Around the year 1800, Danish-German aristocratic circles in Denmark and the state of Schleswig-Holstein enjoyed a flourishing ‘salon culture’, but in only a few cases did the salons have a more far-reaching impact as the ‘cultural centres’ of their day.

Seen in a Scandinavian context, the most interesting salon was that of Charlotte Schimmelmann (1757-1816), a much-visited salon known throughout Europe. In the wintertime, the salon was held at the Schimmelmann mansion in Bredgade, Copenhagen, and in the summer at the country house called Sølyst (the pleasure of the sea) in northern Zealand. As wife of Ernst Schimmelmann, Denmark’s Minister of Finance and, for a period, also Privy Councillor under the Bernstorffs, Charlotte Schimmelmann presided over many official social functions. She always made sure there were scholars and artists in attendance, so that elements such as music making, readings, and dramatisations would be the highlight of the programme. Oehlenschläger and Baggesen laid the foundations for their writing careers at Sølyst, a forum in which they encountered an audience with a European outlook, and a place where they received financial support.

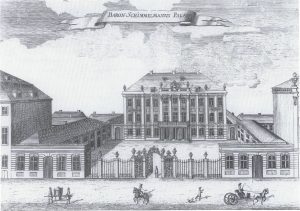

What became known as the Schimmelmann mansion was built by C. A. Berckentin in 1751; in 1761 it was bought by C. H. Schimmelmann, Ernst Schimmelmann’s father. The mansion was part of “Frederiksstaden”, the district surrounding Amalienborg Palace in Copenhagen, commissioned by and named after King Frederik V. The area was planned as an architectural manifestation of the new civic Copenhagen; however, with its mansions for persons of rank and money, it was more of a monument to the aristocratic backdrop of enlightened despotism. The district also housed the Bernstorff mansion and the Moltke mansion, which was taken over by Constantin Brun in 1796.

By gathering the royal court, nobility, diplomatic corps, and the higher official class in her salon, Charlotte Schimmelmann positioned herself at the heart of political events and as a focal point for the political players of her day. It is also apparent from her various correspondences – selections from which have been published in Efterladte Papirer fra den Reventlowske Familiekreds 1770–1827 (papers from the Reventlow family circle) edited by Louis Bobé – that she loved this role, and that now and then she exploited it – much to the annoyance of her contemporaries. She won her reputation as salon hostess, however, by being considered a ‘bel-esprit’, widely-read and well-informed about the latest European currents in scholarship, philosophy, and literature, and as the driving force behind her husband’s activities as patron of the arts. As salon hostess, she built bridges between central Europe and provincial Denmark, between high politics and intellectual life.

Charlotte Schimmelmann made her salon the brilliant manifestation of the aristocratic humanism that characterised the most far-sighted elements in the Danish-German aristocracy of rank and intellect, and which the Bernstorffs, the Reventlow brothers, and Ernst Schimmelmann translated into an early variety of aristocratic liberalism in a reform-inclined administration (agrarian reforms) behind the young crown prince (later King Frederik VI). With the intimate connection between Charlotte Schimmelmann’s cultural and Ernst Schimmelmann’s political activities, and between the salon’s aesthetic and political life, however, it inevitably followed the ups and downs of a government bent on reform and of Ernst Schimmelmann’s political career.

Initially, Charlotte and Ernst Schimmelmann had an exceptional sense of unity. Cosmopolitan in outlook and interested in Enlightenment ideas, they read the new philosophy together (Immanuel Kant, Johann Gottlieb Fichte, John Locke), the ‘literature of sensibility’ (Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock, Laurence Sterne, Edward Young), the German pre-Romantics (Johann Gottfried Herder, the young Schiller, the young Goethe) and, above all, Rousseau. They joined with the other young people in the circle around the Schimmelmann, Reventlow, Bernstorff, and Stolberg families in an attempt to convert the new spirit of the times into life as lived with their families and friends and in an appreciation of nature.

The fellowship of this noble, youthful set formed the soul of Charlotte Schimmelmann’s salon, but soon the participants became wrapped up in their own affairs: the Reventlow brothers, for example, in the running and development of their estates – Brahetrolleborg and Christianssæde – and in building up an education system for the now emancipated peasants; and Sybille and Sophie Reventlow in their steadily growing families. Charlotte and Ernst Schimmelmann, too, became more absorbed in their respective ‘duties’.

