In 1647 the Dutch artist Karel van Mander painted a large full-length portrait of Christian IV’s daughter, Leonora Christina (1621-1698). The countess was depicted in a modern flowing gown with pearl trimmings and, following the English fashion, she wore her hair loose; the little velvet hat was a special sign of her noble descent. To Leonora Christina’s right, van Mander had placed a symbol of fidelity, a fawning little dog, and, to her left, a larger dog or wolf that she is affectionately stroking with her fingertips. This tame wolf symbolises her husband, Corfitz Ulfeldt.

“The flame became a rose that blossomed on her [Leonora Christina’s] breast, and became one with the heart of that noblest and best of all Danish women. ‘Yes, that is indeed a heart in Denmark’s arms!’ said the old grandfather.”

(Hans Christian Andersen: “Holger Danske”, 1845)

The dog featured as a symbol of fidelity in countless seventeenth-century portraits of women; it had been a wife’s heraldic animal since Reformation times. The small fawning dog was thus a kind of standard accessory, a familiar and conventional symbol, whereas the tame wolf was a more personal symbol linked specifically to Leonora Christina. The canis fidelis features in Leonora Christina’s life as something other and more than purely conventional female symbolism. Faithfulness was an important spiritual and moral yardstick: a principle on which she had to take a stand and by which posterity would judge her – for better or for worse. By means of her writing she wanted to demonstrate that she possessed the virtue of fidelity, a moral raison d´être for the seventeenth-century woman. The tame wolf, Corfitz Ulfeldt, proved to be more volatile than ‘tame’, however, particularly in the second half of its life. Leonora Christina did not abandon the wolf, but she succeeded in turning faithfulness to Ulfeldt into faithfulness to herself in the roles of king’s daughter and noblewoman, exiled lady of high rank and “Cristi Korsdragerske” (a bearer of the cross of Christ). In van Mander’s painting she can touch the wolf affectionately: both Ulfeldt and fidelity would be at her disposal.

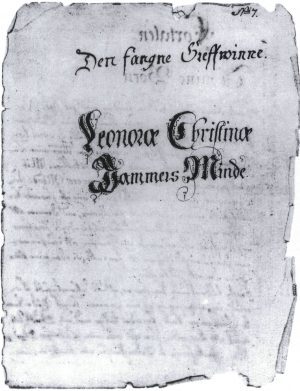

Until the mid-1800s, the Danish public was unaware of Leonora Christina’s Jammers Minde (Memory of Lament, her memoirs written while she was imprisoned in the Blue Tower, 1663-1685). When the young librarian Sophus Birket-Smith first published the work in 1869, it proved to be a huge hit with a delighted readership interested in all things historical and national; it even became highly fashionable to name girls after the Danish heroine. This fervour had barely subsided when, in 1888, art historian Julius Lange was the first to label Jammers Minde morally reprehensible. Jammers Minde was categorised as harmful popular reading, given that Leonora Christina put allegiance to Ulfeldt higher than allegiance to the state and the concept of justice.

“We all admire faithful Leonore Christine, but assigning her to rule land and realm with Korfitz Ulfeldt in her wake, that we dare not and ought not,” wrote Aage Westenholz in a letter to Karen Blixen’s brother, Thomas Dinesen, dated 1921. Westenholz saw the Ulfeldt couple as a chilling comparison vis-à-vis Karen Blixen and her husband, Bror von Blixen-Finecke. In 1921 Bror was well on the way to plunging the famous African farm and also Karen Blixen’s Danish family into financial ruin. Leonora Christina may indeed have been an admirable woman and a national treasure, but fidelity – a quality that was, according to Westenholz, the truly female side of her personality – made her an awful warning as well.

“Nature emptied its rivers in your blood.

As bride and mother you bit back, but alone you were gentle.

Bold in your shift, you bared your teeth, she-wolf.

Your memory of lament is to us a miracle of strength.”

(Johannes V. Jensen: “Leonora Christina”, 1906).

A heart in Denmark’s coat of arms, a heroine, a writer who put the nation’s morals in jeopardy, a true woman, a complete and rounded human being, a scheming traitor – there is not exactly a dearth of modern and old historical, moral and literary depictions of Leonora Christina. It is long since her autobiographical writings have been taken as a historically accurate account of the power struggle following the death of Christian IV in 1648. But the desire to reveal her intrigues and untruthfulness has not diminished. Even though Jammers Minde no longer convinces anyone of the innocence of the Ulfeldt couple, it does convince us of Leonora Christina’s abilty to use the seventeenth-century woman’s most important virtue, fidelity, in her existential project: to survive existence in the void – the Blue Tower – and transform her shame and degradation into moral triumph.

