My fearful soul’s foul wound

Reeks horribly

Into my Lord’s nostrils

Wherefore I now falter.

“Den Anden Sang” (The Second Song)

Even though Dorothe Engelbretsdatter paved the way for female hymn writing, lines such as these by Ingeborg Grytten did not rate among the most popular hymns of the seventeenth century. Nor are they to be found in hymnals of a later date. But these lines are taken from a hymn written by the first woman in Norway to follow in the footsteps of Dorothe Engelbretsdatter. Ingeborg Grytten often borrowed expressions from the Bergenian Deborah, as Dorothe was known, and she acknowledged her kinship with Dorothe’s hymn writing. Nonetheless, there are clear differences between the two hymn writers.

Time and again, Ingeborg Grytten conjures up lines dominated by her personal misfortune. She was of a later generation than Dorothe Engelbretsdatter, and she expressed life more directly in the verses of her hymns. She did not have as much honour to lose, and in terms of era she was closer to a more personally confessional Pietism.

It is not hard to imagine the hymn writer Ingeborg Anders-Datter Grytten (b. 1668) dressed in her dark clothes, disfigured, sitting in her chair in the gallery of Holmedal Church, western Norway, a chair which bears her name. Her father was the local clergyman, but Ingeborg Grytten did not mix with many people from her social class because she suffered from leprosy, and she did not mix with people from the surrounding villages because she came from the official class. What was more, she had an unusual interest for a woman: writing hymns. Loneliness was sometimes overwhelming, and this left its mark on her writing. In this hymn, for example, she asks to be allowed to die since all her friends have gone:

Must I longer wait for you

until it is your pleasure

To fetch me away from here,

and unharness me from my burden?

“Den Tiende Sang” (The Tenth Song)

However, Ingeborg Grytten had sufficient connections that forty-eight of her hymns were published in the collection Kors–Frugt (Copenhagen, 1713; Fruit of the Cross). New editions of the collection continued to be printed up until 1846. They were most probably written in the 1690s, and were approved by the censor in 1701. Kors–Frugt presents readers and singers with a universe that has a compact uniformity to its manic and dark depictions of life. Tenets relating to the sinful life are repeated in a confessional style:

As soon as I opened my eyes to the world,I began to sinIndecent sport was my game,To which Satan urged me on.“Den Anden Sang”

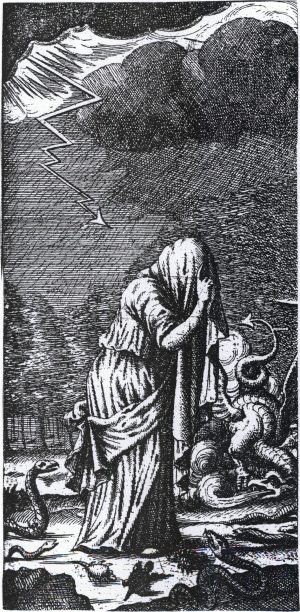

This outlook on life was closely bound to the dominant picture of the transitory and diseased body. Grytten viewed painful physical experience from a theological perspective: there is an intimate causal connection between the diseased body and the sinful soul, “Scourge of the Conscience”. In Grytten’s ideology, illness is a punishment for sin. The ill person is guilty. According to this line of thought, the good life begins once God has liberated the soul by means of the death of the body – “Mother Eve’s wanton Flesh”. The body is something from which we must be released, and yearning for death is thus an obsession in Grytten’s hymns. All things bodily are intrusively ugly and cannot be concealed.

Yet my abscess is

So exceedingly vile that I cannot

Hide my blemishes.

“Den Tredje Sang” (The Third Song)

Corporeal life is an exile from celestial life. Ingeborg Grytten’s hymns give this theme a biographical resonance that renders her verse more private than the poems of pioneering Dorothe Engelbretsdatter. We are closer to the intense pietist understanding of Christianity which characterised seventeenth-century devotional literature.

The most consistent compositional principle of the hymns is the division between life before and life after death. The good existence begins “When the soul separates from the body”. It will be heavenly when “The arid bones again flourish”. What more could one wish for, asks Grytten, “Than health restored from sickness and pain”?

Grytten’s first twelve hymns are cries for help in combating sin. The words “Sin”, “Sigh” and “Lament” are repeated in the titles of these thematic hymns. Thereafter, God and king are given their ritual hymns of praise, before the year is framed by verses for Christmas, New Year, Easter and Ascension. The Ascension hymn is strikingly private, and is characterised by the particular yearning for death voiced by Ingeborg Grytten.

Then it is the turn of everyday life. Each day of the week is framed by morning and evening hymns. Each weekday is also equipped with a song of penance, in which Grytten consistently depicts life in idealistic, but penitential, terms. There is no realism here. The morning hymns all thank God for having kept a careful watch throughout the night, so that the ‘singeress’ was able to sleep easily. This is followed by a prayer for the day just starting and an intercessory prayer for the ‘neighbour’. The ending confirms God’s omnipotence and idealises life in heaven. The day passes equally well, if the evening hymns are to be believed. God is present, even though one never escapes “the wily Tempter”. The question, then, is whether God will be present through the night. It seems as though he has to be persuaded and reminded how kind he has been earlier:

As you today and all my days

Have been a true father to me

Then I ask you, gentle Jesus

not to desert me

In this night, but stay by me

So I come to no harm

In soul, property or body.

“Aften-Sang om Løverdagen” (Evening Song for Saturday)

Ingeborg Grytten’s hymns pose a question concerning the nature of the sins about which she constantly sings. This is not something that the hymns deal with in much detail. The sins we do hear about are primarily linked to the senses of speech, hearing and sight. The most frequently committed sin has to do with daily conversation, which is suspect and called “Loose Chat”. Nor are ears put to better use:

Alas how are the ears pricked

Trying to hear vain chat.

“Aften-Sang om Søndagen” (Evening Song for Sunday)

The desire of the eyes is that they “On the madness of the world, become wickedly infatuated”. The life of the mind is not blameless either. Everyday life can easily fall victim to the influence of Satan’s thoughts.

By and large, what we can find out about Ingeborg Grytten, one of Norway’s two seventeenth-century poetesses, has to be gleaned from her hymns. We do not even know the year of her death. But we know that she was familiar with Dorothe Engelbretsdatter’s Siælens Sang–Offer, because she borrowed material for her melodies from it. Thus the west coast of Norway produced the first two female Norwegian poets. They came from the same supernational clergy class that was, at the time, the custodian of writing – and of women’s writing too.

Translated by Gaye Kynoch