Folktales are so many different things. Take the following tale, an abridged retelling of a variant on the story about “Mage” (Suchathing).

The tales are told in free adaptation from Oddbjørg Høgset: Erotiske folkeeventyr (1977; Erotic Folktales).

Quite a number of observations were noted down about interesting female informants, some of whom came across as strong personalities. In Utsyn over norsk folkedikting (1972; Survey of Norwegian Folk Literature), for example, Olav Bø mentions “the well-known Anne Golid [1773-1863], who told so much and so well for Landstad’s generation of collectors.”

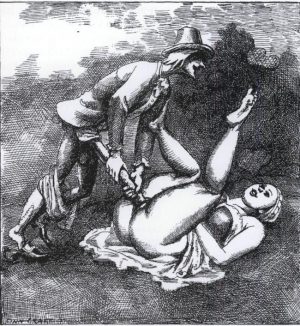

A man had to travel away from home while his wife was expecting. The local clergyman took advantage of his absence. He went to the wife and said: “O, God help you! Your husband has forgotten to make a nose on the child.” The wife, of course, wanted the child to have all its parts, “and so the clergyman made a nose on the child” in return for everything that had been prepared for the birth celebration. Upon his return home, the husband learnt of this transaction. He waited until the clergyman was out travelling himself, and then he visited the vicarage. When asked who he was, first by the kitchen girl and then by the clergyman’s wife, he replied: “cunt gilder”. The two women would, of course, like to be gilded, for which he demanded payment. “Well, then you must lie down, wide open, on the floor,” he said.

And so he laid eighteen eggs between the legs of the girl, the nineteenth he thrust in the hole. She asked his name and he replied that he was called Suchathing. He then asked her to remain lying motionless on the floor and wait until he came back. The same process was applied to the clergyman’s wife. She, too, had to pay for the gilding; the head of the clergyman’s foal was placed between her legs, she asked the man what he was called and at the end had to promise to wait. Suchathing then went home and relieved himself – of both varieties – into a leather bag. After that he met the clergyman, who wanted to know what he had in the bag: “Ah, I put that over my head when I’m sad,” said the man, “then I become happy again.” The clergyman persuaded him to sell him the bag. The clergyman went home. “Have you seen Suchathing,” asked the women in turn, as they lay on the floor, legs apart. “No, I’ve never seen such a thing, and God allow I never see it!” was the reply. And in his sadness about what had occurred, the clergyman pulled the leather bag over his head, “so the runny shit ran down all over him. And if he hasn’t washed, then he walks around covered in shit every single day.”

Or the tale about “Den seje pølse” (The Tough Sausage). A father is so anxious about his daughter’s virtue that he makes her lie next to the wall in his own bed every night. But the girl has a sweetheart, and she sneaks out on the pretext of an important errand. The two young people meet, and he takes her against a barn wall. It shakes so much that a scythe hanging on the wall falls down between them and chops off the lad’s willy. And “that was the end of that”. The girl goes back indoors and crawls over her father in the bed. As she does so, the severed item falls out. Her father asks what it is. “Well, it’s a piece of sausage I took for myself,” said the girl. The father bit into it. “That’s one jolly tough sausage, that is,” he said.

Have we ever heard or read such a thing? Not in the usual collections of folktales, that is for certain. They would seem to have been clinically purged of such elements – indecent situations and crude language. Some readers will perhaps nonetheless give a wry smile of recognition. The tales do indeed remind us of children’s puns and stories of our own day. Many of the young people’s ‘smutty stories’ are variations on the erotic folktale, albeit in versions that do not spell everything out in detail. The content of erotic skjemteeventyr (humorous stories) as well as that of children’s jokes is particularly concerned with the direct and unrefined reference to sexual relations and genitalia. Both men and women are thoroughly exposed. In addition, frequent use is made of a play on words in which innocuous terms, such as “mage”, take on double meanings: specification of identity by means of the anonymising pseudonym “Mage” is linked to the sexual act “mage” (mate)!

