How do you explain the odd sense of giddiness that you experience when encountering the poetry of Edith Södergran (1891-1923)? At first you think you are on solid ground, secure in a narrative of love where men are clueless about women’s souls: “Take the longing of my narrow shoulders” – thank you very much. Before long, however, you’ve been flung into the cosmos: “I walk on sun, I stand on sun, / I know nothing but the sun[…]”.

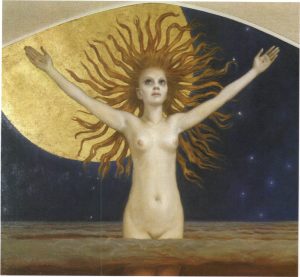

You meet the pale daughters of the sun and the forest; you become an Amazon and a virgin, a fairy princess, and a sister. You pay homage to Eros and the marble statue of Beauty; you hear the voice of autumn’s last flower – Orpheus, Diana, Ariadne, and Hamlet, the Hyacinth with its pink blossoms… Dionysus has a doppelgänger and her name is Snow White, and the Vierge moderne claims to be “a neuter”. Södergran’s writing cannot be pigeonholed – it thrives on its paradoxes, its solemn gravity, and its extravagant, occasionally playful authority. Far beyond the pleasure principle, it mocks the death instinct.

Although the basic vocabulary (love, happiness, beauty, longing, flowers, stars, sun, moon) of Södergran’s writing is a child of Romanticism, it is avant-garde in its radical use of language. Her metaphors are forever taking on new connotations; her words are perfidious. The meanings to which one poem gives rise may evaporate nonchalantly in the next. The inability of language to articulate the lesson of the new century – that God has died, taking with him man as woman’s master – is plain for all to see. Södergran offers a formula for an age of transition, in Nietzsche’s words.

Victoria Benedictsson anxiously wondered, “I am a woman; but I am an author; am I not therefore also partly a man?” in 1888, as the modern era was emerging. Twenty year later, a vierge moderne on the Karelian Isthmus made a supreme attempt to transcend the problem:

I am no woman. I am a neuter.

I am a child, a page and a bold resolve,

I am a laughing stripe of a scarlet sun…

I am a net for all greedy fish,

I am a toast to the glory of all women,

I am a step towards hazard and ruin,

I am a leap into freedom and self…

I am the whisper of blood in the ear of the man,

I am the soul’s ague, the longing and refusal of the flesh,

I am an entrance sign to new paradises.

I am a flame, searching and brazen,

I am water, deep but daring up to the knee,

I am fire and water in free and loyal union…

(“Vierge moderne”, Dikter).

In her collection of aphorisms Brokiga iakttagelser (1919; Motley Observations), Södergran writes that the “precious costume of truth that covers everything” is woven from the paltry “play of contrast”. Her writing forges this contrast through the frequent use of paradox, and not least of negation.

Negation is important in Södergran’s poems; they teem with words like nobody, nothing, and not, and the prefix “un” (unalterable, unavoidable, unnoticed, unceasing, unseen, unstained, etc.) is rampant.

The scarcity of negation in the apocalyptic poetry of her middle period is striking evidence that its role is to soften the hubris of her assertions. But its main effect is to inject the sense of insufficiency, guilt, and futility to which her writing ultimately leads. Initially negation represents men, who are denied three times in “Violetta skymningar” (Eng. tr. “Violet Twilights”), her first volume, consistent with the emancipated woman’s provocative paradigm: “The man has not arrived, has never been, will never be”, before the devout narrator, the daughter of the sun, unites with “the least expected and the deepest red”. Like the narrator in Dikter (1916; Eng. tr. Poems), those beautiful sisters, warriors, heroines, and horsewomen mistrust men, who with their empty eyes believe in “nothing”, whose children therefore do “not” live. But she does not direct her negation primarily at men; even in her early poetry, it is associated with death as well. In “Avsked” (Eng. tr. “Farewell”), the narrator takes leave of the sisters; negations swirl around her, she closes her eyes, and suddenly he stands there, a knight whose fatal caresses she has reluctantly begun to long for. But he has come too late for the virgin with dark rings under her eyes, who must slay her own dragon.

This poetry is ultimately about the power of self-definition, of “recreating oneself from the ashes”, as Södergran wrote to Elmer Diktonius the year before her death. “Makt” (Power), one of the last poems she published, demonstrates how well that strategy works. The poem chisels out a self whose force of attraction grows in step with the repeated negations. A strong, affirmative “I am” emerges from “nobody”, its equally strong antithesis.

I am the commanding strength. Where are those who will follow me?

Even the greatest bear their shields like dreamers.

Is there no one who can read the power of ecstasy in my eyes?

Is there no one who understands when in a low voice I say light words to those nearest?

I follow no law. I am a law unto myself

I am the person who takes.

In “Vierge moderne”, one of Södergran’s first poems, this polarisation foments a kind of revolution: “I am no woman”. The new subjectivity is nourished through the power of association with a series of tentative paradoxes, as if to elicit unsuspected truths. “I am a neuter. / I am a child, a page and a bold resolve.” Södergran experiments tirelessly with the transformational potential of poetic language. She carries polarisation to the outer limits of the probable, as in the feminist but absurd utopia of “Vierge moderne”: “I am fire and water in free and loyal union…” The image immediately annihilates itself.

Given the Freudian insight that denial reveals a desperate need to defend oneself, the extraordinary assertion “I am no woman” points to the repression of an underlying truth – perhaps the charged experience of singularity: ‘I am a woman. I am no neuter’. However, such a pronouncement would say nothing new, but quickly relegate women to their traditional role at the periphery of society. The statement “I am no woman,” on the other hand, transcends established cultural norms and transforms women into new beings who inhabit a doomed, war-torn patriarchy.

