In 1728, a catastrophic fire devastated large swathes of Copenhagen; one person who lost nearly everything was book printer and publisher Joachim Wielandt. In 1719 he had obtained the right to publish weekly and monthly newspapers in Danish, French, and German; his business had been successful because he had structured his publications in such a way that they addressed a range of social groupings in their preferred languages, while taking into account their particular news interests.

In 1724, Wielandt obtained an important charter: exclusive rights to dispatch his newspapers with the Danish royal mail, free of postage charge. He thus had a considerable advantage over other publishers. The privilege would later be of benefit to publisher Berling and his newspaper.

Wielandt’s German-language weekly paper covered foreign affairs, while his Danish-language monthly paper concentrated on domestic matters. The French-language monthly, mainly read by the aristocracy, covered political, cultural, and literary matters in an entertaining way.

The motto of Wielandt’s French newspaper was “pour servir le Publique”, and there were several types of public to serve in the Copenhagen of the day. Female readers would soon become a popular topic in the journal literature.

A learned readership could also find newsworthy material in Wielandt’s Nye Tidender om lærde Sager (News of Learned Matters), launched in 1720. In 1728, however, Wielandt’s printing house lay quite literally in ruins, and no sooner had he got his business more or less up and running again than he died, in 1730, leaving the fate of the printing establishment and the newspapers in the hands of his fifty-eight-year-old widow, Inger Windekilde. He was the third husband she had buried.

Inger Windekilde was a clergyman’s daughter from Stenløse, born in 1672. Her first husband was Jacob Graahe, a merchant, and her second husband was Thomas Hørning, member of the Board of Trade.

Having accumulated a considerable fortune from these marriages, she decided to make a stand and take on the competition from the other newspaper publishers. Inger Windekilde did very well, and in 1748 she sold her charters to printer and publisher Berling who, thanks to this transaction, was able to consolidate his position as newspaper publisher. Berling realised that local news was of interest to a Copenhagen readership, and in 1749 he remodelled one of Wielandt’s old Danish papers into Kiøbenhavnske Danske Post–Tidender (Copenhagen Danish Mail News), later to become today’s Berlingske Tidende. The newspaper, which came out twice a week, soon attracted many readers; it proved to be the start of a modern press dealing with current events, and targeting a general readership.

In the 1720s Wielandt had tried his hand at moral weekly magazines, and at periodicals based on German models, but there does not appear to have been a readership for moral periodicals until the 1740s.

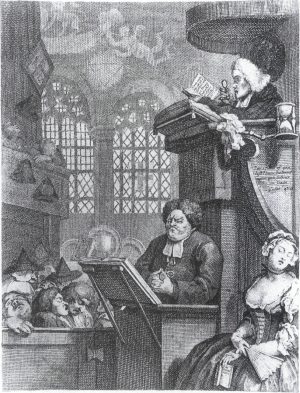

English periodical practice was introduced in 1742, with translations of Richard Steele’s and Joseph Addison’s The Spectator, launched in 1711; in Sweden, Olof von Dalin gave the English reasoning, moralising, and opinion-forming periodical its first Nordic counterpart with his Then Swänska Argus (The Swedish Argus). While newspapers in the 1700s stuck to printing ‘information’, the moral periodicals set forth and discussed opinions and attitudes to emotional, financial, and cultural subjects. Then Swänska Argus was translated into Danish during 1740 and 1741, and in 1744 the struggling theologian and law student Jørgen Riis began publishing Den danske Spectator samt Sande– og Granskningsmand (The Danish Spectator, Truth-Teller and Scientist). As ‘spectator’, and as ‘truth-teller’ (that is, judge or juror), Riis took culture and society in moral and satirical hand. Riis’ intention was to “assail vices under the banner of truth”, and he created satirical portraits of pedants and hypocrites, similar to those created by Holberg. Riis criticised the school system, the clergy, and adscription, and he found a particularly good subject on which to have an opinion with his satires of the ladies who, as far as he could see, flitted about the social life of Copenhagen when they should be attending to their duties in the kitchen. In the periodical literature of the eighteenth century, criticism of upbringing methods and criticism of pleasure-seeking and coquettish women, aristocrats and commoners alike, were tremendously popular topics. In this respect, the publishers were in no danger of offending the autocratic powers-that-be, and at the same time they could express thoughts on bourgeois virtues and ideals in the family and in society.

Riis’ English exemplar, The Spectator, often addressed the subject of the hypocrisy in girls’ upbringing, taking exception to marriage based on money, and favouring marriage as love alliance and mental connectedness; it advocated raising woman’s level of edification, particularly concerning her ‘natural’ assignments as housewife and child-rearer.