The technique involves a balance between knowledge and ignorance of the physical particulars of adult life. Sexual intercourse is forbidden. If it is called something else (“gilding”), however, then it is (almost) permitted. In some versions “Suchathing” even shaves the women’s hair off. Stupid and ridiculous – with the upshot being many types of loss and punishment – but in a way nonetheless ‘innocent’. Punishment and laughter are dealt out in equal portions to men and women alike.

The hero is the man with the clever repartee, able to trick people by means of his shrewd and quick-witted words. The play on words with his name follows a very old pattern. It recalls, inter alios, Homer’s hero Odysseus who exercises great cunning in his encounter with the one-eyed Cyclops Polyphemus. Odysseus manages to save himself by saying his name is “Oytis” (“Noman”). When the Cyclops’ sympathisers ask the name of the one who has perpetrated the atrocity, so that they know who to search for, the reply is “no man”. Indeed, that is that!

Children, however, know the material and technique of their jokes and tales without needing to read earlier and more eleborate sources in general editions of folktales. The hidden erotic tradition still thrives in the oral tradition – partly because it concerns something fundamentally human, and possibly partly as a consequence of being officially suppressed. No written tradition or public practice has taken on the function of the erotic tradition – except, perhaps, the ‘soft’ pornography of our own day, but this is devoid of humour. There has, however, been a degree of shift within the user-groups.

Systematic collection of material in Norway shows that girls and boys have an equal share in this kind of verbal daring. There is no great difference between the sexes when it comes to the tradition and passing on of these stories and jokes. Gigglingly bold, children put words to the adults’ many taboos. They gain a little information about sex, and they get to test out and lay down a number of established boundaries. Today, it is generally agreed that the erotic tradition is an important element in the process of children’s socialisation.

This was probably also the case in the nineteenth century. In earlier times, however, the folktales known as “Narrationes Lubricae”, salacious stories, were narrated by adult informants in the rural areas of Norway, in the villages. The children’s tradition was not a priority at the time. Awareness of the importance of childhood and its forms of expression is a modern phenomenon.

There are many women registered among the adult informants. The crude stories were/are by no means the sole reserve of male company. We know the names of approximately two-thirds of those who narrated the comic erotic material, and of these exactly one half are women. This is perhaps surprising. Many consider the folktale and, one would have thought, the cruder type in particular, to be more of a male-centric form. We connect female informants primarily with ballads, in which music and aesthetics are in the foreground.

“From time to time a legend has emerged that Asbjørnsen left a number of recorded folktales which, due to schoolmaster-like narrow-mindedness among those who supervise his papers, have not been made available to the benefit of everyone,” writes Reidar Thomas Christiansen in the Introduction to Brudenuggen og andre (1943; The Tailor and the Bridegroom and Other Tales).

Zoologist, later appointed state forest-master, Per Christian Asbjørnsen (1812-1885) and theologian, later bishop, Jørgen Moe (1813-1882), whose publications in the 1840s became a model for future folklore collectors, recorded erotic material in their notebooks – it did not, however, get into print. There are a number of pencilled notes in the margins with comments such as “unsuitable” and the like. Many of the texts collected were not even properly registered, and have since led a partially anonymous and furtive life in specialist archives. It is said, however, that Asbjørnsen enjoyed telling a racy tale – off the record – in jolly company and, every so often, his listeners would be protesting, but perfectly cheerful and attentive, young ladies.

In 1883 some Norwegian texts “with the decided smell of bedstraw” were published in German in Kryptádia (Secret Things), a journal for erotic folklore. In 1943 a bibliophile club in Oslo published thirteen copies of a collection of erotic texts, Brudenuggen og andre (The Tailor and the Bridegroom and Other Tales). In 1957 folklorists Laurits Bødker, Svale Solheim, and Carl-Herman Tillhagen followed this example and published a Scandinavian collection; the book, which was published in both a Danish and a Swedish version, but was not published in Norway, contains eight Norwegian ‘smutty’ stories.