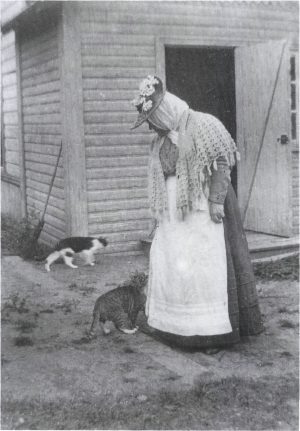

Fräulein Edith

The story of Södergran’s life is like a fin de siècle epilogue to early modernity’s novels of proud heroines, inconstant patriarchs. and rebellious daughters. Expelled from the embers of her childhood home into a world of war, revolution, and insurgency, she lived as a poet in exile, initially on whatever remnants of her grandfather’s fortune that her adventurer father had not succeeded in squandering before his death. But the one crucial respect in which her biography differed from the young heroines of late nineteenth century novels was fundamental to her writing: Södergran lived in creative symbiosis with her mother Helena, who became thoroughly absorbed in her daughter’s career and was “better versed in world literature than she was in the art of baking bread”. Hagar Olsson spoke of the “droll, playful language” they used with each other. Her description of the little household portrays Edith and Helena Södergran as fairy tale characters, “charming” in their old-fashioned apparel, “one like a young hawk with a bold silhouette and the other most like a beaming, rosy-cheeked mother troll”.

Södergran spoke Swedish, her native language, as if she had learned it from a book: “oddly stiff, with an audible accent,” as philosopher of art Hans Ruin put it. Olsson maintained that she was most proficient in German, and poet Gunnar Ekelöf commented astutely that her “archaically awkward and studied phraseology betrays a lack of contact with her native language and its organic development”. No, he writes appreciatively, you cannot call Södergran a Swede – there’s something particularly Nordic about her foreignness.

It is fascinating to note that her metre breaks down in the very poem from The Oilcloth Notebook whose theme is homelessness in lyrical invocation. “I do not know to whom to bring my songs”. Around the same time, Södergran resolved to write in Swedish – one of the two languages spoken in Finland, her native country. Her decision sprang partly from a desire to promote Finland’s liberation and independence from Russia.

The name Södergran can be traced to the Österbotten province of Finland where her father Matts grew up. She was born in Saint Petersburg in 1992 and attended Die deutsche Hauptschule zu Sankt-Petri, the best of its four German middle schools. Her education was solid as could be from both a literary and linguistic point of view. The school taught a good deal of literature in the original. The curriculum of Höhere Töchterschule, the girl’s division, included broad exposure to Goethe, Schiller, Baudelaire, Gogol, and other classical authors. The ambitious schoolgirl was forced to drop out at the age of sixteen after being diagnosed with tuberculosis, the disease that had killed her father. The family’s summer house in Raivola, Karelia, was her principal residence for the rest of her life, with the exception of five stays at the sanatorium in Nummela and two sojourns in Davos, a Swiss spa resort. Thomas Mann’s novel Der Zauberberg (1924; Eng. tr. The Magic Mountain) describes Davos’s stimulating intellectual milieu.

Södergran was twenty-four years old in 1916, when she published her first book of poetry. The financially independent young lady could waive payment to have Dikter published by Holger Schildts Förlag. The situation had changed completely when Septemberlyran (1918; The September Lyre) was about to be published two years later. Her outer world was shattered; the Bolshevik Revolution had wiped out her fortune, which had been invested in Ukrainian bonds. All that she and her mother had left was their dilapidated twelve-room house on the Karelian Isthmus, where they lived in what Olsson called a state of near-starvation.

Emaciated and coughing blood, thrown into Finland’s most cosmopolitan – if remote – cauldron of Russian, Baltic, German, Finnish, and Swedish culture, Södergran planned brazenly for the worldwide revolution that the poets would one day lead. Meanwhile, she found herself awash in the turn-of-the-century wave of aestheticizing Nietzscheanism. For her, however, it was a political project. She felt, as Olsson wrote, “her responsibility and role as an instrument of the spirit in the world”. Rudolf Steiner’s futuristic proposal of a tripartite society with independent delegations for political, economic, and spiritual life deeply appealed to her sensibility. By 1920 she was busy trying to form such a delegation, which she called “Övermänniskan” (The Übermensch), among the young representatives of Finland-Swedish modernism. She envisaged them meeting “high up among the chaste mountaintops,” and never “deign to exchange social niceties, upholster furniture, investigate the causes of world war, build temples, or direct plays.” No, she said, ordinary people are free to organise themselves; the spiritual capacity of the Superman more than suffices to renew the world – “we need only to stretch out our full hands”.

Rudolf Steiner (1861-1925) founded the Anthroposophical Society at Dornach, Switzerland in 1913. He was not simply a groundbreaking teacher. Following the chaos of World War I, his social ideas of resisting the omnipotence of the state by raising the status of spiritual and economic life were just what everybody had been waiting for. Many politicians, including future Swedish Prime Minister Hjalmar Branting, carried on a lively dialogue with him.

Feud over The September Lyre

Södergran spent her brief career as a poet in a state of relative disgrace. With an occasional exception, nobody but a small group of modernists – the objects of intense public scrutiny themselves – led by Olsson and Diktonius fought to uphold her professional honour. That was no easy task. The introduction to her second collection of poems, Septemberlyran, was interpreted as the product of a madly arrogant mind, and the critical debate often centred around the question of whether she was a raving lunatic or merely off her rocker.

