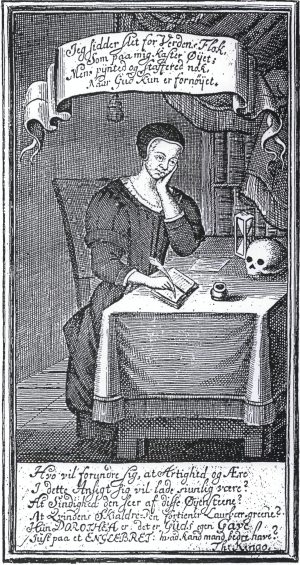

Dorothe Engelbretsdatter (1634-1716) is known as the first female hymn writer in Denmark-Norway to assume a sermonising poetic voice representative of the genre.

Her verse found its way into the oral and popular tradition, the realm of most women, as well as the ceremonious, male-dominated and learned house of God. Depictions of the virtuous and the female were themes that linked low and high, the nursery and the church. Unlike her male poet colleagues, Dorothe Engelbretsdatter had no other occupation than that of writing. She faced the God of the old ‘estate society’ not as bishop, officer, or schoolmaster, but as woman. Estate society defined woman on the basis of her sexual and social function in relation to the man. She was wife or spinster, virtuous or of easy virtue, and in all cases excluded from the patriarchal professions.

Dorothe Engelbretsdatter drove a wedge into this male society. The good woman is not merely virtuous, she is also active and creative. She can follow the art of writing as a profession. If she is going to cross the boundary of traditional female pursuits and write verse, then she must show quite emphatically that she is not also crossing any other boundaries laid down for the decent woman.

Writing by a woman was in itself borderline seduction. It was unusual for women to publish poems in a forum that was, in principle, accessible to anyone who could purchase and read. Dorothe edited her verse carefully, and she also pointed out that her work was created by a clergyman’s widow. Publications by women caused a stir.

Dorothe Engelbretsdatter was of course controversial in her day, and contradictory characterisations of her were numerous. She was often acclaimed as the wise and bold goddess on Mount Parnassus. Some settled for characterising her as a cry-baby, for in their opinion not even rivers as wide as the Nile and the Rhine were as abundant in water as was Dorothe’s pen. Dorothe Engelbretsdatter herself set great store by her “Riime-pose”, or bag of rhyme. Her poetry was of paramount importance.

She wrote between sixty and seventy hymns and prayers, mostly collected in Siælens Sang–Offer (1678; Song Offering of the Soul) and Taare–Offer (1685; Offering of Tears), a versified rendering of devotions. She also wrote between thirty and forty occasional verses, printed as single-leaf publications.

Dorothe Engelbretsdatter came from a Norwegian-Danish-Dutch family of clergy and military men. She was born in Bergen, on the west coast of Norway, on 16 June 1634. She married provost Ambrosius Hardenbeck in 1652; after his death on 13 June 1683 she spent the last thirty-three years of her life in widowhood. Four daughters and three sons died, while two other sons travelled in Europe, as soldier and student respectively, and never returned home.

Following the death of her husband and the loss of seven children, Dorothe Engelbretsdatter published Taare–Offer (Offering of Tears) in 1685. She had no contact with her two surviving sons after her husband died in 1683.

She ended up making her livelihood by writing, supplemented by a paltry widow’s pension. Dorothe Engelbretsdatter thus became an early example of the professional author who made her living through the pen. This was exceptional at the time.

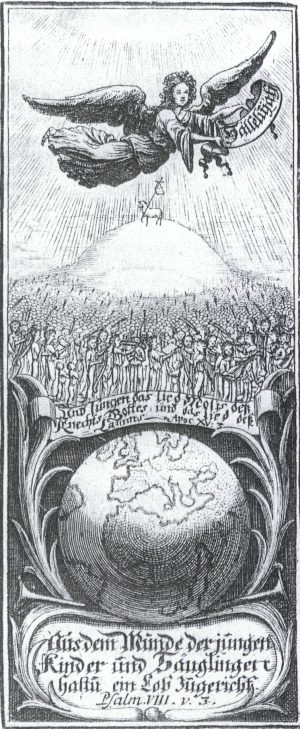

“The first emerged singing”

