrice, and one of the greatest beauties of Rome.” Nelvil watches her crowning at the Capitol, a ceremony described with no economising on white horses, chariots designed in Antiquity, young female assistants clad in white, jubilant crowds of spectators, and the narrator’s detailed account of Corinne’s beauty. In his own country, Nelvil has seen statesmen honoured, “but this was the first time he had been a witness of the honours paid to a woman – a woman illustrious only by the gifts of genius. Her chariot of victory was not purchased at the cost of the tears of any human being, and no regret, no terror overshadowed that admiration which the highest endowments of nature, imagination, sentiment and mind, could not fail to excite.”

Corinne guides Nelvil around the historical monuments and art treasures of Italy, showing him the world of outer and inner beauty which she can bring to the marriage she would like with him. However, he abandons her for a young Englishwoman, a reserved and simple homely woman with none of Corinne’s genius. The theme of the novel is thus woman’s conflict between shining with her cerebral talents or with her housewifely abilities; “in the pursuit of fame it was always my endeavour to make myself beloved”, says Corinne, but her fame, on the contrary, ruins her chances with Nelvil. “But with us,” says an English acquaintance to Nelvil, “where men have active pursuits, women must be satisfied with the shade. That it would be a great pity to condemn Corinne to such a destiny, I freely acknowledge. I should be glad to see her upon the throne of England; but not beneath my humble roof.”

Domestic life in British homes, which Corinne compares to the leaden cloaks worn by the damned in Dante’s Inferno, is the very theme of Jane Austen’s six novels, written during the same period, but under very different circumstances and with a very different perspective on the home.

Jane Austen was a clergyman’s daughter and spent her entire life together with her mother and unmarried relatives in various English provincial towns. Life as an unmarried woman might not have taken her into the maelstrom of major events, but life within her large family, which included her seven siblings with their various wives and children, gave her plenty of opportunity to observe middle-class social life where the struggle to keep up called for talent, boldness, and the ability to hold one’s own with the better-off.

This family life takes the central role in her novels, representing the culmination of the typically English genre of “domestic realism”, which had already been aired in Oliver Goldsmith’s The Vicar of Wakefield (1766). Austen’s plots turn on the problems of one or more couples getting together, but this is not romantic fiction in the sense of a story propelled by erotic passion. For Austen, coming together as a couple is a complicated process of linking up the personal inclinations, social status, and moral norms of the man and the woman; her agenda is less one of the individual’s happiness than of the sensible organisation of the social group.

Money and social position are things women win, with greater or lesser grace and fairness, through their connections with men. And so Mansfield Park (1814) opens:

“About thirty years ago Miss Maria Ward, of Huntingdon, with only seven thousand pounds, had the good luck to captivate Sir Thomas Bertram, of Mansfield Park, in the county of Northampton, and to be thereby raised to the rank of a baronet’s lady, with all the comforts and consequences of an handsome house and large income.”

A new marriage is a revolution in the social circle: it elevates the one woman and marginalises the other. “The contrast between Mrs. Churchill’s importance in the world, and Jane Fairfax’s, struck her; one was every thing, theother nothing”, thinks Emma, in the novel of the same name from 1816, as she muses on “the difference of woman’s destiny”. Austen writes about women’s lives during the period leading up to their crucial contracts of marriage: the period spent complying with the given social parameters in the most talented manner.

Both Germaine de Staël and Jane Austen transferred features from their social settings to their texts; the former brought along the wide cultural-historical horizon from the salon, with references to art, travel, and politics; the latter brought management of a household, its many personal relationships and hierarchies, with references to meals, fashion, and daily fellowship. “Her [Jane Austen’s] business is not half so much with the human heart”, wrote Charlotte Brontë (1816-55) “as with the human eyes, mouth, hands, and feet […].” Both authors include, however, plenty of psychology, conversation, and a woman’s perspective.

Germaine de Staël became a celebrity, read and translated all over Europe; she was the central character in the series of lectures held at the University of Copenhagen in 1871 by means of which Georg Brandes launched the Modern Breakthrough in the Nordic region. The lectures were published as Emigrantlitteraturen (1872; Eng. tr. The Emigrant Literature), which is the first volume of Hovedstrømninger i det 19de Aarhundredes Litteratur (1872-90; Eng. tr. Main Currents in Nineteenth Century Literature, 6 vols.), . Austen’s novels were highly popular with her contemporary British readers, but hardly known outside of Britain; only one of her novels, Sense and Sensibility (1811), was translated into Danish in the nineteenth century, and Brandes does not mention her at all. Staël can be said to have been a direct influence on Scandinavian literature, whereas Austen was only an indirect influence in the sense that her books are exemplary accounts of the housewife culture that underpinned Nordic women’s Romanticism.

In his novel Improvisatoren (1835; The Improvisatore, or, Life in Italy), a Danish counterpart to Corinne, Hans Christian Andersen, like Germaine de Staël, worked with a continuous fusing together of female types, but in his novel it is, of course, the fascinations of a male formation that must form a synthesis: “In Maria, I found all Lara’s beauty […] and Flaminia’s entire sisterly spirit.”

The agenda for the female Romantic author was to unite these two currents in literature written by women and in the female consciousness of the period. Interestingly, Germaine de Staël drew up this agenda herself as the conclusion to her novel. When Corinne meets the Englishwoman who Lord Nelvil chose in preference to her, and who, it turns out, is her half-sister, she says to her: “be Corinne and Lucy in one”. How this union occurred is revealed in Thomasine Gyllembourg’s writings.

In En Hverdags-Historie (1828; An Everyday Story), which embodies Thomasine Gyllembourg’s aesthetic and societal agenda, there are two women characters who are not representatives of, respectively, the housewife and the bel-esprit, but, on the contrary, each in her way – a bad and a good, in Gyllembourg’s opinion – unites something from both types of woman. The one has assembled, in a superficial manner, a little of the salon woman’s ‘erudition’ with a little of the housewife’s diligence, so that she is neither the one nor the other. The other woman, however, can both attend to the smooth running of the household and also provide entertainment with music and conversation, because she understands to “marier sa voix au son de la lyre”, as we read – she can harmonise the inner with the outer. Her actions and her nature are fused into a coherent self-image: the Romantic female identity that Gyllembourg wanted to highlight in her writings. In Rousseau’s words, she has: “taste without deep study, talent without art, judgment without learning.”

Translated by Ken Schubert