“Frederik drew Corfitz into a window recess and whispered something, but Leonora stayed where she was and passed a loud comment on the Queen’s conspicuous lack of conversation. Sophie Amalie flinched, and she began to talk. Only in German, of course. Only on uninteresting topics. She’s probably good at embroidering monograms, thought Leonora as she turned to the English ambassador and embarked on a conversation about Francis Bacon.”

(Helle Stangerup: Spardame (1989; Queen of Spades).

An Exiled Noblewoman

– Leonora Christina’s Earliest Writings

In 1651 the Ulfeldt couple left Copenhagen in haste. Frederik III had taken steps to examine Ulfeldt’s accounts. As prorex and rigshovmester (Minister of Finance) under Christian IV, it had only taken Ulfeldt a few years to become extremely wealthy; he must have feared Frederik III’s inspection of the account books given that he and Leonora Christina decided to flee to Sweden. In the years following their escape, Leonora Christina began writing short pieces of prose and autobiographical narratives.

Leonora Christina was very well-qualified to write. She had been taught German and French during her childhood, and in the early years of her marriage she had continued to take language lessons, trying to learn Latin and Italian, although she did not consider her progress in Latin to be particularly good. She found pleasure in translating the modern French pastoral and heroic novels of the day, and she received instruction in music and painting. When young, she had been a veritable Renaissance woman who made a virtue of having many strings to her bow and being able to play on them all. In accordance with the Renaissance ideal of “uomo universale” (i.e. the universal man, or polymath), she applied her proclivity for accomplishment to many areas: painting, music, embroidery, academic studies, ball games, distillation, pickling and, of course, writing.

“She had at that time an unusual memory. She could at one and the same time recite one psalm by heart, write another, and attend to the conversation.”

Leonora Christina writing about herself in her first autobiography.

Her first extant short prose piece “Ded som jeg singulier udi Kong Karls regering i Sverrig haver funden” (What I Alone Have Found in the Court of King Karl in Sweden) was written in 1654 about the wedding of the Swedish king; it was perhaps intended to be part of a longer description of the court. Following a brief account of the wedding ceremonial, Leonora Christina comments on a number of unfortunate details: the presiding clergyman nearly dried up, the bride did not give her responses at the right moments, the envoys were not conducted from the celebration in a manner befitting their rank, and discussion arose amongst the bride’s ladies about their placing in the entourage. Leonora Christina is keen to show that she can judge whether or not everything passes off correctly. Together with Ulfeldt she had visited the European royal families, scoring a personal success at the leading court,289 Leonora Christina the French, and she was not going to forget her expertise in etiquette when writing the short wedding report.

Leonora Christina was unlikely to have witnessed the ceremonial in person. The Resident Minister from Denmark, Peder Juel, wrote that Leonora Christina and her sister Hedvig “were not at the wedding, since they were told that in all the ceremonials they were to walk behind the Queen’s ladies”. Leonora Christina obviously did not consider this position in the entourage to be appropriate to her station.

However, Leonora Christina did not have the opportunity to continue her court records. She and Ulfeldt took up residence in Pomerania, which at the time was a territory under Swedish control. Ulfeldt did not manage to achieve any particularly influential position at the Swedish court, and so in 1656 he decided to try for reconciliation with Frederik III. Leonora Christina was sent to Korsør in Denmark, but had to return empty-handed. Shortly afterwards she wrote her account of the journey: “Relation du voyage de madame la comtesse Leonora Christina; faite en Dannemark, l’an 1656, au mois de novembre” (Account of the Journey Undertaken by Countess Leonora Christina in Denmark, the Year 1656, in the Month of November). Like her description of the wedding, the travel report survives in her handwritten manuscript and is, apart from the title, in Danish. Leonora Christina is the first-person narrator; she describes with humour and dramatic sense how she came to Korsør and there met her half-brother Ulrik Christian Gyldenløwe. Half-sister and half-brother did not enjoy a warm relationship. Gyldenløwe’s mother, Vibeke Kruse, had lived with Christian IV after his divorce from Leonora Christina’s mother, Kirsten Munk. Leonora Christina and Ulfeldt had been personally responsible for ensuring that Vibeke Kruse was banished from Rosenborg Castle immediately following the death of Christian IV. Leonora Christina’s arrival in Korsør proved a splendid opportunity for Gyldenløwe to retaliate: “[…] I recalled there had been some dispute between our two houses”, remarks Leonora Christina casually. The story about Vibeke Kruse is not mentioned, and Leonora Christina merely notes that it had undoubtedly caused Gyldenløwe no discomfort to inform her that Frederik III would not receive her.