“The envelope containing his original records […] has vanished from the archives of the Norsk Folkeminnesamling [Norwegian Folklore Institute], and no one knows what has happened to it. Nor does anyone know when it vanished, but its abduction says something about the popularity of the contents,” writes Oddbjørg Høgset in the article “Eventyr med skinnfellukt” (Tales with the Smell of Bedcovers).

The folklorist Oddbjørg Høgset compiled Erotiske folkeeventyr (1977; Erotic Folktales), the only available collection of the older, unedited, genre of skjemteeventyr. Oddbjørg Høgset explains how the suppression of sexuality in the Norwegian national treasure trove was actually like a mystery to be solved; she had to be a detective hunting down the shelf envelope from the archives in which Asbjørnsen’s recorded folktales for Kryptádia had been kept. That is to say, the shelf envelope existed, but it was empty. Rumours about its content circulated in folklorist circles, and “[u]pon closer investigation, it emerged that it had apparently last been seen in the early 1950s,” writes Høgset. It took her approximately five years to track down copies of some of the elusive Asbjørnsen texts.

“Hardly had I entered the valley, before a middle-aged Norwegian in fine national costume approached […]. ‘Welcome among us, compatriot! […]’ he said in his pithy, dependable dialect […]. Thord, that was the name of my host, was a tall broad-shouldered man with a singular face which, I know not how, seemed to me to resemble the ancient woodcuts of our Norwegian kings,” we read in Mauritz Christian Hansen’s short story “Luren” (1819; Eng. tr. “The Shepherd’s Horn”).

Even though this coarse material is something ‘everyone’ in Norway has heard but not read (until the late 1970s), we are actually dealing with a covert tradition – and it was a female researcher who found it opportune to bring it out into the public light of day.

Intermezzo

Until the present day, there have been few female researchers and collectors in the Norwegian folkloric tradition. However, we cannot ignore the work of pastor’s daughter and singing teacher Olea Crøger (1801-1855) who, in the 1840s, made a large and important contribution to the collection of ballads and folk tunes from Telemark County in south-eastern Norway. She sometimes collaborated with clergyman and hymn writer Magnus Brostrup Landstad (1802-1880), who was also an amateur folklore collector.

Olea Crøger was helped by her insider knowledge of the village milieu. There was certainly a difference of class, but she had grown up in the village environment and thus she did not have the city-dweller’s detachment from the informants. Many stories were told about her solicitude and popularity, and it is obvious that this had a positive impact on the delivery of the oral tradition material.

Olea Crøger’s name is mentioned in professional specialist contexts, but her contribution is nonetheless rendered partially invisible. As a woman – and a challenger to the professional scholars engaged in collecting folklore – she had difficulties getting her material published, despite backing from Jørgen Moe. Landstad’s Norske Folkeviser (1853; Norwegian Folk Ballads) included some of her material; she is thanked for the folk tunes she contributed and for her assistance in other respects.

Most of Olea Crøger’s original records disappeared, however, after she had passed them on, and they have never been found. Her fortunes in this respect parallel Oddbjørg Høgset’s story of the mysteriously empty envelope.

“All Bark, No Bite”

The husband in the well-known folktale about “Kjerringa mot strømmen” (Woman against the Current) wants to cut the corn, whereas his wife wants to shear it. The text is not classified as erotic, nor does it use any coarse language. In the covert tradition, however, the art of innuendo is also a point unto itself.

In the heat of verbal battle, the wife stumbles on the bridge and falls into the river. In the very moment of death she is seen to make shearing motions with her fingers; the man is so furious about their dispute that he is tempted to hold her head under the water so as to silence her bad-tempered and incomprehensible contrariness: “‘Shall we cut the corn then?’ he said. ‘Shear, shear, shear!’ screamed the crone.”

She then drowns, forced down by his hand. Some time later it occurs to him that she should probably be buried in consecrated ground, and so he goes to look for her body. His search proves fruitless until, that is, it strikes him that she is undoubtedly just as obstinate in death as in life. Quite so:

“And over the river she floated that same evening, in supreme defiance of gravity,” as the poet André Bjerke wrote in the 1960s of this seemingly primeval-female element in the Norwegian national mind:

[…] that we have bred on our domestic shores

a saint of freedom, greater than Jeanne d’Arc.