“That my writing is poetry no one can deny, that it is verse I will not insist. I have attempted to bring certain refractory poems under one rhythm and have thereby discovered that I possess the power of the word and the image only under conditions of complete freedom, i.e. at the expense of the rhythm. My poems are to be taken as careless pencil sketches. As regards the content, I let my instinct build up what my intellect sees in expectation. My self-confidence depends on the fact that I have discovered my dimensions. It does not become me to make myself less than I am.”

“The feud over Septemberlyran” has gone down in history for its rancour. The controversy reached its peak when a docent in neurology was called in on the case and diagnosed the patient as exhibiting derangement in only some of her poems. Södergran did nothing to help herself when she published a letter to the editor entitled “Individual Art” and stating that Septemberlyran was “not intended for the public, not even for the higher intellectual circles, but only for those few individuals who stand nearest the frontier of the future.” It was the type of elitism that led Jumbo, a columnist for the Helsinki daily Hufvudstadsbladet, to accuse her and other modernists of spreading “the kind of spiritual contagion that is referred to as Bolshevism in its political form”.

Södergran couldn’t understand the reaction to the book. Certainly her first collection, Dikter, had been received with wariness, and the provincial press had bombarded her with scorn. Writing in Dagens Press, her fellow author Erik Grotenfeldt was kindest to the first book, calling it both remarkable and gratifying: “It introduces not only a new name, but an unprecedented direction, to our poetry.”

He was referring to Södergran’s continental background. The last thing you could call the book was Swedish – or Finnish. Her aesthetic idealism was rooted in the Germany of the 1890s and its Nietzschean influences (the circle around the journal Blätter fur die Kunst). As Gunnar Tideström, the first Södergran scholar, put it: “Defiant self-assertiveness and a cosmic sense of the self were almost a tradition” in both classical and contemporary European writing. To fully describe Södergran’s artistic influences you would have to add Russian futurism and French symbolism to German expressionism. However, she had only a passing acquaintance with the Swedish lyrical tradition of either Finland or Sweden. She saw herself as a cosmopolitan poet with a responsibility for succeeding generations. No wonder she was taken aback by accusations of spiritual Bolshevism and formlessness.

“Formless eruptions of a sick spirit’s woes,” wrote Arbetarbladet of Dikter, and Hufvudstadsbladet vented its dissatisfaction with the book’s “supreme contempt for any artistic demands”. The hostile reception to Södergran’s free verse by the provincial newspapers was due to the fact that the primary task of Finland-Swedish literature in the early 1900s was preservation of the language. Rescuing the native language of the Swedish-speaking minority would assure them of a place in independent Finland.

Södergran’s subsequent collections, Rosenaltaret (1919; The Rose Altar), and Framtidens skugga (1920; The Shadow of the Future), were received in much the same way. Meanwhile, her collection of aphorisms, Brokiga iakttagelser (1919; Motley Observations), was universally ignored. Södergran resolved to turn her back on Finland and stop “making poems”. She devoted her remaining years to translating the best poetry of contemporary young Finns to German, hoping to publish an anthology in Germany. “We’ve got to beat our own drum,” she wrote to Olsson in 1922. “I can sit and twiddle my thumbs in this one-horse town until doomsday.” The project came to naught, and Södergran died at the age of thirty-one on 24 June 1923.

Given the literary climate of Sweden, Södergran’s modernist poetry would likely have been excoriated there as well. At the annual meeting of the Swedish Academy in December 1919, Erik Axel Karlfeldt drew a parallel between a battered Europe and modern poetry, which he called “a lexicon of disintegration, morphological anarchy, and poetic Bolshevism.” He argued that language “is much too precious a tool to be smashed to pieces by undisciplined hands” and called for “poetry that can speak clearly, without an affected, primitive stutter.”

However, her poetry supplied the passion that adversity demanded; more courageously than anyone else either before or after her, she broadened and transformed the new vitality that lurked in the “shadow of the future.” She has provided several generations of female readers with a means of coming to grips with the mixed message of degradation and adoration that women receive in our society. But Södergran did not stop there. Her writing moulds a modern ‘self’ – as a woman.

I am a stranger in this land

that lies deep under the pressing sea,

the sun looks in with curling beams

and the air floats between my hands.

They told me that I was born in captivity –

here is no face that is known to me.

Am I a stone someone threw to the bottom?

Am I a fruit that was too heavy for its branch?

Here I lurk at the foot of the murmuring tree,

how will I get up the slippery stems?

Up there the tottering treetops meet,

there I will sit and spy out

the smoke from my homeland’s chimneys.

This is the only poem in her entire oeuvre entitled “I”. The poem is from the collection Dikter and typifies Södergran’s compulsive technique of catapulting herself from an experience of heaviness, often residing in the body and described in terms of humiliating obeisance to matter, towards the treetops, mountain peaks, or star-studded cosmos. Nietzsche’s Die Geburt der Tragödie (1872; Eng. tr. The Birth of Tragedy) speaks of a prophetic ‘self’ that lies “at the bottom of everything” and testifies to the human condition. Södergran presents the same kind of impersonal self, “through whose likenesses the gaze of the lyrical spirit penetrates this bottom of everything.” “Livet” (Eng. tr. “Life”) in Dikter portrays the self as its own captive and concludes mournfully: “Life is to despise oneself / and to lie motionless on the bottom of a well / and to know that the sun is shining up there[…]”. Such masochistically imbued images represent the self’s testimony to the limits that womanhood imposes on her. “Jag såg ett träd” (Eng. tr. “I Saw a Tree”), the first poem Södergran ever published, features a woman who throws dice with Death and loses, concluding with the line, “A circle was drawn around these things / that no one crosses over.” From the very beginning, she associated womanhood with incarceration, with closed circles and rings, as in “To Eros,” which was published posthumously, but presumably written early in her career.