On the journey home from Korsør, Leonora Christina suspected that the Prefect in Flensborg was planning to arrest her. His servant tried to bring her carriage to a halt. “Whereupon I said to him that he could no doubt reason for himself that if I could possibly help it I would not allow myself be held, and would above all defend myself for as long as I could.”

She paints a picture of Gyldenløwe as her absolute opposite. He comes across as an ostentatious, foul-mouthed and utterly unintelligent upstart, whereas her behaviour is that of a dignified lady of rank, of “Qualiteter” (i.e. class). The point of Leonora Christina’s account of her journey is that her attempted reconciliation failed because her application to the king had to be conveyed via ludicrous and incompetent messengers like Gyldenløwe. In her description of events, Leonora Christina avoids direct self-characterisation and instead makes a show of composure, authority and competent energy. It is apparent that the prose writer Leonora Christina has learnt from her favourite picturesque French, Italian and Spanish heroic novels.

A third minor prose piece, “Hvad som passeret udi den confrontation her udi mit hus i Malmø den 17 dec. 1659” (What Occurred During the Confrontation Here in my House in Malmö on December 17th 1659), which has survived in a fair copy probably made by Leonora Christina’s daughter Anna Cathrine, describes court proceedings intended to clear up the issue of Ulfeldt’s complicity in a conspiracy against the Swedish king. The plot would have returned Malmö to the jurisdiction of the Danish king, and Ulfeldt was charged with having told the Danes about the Swedes’ planned assault on Copenhagen in 1659. Ulfeldt was pursuing a, to put it mildly, hopeless political agenda. He was trying to safeguard his own position and did so by allying himself with Swedes and Danes in turn, but all he achieved was to be accused of treachery by both parties. “Confrontation in Malmö” describes the cross-examination of witnesses against Ulfeldt and the other defendants. Ulfeldt was not in court. He had suffered a stroke, and Leonora Christina took charge of his defence. Her account of the confrontation demonstrates an acute lawyer’s mind in command of all legal hairsplitting and details. She pounces on contradictions in the witnesses’ statements and renders it probable that some of the witnesses had been threatened with torture.

“Fortify him, for I believe he is in need of assistance”, was Leonora Christina’s sarcastic comment about one of the witnesses who was unable to remember the testimony he had been instructed to give.

The testimony of the principal defendant, Bartholomeus Mikkelsen, against Ulfeldt was weakened by Leonora Christina’s quick responses, intelligent points and ability to make sure she always had the final word. The trial ended with Ulfeldt having his property confiscated and being condemned to death, although the court would not serve the sentence while he was incapacitated by illness. However, fear of the sentence made the Ulfeldts decide to flee Sweden. The couple agreed that Ulfeldt would go to Lübeck, while Leonora Christina would go to Copenhagen and attempt yet again to appease Frederik III. However, with his usual talent for making the wrong decision, Ulfeldt chose to travel to Copenhagen too – where Frederik III simply had them both arrested with no further ado. Leonora Christina told the story of their unsuccessful flight in her French autobiography, which she wrote in 1673 in her last prison, the Blue Tower of Copenhagen Castle.

French Heroine

Leonora Christina’s First Autobiography

Leonora Christina’s first autobiography was a lengthy piece of prose dealing with her life up until she was imprisoned in the Blue Tower in 1663. Written in French, the work survives in a manuscript – discovered in 1952 – in Leonora Christina’s own hand. She writes a somewhat halting French, with grammatical errors and a limited vocabulary. Her French autobiography is, nonetheless, piece of literature that is both entertaining and ambitious.

