Much of the literature written by women after World War I bespoke a reaction to a new trend in sexual morality. The new age, the new woman, and the new sexuality echoed throughout its pages. Women’s greater social mobility was matched by more freedom in the spheres of intellect and imagination. The most audacious pre-war rebels, who had been regarded as dissolute demi-mondaines and a privileged class of bohemians with the right to love as they choose, were now role models for the new woman. But the bold paradigm had been altered, simplified, and commercialised along the way.

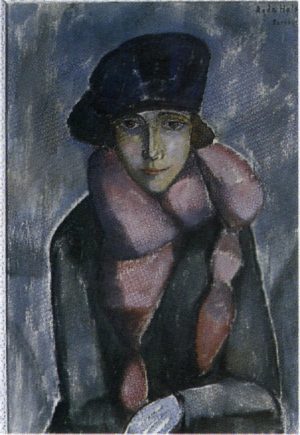

The new woman was a mass produced demi-mondaine, whose traits were most evident in the young medium of film. A discerning observer could glimpse the contours of a superficial creature of capitalism who lived in the city and earned her own – albeit small – income, which removed some of the constraints on her relationships with men. Make-up was her initiation rite to adulthood, and stylish apparel was her coat of arms. With her “sex appeal” and “professional” relationship to traditional femininity, she hovered around or simply crossed the line between the “good” and “bad” girl as defined by the old system of morality.

Det farliga könet (The Dangerous Sex), En kvinna i Paris (A Woman in Paris), Farlig kärlek (Dangerous Love), Förbjuden kärlek (Forbidden Love), Hennes syster från Paris (Her Sister from Paris), Annonsflickan (The Poster Girl), Hennes stora natt (Her Big Night), Räddad från vanära (Saved from Dishonour), Parisiska nätter (Parisian Nights), Hallåflickan (The Announcer), Åtrå (Lust), Lidelse (Desire), Gatans ängel (Street Angel), Syndens gata (Street of Sin), En kvinnas bekännelse (A Woman’s Confessions), Mannen, kvinnan och synden (Man, Woman, and Sin), En fallen ängel (A Fallen Angel), En kvinnas moral (A Woman’s Morality) are all titles of films screened at Stockholm theatres in the 1920s.

The new woman appears in the works of Elin Wägner (1882-1949) and Marika Stiernstedt (1875-1954) as well as those of less renowned authors like Py Sörman (1897-1947), Ingeborg Björklund (1897-1974), and Gertrud Almqvist (1875-1954). While these novels portray her as dangerous and shallow, she is enticing – even for her own sex – behind the frightening façade. The evil temptress is sometimes depicted as triumph and retribution personified. Her role is to avenge the abandoned and betrayed members of her sex. She is rarely the protagonist, but – unlike her counterpart in pre-war literature by women – she always escapes punishment. In the novels of the 1920s, the deceitful man is the one to be disposed of.

The “true” woman is a morally conscious being who stoically chooses her narrow path and duty, the bitter consequences of love. She is an incarnation of the teenage heroine, a kind of sexualised Polyanna. Her sexuality is the corporeal and spiritual fusion of love and affinity à la Ellen Key. The erotic Polyanna is the new heroine for these authors, the object of their daydreams, and the channel through which they invest women with dignity.

The title character of Eleanor H. Porter’s Polyanna, an enormously popular book for girls, is an eleven-year-old orphan who has learned since early childhood to see the bright side of life and who wins over everyone she meets with her smile and good humour. She is virtue incarnate; duty has become her second nature.

Caught between Two Worlds

Older women, who had experienced the downside of the old sexual order, also took their measure of the new age. Among them were Gertrud Almqvist, who started off in 1899 and wrote a number of books before the war, including Den svenska kvinnan (1910; The Swedish Woman). Her final work, which she published under the pseudonym of Molly Molander, was entitled I tolfte timmen: En gammal, dåraktig kvinnas bekännelser (1929; At the Twelfth Hour: Confessions of a Foolish Old Woman).The novel is written in the form of a diary by a certain Mrs Berglöf, who starts psychoanalysis in her middle age, only to be told that a woman’s true calling is subservience to men. Her confessions, which revolve around love and sexuality, are defined by the new framework of psychoanalysis as filtered through the worldview of a Swedish neurologist. Under the surface of facetiousness and irony, however, lurks a yearning for ecstatic love, more powerfully expressed than by younger authors. Also discernible is a sense of bitterness at having been caught between two worlds. Almqvist’s sullen heroine has lost out on the old system but is not young enough to benefit from the new one.