[…] When girl children grow up

they are shut out from the light

and flung into a dark room.

Did my soul not float like a lucky star

before it was drawn into your red orbit?

See, I am bound, both hands and feet,

feel, I am forced in all my thoughts.

Eros, you cruellest of all gods,

I do not flee, I do not wait,

I only suffer like a beast.

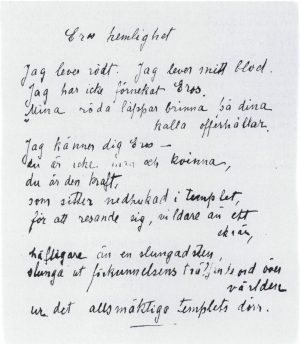

From “Till Eros” (Eng. tr. “To Eros”), Landet som icke är.

This perception of human beings as imprisoned in their flesh partly reflects the religious notion, found in Dostoevsky and others, that rapture and grace are attainable only through utter humiliation. In Södergran’s poetry, descent into matter is a condition of the spirit’s emancipatory ascent. Before the storm thrusts divine inspiration atop the holy mountain in “Fragment” (Eng. tr. “Fragment”) from Septemberlyran, the following unsavoury image of total abasement appears : “Children down there, loading dung unto the carts of the rabble, / on your knees! Do penance! Do not approach the holy thresholds yet[…]”. It is as though the beauty of the poems draws sustenance from bloody corpses, an aesthetic effect that is clearly on display in “Månens hemlighet” (Eng. tr. “The Moon’s Secret”) from Septemberlyran: “corpses shall lie among the alders on a wondrously beautiful beach”. Furious battles were fought around Raivola, which was on the railway line between Viborg and Saint Petersburg, during the Finnish Civil War. While Södergran was writing her collection of poems, the victorious White Guards were executing Red Guard prisoners of war. Starting off with images of fire and blood, Septemberlyran is a particularly impassioned and violent book. The world is drenched in blood, for “The spirit of the song is the war.”

The Oilcloth Notebook

The idea that an apocalypse was necessary and inevitable did not emerge for the first time in 1918. Hints appear even in Södergran’s adolescent poetry, reflections of the Russian religious and popular tradition that envisages a bloodbath as the price of resurrection. Living in Saint Petersburg eleven years before “Månens hemlighet” was published, the fifteen-year-old Södergran wrote her only extant poem in Russian, under the obvious influence of modernist Alexander Blok:

Quiet, calm, peaceful,

Secret powers

hide in the gloom.

Dark, rich

sticky, thick

blood flows.

Shadows slip,

shadows disappear.

There is no longer anything.

Desolate and dark.

In the cold dark

there is nothing.

In the dark earth

drunk with blood,

thick blood.

Life arises,

new life

from destruction.

A new future is made

In the black earth.

Contemporary author and critic Birgitta Trotzig has observed that Södergran framed a “comprehensive existential theme” for the first time in her Russian poem. And she did so “with imagery that is sufficiently complex to be simultaneous experienced on multiple levels that are neither mutually exclusive nor inimical to the simplicity of the original core image. It is a poem of protest, death, and love all wrapped up in a single image.” Södergran’s primary motifs are already in place – the longing for an earth-shaking world revolution and “Eros as a vital force or the allure of death”.

The poem is from the so-called Oilcloth Notebook, which contains 238 poems written between 1907 and 1909 – most of them in German. They leave little doubt that the schoolgirl was a passionate supporter of the struggle against the Tsarist autocracy. Black Sunday, on which the army shot at demonstrating workers on Nevsky Prospect (her route to school) and left the paving stones sticky with blood, took place two years before she wrote her Russian poem. The poem’s blood symbolism encompasses both the private experience of menstruation and the political certainty that violent but necessary social transformation is on the way. It is early evidence of Södergran’s synthetic ability to wrest the Übermensch from the ordinary woman.

The Oilcloth Notebook represents essentially all of Södergran’s literary remains. She methodically burned everything else to make sure that literary scholars (“the maggots”) would never get hold of it.

The first thing that strikes the reader of The Oilcloth Notebook is how much of what has condescendingly been referred to as “schoolgirl poetry” thematically foreshadows her mature writing.

The New Woman

“It can no longer be denied. The new woman is here. I am one myself, and I want to tell you about her”, says the protagonist of Elisabeth Dauthendey’s novel Das neue Weib und ihre Liebe (1901; Eng. tr. The New Woman and Her Love), which was widely read throughout Europe, including by Södergran. The new woman is portrayed as a Zarathustra in billowing skirts, waiting for the new man, who is conspicuous by his absence. “When will my time come?” Södergran’s first book of poetry appears to have emerged from the same raw experience.

“For the woman of today knows that she is condemned to loneliness, that she will never attain the perfect realisation of her entire being in unconstrained, reciprocal intimacy with a man,” Elisabeth Dauthendey wrote in her novel Das neue Weib und ihre Liebe, translated to Swedish in 1902 with a foreword by Ellen Key.As contemporary author and literary scholar Birgitta Holm has shown, many of Södergran’s early poems are of a piece with Dauthendey’s conclusions, which typified the feminist ideology of the age. What could illustrate that connection better than the famous final stanza of “Dagen svalnar…” (Eng. tr. “The Day Cools…”) from Dikter:

You searched for a flower and found a fruit. / You searched for a fountain and found a sea. / You searched for a woman and found a soul – you are disappointed.