The actual motivation for the work was political and tactical. The autobiography was intended as a means of exerting pressure on the Danish crown. The historian and archaeologist Otto Sperling Jr. had the idea that Leonora Christina and his father – the physician Otto Sperling who was also imprisoned in the Blue Tower, convicted of being Leonora Christina’s accomplice – should write autobiographies. Otto junior was working energetically to secure their release, and he thought that perhaps the autobiographies would influence the opinion of European royal circles in favour of the two prominent prisoners. In the second half of the seventeenth century, autobiographies of noted and famous personalities were all the rage at royal courts across Europe. The Sun King himself, Louis XIV of France, wrote autobiographical texts; Renaissance culture’s general interest in the individual’s experience of self and surroundings could be most excellently satisfied by the moving and tragic autobiographies of two wrongfully incarcerated persons of rank. The inside story, written by a king’s daughter known throughout Europe and her intimate friend and physician, would surely make an impression. Otto’s plan was not entirely successful, but in the late 1600s various copies of the autobiography were circulating in French, Danish and Latin, and Otto used Leonora Christina’s text when preparing his manuscript De foeminis doctis (On the learned women), which was, however, never published.

In this autobiography, Leonora Christina portrays herself as a French heroine and woman of rank. She writes about herself in the third-person as “notre femme” and approximates her self-portrait to heroic biographies along the lines of the Frenchman Brantôme’s Memoirs of illustrious men and women he had known.

The Ulfeldts were taken to the castle of Hammershus on the island of Bornholm. They were released in 1661. In 1663 Frederik III learned that Ulfeldt had offered the Danish throne to the Elector of Brandenburg. Leonora Christina was arrested in Dover, England, and taken to the Blue Tower, where she was incarcerated for the next twenty-two years. Ulfeldt escaped.

“It would weary you to tell you of all that passed at Borr…[Bornholm]”, remarks Leonora Christina before embarking on an account of her imprisonment at Hammershus; with a sure sense of narrative tempo and narrative technique, she selects a number of dramatic and illustrative episodes from her life. She wants to demonstrate that she is in possession of favourable human qualities such as courage, dignity, self-control, intelligence, physical and mental stamina, and talent for rapid and astute repartee. The heroine of the tale already commands these qualities when but a child. The autobiography is not a story of development or bildung. The heroine only changes by means of increasing her learning and adding to her skills. She places particular importance on her self-control. She never allows herself to become angry; “Elle se moc” – she ridicules those who offend her.

Only one occurrence, the death of her father Christian IV, causes her emotional distress. She kneels down before the King and weeps as he says to her: “Je t’ay mise si ferme que personne ne te peut branler” (I have placed you so securely that no one can move you). Leonora Christina succeeded in painting a picture of herself as the King’s particuarly gifted favourite child. She deftly avoids telling us about her father’s dramatic divorce from her mother, Kirsten Munk, and about the bitter dispute between Ulfeldt and the King in his final years.

The image she creates of Ulfeldt is interesting, because in this she cannot suppress many of the factual events and mistakes, but has to enter the realm of psychological description and self-interpretation. “At the age of seven years and two months she was affianced to a gentleman of the King’s Chamber. She began very early to suffer for his sake.”

Leonora Christina sets the theme of her suffering from her very first presentation of Ulfeldt, but she also emphasises that Ulfeldt was a loving husband: “Her husband loved and honoured her, enacting the lover more than the husband.” Loving husband he might have been, but Ulfeldt lacked the breadth of outlook and the energetic action that she possessed. This first biography in French gradually became the story of how Leonora Christina time and again had to save Ulfeldt from his own deficient judgement, erratic moods and naive political performance. Being the narrator, Leonora Christina can make sure she appears to every advantage, and this she does. The weak and erring Ulfeldt is forever putting her into dangerous predicaments, but it is precisely in these situations that she really comes into her own. Loyalty to the husband chosen for her by her father tasks her doubly: she must cope not only with Ulfeldt’s enemies, but also with Ulfeldt himself.

Leonora Christina’s happy marriage was an exception in her family circle. She stresses the fact that her siblings were envious, and that they attempted to undermine her good marital relationship by offering Ulfeldt whores and by telling him that she had admirers.

Yes, Imprisonment Leads to Heaven

– on Jammers Minde

The difference between the fully-formed heroine of the first autobiography and the confessional first-person narrator of Jammers Minde is plain to see. However, the two works share Leonora Christina’s use of fidelity as a factor in the interpretation of her life. “I suffer for having loved a virtuous lord and husband, and for not having abandoned him in misfortune.”