She was of a kind who have a mind of their own,

for she was born contrary by principle.

She is of a kind I would gladly have known.

The best in us comes of her stock.

Is this so? What is “the best in us”, and who are “we”? André Bjerke’s poem is a modern interpretation championing the right and power of individuality to remain unaffected by all manner of outside currents. A bourgeois ego-ideal compatible with maintaining one aspect of the national-romantic spirit, a spirit in which the folktale is located: the tales are traditionally seen as Norwegian cultural treasures; they are cited as evidence of a surviving, Norwegian uniqueness of mind after the “400-year-night” of playing the humble partner in a union with Denmark.

In a sense, the handed-down oral tradition, especially the folktale, represents every Norwegian’s dream of freedom. The hero above all heroes in Norway is young Askeladd (Ash Lad), a boy who triumphs in the most hopeless of situations by means of creative guile and cheeky daring. He is the lad from a poor background who battles his way through life; he is the enslaved individual who wins independence. Parvenue par excellence. The leap to the hero in “Mage” is, however, not that big.

Material in the folk tradition is, of course, international. We know far more about this today than was the case in the mid-nineteenth century. At that time, however, the historical and cultural situation in Norway was such that the collection and publication of folktales had special status.

Norwegian Speech – Disciplined Danish Writing

Mid-nineteenth-century Norwegian readers came for the most part from the official class and the educated bourgeoisie, or they were students – all people associated with positions of societal power. They had strong affiliation with the Danish urban culture and also with the written Danish-language tradition, which was still the benchmark. The perception of education and culture was associated with Danish writing, not yet with Norwegian writing, and as of yet only a few books of fiction were published in Norway. Almost a generation after 1814 and the dissolution of the union, it was still not considered particularly fitting to infiltrate the soberly measured Danish language with Norwegian dialects and oral style: this would be seen as sloppiness in the use of high and low style, demonstrating a lack of sophistication.

Both Asbjørnsen and Moe had grown up in contact with mixed social environments, but they were both university educated and were thus representative of the upper classes. The language and ideals of this group was the base from which they met with the bearers of tradition in the countryside. Most of the informants spoke one of the many rural landsmål dialects (lit.: language of the land), which in written language today are amalgamated in Nynorsk (Norway has two written languages: Bokmål, literally book language, and Nynorsk, literally New Norwegian). The folktale collectors circumvented these dialects in a rather perfunctory manner. The published tales were turned into ‘proper’ literature, accommodating the contemporary aesthetic requirements. This is, of course, understandable; however, the particular Norwegian style of folktale, with its directness and orality, was nonetheless allowed to shine through.

A similar exchange occurs in Hans Christian Andersen’s story about “Klods-Hans” (Clumsy Hans) – but in a subtle version: “‘It’s terribly hot in here,’ said the suitor. ‘That’s because my father is roasting cockerels today,’ said the Princess.” And that was a comment to silence Klods-Hans’ unfortunate brother and the other “cockerels”.

Publication of material characterised by regional ways of speech was not merely provocative in terms of a few stylistic views on aesthetic qualities, it also resonated deeply in the ongoing and heated cultural-political debate about the nature of a Norwegian language. The shaping of language had – and has – a central position in the national consciousness of the Norwegian people. Stated bluntly: how could you possibly be Norwegian in Danish?

From the 1830s-40s onwards, a distinctively Norwegian use of language with a less convoluted syntax gradually took hold. The use of rural dialects in the process of Norwegianising was also provocative on a societal level: farmers might indeed have attained political influence, but they were not accepted as a class. Nevertheless, there was a purely linguistic reason for looking at the peasantry in the light of Norse saga literature. The ‘Sunday peasant’ presented in national-romantic literature involved a degree of upgrading. The rural proletariat was thus attributed characteristics associated with Snorre’s heroic kings, but this was done in a superficial and somewhat arrogant way and from the perspective of the know-it-all sightseer. Material from the oral tradition, collected from the peasantry and villagers, was welcome for the sake of ‘national spirit’, but moderation had to be applied when it came to concrete, folksy utterances.