Siælens Sang–Offer arrived in song, wrote Dorothe Engelbretsdatter of her first work. When originally published in 1678, the work consisted of thirty-six songs that helped feed the almost insatiable appetite for singable material. Hymnals were literary bestsellers, and the books were swiftly sold and put to industrious use. This was particularly true of Siælens Sang–Offer, which over the following 210 years was published in thirty or so editions. In Dorothe’s lifetime it was reprinted seven times, including hymn book versions sold by the bookseller. She added new songs to each edition. By 1699 the work contained nearly seventy texts. Many of these were new variations of earlier hymns and verses of praise. However, she adhered to the editing principle that she had used since 1678, when the first eleven hymns were linked to ecclesiastical ritual and festivals, while the next twenty-five dealt with hypothetical states of the soul.

Siælens Sang–Offer accounts for the most common states of the soul experienced by the Christian in relation to God: there are hymns to be sung on various special days and for various special occasions; there are petitions to God – for morning and evening use.

“Each bird must twitter with its beak,

Its Creator to praise,

Why should my mouth not speak,

And dare the same?”

“Til Læseren”, Siælens Sang-Offer (“To the Reader”, Song Offering of the Soul)

The liturgical forum and devotional life also provided material for Dorothe’s writing. The question here is how the Soul, representative of all souls, meets the absolute God. This question is posed persistently, both in Siælens Sang–Offer and in Taare–Offer. The setting for the soul-encounter is fixed, with standardised roles, following the orthodox norms.

At times, Siælens Sang–Offer presents concentrated and intense hymns that point back in time to devotional mysticism as well as forward in time to individualised and fervent Pietism. The texts usually guided a female first-person to a meeting with the Saviour: an infringement of the strict and representative hierarchy of estate society.

Besides Bible reading, Dorothe Engelbretsdatter’s literary background probably consisted of popular devotional literature of the time, such as Johann Arndt, Paradiesgärtlein (1612; Garden of Paradise. Danish tr. Paradises Urtegaard, 1653) and Lewis Bayly, Praxis Pietatis (1646; Practice of Piety).

Dorothe Engelbretsdatter’s intimate friendship with God was also part of the greater scheme of things in her day. The Thirty Years’ War, plague, disasters, major fires, crop failure and the resulting hardship had to be regarded as circumstances beyond the control of human beings. To achieve better times, the writer responded with individual guilt and consciousness of sin.

For a female hymn writer it was particularly important to include the perspective of penance. The work that was unusual due to its female authorship was easier to accept if that female also preached submission, as in the hymn:

When you O! Lord chastise me,

Then I shall kiss the rod,

And protect myself with prayer and screams,

That none shall silence me.

Today, a hymn with a verse like this – the female voice, the heartfelt and intense sentiments – would give the impression of being exceptionally beseeching. It is rare to find a hymn text in which the watchword of subjection is stated with such intensity. The aim is to discipline the body, and to transform the raging “flesh”:

But if the wild flesh’s nature

Is to be awakened to obedience

Then under the rod it must be purged

Bowed and broken by hand.

The moral is:

He whose body is restrained,

He will cease to sin.

The call to submit to a reproving God is also a well-known feature of religious texts written by men within the Lutheran orthodoxy. Adversity and acute epidemics were, according to popular belief, God’s punishment, and revivalist movements calling for penance attracted followers in Britain, the Netherlands, and Germany. Dorothe made her contributions – in the “simple style” of the Norwegian west coast. Physical torment in the form of punishment or illness was part of everyday life. There was a clear awareness that evil was not limited to thoughts or conscience. Evil was corporeal. The seventeenth-century person always had ruin close at hand, and chastisement was a means by which to ward off perdition. Dorothe’s request is thus:

Make the rod soft,

do not strike too hard,

You know what I can endure.