För Södergran, the new woman finds her way through poetry, her source of gratification. Her contribution to a new world is to take leave of women’s marginal role and plant herself proudly on the world stage. In Septemberlyran, her second collection, alternately entitled The Glove of the Titan, Presumptuous Poems, Visions, the narrator vaults her way to the level of the gods, particularly in the score of poems dated September 1918. The protagonist speaks no longer from her heart, but from her breast – alternately anguished and brimming over with honey – or the evocations of her enormous lyre. Delivered from her imprisonment in the woman’s role that Dikter described, she proclaims from the heights: “You stand, hero with resurrected blood.”

In addition to the omnipresent sun, moon, and stars, her vocabulary revolves around triumph, strength, storm, pain, and Orpheus’ harp, which infuses life into the inert marble of art.

Drawing from Nietzsche, Södergran refashions her aesthetic into a historical and philosophical vision. Although it may seem precipitate to jump from the gender polarisation of Dikter to Nietzsche’s theory of the Apollonian and Dionysian principles, the correlation is there.

“Only as esthetic phenomena are existence and the universe forever justified.”

(Nietzsche, Die Geburt der Tragödie)

Nietzsche’s Die Geburt der Tragödie compares the two principles with the duality of gender and argues that art is just as dependent on their interplay as propagation of the species is on the existence of two sexes. The Apollonian, elastic, and epic ‘male’ principle is needed to tame the Dionysian ‘female’ principle of fantasy, naïveté, rapture, intoxication, and music. The ‘feminist’ perspective in Nietzsche’s writing is that the two principles are not superior or subordinate as the genders are in patriarchy, but coextensive, parallel. Now that Södergran can express the (female) human condition in Apollonian and Dionysian terms, the image of women in Dikter as the prey of men is transformed, abracadabra, into the image of women as hunters in Septemberlyran.

The exquisite marble body and “eternally pure” arms of Diana, goddess of the chase, are now worshipped limb by limb: “Oh what a heavenly consolation it is for our eyes / to behold you naked.” As in a medieval hymn to the Virgin Mary, the beholder’s glance glides downwards; the mouth and breast that “we gather dew to wash,” the knee, “magnificent and firm,” and the foot… However, Diana is no Madonna figure, no victim, but an executioner, like the autocratic Aurora, goddess of the dawn, described as a gale in “Die Zukunft” (The Future) from The Oilcloth Notebook, leading mortals into death so that a new, youthful race will arise in her image.

German literary scholar Inge Suchsland has shown that Södergran’s programmatic poem “Fragment” in Septemberlyran is based on a scene from Die Geburt der Tragödie in which the veiled Dionysus is enthroned between the mountaintops. Södergran, who herself “rose from death’s marble bed” so often, arbitrarily replaces Dionysus with the seemingly dead “maiden Snow White in her glass coffin.”. As in Nietzsche, however, where Dionysus’ exclamation of joy heralds an approach to the “innermost heart of things,” which is the “mother of being,” Snow White is a sign that points to the sublimating ability of art to transform and refine the palpability of the mother-child symbiosis. The first words of the poem are “life’s bacteria thrive on your slimy skin,”, transformed into “the honey of heaven,” an allusion to the Finnish national epic The Kalevala, in which the dead hero Lemminkäinen is healed by his mother using a heavenly honey bee. A battle rages between the mother of being – with her infected, slimy skin – and the heavenly father, who holds power over the Word. “God will create anew / He will reshape the world. / Into a clearer sign”, as Södergran writes in “Världen badar i blod” (Eng. tr. “The World Bathes in Blood”), one of the first poems in Septemberlyran.

Inge Suchsland’s “At elske og at kunne”. Weiblichkeit und symbolische Ordnung in der Lyrik von Edith Södergran (1922; “To Love and To Be Able”: Femininity and Symbolic Order in the Poetry of Edith Södergran) represented the first attempt to interpret Södergran’s writing from the perspective of feminist psychoanalysis.

Rosenaltaret retains beauty’s marble figure, while the imagery evokes bodily pain. The “flaring hammers” hew, and the heart is shattered to pieces. The preferred instrument of song is no longer the poet’s lyre, but the breast. The desperate plea of the imagery in “Besvärjelsen” (Eng. tr. “The Charm”) is excruciating: “I want to speak so that I open the whole of my breast before you / and so that my will grips you with hard tongs / like a pain, fear, sickness, love…”.

In Framtidens skugga, her next collection (and the last one published before her death) – particularly in the Eros poems – Södergran uses the entire body as a resonant instrument of the ultimate sensuality’s death wish. These poems, however, can only be understood in connection with the intense, charged relationship that arose between Södergran and Hagar Olsson, her “sister soul”.

Modernist sisters

“Fantastique”, the middle section of Rosenaltare, contains several poems written to Hagar Olsson, the young Finland-Swedish author and critic who was Södergran’s most important contact with contemporary cultural life during the last five years of her life. Olsson reviewed Septemberlyran in Dagens Press, and – with a few reservations – immediately regarded Södergran as one of the “truly gifted who have discarded the feeble old words and spoken in the language of a new time, a universal consciousness.” It wasn’t long before Södergran returned the favour and affirmed that Olsson was a “new type of individual” as well:

“Oh, it’d be such fun to come to you, I’d rush up the stairs. I have a sister and I’ve never heard her wonderful voice – I’m determined to see deep down inside you, you holiest person of all.” She wanted to know everything. In her second letter (January 1919), Södergran asked Olsson about her “level of education” and boasted of her own middle school training. After graduating from Fruntimmerskolan (girl’s school) in Viborg in 1910, Olsson fought with her father for permission to obtain an upper secondary degree as a privately tutored student, which Södergran was also preparing for at the same time.