When Asbjørnsen and Moe published their first collection of folktales in 1844, one of their critics was the writer Camilla Collett. Like so many “Danomaniacs”, she found the folktales crude, representative of “the original rawness”.

She later changed her opinion. Despite ‘improvements’ to the texts required by the times, publication of the folktales made for a linguistic upheaval that was to be of crucial significance for Norwegian prose writers. They could thus, in one respect, defend their special Norwegianness.

Slapstick and Shame

Collectors and scholars were more concerned about origin, nationalism, and ‘the national mind’ than about who was doing the telling, in which milieux and why. As was the case elsewhere in Scandinavia, they carried out their work with a Grundtvigian purpose of enlightenment. This was hardly consistent with linguistic, not to mention carnal and ‘moral’, decadence. This was not the Norwegian People wanted by the educationalists.

The borderline between the published, acceptable slapstick and the ‘smutty’ stories is fluid: the often overtly violent humour and satire in the more acceptable stories has sexual undertones or is associated with the body’s waste products, and the language in a number of stories was consciously adapted and ‘improved’ by the publishers. Popular terms for genitals, and everything that can be linked with the region below the belt, and direct mention of sexual intercourse and infidelity was, of course, beyond the pale for the bourgeoisie.

The publishers thus had to adapt the material according both to stylistic norms and to notions of decency. The reading audience was, therefore, of a quite different nature than the speaking or disseminating persons. The cultural clash between, on the one hand, the official classes and urban middle classes and, on the other hand, rural culture and peasantry, ran very deep. Viewed as a history of writing and of culture, the evolution of folktale texts reflects the disparate nature of the empirical premise of the various social classes.

“Prinsessen som ingen kunne målbinde” (The Princess No-one Could Silence) is a famous example of editorial folktale ‘improvement’ as applied, in a sense, both to women and to sexuality. The princess’s sharp tongue frightens off one suitor after another. The king promises that the man who can get the last word in will also get his daughter. It is perfectly clear that the princess is not prepared to accept just anyone. Per and Pål, older brothers of the quick-witted Espen Askeladd, become all flustered and quite speechless when, during their initial conversation about how hot it is in the room, she retorts: “It’s hotter up my arse.” For them, the battle was lost.

In the medieval Laxdœla saga (Laxdale Saga), Melkorka does indeed voluntarily choose silence after she has been abducted from her father, the Irish king. However, the sexual prank was also a feature in olden times, as can be seen for example in Boses saga (Bose’s Saga), published in a new edition in the 1970s. At that time, the more folkloric light literature was disdainfully called “stepmother stories”.

However, take a look and we will find that this remark is nowhere to be seen in the general edited versions that have been the popular reading for so many years. Neither fair copy nor princess can, in all decency, use such terms, so Asbjørnsen and Moe make it warmer in the glohaugen – the baking oven or open fire. This might well, in the literal sense, be correct, and it is undeniably a more decent remark, but any logic with regard to outmanoeuvring the suitors is now hard to find.

To be fair, it should be added that informants too were tempted to smarten up the terminology when confronted with the town-dwelling folklore collectors. Many a note records that the narrator had declined to tell the story concerned, but had been persuaded to do so. The archives also include notes in which obscenities have been methodically deleted.

The “Askeladd”, who by untraditional means manages to silence the mouthy princess, did not actually start out as the Ash Lad – he was originally the far less flattering “Oskefisen”, the Ash Fart: someone who fans the ash (blows on the embers to keep the fire going, or quite simply, lets off), someone distinctly generous with their own wind!