By the time Leonora Christina wrote the preface to Jammers Minde – in 1674, after eleven years of imprisonment – she had reached a clear picture of how she should understand the series of dramatic events and misfortunes into which she had been led by her loyalty to Ulfeldt. Degradation, shame and misery in the dungeon become meaningful when she starts seeing herself as a “Cristi Korsdragerske” (a bearer of the cross of Christ), a female Job, chastised and loved by the Lord God. She can make her balance sheet of suffering tally exactly with that of tried-and-tested Job, and so she writes triumphantly in the preface: “Verily, He has freed me from six calamities; rest assured that He will not leave me to perish in the seventh.”

The six calamities in the narrative of her sufferings are:

flight from Denmark 1651,

journey to Korsør 1656,

confrontation in Malmö 1659,

imprisonment in Hammershus 1660-61,

loss of power and property,

arrest in Dover 1663 and, finally,

the seventh calamity: the Blue Tower.

The ability to see a divine order and meaning in the sudden ups and downs of life is not unique to Leonora Christina. It is found in abundance in the work of the Baroque hymn writers, including Thomas Kingo and Dorothe Engelbretsdatter. The new society that developed under the absolute monarchy of Frederik III provided opportunities for a speedy career – and also for an unforeseeable fall from the pinnacle of power. The idea of a divine stability and order was a form of defence against the new and perilous mobility and inconstancy that came to characterise life for some subjects of the absolute monarch. However, whereas the first-person in Kingo’s and Engelbretsdatter’s hymns is every Christian person, created as man and woman, Jammers Minde is a personal and individual confession and narrative of crisis. The work was a new and radical version of the seventeenth-century autobiographical and humanistic literature, but also had features in common with Catholic legends of pious hermits and with seventeenth-century existential religious writings on the soul’s communion with God. In her role as “Cristi Korsdragerske” Leonora Christina is the pious hermit who endures her Passion, her sufferings, and who experiences the liberation of her soul. The spiritual progress in Jammers Minde is suggestive of La noche oscura del alma (1578; Dark Night of the Soul) by San Juan de la Cruz (Saint John of the Cross).

“[…] for sense and spirit, as if beneath some immense and dark load, are in such great pain and agony that the soul would find advantage and relief in death. This had been experienced by the prophet Job […].”

San Juan de la Cruz, La noche oscura del alma (1578; Dark Night of the Soul).

Leonora Christina describes how the state of accusation and despair is succeeded by silent attentive listening to the word of God. Like San Juan de la Cruz, she goes from mighty and desperate emotions into a quiet moment of religious contemplation:

“When I had long thus disputed and racked my brains, and had also wept so bitterly that it seemed as if no more tears remained, I fell asleep, but awoke with terror, for I had horrible fancies in my dreams, so that I feared to sleep, and began again to bewail my misery. At length God looked down upon me with his eye of mercy, so that on 31 August I had a night of quiet sleep, and just as day was dawning I awoke with the following words on my lips: ‘Mein Kind, verzage nicht, wann du von Gott gestrafet wirst; dann welchen der Herr lieb hat, den züchtiget er. Er stäupet aber einen jeglichen Sohn, den er aufnimmt’. [My son, faint not when thou art rebuked of the Lord; for whom the Lord loveth he chasteneth, and scourgeth every son whom he receiveth.]”

Jammers Minde falls within a tradition of existential religious writings. Leonora Christina is not visionary and ecstatic like her Nordic female predecessor Birgitta of Vadstena. She is not allegorical like Spanish Teresa of Ávila (1515-1582) or moral-philosophical like her contemporary, the Swedish Queen Christina. Rather, she continues the male-dominated existential tradition of religious writing. Unlike Dorothe Engelbretsdatter, who seeks out female biblical figures with whom to identify in her hymns – Mary Magdalene, Deborah, and others – Leonora Christina follows in the footsteps of the male biblical figures: besides Job, she mentions Moses, Jeremiah, David and Jonah. When her gaolers use the ruse of appealing to her ‘female frailty’ in an attempt to make her confess her guilt, she retaliates by showing her strength and declaring that with “manly vigour […] Right valiant shall I be”.

“Oh Christ! Lord of the living,

Thine armour place on me,

Which manly vigour giving,

Right valiant shall I be […].”