Olsson wrote of having in childhood, like Södergran, waited for the liberation that the Bolshevik Revolution would bring, “devouring articles about the revolutionaries and terrorists, mostly upper class women who were inspired by Übermensch idealism. And how unbearable the oppressive feeling year after year that nothing was happening.”

The “magical enchantment” that arose between the two highly gifted women, both of whom regarded themselves as apostles of the future, left an indelible mark on twentieth century literary history. Their uncommon, fertile relationship played a significant role in the rapid emergence of modernism in Finland-Swedish, and soon in Nordic, literature.

Lying on her deathbed, Södergran wrote:

“Has she forgotten me Hagar aren’t we bound together in life and death. From [deep inside] me rises a spring of devotion, in my purest moment I call on you Lord offer up my heart’s blood in the loveliest limpid moments I remember Hagar.”

The friendship began in earnest when Olsson returned from her first visit to Raivola in February 1919 and sent Södergran her book Själarnas ansikten (1917; Soul Faces) The prose piece “Stjärnbarnet” (Starchild) struck Södergran as an uncanny prophecy of her own imminent death. The Starchild is a doomed and failed artist who initiates a visitor into the “mystery of horror”. The “far reaches of space” call to her, and one day she will find her way to that “which is not”.

“I came to the Starchild and my heart opened to her. She sat at my feet with her slender arms around my knee; her marvellously transparent and calm, luminous face was turned towards me, and I gazed at it with trepidation and holy acceptance, for it was only soul…

“‘You see,’ whispered the Starchild, and her eyes grew deeper as in secret dread, ‘You see that closed white door.’

“I followed her gaze and saw the door and, it’s true, during the next few years I never saw it other than closed.

“‘It is the room of my nights,’ continued the Starchild, ‘my loneliest room through whose windows I never saw anything but the procession of the fragile stars in the deep, holy night…’

“Even I sensed the swoosh of horror’s wings and I trembled in my heart of hearts, for I found myself face to face with that which is not.”

Södergran may have reacted with “horror” to his little passage (“spook literature”) because she felt that Olsson had peered into her innermost being. The final poems of The Oilcloth Notebook, which Olsson knew nothing about, contain the explanation. They describe a young woman as four inner rooms through which her beloved strolls. Love dwells in the first room, redolent with flowers. The second room is filled with destitution, weariness, and despair. The third room is cosmopolitan; the backdrop shifts from one minute to the next, and the mood oscillates from childishness to belligerence. The fourth room is actually two: an “antechamber to another, / There is a door, draped with white veils,” behind which someone is sitting. The antechamber symbolizes a passageway to the inner sanctum of womanhood where men do not dare, or want, to tread.

But the male protagonist of “The Starchild” enters the antechamber by force and finds the hideous madwoman. Södergran, who regarded her fatal illness as a moral defect and tried to hide her “abasement” from Olsson, saw her “sister’s” story as confirmation that her attempts to overcome her fear of death had been in vain. Offence is the best defence; she would defy her dread of the hereafter and its unreality, transcendence, by convincing Olsson that she herself was healthy and her friend was the sick one: “Hagar, you are a sick child. Come to my embrace as to a mother’s. I sense within me the power to defeat your enemy; let me dispose over you. Surrender yourself to my will, to the sun, to the life-force […]”, she wrote in February 1919. Not until almost a year later, in January 1920, could she acknowledge her denial. “Now I know why I loathed the Starchild so much… I am steeped in that dread myself and could have found myself in danger.” “Gudabarnet” (Eng. tr. “The Child of God”) in Rosenaltaret, a direct response to “The Starchild”, calls Olsson the “child of god”, and the narrator sings to her consolingly on her “gold lyre” of the wondrous future when their dreams will come true. “Child of heroes, child of luck! / We shall wait together / for the day of fairy-tales.”

“Two years ago I wrote a poem. Each stanza began ‘I want a playmate’ (of course I was thinking of a male one) and it ended ‘I want a playmate who can break forth from dead granite and defy eternity’. Now I have my happy playmate…”, Södergran wrote to Olsson on 26 January 1919.

After a hiatus of almost three months in their correspondence, Södergran’s inner struggle had clearly subsided. She claims to be wandering down the same road as the aged Goethe and urges Olsson to follow her. It may very well have been at this point, in her intensive dialogue with the “sick child”, that she wrote “Ingenting” (Eng. tr. “Nothing”), a lovely poem that was published after her death. Just as the tormented father in Goethe’s “Erlköning” (Eng. tr. “Erlking”) rides through the night with his dying child and repeats: “Be quiet, stay quiet, my child”, Södergran’s narrator talks to her child as if to comfort herself.

Be still, my child, nothing exists,

and all is as you see: forest, smoke, and the flight of the railway tracks.

Somewhere far away in a distant land

there is a bluer sky and a wall with roses

or a palm tree and a wamer wind –

and that is all.

There is nothing more than the snow on the spruce-fir’s bough.

There is nothing to kiss with warm lips,

and all lips cool with time.

But you say, my child, that your heart is powerful,

and that living in vain is inferior to dying.

What did you want of death?

Do you know the disgust his clothes spread?

And nothing is more revolting than death by one’s own hand.

We ought to love life’s long hours of sickness

and narrow years of longing

like the brief moments when the desert flowers.