Sex and Symbol

Experience and tradition tell women to mind what they say and let the other party take the lead. The apocryphal Lilith was banished to the demons when she ‘spoke up’ to Adam, and countless folklore heroines in old myths or literary variants are banned from speaking or punished with enforced silence. Psyche, in Apuleius’ story (in the ‘novel’ The Golden Ass), is beautiful as a statue and therefore virtually inhuman. She is given away to a supernatural being, but she is not even allowed to see her lover, the ‘monster’. He mates with her in sensual delight, anonymous in the darkness of night, but she must never attempt to see his face and never answer other people’s questions. Total isolation.

Apuleius’ version of the story, which shares some features with the Norwegian variants “Østenfor Sol og vestenfor Maane” (East of the Sun and West of the Moon) and “Kvitebjørn Kong Valmon” (The Polar Bear King), incorporates a dispute between Venus and her son Cupid. The mother wants to put a stop to Cupid’s love for a mortal woman. She is intensely jealous. In the end, however, Cupid is restored to favour, and the young couple have a daughter, named “Voluptas”, meaning ‘pleasure’ or ‘bliss’.

Sexuality is far more covert in the magic folktales, not to mention Hans Christian Andersen’s literary “Vilde Svaner” (The Wild Swans), in which the lovely Elisa with her vow of silence risks her life in tenacious, self-tormenting endeavours to save her brothers from their stepmother’s curse which has turned them into swans. Or the little mermaid who pays for her human form by exchanging her tongue for a painful pair of legs. Mute submission contra fatal speech. And it all seems dazzlingly pure and innocent. Inspired by folk tradition, but sorrowfully beautiful in rendition.

The castrated man sometimes takes revenge, resulting in a special variant of female silence: “[…] and before she knew it, he bit off her tongue”, as is told in “Den sløge guten” (The Sly Boy), Erotiske folkeeventyr.

In other words, magic fairytales, and the kunsteventyr (Kunstmärchen, art-tales) they inspire, produce girls with a sex appeal fairly similar to that of the modern Barbie doll. Like blonde wheat fields, they comb their innocent hair while awaiting autumn and harvest. But there is a stirring in the wheat…

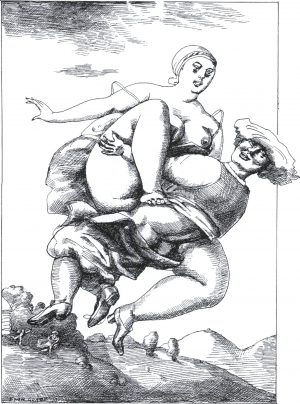

The young women in the fairytales have often been abducted and have fallen under the spell of a monster. The spellbinding motif is here, as in the ballads, clearly erotic. Locked away, the young woman has to ‘de-louse’ the troll’s or the ogre’s hair; she sits with the giant’s head in her lap. The first secret meetings between the girl and her hero and rescuer could also be summed-up thus: he lies across her lap, and she ties a gold ring in his curls. This might indeed, purely in terms of the language, be a case of de-lousing, but the intimacy is striking. A pact is made.

The ‘lie-in-lap’ motif is most likely a transformation of a scene of sexual intercourse; a figurative idiom that is also evident in older literature. We are familiar with Shakespeare’s Hamlet, boldly asking Ophelia if he should lie in her lap. There is no mistaking the purpose of his suggestion.

In the Norwegian recorded folktale about “Ålsvart og Ålkvit” (Ålsvart and Ålkvit), the gygra (female troll) uses this motif with deceitful, seductive intent: “‘May I warm myself with you,’ she asked. ‘Yes, you may,’ he said. So she laid her head in his lap. ‘Will you de-louse me,’ she said.” Afterwards, the boy has to take some of her hair and use it to tie up the horse and the dog. She then transforms into his wicked stepmother (!) and kills him, the animals being unable to come to his rescue.

It would be possible, without the help of psychoanalytical interpretations, to name many examples of such erotic ambiguity. The long golden hair itself can have a double function: yes, what was that about the “cunt gilder”, the man who shaved the hair of his female victims…!

Silence and Corporeal Threats

“Kjerringa mot strømmen”, which opposed male authority, and other seemingly chaste short stories and skjemteeventyr might well be far more closely linked to a highly mortal and corporeal merriment than we would at first suppose.