Han (1921; He), Py Sörman’s first novel, is about the confusion that arises when a young female artist who has everything to gain from the new system follows the dictates of the old one. Highly purposeful at the beginning, she gives her work and companionate love to a fellow painter on the boat, and jumps on the train from Paris to Stockholm when a daemonic violinist summons her. The novel ends with the words: “He is alone …! He longs for …”

As these books suggest, the new system of sexual morality was experiencing severe birth pangs. The new, more ‘emancipated’ feminine ideal was forged by the war, urbanisation, universal suffrage, expansion of the labour market, and the ascendancy of psychoanalysis. Ellen Key’s belief in the autonomy of deep, all-embracing love represented the link between the old and new systems, the alibi on which the writers of the 1920s relied. True love, according to Key, could never be immoral, whether within or outside of marriage. These books deal with the social complications that arise when this doctrine is adhered to.

But how about the new system of sexual morality? An official Swedish report in 1936 painted sexuality in broad strokes as a positive force analogous to electricity. Its technical, emotional, and biological mechanisms must be used properly in order to benefit both the individual and society. The ideal of marriage was more down-to-earth than before the war: it was to be based on companionate love and egalitarianism.

Ingeborg Björklund’s first novel, En kvinna på väg (1926; A Woman on the Way), presents the victims of the new system, employing a uniquely accusatory tone when describing men, who are betrayers by their very nature. The first part of the novel, dedicated to Wägner, graphically describes the home for unmarried mothers to which Isa Borg, the daughter of a pastor, is sent after being raped. The second part, dedicated to Arnold Ljungdal, Björklund’s Marxist husband, reintroduces Isa as an independent career woman who engages in casual love affairs. She meets Mr Right, a little too hastily perhaps, on the last page.

Björklund offers a graphic account of the way that Isa is forced to give birth in secret – details that Marika Stiernstedt had so discreetly omitted in Fröken Liwin (1925; Miss Liwin), the novel she had published the previous year on the same theme of an unwanted love child and an abandoned woman. Elma Liwin is a spinster and successful businesswoman, an affectionately drawn feminist stereotype. Smart and orderly, she wears heavy shoes and has firm, beguiling lips – even when holding a cigarette. Behind her irreproachable façade, however, lurks a deep, dark secret: a love affair with a musician who had seduced and then left her when she became pregnant. She writes to him trustingly, but receives the kind of cruel letter that literature by women so meticulously recites: “Was it his fault that she had thrown herself at him? Not only that, but he was younger than her and he wasn’t about to play her game. The child wasn’t his.” So she, too, has to bear the cross to the home for unwed mothers and give up her infant daughter the day she is born. At the age of forty, Elma’s painstakingly constructed world begins to collapse. The feeling of emptiness keeps her up at night, makes her irritable, and poisons her life. After a while, she realises that she longs for her daughter and tries to bond with her. The encounter with the new woman forces her to reach a decision. She will rescue her daughter from turning into an amoral woman who cunningly exploits her daemonic appeal to turn the tables on men: love them and leave them. The reunion with her steadfast daughter who “intends to manage her own freedom” is Elma’s death knell. Nevertheless, her daughter’s ability to understand Elma’s fate at the end of the book gives her the strength to turn away the man she is in love with when he tries to rape her.

The Problem of Women’s Freedom

With her French-Polish aristocratic roots and socialist sympathies, Stiernstedt may seem to be the odd woman out in Swedish literature. However, her prolific output reflects the temper of literature in Sweden in the first half of the twentieth century. She was a pacesetter in the 1920s not only with the provocative Fröken Liwin, but with Ullabella, which reinvigorated fiction for adolescent girls by meeting difficult existential issues head on. The story is told from the perspective of Ullabella, a contemplative only child who grows up with her insolvent inventor father and a strict but faithful maidservant.

Stiernstedt’s first twentieth-century novels examined infidelity and double standards in the spirit of Ellen Key.

Marika Stiernstedt began her correspondence with Lubbe Nordström, her second husband, by responding to his critique that “sensuality and instinct held sway at the expense of heart and feeling” in her novels:

“When you get to know me better, you might talk about the same fault in me. But why a fault? I know that ‘instinct’ has a good deal of power over me.” The ambivalence about his wife and the fear of sex that made their marriage a purgatory are already evident in the ominously ecstatic exclamation that appears in a 1922 letter: “I love! Not with the flesh but with the spirit. And Marika is the one I love.”