In The Spectator, Richard Steele advises the readers on matters of girls’ upbringing: “But sure there is a middle Way to be followed; the Management of a young Lady’s Person is not to be overlooked, but the Erudition of her Mind is much more to be regarded.”

In his Danish Spectator, Riis did not always settle for fine-tuning the bourgeois virtues; he pushed his satire into a direct attack on the female gender as such, leading an anonymous writer to cut him swiftly down to size. Riis was also criticised for the standard of philosophical argumentation, and he concluded his career in periodicals by publishing a two-pronged satire on both his Spectator and its opponents: Den danske Anti–Spectator eller En for Alle imod den danske Sande–Mand (The Danish Anti-Spectator, or One for All against the Danish Truth-Teller).

In “Letter to a Newly-Wed Lady” in No. 31 of Den danske Spectator, Riis implies that women are, and always will be, wayward:

“[…] every writer is wasting his efforts, or pouring water off a duck’s back, where he, by showing the woman her errors, endeavours to improve her. Madam puts the lie to the entire satirical world, which, with all its writings, can still not boast of a single woman that it has been able to put on the prudent track.”

The next issue carried a response from the newly-wed lady, possibly written by Frederik Christian Eilschov, in which we read: “Not a vice prevails in the one sex the equal of which cannot be found in the other; the only difference consists herein that men know better how to hide theirs than do women, and due to many reasons those are usually happier in their hypocrisy than these.”

Like the newspapers, the new periodical literature was published in several languages. The first-wave of “Spectator” literature was followed by the German-language Der Fremde (1745-46) and the French-language La Spectatrice Danoise (1748-50).

Der Fremde was published by the private secretary to the Saxon Minister in Copenhagen and later professor at the noblemen’s school (Ritterakademie) at Sorø, Johann Elias Schlegel. The periodical mapped bourgeois Copenhagen life in serials and essays, reported on public entertainments, printed short stories and fictitious letters, discussed the relationship between learning and culture, and profiled a gallery of Danish gentlemen and ladies. Schlegel was interested in Nordic mythology, and invented his own Nordic myths for his periodical.

In 1761, Professor Sneedorff from Sorø Academy launched his periodical Den patriotiske Tilskuer (The Patriotic Spectator), purportedly containing discussion papers from four male members of a patriotic society. Issues addressed were primarily those about which the male citizen should be enlightened and edified. A woman wrote, complaining about the lack of women in the society, and thereafter female virtue and edification were included in the debates; with a certain degree of irony, the ‘spectator’ then claimed that he was also the secretary of a women’s society.

Frenchman Laurant Angliviel de La Beaumelle came to Denmark as a private tutor, and towards the end of his stay he served by royal appointment as professor of French language and literature. His periodical La Spectatrice Danoise was published twice a week for two years. With a portion of self-irony and detachment, de La Beaumelle took it upon himself to “write like a woman”, and to his mind this involved a freely associative and descriptive style, in which the impulsive thought was the most important element. The periodical published theatre reviews, cultural critique, and social satire. La Spectatrice Danoise also printed an entertaining serial story: the diary kept by a young man from the landed gentry on a visit to Copenhagen. De La Beaumelle’s periodical was addressed to a female readership, and in the 1760s this readership was provided with a Danish periodical along with female writer characters: Fruentimmer–Tidenden og Fredags–Selskabet i Kiøbenhavn (1767-68; The Women’s News and Friday Society in Copenhagen). The merchant Hans Holck’s so-called ‘address office’ – Kiøbenhavns kgl. privilegerede Adresse–Contoir – was responsible for the publication. In 1759, Hans Holck had been awarded the royal charter to run the ‘address office’, compiling a directory of names and addresses to facilitate contact between private retailers and purchasers. He soon began publishing a paper with advertisements, Kiøbenhavns Adresse–Contoirs Efterretninger (Copenhagen Address Office News), swiftly followed by publication of directories, handbooks, periodicals, and notebooks. Hans Holck had acquired a taste for the publishing business, and this led him to launch a considerable number of new ventures, one being Fruentimmer–Tidenden og Fredags–Selskabet i Kiøbenhavn, in which an extensive gallery of female characters were given written voice. Like most periodicals at the time, Fruentimmer–Tidenden og Fredags–Selskabet i Kiøbenhavn was a weekly; it had but a brief life span, but it was quickly followed by Fruentimmer– og Mand–Folke–Tidenden (1768-70; Newspaper for Women and Men).

“The professor’s wife said: Let the paper be called just The Women’s News. It will surely win favour when it is of use and diversion for many, and not of harm and offence to some.” (No. 1, 1767)

The tradition was followed up some years later with Nye Fruentimmer– og Mand–Folke–Tidenden (1794-95; New Newspaper for Women and Men), which only reached a total of six issues.