The salon was now structured in greater compliance with the social status of the participants, and had a broader base, but it was also more randomly composed. While official obligations and inflexible rules of propriety dominated social gatherings at the town mansion in winter, the summer gatherings at Sølyst took place in a more relaxed setting. However, even at Sølyst Charlotte Schimmelmann would often gather one hundred guests or more – people from all over Europe, and usually from other continents too – to a “grand petit diner” followed by a ball and entertainment of a ‘cultural’ variety. Before the midnight hour, Charlotte Schimmelmann would invite specially selected guests to take tea in her private apartment. It was at this point and in this innermost chamber that an actual literary salon was held, with readings from classical and modern as well as yet unpublished literature.

In the final decade of its existence, the Schimmelmann salon was but a faint reflection of its former self. Charlotte Schimmelmann became increasingly infirm, and even her women friends branded her eccentric. Perhaps she overstepped the acceptable norms of her time and her environment by insisting on the status of bel-esprit in her “Laterna Magica”, as she referred to her salon, rather than devoting herself to the role of wife to a husband increasingly dogged by adversity. Following Denmark’s unfortunate alliance with Napoleon, which Charlotte Schimmelmann too late and to no effect swayed her husband to oppose, and the failure of economic policy, which resulted in the national bankruptcy of 1813 and the loss of Norway in 1814, Ernst Schimmelmann and the aristocratic administration had definitively had their day. And thus, Charlotte Schimmelmann’s salon also lost its lifeblood. She had hoped to inject the salon with new life in the person of her foster daughter Louison, just like Friederike Brun had done at her contemporaneous Sophienholm salon in the person of her talented daughter Ida. Charlotte Schimmelmann’s foster daughter, however, neither could nor would take on this maternal legacy – time had run out on aristocratic salon life, and the salon had a quite different profile in the bourgeois milieus.

The other aristocratic salons were, in the main, German-orientated: Louise Stolberg (1746-1824) held a salon at Tremsbüttel, for example, and Julie Reventlow (1763-1816) at Emkendorf. Louise Stolberg was the ‘grand old lady’ of this faction; her letters were circulated as food for thought by way of introduction to the most recent developments in European philosophy and literature. Julie Reventlow, nicknamed “Passion Flower”, on the other hand, was particularly interested in the eighteenth-century literature of sensibility and its religious offshoots. She eventually became a decided opponent of religious rationalism, Enlightenment rationalism, and the reformist government in Copenhagen, while Louise Stolberg defended the French Revolution’s ideals of freedom and equality for longer, and more inveterately, than did the rest of her circle.

After the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen (1789) was made in Paris, Louise Stolberg wrote to her brother J. L. Reventlow in 1790: “The nobility of humankind, the true nobility, cannot be a monopoly, cannot be hereditary.”

Between Chronicle and Confession –

The Reventlow Letters

Charlotte Schimmelmann was a great letter-writer, corresponding primarily with friends and family in the leading political and cultural aristocratic milieu of the day; this correspondence has been published, in part, in Efterladte Papirer fra den Reventlowske Familiekreds 1770–1827 (papers from the Reventlow family circle). The letters give us a behind-the-scenes view of international and domestic political machinations as well as the social and daily life of the estates and mansions. We also gain an insight into what was read and discussed, and we get the impression that letters were a crucial agency of cultural exchange between geographically widely-dispersed correspondents and for the establishment of a shared cultural, European horizon in the spirit of aristocratic enlightened humanism. Louise Stolberg’s letters, in particular, had the status of intellectual gems bolstering up the sense of a shared cultural mission; the German poet Goethe said of them that herein was written a family and a world chronicle. This characterisation is based on an understanding that lineage and class are the vantage point from which the world is viewed, but that at the same time there was an open window both outwards – to the universal and historical – and inwards – to the interpreting subject. The aristocratic family letters are thus neither family documents nor literature and history, neither private nor public, intimate nor formal – they are indeed a mixed genre, a new departure.

The most regular exchange of letters was between women linked by a network of family and friendship ties, ‘sisters’ either by blood or by choice. Charlotte Schimmelmann, for example, had this kind of letter-writing relationship with Sybille Reventlow, her real sister, and Louise Stolberg, her ‘chosen’ sister. She came closest to the ‘natural’ letter style to which she aspired in letters written in her early days to Louise Stolberg. In these, she laid bare the emotional life of a young single woman on the threshold of marriage in an era and a social environment where the idea of wedlock based on love – and a concomitant new ideal of womanhood – was beginning to break through.