(“When you O! Lord chastise me”)

The Second came “weeping bitterly”

Taare–Offer (1685) is a collection of devotions in verse, taking as its starting point the depiction of Mary the sinner in St Luke’s Gospel 7:36-50. In writing about the female sinner in Simon’s house, Dorothe also referred to selected passages from the Norwegian pastor Peder Møller’s Taare– og Trøste–Kilde (1677; Source of Tears and Solace). Møller’s book was itself a reworking of Thränen– und Trostquelle (1675) by Heinrich Müller, the popular theologian from Rostock. The trajectory from wretchedness to worthiness is central to the story of the sinner Mary, and in her work Dorothe Engelbretsdatter replicates this structure. Mary is fully aware that she has sinned and is unworthy. By means of various cleansing processes, by washing and kissing Jesus’ feet, she attains redemption.

In Taare–Offer the unworthy woman is a useful model, because she changes and becomes dutiful. The source material, written by the theologians Müller and Møller, is dominated by depictions of the wretched and shameless whore: evil, deceitful, coquettish, and untrustworthy. In Dorothe Engelbretsdatter’s version, repentance and the subsequent transformation are the central issues.

Dorothe takes the picture of the whore and from it draws new perspectives on Mary. Taare–Offer uses beseeching rhyme and rhythms to describe a woman plagued by fears, a woman who actively and generously opposes evil. She washes Jesus’ feet and she then dries, kisses and anoints them with ointment. If a woman who has been sexually active outside marriage is to become worthy, she must show repentance. In Taare–Offer, Mary’s tears are a campaigning strategy leading to reward and acceptance from the Lord. The tears have objective value and qualify Mary for a new status as worthy woman. She is the repentant woman who can change her situation and meet that which is divine. Paradoxically, tears thus become a metaphor for love. “She must have held Jesus dear, she who is so deeply affected. That love alone gushes from her eyes.”

In the first part of Taare–Offer, “Den Taare-gydende Synderinde” (The Weeping Female Sinner), tears are a metaphor for suffering: eyes bleed. Tears are a sign of despair: we hear about “melting away in tears”. And we hear about a state of childhood with God as mother:

Here stands the lost sheep, and weeps seeking comfort,

Like the child in tears craves the mother’s breast.

Suffering, powerlessness and love are united in virtue, with the aim of reaching God: “Make yourself felt to God” with tears, “they soar upward to the pavilions of heaven”. At first, Taare–Offer presents a kind of pre-verbal condition, in which tears are Mary’s only form of speech. Weeping has a healing and atoning power that allows the woman to melt into the deity. The worthy attitude in Taare–Offer is childlike and submissive. Sin, the repressed and the unconscious come into sight at Jesus’ feet. Jesus redeems. This is also the case with the penance programme in Lutheran orthodoxy. Early in Taare–Offer, speech and tears are presented as opposites:

The prayer with strongest sway is the one drenched in the colour of water

Although the lips might fail, God will lend you His ear

When the heart speaks purely your supplication will have strength,

For outward tongue-twaddle He has no high regard.

Tears are the characteristic of original and authentic emotions. Repentance is the basis on which speech attains a new status in the second poem: “Den Fod-Tørrende Synderinde” (The Feet-Drying Female Sinner). “Each bird sings with its beak,” we read, and it “will not kill you that a loud mouth grumbles some”. The third poem, “Den kyssende Synderinde” (The Kissing Female Sinner), discusses various legitimate and illicit situations as regards the kiss. The final song, about “Den salvende Synderinde” (The Anointing Female Sinner), confirms that the change has occurred. Now it is time for generosity, to give, kiss and anoint. “Your faith has helped you.”

In her interpretation of the Mary story, Dorothe Engelbretsdatter showed that female candour is not the same thing as arrogance. As soon as Mary let her generosity flow towards Jesus, she was accused of arrogance. The Master, on the other hand, received her gifts with pleasure, writes Dorothe, and claims that he did the same with the hymns she herself gave.

“Here There Are Too Many Writing and Railing Against One”

Controversy regarding Siælens Sang–Offer began in earnest in 1680-81. A number of students in Copenhagen had great problems accepting that a “Quinde-Hierne” (woman’s mind) could have been responsible for Dorothe’s hymns. Accusations were spread via flyers and gossip. In truth, it was alleged, Dorothe Engelbretsdatter’s clergyman husband, Ambrosius Hardenbeck, had actually penned the hymnal. What was more, Dorothe stole verse from other poets. However, Dorothe Engelbretsdatter was also championed by some younger men. Joachim Kaae from Bergen had personally made fair copies of verse from Dorothe’s hand. He furiously intervened in this early dispute about women’s place in literature, and called the instigators of the accusations of plagiarism: “Satan’s suckling spawn, their tongues rife with poison. No part has she appropriated from others.”