The woman who goes against the current is certainly not particularly pious (cf. André Bjerke’s virgin comparison), even though, after her death, a place within the churchyard walls is planned for her. Nor is she cultured. She shouts and screams until she trips and falls, she simply takes a plunge… But this happens after her clipping fingers have in fact been aiming at the man’s nose.

We might indeed speculate about what she is actually objecting to with her seemingly absurd remarks. Her defiance and verbal obstinacy stems from a different part of the body, which just happens to be spotted between her snipping fingers. There is no need for much more thought in order to make out a kinship with other bodily ‘excrescences’, despite the fact that the ‘nose’ euphemism is indirect and is not necessarily interpreted in a sexual sense. The tradition shows that this (mis)interpretation is possible.

On the surface, “Kjerringa mot strømmen” also makes humorous fun of a woman who is foolish and ignorant of a specific work procedure; her words intrude on the man’s area of expertise. Her husband, therefore, is to all appearances quite within his rights when he uses force and strength to compel her silence; the text does not dispute this. He subdues her and forces her under the water – without this taking the edge off the humour.

This folktale is one of a series of texts showing how the parameters of marriage make the man vulnerable to danger. The wife is a threat to his authority and right to make decisions. The tale “Mannen som skulle stelle hjemme” (The Man Who Kept House) shows another side of the same coin. Everything goes completely wrong when, in the absence of his wife, a man attempts to take care of the daily, female pursuits – role reversal, in other words. Not totally unlike that implied above, but this time converted into action. Towards the end of the story, the man is hanging in an undignified fashion down the chimney with a rope around his foot. Moreover, he not only loses his footing, tethered as he is to a cow dangling from the roof outside, but he is also pulled into an elongated cavity. Rape. And there he is stuck, caught in his own trap, until his wife comes home. Doubly ignominious!

The folktales thus suggest a castrating connection between women’s speech and men’s control. The male is ‘led by the nose’. Sexuality and womanliness make, as is well known, a threatening cocktail for the man’s identity and dominating position. This is not an observation that will surprise us unduly, being basic knowledge in our day and age.

The folktale “Verkefingeren” (The Swollen Finger) deals with mother and daughter: “‘God help you, my daughter,’ said the woman and threw up her hands in horror. ‘Now you have lost your honour, too.’ ‘I don’t give a shit about an honour that sits so close to my arsehole, oh no,’ said the girl.”

The story about “Den seje pølse” involves the ‘parents who must look after their daughter’ in the pattern. Here, too, castration is a key point – along with a ‘food-transformation of desire’. The ‘thing’ must, in keeping with tradition, be called by its proper name – and it is quite all right to use an inflated caricature. At the same time, there is a metaphoric cover-up going on by means of a point of similarity: the sausage shape. Well yes, that’s a joke we all know. Dangerous sexuality converted into innocent desire for food? No: it is the young woman’s father who eats the sausage. In all its suggestiveness, we here have a case of far worse ‘things’ than a well-known exterior similarity; the situation is orally incestuous, indirect but palpable.

Desire can assume many forms; hunger for food, for verbal meaning, or for the union of human bodies. The crude stories mix the various levels in such a way that they generate representations of the most fundamental cultural taboos, as we know them from the Bible and from ancient myth: incest, cannibalism, and symbolic patricide, besides adultery, perversions, and promiscuity.

In his mid-nineteenth-century sociological studies, the exemplary Eilert Sundt writes of night courtship: “[…] when it is found that they are true to each other […] none of their acquaintances will blame or criticize them in the slightest. For this is the custom of the country in many of our rural districts and the only way by which young people of the servant class can become ‘acquainted’ […]. This nightly courtship is naturally always extremely dangerous for flesh and blood.” But he writes that the rules are nevertheless strict, albeit different from those in the towns. He had to learn the practices and ways of thinking, he writes, in order to understand the population being studied. Om giftermål i Norge (1855; On Marriage in Norway).