Relationships between women and men grew more complex in her later works. “The fundamental problem her writing confronts is that of women’s freedom”, John Landquist wrote in 1925. What he was referring to was the conflict between love as female destiny and the new woman’s desire to live a more independent life. This moral question pervades Stiernstedt’s writing and assumes various guises, as represented by an impressive gallery of both agreeable and disagreeable female characters.

She focuses increasingly on the strains and difficulties of fully expressing femininity in its modern form when there is no such thing as a modern man. She rejects Key’s idealistic doctrine of love, arguing that “it partly stemmed from an insufficient experience of all the trials and tribulations that ordinary existence confronts us with.” Man glömmer ingenting (1940; You Never Forget), a novel about such everyday ordeals within the context of a divorce, was also Sweden’s first literary portrait of a female alcoholic.

Stiernstedt, who voted for the Social Democrats and admired future Prime Minister Hjalmar Branting, was a staunch pacifist during World War I and grew more radical later in life. The novels she wrote in the 1940s are unflinchingly anti-Fascist. Her bestseller Attentat i Paris (1940; Assassination in Paris),which has been translated into many languages, argues that all thoughtful people must take a stand against Nazi barbarity. Indiansommar 39 (1944; Indian Summer 39) takes place in occupied Poland. Banketten (1947; The Banquet), which was made into a film in 1948, describes the impact on the Swedish middle class of the catastrophe on the Continent – as personified by Serbian communist and resistance fighter Halla, who is rescued from a concentration camp by the Bernadotte operation.

The “Happy Ending” of Novels of Emancipation

A number of first novels by female authors of the 1930s follow a modern woman on the perilous road to companionate marriage that would allow her to combine love and career. The curiosity that 1920s novels exhibited about the sexual provocatrice gave way to unequivocal support for hardworking women in a wool dress and tie, or blouse and slacks. A typical heroine was a child welfare officer, architect, teacher, or librarian. The new literature differed most emphatically from Stiernstedt’s fiction, its greatest influence, by virtue of its happy endings. The most prominent authors of novels of emancipation were Alice Lyttkens (1897-1991) and Dagmar Edqvist (1903-2000), and the one who found least favour in the eyes of the critics was Sigge Stark (1896-1964).

Den steniga vägen till lyckan (1924; The Rocky Path to Happiness) was the first book by Sigge Stark (the pseudonym of Signe Björnberg), who went on to write over a hundred highly popular novels. She was the twentieth century counterpart to the nineteenth century author Marie-Sophie Schwartz. Like her predecessor, she examined the issue of emancipation – in books like Manhatarklubben (1933; The Man Haters’ Club), which disbands at the end by virtue of a man’s kiss.

These novels often came up short from a literary point of view due to the idealisation required to reconcile a happy ending with the life of a modern career woman. Stiernstedt’s final work, Kring ett äktenskap (1953; About a Marriage), a no-holds-barred account of her infamous marriage to author Lubbe Nordström, served as a kind of literary terminus for the genre, which was soon popularised. The punctilious recital of the decline of an alcoholic and sexually ambivalent genius is unsparing in its directness. What good is freedom to the new woman if the new man turns out to be a cross between a hypocritical patriarch and a helpless child despite assurances of an egalitarian companionate marriage?

The novel can be interpreted as a belated reply to Ellen Key’s 1913 letter urging her to explore a motif worthy of her “storytelling abilities and the imperatives of justice: contemporary woman, who never has the time or luxury to love, who pushes her husband away and wakes up to an anguished ‘too late’”. Kring ett äktenskap shows just how naive Key, the “apostle of true femininity”, really was. Half a century of struggling for emancipation had made it clear to the “contemporary woman” that men were in no hurry to wake up.

Alice Lyttkens, who started off in 1932, found a wider readership with Det är icke sant (1935: It’s Not True), Det är mycket man måste (1936; There’s So Much You Have to Do), and Det är dit vi längtar (1937; That’s Where We Long to Be), a trilogy about young attorney Ann Ranmark and her struggle for emancipation. Kamrathustru, a psychologically convoluted first novel by Dagmar Edqvist, became an immediate bestseller and was adapted for the silver screen the same year. Edqvist lambasted the racism of her age in Fallet Ingegerd Bremssen (1937; The Case of Ingegerd Bremssen) with a psychoanalytical study of a rape victim. Edqvist eventually switched to historical novels – as did Lyttkens, whose big literary breakthrough came with Lyckans tempel (1943; Temple of Happiness), the first of several eighteenth century narratives about the women of the Tollman ship-owning dynasty and their longing for freedom.

Translated by Ken Schubert