Like many of the “Spectator” periodicals, Fruentimmer–Tidenden og Fredags–Selskabet i Kiøbenhavn was constructed around contributions from fictitious members of a society devoted to discussion and reasoning: in this case, “Fruentimmer-Tidenden” (The Women’s News), a cultured, bourgeois assembly of women, and the men’s “Fredags-Selskab” (Friday Society), composed of, among others, “a baker from the capital”, “a seafarer”, and “a citizen of the small market towns”. The female forum in the periodical included a “clergyman’s widow”, who described the tribulations of widowhood, a “professor’s wife”, who had her say about upbringing of children and marriage, a “barber’s widow”, who gave her opinions on various preparations, a “housekeeper”, who gave domestic advice, a “spinster”, who blamed the modern times and praised the old days – sometimes vice versa – and a “young actress of the stage”, who took care of innocent jest. In the “Spectator” periodicals, one and the same writer had often drawn up the contributions from various members of the society, and perhaps this was also the case in Fruentimmer–Tidenden og Fredags–Selskabet i Kiøbenhavn. None of the many contributors were named, and the contributions from women might not even have been written by women at all. What the periodical does primarily highlight, however, is that intelligent, well-read, and cultured women were in vogue. They quite simply made good copy, and discussion of women’s upbringing, virtue, and facility for learning was a popular pursuit in the various “Spectator” periodicals. In the first issue of Fruentimmer–Tidenden og Fredags–Selskabet i Kiøbenhavn, the female forum proclaimed:

“At this time we not only believe that women should read; but we believe even that they with advantage and good taste could write. We have living proof here among us. Thus there is good cause to eradicate those prejudices that have prevailed for long enough and have pursued a wrongful dominion against the one half of the human sex.

“Women’s genius is vigorous; their feelings are select, and their mental power is sharp; when these qualities are sustained by reading, reflection, and knowledge, then there is reason to promise oneself great profit from them.”

The “merry little maiden” complains about men in love comparing their beloved ones to Roman goddesses:

“[…] I for my part am not in the least anxious to be compared with a loose harlot such as Venus, I know her character far too well to believe I would have any honour in being placed in comparison with her. You men would not ever wish yourselves a Venus for a wife without fear of a Mars and making yourselves brothers in arms with Vulcan […] how would you like it if you received a letter from your sweetheart with such exaggerated expressions: my Archangel, my Vulcan, my Actaeon, my Idol and so on. You would have to judge us out of our minds.” (No. 18, 1767)

The Women’s Society addressed all manner of topics and issues concerning women’s everyday lives: from nursing and swaddling the infant child, clothes and beauty tips, and social etiquette to marital matters and general issues of propriety.

Readers of the periodicals received, for example, good advice about the care of their gardens, instruction as to “what there is to be done in a flower garden in the month of July”, and information on “some liqueurs that are suited to the removal of stains from garments and sundries,” and they made the acquaintance of an incomparable beauty product from Hamburg –

“It is made neither of mineral nor any other in the least acrid ingredients, but of the choice fat of young animals […]” – and were presented with a list of children in Copenhagen who had undergone the rite of confirmation. Many of the literary vignettes, witticisms, and contributions to discussion dealt with engagement, marriage, and family life. The “professor’s wife” clarified the periodical’s outlook on marriage: primarily, marriage should be seen as “an indissolvable friendship, a contract entered into together by man and woman from love” (No. 2, 1767). In Fruentimmer– og Mand–Folke–Tidenden, No. 13, 1770, the argument returns and we read an emphatic declaration that: “True genuine love is always based on high esteem.” The periodical’s stage-management of female opinion endeavoured to provide instruction in emotions and the cultivation of love. The ideal love should build on friendship between man and woman. The old seventeenth-century culture of préciosité lurks in the background of the periodical’s argumentation concerning love. In the eighteenth-century Danish periodicals, however, the radicalism of préciosité and aristocracy has been thoroughly rewritten into good and solid bourgeois virtue: while the French précieuses rejected marriage and motherhood, the Danish womenfolk took marriage to be the logical basis for their discussion of love.

Two, who one another’s equal be,

Two, who have no intention to deceive,

Two, who wish each other well,

Two, who are each other’s soul,

Two, who walk the straight and narrow path.

Two, who hold virtue in their hands,

Two, who love with all their hearts,

possess a paradise on earth.

Thus reads a short (in the Danish, rhyming) love poem from “Den lille muntre Jomfrue” (the merry little maiden) in Fruentimmer–Tidenden og Fredags–Selskabet i Kiøbenhavn, No. 15, 1767.