Beneath the Surface

In the opinion of some folktale scholars, the theme of the danger of sexual relations made its entry into popular culture when the Roman Catholic Church warned its priests against involvement with women: celibacy was the ideal – at all events, destructive sexuality should not be visible on the surface.

However, the ecclesiastical, and in addition extremely bourgeois, view of humankind’s carnal inclinations contrasted strikingly with the rural community’s view of the body and of sexual relations. The fact is that men and women in rural Norway, far into the second half of the nineteenth century, lived in a physical and verbal proximity which, viewed from the outside, might seem highly immoral.

Night courtship and sexual relations before marriage were quite normal, albeit neither wanted nor necessarily approved of. Such things were usually only condemned if infidelity and deceit were involved. Parents could accept that their daughter’s boyfriend spent Saturday night in her chamber, and he would even be invited to breakfast on Sunday along with the rest of the family. But the prerequisite was faithfulness.

“It was, to a large extent, tolerated that servants had sexual relationships. [… It was also] common for couples to have sexual intercourse without being married,” writes Anne-Marit Gotaas in “Det Kriminelle kjønn. Om barnefødsel i dølgsmål, abort og prostitusjon. Bidrag til norsk kvinnehistorie” (1980, eds. Anne-Marit Gotaas, Brita Gulli, Kari Melby and Aina Schiøtz; The Criminal Sex. On clandestine childbirth, abortion, and prostitution. Contribution to Norwegian women’s history).

Servants often slept in the stable and many slept in the same room, perhaps even in the same bed. It was not unusual for the young women to get pregnant by their workmates. In the 1840s – the decade during which the extensive collection of folklore material and dialects was made – a large number of children were born outside wedlock in the Norwegian countryside. This made for much misery and hardship among women, as substantiated by the high incidence of induced terminations of pregnancy. It was, all in all, a tough decade for poor people. History tells of numerous infants born clandestinely and then killed by their mothers. Up until the reform of criminal law in 1842, induced abortions and infanticide were capital offences, although the common practice had, over the course of time, resulted in most cases ending with reprieve.

The Danish ”mage” can mean both “such a thing” or “the like” and “mate”, as in partner or lover – a word play used actively in the story.

Most people knew about this sexual activity outside marriage, but were not shocked by the practice. A ‘loose’ lifestyle might not be desirable, but many had no alternative.

The financial situation at the time was not auspicious for people of humble means who wanted to get married: the number of jobs in the 1840s, for example, did not correspond to the number of able-bodied marriageable men, and, moreover, weddings were expensive. Some couples therefore lived together without getting married, and some young women managed to support their children as single mothers. This was not looked upon favourably, but there was a degree of tacit consent to the situation. Servants were completely at the mercy of their employers’ good will.

These circumstances were part of the folktale informants’ empirical world and, as such, naturally had an impact on the material narrated. The individual who does not know his or her social place will be exposed to ridicule in the skjemteeventyr, and the public official (king, clergyman) who exploits the poor will be taken to task. The stories inject carnival humour into everyday life, so that dismal realities can be tackled with the help of ribald laughter; they cross the frontiers of taboo by detailing particulars of genitalia and sex life to the extremes of absurdity: in a perfect intercourse between rebellion and acknowledgement of various aspects of the social order everything seemed permissible, even the very foundation of society could be subjected to implicit threat – but only, that is, in the skjemteeventyr.

“And they lived happily…”

The folktale must end happily – that is a virtually cast-iron criterium. This also held true for the erotic skjemteeventyr. Happiness is, in other words, to be able to “shear”, in and after death too. Or when – oh, sweet revenge – both of the clergyman’s women lie back, legs parted, a couple of fools left on the floor in the wake of the folk-gilder Suchathing. Or even: a castrated young man and a cruel, sausage-munching father.

In this type of text, happiness is not a case of ‘getting one another’. Happiness is more likely to be found in the boundless laughter that permits the impermissable, but which nonetheless consolidates the fundamental community code.

To express this with an alliterative line from Norwegian children’s verse: “live life lustily laughing.”

Translated by Gaye Kynoch