The only comprehensive account of the aristocratic salon and the exchange of letters between aristocratic women is found in Vilhelm Andersen’s four-volume Illustreret Dansk Litteraturhistorie (1929-34; Illustrated Danish Literary History). Like Louis Bobé, who wrote accounts of a number these noble families, Vilhelm Andersen also draws special attention to Charlotte Schimmelmann’s (adolescent) letters to her older friend Louise Stolberg with their “many vivid small particulars” from the milieu and political life.

We follow the engagement between Charlotte and Ernst Schimmelmann – in her letters, letters he wrote, and also letters written by members of their set. Charlotte was not seen as a particularly suitable match for Schimmelmann, and he felt called upon to defend their engagement by drawing attention to the ideal female traits and cerebral qualities of his chosen bride. Charlotte’s mother also stepped in with an animated letter-writing pen, stressing that the young couple harmoniously complemented one other as ideal reflections of their respective genders and in their shared literary interests. In the days leading up to their engagement, according to Charlotte’s mother, the couple exchanged Rousseau’s letters, which they then discussed in whispers as they sat on a corner sofa.

And Rousseau it was who developed the idea of the modern marriage of love, based on the complementary gender roles and shared interests of the mind. In Book V of his treatise on education, Émile (1762; Émile, or On Education), when writing about “Sophie, or Woman”, he defines womanhood through the duty to ‘please’ and the propensity for ‘coquetry’. In this he sees an ideal match for male desires, and one which must be protected and developed by means of moral and aesthetic instruction, teaching the girl to transform passion into inner reason and taste for correct conduct. Rousseau sees the woman’s alternative to the man’s ‘freedom’ as being ‘beauty’ of mind and body, through which she can achieve power not only over herself but also over the man.

Of the papers from the Reventlow family circle, Louis Bobé has included Louise Stolberg’s only literary attempt of her own: Emil: Ein Drama in drei Aufzügen (1782; Emil: A Drama in Three Acts). The drama is based on the fragment of a letter written by Rousseau, in which he outlines a sequel to his 1762 literary treatise on the nature of education, Émile (Émile, or On Education).

The letters written by Charlotte and Ernst Schimmelmann during their engagement chart the run-up to their marriage almost hour-by-hour in a game of feminine coquetry versus masculine courtliness, as when she writes to Louise Stolberg on 20 October 1781: “My heart had but a short journey to understand the language of his heart. O! How happy I am! – And yet I must tell you, – I must grant myself this satisfaction: – in Copenhagen I treated him with some reservation, a coolness, that almost caused his heart to break; I acted as though I understood him not. What moved me from the first instant, was not distrust of him, but of myself.”

A central theme in this and other letters is that she finds Schimmelmann immensely “interesting” because of his grief over his first, recently deceased wife Emilie. In her honour, he had a monument erected on a slope at Sølyst near the source of a stream – “Emiliekilden” (Emilie’s Spring) with its eternally weeping eye. After her death, Emilie, who in her lifetime had been an almost incorporeal, ethereal beauty, was revered as a symbol of the ideal female. And as such she was often held up to her young successor. This has been given perfect and yet ready-to-burst expression in a letter to Louise Stolberg written during the early days of Charlotte’s marriage.

Read with our modern mindset, the letter is a whole little sexual drama working its way, with increasing intensity, towards the climax. What lies in wait is, therefore, an anti-climax – the shadow of Emilie.