The idea of originality, of the authentic work and the original words, had also gained a foothold in the shaping of the common property: hymns and biblical literature. It was important for the verse to be acknowledged as an authentic “Dorothe Engelbretsdatter”: “Thou – knoweth,” she wrote to Jesus – “Searcher of the Heart” – “that this my Song-Offering has not grown upon my lips, but has sprung from my innermost soul and mind.” She took her principled defence from biblical models and from nature. It was God’s will that the birds should sing, because that is how he had created them. Women are part of God’s nature, and must be a part of God’s culture. Dorothe Engelbretsdatter was helped by receiving the seal of approval from a circle of learned men in Bergen, and by learned women and men in Copenhagen vouching for her work. In the publisher’s recommendation of Taare–Offer, Hans Wandall, later professor of Hebrew, praises the writer because she is one of the “prophetesses who simply put forward what is in keeping with the true prophetic word and our Christian faith and creed thus founded upon it”. This praise came after scholars, writers and the cultural elite of Copenhagen, from Anna Margrethe Lasson and Leonora Christina to Thomas Kingo, Jens Sehested and Peder Syv, and others, had expressed great appreciation of “a woman’s ingenuity” (Kingo).

However, when Dorothe made a trip to Copenhagen in order to arrange for publication of Taare–Offer and a funeral oration for her late husband Ambrosius, other male imaginations were also inspired – her trip provided fertile soil for speculation about clandestine love. These stories made the virtuous Dorothe furious. She responded via lampoonery, calling for the castration of the men who had such thoughts. In the end she had to resign herself to foregoing her trips to Copenhagen and staying at home in Bergen.

A number of the verses at the end of Taare–Offer can also be read as an allegory of Dorothe’s struggle for Siælens Sang–Offer – a critique of those who like to put other people’s houses in order.

It would be best for each,

Only to carry his own sack to the mill,

And give oft-repeated mind to

How he himself may thrive,

Lest the sorrow of others

Turn him grey before his time.

Mary encounters opposition from the male scribe when she unreservedly showers Jesus with gifts from her “nebb” (nib or beak). “He is truly of angelic purity,” writes Dorothe ironically, thus lashing out at the learned men who treat her woman’s writing with suspicion and with accusations of verbosity. Be the female central character called Mary or Dorothe, reserve and irony are fixed ingredients in the texts, thus highlighting that these creative women are divine.

“Gifted Goddess Bold”

Despite initial scepticism, Dorothe Engelbretsdatter’s style of writing, her preaching and the image of women she presented made her popular and well-liked by learned and unlearned alike. People were amazed by her ability with rhyme, and they laughed at her satire and the quick repartee with which she responded to accusations against her. Dorothe Engelbretsdatter played along when invited; for example, in Copenhagen, sitting next to Thomas Kingo at the dinner table, she improvised rhyme and puns on “a liver”. Endorsement from the Danish bishop, poet and hymn writer Kingo was crucial to her acceptance by other learned men. Acceptance in Copenhagen was particularly important to her: there she met and heard about poet colleagues, and the city had the beginnings of a literary milieu that was open to experimentation with the old rhetorical configurations and to the art of writing as practiced by women.

Thomas Kingo’s advice to Dorothe Engelbretsdatter’s critics:

Go take up her spinning wheel,

You slothful lads,

Who will not study,

Begin you then to spin

Go sit you down

And heckle hemp and flax!

While she doth admirable work

with pen and mind.

(From Thomas Kingo’s laudatory verse in Siælens Sang–Offer, 1685)

Experimenting with form was not, however, on Dorothe’s agenda. She stayed safely in the familiar Baroque environment.

Among the religious books left by Dorothe Engelbretsdatter were works by the Royal Danish Philologist Peder Syv (1631-1702), in which the Danish language is seen as an extension of the “Adamic” language used by the first humans. This philology was rooted in theology, but studies with a broader base were also underway. The emergence of good rhyme and excellent writing in the native language – by, among others, pioneers such as Anders Bording (1619-1677) – made it easier for a talented clergyman’s wife with no great proficiency in Latin, to write and attain a position on the Norwegian and Danish Parnassus.