In the 1780s and 1790s, the women’s periodicals in Denmark were succeeded by moral light literature, often targeted at a female readership. Examples include Nyttig Underholdning for Læsere af begge Kiøn (1785; Beneficial Entertainment for Readers of Both Sexes), Amalies nyttige Moerskabstimer – Til de danske Damers Tieneste, (1794; Amalie’s Beneficial Hours of Amusement – In Service of the Danish Ladies), Flora. Et Maanedsskrift for det smukke Kiøn, (1795; Flora. A Monthly Publication for the Fair Sex), and many Nytaarsgaver (New Year’s Gifts). The number of periodicals and publications in general would suggest that by the end of the eighteenth century, a bourgeois female readership was on the rise. The unrestricted freedom of the press introduced by Johann Friedrich Struensee in 1770 led to a brief and hectic period for writers and readers. Pamphlets and other publications flowed off the Copenhagen presses, and even though this lack of restriction was soon tightened up again, this period was nonetheless characterised by a hitherto unseen level of writing and reading activity. Women writers, too, made their mark on the literary public in ‘magazines’ and ‘digests’ at the end of the 1700s.

The author Thomasine Gyllembourg, who in the 1800s created a new style of everyday prose dealing with the family life of the bourgeoisie, had grown up with the popular light novel of the 1780s. In connection with their divorce in 1801, her first husband, dramatist P.A. Heiberg, complained about the reading matter of her youth: “God forgive your departed aunt in her grave, she who afforded you, with novels and ill-chosen novels, a different notion of love than that which you should have.” Heiberg was referring in particular to sentimental literature that imitated Goethe’s Werther and Miller’s Siegwart.

These so-called ‘magazines’ and ‘digests’ were booklets containing Danish or translated stories and novels. One of the most important was the clergyman Hans Jørgen Birch’s Det nyeste Magazin af Fortællinger eller Samling af moralske, rørende og moersomme Romaner og Historier (1778-81; The Newest Magazine of Tales or Collection of Moral, Touching and Amusing Novels and Stories), twelve volumes in all. Birch and his successors introduced, often in their own translation, the sentimental bourgeois literature of the era. Birch had earlier, in 1775, translated Laurence Sterne’s A Sentimental Journey through France and Italy (Danish title Den følsomme Rejse gennem Italien og Frankrig), and in 1778, the German writer Johan Martin Miller’s Siegwart, eine Klostergeschichte (Siegwart, a Monastic Tale; Danish title Siegwart. En Klosterhistorie), and in his magazine he published, for example, translations of Frenchman Jean-François Marmontel’s Contes moraux (1755-59; Moral Tales) and of Henry Fielding’s great novel The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling (1749). The ‘digest’ publications continued in the 1780s with, for example, Bibliothek for det smukke Kön, udgivet af et Selskab (1784-90; Digest for the Fair Sex, published by a Society), which included contributions from Charlotte Baden and a number of anonymous female writers.

Both Charlotta Dorothea Biehl and Charlotte Baden were among the women depicted in Birch’s Billedgallerie for Fruentimmer, indeholdende Levnetsbeskrivelser over berømte og lærde danske, norske og udenlandske Fruentimmer (1793; Picture Gallery for Women, containing the Life Stories of Famous and Learned Danish, Norwegian and Foreign Women). The seventeenth- and eighteenth-century views of women who read and wrote came together in Birch’s Billedgallerie.

“I shall therefore urgently counsel all young women not to get married before their 18th year, they have yet a long path to traverse. The troubles of matrimony and the housewife will come soon enough. It is good for them to gather understanding and strength with which to endure them,” warns Birch in his Billedgallerie.

The interest of the scholarly milieu for collecting, registering, and comparing objects and strange phenomena – such as rare animal skeletons and learned ladies – was shared by Birch, and he wanted to “present striking examples of intelligent and virtuous women”. At the same time, however, Birch was engaged in the debate on the upbringing of girls, the virtues of the female sex and the institution of marriage, as covered by the periodicals and digests of the 1700s. He warned women against futile piano lessons and against playing actress in the “new-fangled drama societies”, but he could wholeheartedly recommend reading Richardson’s novels. In long moral expositions, Birch emphasised that women should be “chaste and virtuous ladies”, “loving and conscientious wives”, “paragons of virtue”, and “noble female citizens of the state”.

Should a woman have acquired far too much “understanding” from a sensible upbringing and virtuous reading material, Birch offers the following guidance: “If the wife has more understanding than the husband, she ought to be so clever as to hide her husband’s weakness as far as possible from the world, and treat him with all possible respect. This preserves her husband’s and her own honour, and makes her twice as respected by all right-minded people.”

Translated by Gaye Kynoch