“I have again spent six happy days in Hellebæk with my friend; in unalloyed pleasure we have enjoyed the surroundings, and every day was marked by a new blessing. We abandoned ourselves entirely to nature and to ourselves; it seemed to me that this our delicious solitude should never come to an end. We had spent a whole day at Kullen, a day I shall never forget. The weather was as beautiful as could be and favoured our little journey. Sailing in the early morning was just as pleasant as fortunate, and in our humble, little boat we passed by a Russian fleet which had been lying at anchor off Hellebæk since the day before. The majestic vessels were unfurling their sails for departure, as if this spectacle too was made for us. We went ashore to a small Swedish village, one-and-a-half miles [seven statute miles, ed.] from Kullen. We boarded a carriage. Ernst and I held one another tightly by the arm so as not to be flung out. Ernst had kept me in ignorance about everything that awaited us on this delightful route, in order that I enjoy the surprise. We dined in a pretty little cabin close to the mountains. On our way to the cliffs, the lighthouse keeper was our only guide; he let us climb right to the top of them. Such magnificent nature! The sea was nearly perfectly calm; the waves lapped gently on the foot of the cliffs and formed a contrast to the mighty jags of the rock masses. We found Emilia’s name almost completely preserved, scratched into her rock; this wholly filled my soul and moved me more than I can express. E M and the final A are completely intact. On the homeward journey, the moon was our trusty guide across the sea, and we arrived back at Hellebæk past midnight, most contented with a lovely day.”

(Charlotte Schimmelmann in a letter to her friend Louise Stolberg, 1784.)

But what was the young wife feeling? When we try to understand the letter’s ‘confession’, expressions such as “my friend” and “language of the heart” are significant as indicators of a passion that is different to the one we would call ‘erotic’. The letter is also pre-modern in form, being a highly conscious stylistic experiment with the natural epistolary mode – without being, nonetheless, what we today understand by free or subjective.

The perception of love and marriage in the Reventlow collection of letters is closely bound up with the concept of friendship. Ernst Schimmelmann’s letters written in the 1770s to a friend from his youth, August Hennings – published as En Brevvexling fra Struensee–Tiden (A Correspondence from the Struensee Period) – bear witness to an early Romantic friendship, incanted in high-flown, ‘sentimental’ tones. This same timbre imbued the epistolary relationships in the Reventlow circle, particularly those between close relatives such as sisters and brothers – for example, between Julie Reventlow and Ernst Schimmelmann, and between Louise Stolberg and J. L. Reventlow. Between them, too, an ‘intense’ ‘meeting of minds’ prevailed, coming to expression in an epistolary style that gives the modern reader associations to the love letter.

In the later letters, the emotionally charged epistolary style has been toned down – or rather, the letters manifest an appreciable difference between a masculine and a feminine mode of expression. For men, it would seem to have been a culture of youth or courting – a case of equilibristic written exercises in the new sensibility and intensity – which faded out in proportion to increasing obligations to lineage, class, and State. For women, on the other hand, in line with increased distance to the husband and the dissolution of youth, a further shift in writing energy is perceptible, now to the intense epistolary friendships with female friends. It is clear, however, that aristocratic women also chose different routes. The provincial aristocrat with her large brood of children, Sophie Reventlow (1747-1822) identified with the form of beauty found in the new family idyll and motherhood utopia, as we can read in En dansk Statsmands Hjem omkring Aar 1800 (The Home of a Danish Statesman around 1800) and in Vore opblomstrende Børn (Our Flourishing Children). Sybille Reventlow (1753-1828) did the same, in that she also became involved with her husband’s idealistic campaign for the liberation of the peasants, and for school and educational reforms.

For their schools, the Reventlows drew inspiration from German educator Johann Basedow’s ideas on natural learning techniques and a relationship of trust between teacher and pupil; in the same spirit, both Sybille and Sophie Reventlow practiced a closer family life between husband and wife, and between parents and children, cf. Vore opblomstrende Børn.

Charlotte Schimmelmann, on the other hand – coquettish bel-esprit, and childless at the hub of events in her “Laterna Magica” – identified with a completely different sort of beauty; her letters were also sent beyond the family borders. For many years one of her other correspondents was Schiller’s wife, Charlotte Schiller; a selection from their epistolary friendship was published in Charlotte von Schiller und ihre Freunde (1860; Charlotte von Schiller and her Friends). The possibilities and limitations in Charlotte Schimmelmann’s choices are apparent from, on the one hand, her activities in the salon and as patron, and, on the other hand, her deepening nervous afflictions and isolation in her milieu – she was a woman who had overstepped the parameters of her environment.

Charlotte Schimmelmann was the driving force behind her husband’s official patronage activities – for example, in Fonden Ad Usus Publicos (the Foundation for the Benefit of the Public) and in Videnskabernes Selskab (the Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters) – just as she was the driving force behind his informal patronage of German and Danish writers, including Schiller, Baggesen, and Oehlenschläger.

Translated by Gaye Kynoch