One summer’s day in 1680, Petter Dass (1647-1707), a poet who would later achieve fame, arrived in Bergen; he had journeyed from the north of Norway, one of his intentions being to procure a copy of Siælens Sang–Offer. Dorothe had to give Dass a copy she had already promised to someone else, as she did not have any copies left and the booksellers had also sold out.

Gifted Goddess bold

Bold of pen, bold in ink

Bold in writing verse

Of nymphs there are nine,

One more, makes ten

That will be Dorthe.

Petter Dass to Dorothe Engelbretsdatter: “Tacksigelse for Bogen” (In Appreciation of the Book)

Petter Dass did not publish any poems in book form during his lifetime, but posthumous publication of his topographical poetry and Baroque hymns established his reputation as the foremost popular poet of his generation.

Dorothe Engelbretsdatter, on the other hand, enjoyed a prominent position during her lifetime.

Extant collections of music from the time show that the hymns were sung to a variety of tunes – her texts were favourites with the composers.

Acknowledgement as a poet, a good network and her family background of learned Danes, Estonians, Dutchmen and Norwegians gave Dorothe a sense of pride and self-assurance. The literary credit she received meant that she started to call herself a professional writer, and she even invited other “Dicte Søster” (sister poets), such as Anna Margrethe Lasson, to “mit Lau” (my guild). Lasson was given pride of place among the honorary poets in Taare–Offer, and Dorothe also developed the idea of the community of women in her defensive rhetoric for womankind. God “gives His pound of grace to all, / In this way I became an example for women / The Lord has you, and me given this special designation.”

Self-assurance and position also meant that early on, albeit after a bitter struggle, Dorothe Engelbretsdatter was granted a license by which she decided who might publish her poems. While Petter Dass would have been happy to find a publisher, Dorothe was the victim of spurious editions of Siælens Sang–Offer. Christian Cassube, a businessman in control of both a publishing house and a number of bookshops, realised that the general increase in reading skills would lead to an increase in book sales – not least, of hymn books. He reprinted Siælens Sang–Offer and was not particularly careful with the accuracy of the rhyme, the order of the songs or the choice of melodies. He did not know that he was dealing with a woman who considered writing to be her profession. She demanded total control of the work she saw as an extension of herself: “It pains me to the marrow,” she wrote of Cassube’s erroneous print, that “my song-offering I offered God, should be so shamed for the sake of insatiable people’s worldly profit.” On 11 July 1682, because of Cassube’s faulty reprint, Dorothe Engelbretsdatter was granted a royal license for ten years, and a fine of one-hundred rigsdaler (rix-dollars) was levied on each spurious copy. Dorothe Engelbretsdatter was granted a new license to her books in 1692.

A greedy, deceitful, shameless knave

Has secretly printed this book

And thus rendered his masterpiece,

He deserves to suffer ill fortune.

Alas, long-fingered printer

Foul disorder make your wretched claws

The profit lies close to your heart

So God’s word is printed with no diligence.

“Æredigt over Trykkerens berømmelig Gierning” (Poem in Honour of the Printer’s Illustrious Business), first two stanzas.

“With a Pen Burnished in Tears”

In her dedication to Queen Charlotte Amalie, Dorothe Engelbretsdatter cites anxiety as her reason for writing Taare–Offer. Her reduced financial situation led her to ask the King and Queen for exemption from taxation while she visited Copenhagen in 1684-85. Her picture of the tax bailiff could be taken from real life:

I, when anxiety dominates

in my mind like a torrent,

Am so fearful of the tax-collector

As of the bogeyman himself.

(The Mightiest and Exalted Monarch Christian the Fifth)

Dorothe was exempted from paying tax. She was not, after all, a wealthy woman. Ambrosius’ estate had not amounted to much:

Of an eternal nature were the things my husband most collected,Of wealth I am free, likewise of poverty.