(“Ingenting”, Landet som icke är)

“Landet som icke är” (Eng. tr. “The Land That Is Not”) also appears to be a product of the charged relationship, which literary historian Olof Enckell calls “counteraction” rather than “interaction,” between the two poets. In the spring of 1919, Södergran expressed a desire to jolt Olsson, suffering from melancholia induced by mystical inspiration, “out of that which is not” with “a powerful shock”. She began to qualify her point of view that same November: “… I have brought myself to a new kind of longing. I believe that I have done mysticism an injustice. However, I don’t want that which is not, but that which is”. A letter that she wrote the following May nevertheless contained three exclamations of horror and its mysteries reminiscent of the theme of “Landet som icke är”: “Oh how I long for the eternal homeland of mankind. Oh how I long for the eternal homeland of mankind. … I will find the eternal homeland of mankind.”

The upheaval in Södergran’s soul that followed “Ingenting” manifested in the rhetorical invocations of “Landet som icke är” , particularly the final lines. The human child who “is nothing but certainty” asks “Who is my beloved? What is his name?” The reply is an echo, a reprisal of the question in the form of a declaration. The lines are constructed as a chiasmus that intensifies the rhetorical nature of the poem, pointing to a symbiotic perception of love that eschews a clear boundary between the self and the other.

I long for the land that is not,

for I am weary of desiring all things that are.

The moon tells me in silver runes

about the land that is not.

The land where all our wishes are wondrously fulfilled,

the land where all our chains fall away,

the land where we cool our gashed foreheads

in the moon’s dew.

My life was a hot delusion,

but I have found one thing and one thing I have truly gained

the path to the land that is not.

In the land that is not

my beloved walks with sparkling crown.

Who is my beloved? The night is dark

and the stars tremble in answer.

Who is my beloved? What is his name?

The heavens arch higher and higher,

and a human child

drowns in endless mists

and knows no answer.

but a human child is nothing other than certainty,

and it stretches out its arms higher than all heavens.

And there comes an answer: I am the one you love and always shall love.

(“Landet som icke är”, Landet som icke är)

The one you love is the one who loves you –a mother, a Christ, or a sister?

The galvanizing negation of Södergran’s poetry expands to encompass an entire world, and the question posed by the child answers itself in the most fabulous manner, a reiteration of “I am a law unto myself” emptied of its content. “My home is a magic land” wrote fifteen-year-old Södergran in The Oilcloth Notebook. Consistent with her youthful faith in lyricism, the poem portrays the land as uninhabitable.

Mysteries of the Flesh

“Mystery, I recognise you, I, the anti-mystic, enemy of ghosts”, Edith Södergran writes in “Den starkes kropp” (The Strong One’s Body, Eng. tr. “The Strong Man’s Body”) from Framtidens skugga, clearly alluding to her ongoing dialogue with Olsson. She was heading into deep water. As it turned out, acknowledging the mystery, “that which is not,” was tantamount to dethroning the Übermensch and allowing the unconscious to invade the self.

Framtidens skugga explores the same opposition between Eros, the “flesh”, and the gruesome mysticism of death that the hero of Olsson’s first novel, Lars Thorman och döden (1916; Lars Thorman and Death), constructs for himself. Södergran’s intention was to refute his choice of purity at the expense of Eros, the only true path. Now that Södergran was giving herself over to the Dionysian principle, she addressed Olsson as a representative of the Apollonian principle: “If I can’t sing Dionysus, I’m the unhappiest being ever created. The letter I’ve written you was a sorcerer’s letter…”, she confessed in March 1919. She exploits her playmate as someone who can “wound” her with the dagger of inspiration. “Have all the time felt within me such an infernal electricity that it was almost too much to bear… Have written poems, but this is not yet a period of inspiration. What I need is for someone to plunge a dagger into my breast. And there is no one I respect who can receive my suffering. Wound me, Hagar! If I could create now, everything I have written hitherto would be rubbish. This alone would be me… Near Christmas I shall publish a book called Mysteries of the Flesh, it is the opposite of the mysteries of horror… It is Eros conducting worship in his own Temple. It is the same Eros who is the ‘Wille zur Macht’.”

Power resides no longer in words, but in the body, the fragile foundation of her lyrical structure.

My body is a mystery.

So long as this fragile thing lives

you shall feel its might.

I will save the world.

Therefore Eros’ blood hurries to my lips,

and Eros’ gold into my tired locks.

I need only look,

tired or downcast: the earth is mine.

When I lie wearily on my bed

I know: in this weary hand is the world’s destiny.

It is the power that quivers in my shoes,

it is the power that moves in the folds of my garments,

it is the power that stands before you –

there is no abyss for it.

(“Instinkt”, Framtidens skugga)

Eros was a codeword that served to ignite the intellect in both Sweden and Swedish-speaking Finland. It had little to do with sexual encounters – one might reasonably contend that it was the antithesis of the libido in the Freudian sense of the word. Although Södergran did not write ordinary love poetry, many of her interpreters have immediately associated her frequent use of the word Eros with the concept of eroticism. According to Den platoniska kärleken (1915; Eng. tr. Platonic Love), a book by Finland-Swedish philosopher Rolf Lagerborg that achieved cult status, Eros is the fruitful love and rapture that “triumphs over lower impulses, cultivates thirst for knowledge, and rewards the perseverance of labour”. Södergran’s letter to the editor in Dagens Press on 19 December 1918, before she met Olsson, is clearly in the spirit of Lagerborg, describing her calling on the “frontier of the future” as follows:

“I myself am sacrificing every atom of my strength for my great cause, I am living the life of a saint, I am immersing myself in the greatest that the human spirit has produced, I avoid all inferior influences.”

“The wedding of Eros” is not the desire “that consecrated two bodies to each other,” but the healing flash of inspiration that she needed to electrify her ravaged frame. Södergran is engaged here in a bold attempt to articulate a kind of corporeal bliss beyond death, the state of decomposition, as in “Sällhet” (Eng. tr. “Bliss”) from Framtidens skugga:

Soon I will stretch myself on my bed,

small spirits shall cover me with white veils

and they shall strew red roses on my bier.