(Jammers Minde)

The psychological backdrop to the series of male identifications into which she enters in prison, and in which she is ‘received like a son’ by God, is her relationship to her father, Christian IV. She sees herself as the King’s favourite child, far more gifted than her brothers and sisters. On a subconscious level she sees herself as the King’s son and heir. Given that she is precluded from earthly power, however, she can fulfill her assignment by being – not Christian’s – but “Cristi Korsdragerske”, crowned by God, the Father. Jammers Minde is the monument for her spiritual and moral triumph over her adversaries, the evil agents of power, the flesh ungodly.

“I have often said to myself: ‘Comfort thyself, thou captive one, thou art happy.’”

She transforms her prison into a biblical scene and her gaolers and personal opponents into players in her Christian Passion. Frederik III is not the actual villain of this drama. His mistake is that he lets himself be misled by scheming relatives, by his ministers and his provincial queen, Sophie Amalie, who wants revenge on the beautiful daughter of a king. In the biblical hierarchy, Sophie Amalie takes the role of Salome, stepdaughter of Herod Antipas, who demanded the head of John the Baptist. But just as Judas and Herod Antipas are necessary to Christ, the treacherous kin are necessary to Leonora Christina. In the role of “Cristi Korsdragerske” she has the advantage that she can entirely disregard the concrete question of Ulfeldt’s and her own culpability in treason. All this is merely an external circumstance giving rise to the actual and meaningful destiny: in prison, to find God. By virtue of the purpose and significance she assigns herself, she is able to open her eyes in the world of the prison and detect and describe her surroundings, her attendants and fellow prisoners. Jammers Minde thus becomes a dense and full description of life. This prison, in which prisoners were stowed away with a view to speedy disappearance into oblivion, becomes Leonora Christina’s habitat. She tells the stories of her female attendants, and via tales of their wretched lives she wants to show that in the Blue Tower she is forced to associate with women who have killed their children, with thieves and swindlers, but she also becomes absorbed by the material, by her own curiosity, and she writes detailed accounts of the lives of these women.

“She had two children, and it seems from her own account that she was to some extent guilty of their death, for she says: ‘Who can have any care for a child when one does not love its father?’”

Leonora Christina writing about her attendant Barbara.

While anxiety, whims, drunkenness, perplexity and fever plagued her female attendants in the prison, Leonora Christina stayed in good health. In 1682, however, she suffered from a gallstone, about which she was delighted to report: it was “composed of a substance like rays, having the appearance of being gilded in some places and in others silvered”. Leonora Christina also harboured ambitions of becoming an alchemist who could extract the philosopher’s stone from her own body.

While conditions in the prison cells were cramped, there was a spiritual space and a large narrative scope in Jammers Minde. Amusing and grotesque situations alternate with scathing exchanges of words, self-examination, spiritual admonition and notes about writing materials and handiwork. Jammers Minde is written with an eminent feeling for the subtlety and thrust of language.

Leonora Christina tells her story in Danish, for the most part. In the first section of the work she often translates the Low German, High German and French dialogue into Danish, merely noting in which language the conversations took place. She later begins to report dialogue in its original language, and in so doing adds another dimension to her various character sketches. She has the opportunity to score linguistic points off her opponents by replying in a language that they either do not understand or that outclasses them. Her hereditary enemy, Sophie Amalie, speaks High German or Danish in short, clumsy remarks; Leonora Christina’s few allies speak French and use it in intimate conversations or heartening letters. In its use of language Jammers Minde is a complex network in which the smallest detail is important to the rhetoric Leonora Christina creates from her life.

Leonora Christina endeavours to make Jammers Minde a testimony to her perseverance and mental strength, and she therefore tries to keep the reader in the belief that most of the work was written while she was imprisoned. Analysis of the paper and the handwriting has, however, established that two-thirds of the manuscript was written in the 1690s, when Leonora Christina was living in Maribo. Leonora Christina knew that the work would have a greater impact if it appeared to be an authentic account written within the prison walls, and thus she chose to present a fictitious version of its genesis. She was not going to let an opportunity slip; she had to draw on fiction and rhetoric to turn sufferings in the Blue Tower into passionate faith and storytelling.

Otto Glismann gives an account of the types of paper and writing in his article “Om tilblivelsen af Leonora Christinas Jammers Minde” (On the Genesis of Leonora Christina’s Jammers Minde), Acta Philologica Scandinavica, vol. 28, 1966.

Translated by Gaye Kynoch