Dorothe’s writing thus brought with it financial privileges. She did not end up as a poor little clergyman’s widow who had to find a new husband to provide for her needs. She recognised early on that the status of “Poetess” gave her a unique commercial lever in her contemporary society. She had no formal schooling, as far as we know, apart from the education she received at home from her father, who was a school teacher and later clergyman. She knew, however, a thing or two – German, for example, and some Latin.

In sixteenth-, seventeenth-, and eighteenth-century Norway there was little sense of a national consciousness. Unlike most of her writer colleagues, Dorothe Engelbretsdatter signals that she is Norwegian when she wants to distance herself from the Copenhagen gossip and point out that she is a natural wellspring of rhyme. The profession was dominated by poets who wrote in Latin, and who mainly worked to commission rather than writing to be published or to sell books. The Norwegian nobility were not writers. The country folk had a rich oral tradition of storytelling, which was now gradually being recorded in writing. Dorothe Engelbretsdatter was appreciated because she wrote verse that fitted in with a popular, religious tradition. Scholarly theology, philosophy or geography – the common themes for books – were not her field of expertise.

She also had a local narrative tradition on which to base her work. Bergens Kapitelbok by Absalon Pederssøn Beyer (1528-1575) was an account of everyday life in Bergen, a subject that Dorothe also addressed in her occasional poems.

From 1678 to 1888 there were between twenty and thirty published editions of Siælens Sang–Offer.

It is quite extraordinary that by 1685 – in the course of just six years – her melodious poems had been published in the same number of editions as the Bishop of Funen, Thomas Kingo (1643-1703), had managed in ten years with his Aandelige Siunge–Koors. 1. Part (1674; Spiritual Song Choir, Part One).

Posterity’s verdict on Dorothe Engelbretsdatter has followed a distinct pattern. Negative judgements of her work were dominant in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. When originality became fashionable in the nineteenth century, her verse was deemed rather unoriginal, the view being that she was too much under the influence of the preacher Johann Arndt and the hymn writer Thomas Kingo, while others explained away her literary status by saying that male interest was more concerned with the sex of the writer than with the words written. Her irony was considered vulgar; her satire – Dorothe Engelbretsdatter’s best and most witty form – was seen, in terms of the later norms for what was considered womanly, too crude. Nor did Dorothe Engelbretsdatter succeed in maintaining her reputation as a “poetess”. She had too many feelings, they said, too many words. She was “the kind who could talk a great deal”, and anyone could quickly conjure up “a hundred verses like that”. She was too mystical, too strict, too intense and, in particular, too female. A female first-person voice singing “without restraint”, as if women represented everyone, was only considered acceptable for a brief period of time; mere decades, in fact.

Today, two of Dorothe Engelbretsdatter’s hymns, “Afften Psalme: DAgen viger og gaar bort” (Evening Hymn: the Day Retreats and Passes On) and “Om det Evige Liff: OM Verden med sin Glæde sviger” (Of the Eternal Life: Of the World with its Deceitful Pleasures), are in Norsk Salmebok (the Norwegian Hymn Book). Her Christmas carol “Paa Jorden Fred og Glæde” (Upon the Earth is Peace and Joy) is still sung, and folksong circles continue to sing verses from the pen of worthy Dorothe Engelbretsdatter. Not many have appreciated her beseeching, repetitive, almost modern rhythms or the mysticism and unrest in her bag of rhyme. One need look no further than the selection of hymns collected in Norsk Salmebok to spot Dorothe’s concrete and sensuous images and evident awareness of her predicament. The situation is alarming:

Should Crosses from all corners look,

Gazing onto me.

(“Om det Evige Liff”)

Four planks [i.e. a coffin] are my attire

In which I shall be laid out

With a sheet and a little more

I own not a feather.

(“Afften Psalme”)

The first “She-Poet in the Lands of the Hereditary King” saw the person and the cause, virtuousness and writing, as one and the same thing. “To write verse, to ride a horse/ Bravery in battle / That ever befits the man best/ Is no honour to women,” wrote the poet Tøger Reenberg (1656-1742) of Dorothe in his Forsamling paa Parnasso (1699; Assembly on Parnassus). Dorothe Engelbretsdatter’s writing advocated the virtuous female pen, and thereby began process of turning the pen into a tool not exclusively reserved for use by men.

Translated by Gaye Kynoch