I am dying – for I am too happy.

I will even clench my teeth in bliss around my shroud.

I will curl my feet with bliss inside my white shoes,

and when my heart stops voluptuousness will lull it to sleep.

Let my bier be taken to the market-place –

here lies the bliss of earth.

Comparing this poem with “Dionysus” from Rosenaltaret, where the god comes like a gale while “the weeping earth” waits like a praying woman, Södergran has come full circle and again approaches the victim’s posture in which she began, and which she tried to redefine in Dikter. But the detour was not in vain.

In her essay “The New Woman”, published in 1913 while she was in exile, Aleksandra Kollontaj wrote that women authors were beginning to use an entirely feminine idiom. “They help us, finally, to recognize ‘the woman,’ the woman of the type newly being formed.” An article she wrote for a Russian magazine in 1923 argued that it was time to leave the anarchistic sexuality of the revolutionary phase, which she called “Eros without wings”, behind for the more demanding “winged Eros,” which she described as “love as a delicate web of every type of spiritual and moral feeling”.

Impotent Words

When the Übermensch is deconstructed into the frailty of the human condition, uncanny things begin to happen. The transformational, intoxicating storm of the future, on which Södergran previously relied to vault the mountaintops and convert matter to art, has died down. It is raining in the new world, as if to hasten the process of decomposition.

“I can’t write poetry any more. The Dionysiac claims my whole soul, but I can’t sing it,” she wrote to Olsson in March 1919. Zeal and inspiration are described as urges and bodily processes, as a “hunger for knowledge. It’s as if flames shot out of me; I long for a storm, suffering, pregnancy.”

The storm has abated; the lightning and thunder is no longer the vengeful god’s epistle to the unworthy mass of humanity. Instead it has taken possession of the body: “… the thunderstorm is in my breast, it will fall like a meteor. / I am a god in whom tempests rage; / with voracious eyes I draw everyone into my soul.”

As the body becomes a sign of power and mystery alike, she begins to question the communicative power of language: “I find it almost impossible to write. I just get all tangled up in what I want to say. Words are impotent.” Her most important metaphors are changing and seem to turn on her. The stars advance like a hostile army “to destroy, devour, scorch, exercise their power”. The sun, which had “tenderly” kissed “the virtuous body of a woman” in Dikter a few years earlier, offers only perfidious kisses of death in Framtidens skugga. The last published poem in Framtidens skugga refers twice to words as “pernicious”. Only “one’s own, one’s own” can furnish strength. With these two words, she fell silent as a poet, although she still had almost three years left to live. According to her letters to Olsson, November 1920 found her entering a heart-rending inner conflict, compelling her to seek consolation in Christ, which she saw as synonymous with annihilation, for “[…] the New Testament kills everything, all thought, all culture”. She had discarded once and for all the protective cape of the Übermensch with its ability to transcend human suffering.

In Den unga Hagar Olsson (1949; The Young Hagar Olsson), Olof Enckell wrote that the defiant affirmation of sensuality in the early poems of Framtidens skugga were transformed into “the urge for extinction clothed in the sensation of pleasure. … The sun undergoes a metamorphosis from the symbol of life and health to that of ecstatic consummation and thereby annihilation”.

Södergran was deeply moved when a camp for refugees from Kronstadt was built in the Raivola district in the spring of 1921.

“4,500 people living in the most profound misery. I’m ashamed to eat, I’m ashamed to lie in bed… These refugees weigh on my conscience; they don’t leave me a minute of peace. All this anonymous wretchedness should be witnessed and described so that compassionate hearts can have pity on them.”

She sent an SOS to Anna Lenah Elgström, a Swedish author who was in touch with the Red Cross.

In March 1922, Olsson commissioned the young Elmer Diktonius to visit Raivola. The person he found there was drowning in guilt feelings. Should not “despicable” art be exterminated? Södergran wondered, raising an admonitory finger to Diktonius, the socialist poet: “Whoever wants to identify with the masses should forgo all spiritual, as well as moral, supremacy and choose spiritual poverty – that is heaven’s standard.”

After returning from Raivola, Diktonius reported on his impressions in a euphoric letter to Olsson:

“It positively radiates from her, don’t you know. Södergran. And I never saw anybody laugh like her. So much Übermensch and so little mensch. No body at all, but a wonderful mind.”

She wrote to Diktonius a year before her death:

“… I want this to pierce your heart with iron hooks: with my poetry I torture, I crucify; because of my poems they beat horses; every form of cruelty has been signed by me; it has been perpetrated in my camp”.

Her faith in the power of words was unshaken, but had taken the form of megalomaniacal guilt feelings:

“When we write a poem, we mightily assist the powers that induce people to burn and torture each other, poke each other’s eyes out, cold-heartedly behold starvation[…]”.

Södergran’s writing is an ongoing process that seeks to demonstrate the inability of language to mirror the experience of being composed of good and evil, femininity and masculinity, executioner and victim. The question of responsibility may have looked different at a time when words like “the earth shall rise on new foundations” were used to justify genocide than in the age of mass media and talking heads. Södergran was ashamed of being an accomplice in the dictatorship of language that, in her eyes, was emerging in the new Russia. She wrote to Olsson six months before her death:

“Once upon a time we were so young, so young, when we became acquainted four years ago. Everything glimmered before our eyes. An enormous feeling of sobriety has now descended. Nothing gleams, nothing shines for me.”

Overwhelmed by the threatening shadow of the future, she had nothing more to say.

Translated by Ken Schubert