In the 1480s, two pious and zealous men by the names of Jacob Sprenger and Heinrich Institoris travelled around the Rhineland, endeavouring to rouse the public and the authorities to help combat a new heresy that, in their opinion, had already spread like a plague through large swathes of the Christian community. However, the local populations and ecclesiastical authorities showed so much antipathy to the project that the two monks found themselves compelled to apply to their father the Pope: could he not use his authority to get things moving? And that he could. In the papal bull Summis desiderantes affectibus (Desiring with Supreme Ardour), which he issued in 1484 in response to the request, Pope Innocent VIII wrote that “[i]t has indeed lately come to Our ears,” that a large number of people were using accursed charms and crafts to slay infants still in the mother’s womb and the offspring of cattle, spoil the produce of the earth, hinder men from performing the sexual act and women from conceiving. All because they had abandoned themselves to the devil or one of his accomplice demons, the so-called incubi and succubi, through which Satan gains access to and control over a person’s life.

The Pope not only blessed the activities of the two Inquisitors, “Our dear sons”, but instructed all authorities, ecclesiastical and secular alike, under liability to punishment, to make every effort to combat this lethal threat to the Christian community.

It turned out that the pestilence was more widespread and tenacious than initially believed. At first the problem was not simply that something was going on, but that the nature of this something was unclear. Indeed, in the early days it was perhaps even totally unidentified. It was all vonhörensagen: it had “come to Our ears”.

The witch persecutions did not start with Sprenger and Institoris. Supported by the papal bull and the later renowned Malleus Maleficarum (The Hammer of Witches), which the two men wrote about the phenomenon and published in 1487, the persecutions became institutionalised, and from then onwards secular and ecclesiastical authorities were obliged – whether they wanted to or not – to see it as their legitimate duty to get witchcraft under control. It took 300 years to do so. The last official witch-burning in Europe took place at the end of the eighteenth century. It is highly unlikely that the persecutions came to an end because it was thought that the ‘offence’, which the papal bull and Malleus Maleficarum had attempted to pin down, had been eradicated. The question remains, however, whether the aim of the process had not actually been achieved.

“And this appears to be the order of the process. A Succubus devil draws the semen from a wicked man; and … passes that semen on to the devil deputed to a woman or witch; and this last, under some constellation that favours his purpose that the man or woman so born should be strong in the practice of witchcraft, becomes the Incubus to the witch.”

(Malleus Maleficarum).

What, then, were they – the theologians, the Church leaders and the key agency – out to achieve?

Like other forms of heresy, witchcraft was quickly perceived and defined in canon law as a “crimen exceptum”, an exceptional crime, which meant that in terms of judicial prosecutions – and this is one of the characteristic features of inquisitorial procedure – the use of torture was permitted prior to verdict and sentencing.

The provision of the use of torture in cases of witchcraft is not so much a manifestation of sadism among ecclesiastical jurists as a manifestation of the nature of the Church’s interest in the procedures.

In Malleus Maleficarum, two circumstances in particular arouse the greatest agitation in the two good monks. First of all, female sexuality, whether a case of too much, too little or too singular. Indeed, every time they come across it – and this they do frequently and readily – the very fact that it exists generates a florid fury of words. This is most concentrated, of course, in the chapter explaining why it is chiefly this “fragile feminine sex” that is addicted to such kinds of “perfidy” (i.e. witchcraft). This is where the authors work themselves up to the persuasive and notorious conclusion: “All witchcraft comes from carnal lust, which is in women insatiable.” And they add, as a precaution: “See Proverbs: There are three things that are never satisfied, yea, a fourth thing which says not, It is enough; that is, the mouth of the womb.”

The other feature that disconcerts the two authors of the manual is – connected, unsurprisingly, with the first – the phenomenon they call “maleficium taciturnitatis”, the witchcraft of silence. It turned out that a number of women – despite being, as it were, ripped to shreds during torture – obstinately maintained their silence. Besides the recommendation to use any amount of torture, the importance of making the woman talk is apparent from the fact that the authors do not hesitate in their advocacy of lies and deceit during interrogations: the promise of acquittal, for example, or mitigation of punishment. She must confess, at any price.

The official arguments in justification of this murderous zeal were the need to find out about accomplices and the fact that by means of the ‘confession’ thus procured it might be possible to snatch the sinner from the claws of the devil. That line of reasoning was, of course, no more valid than most official justifications.

In Histoire de la sexualité: Vol. 1: La Volonté de savoir (1976; Eng. tr. The History of Sexuality, Vol.1: The Will to Knowledge 1977), the French philosopher Michel Foucault refers to confessional rites as a special technique or method through which first the Church, and later the establishment, acquire knowledge about, and thereby control over, its members. Apart from the fact that Foucault seems to forget or disregard any interest the various confessors might have had in confessing, it cannot be denied that in the European witch trials this ‘method’ evolves in one of its more overt and brutal forms. We can see from, for example, Malleus Maleficarum and the papal bull that it had become a key aim for the Catholic Church – as later for the Protestant Church and the secular administration – to obtain information about a psychological and social reality that had slipped through their fingers or, more likely, that they had never had a grip on anyway; a reality that was not yet incorporated in a common symbolism, in the language and self-perception of societal discourse. It became incorporated – in its own distorted way – by means of the witch trials. By means of the confessions.

By the time the Church, helped by the authorities, had built up its dogma on the phenomenon (recorded during the era of the persecutions in a number of learned treatises on sorcery and witchcraft), so that everyone knew what they were meant to believe, the matter lost its interest value. Or, rather, after a period of three hundred years in which women had been well and truly dissected, the desire to pursue witch trials had run out of steam. Most local communities, however, which had their own vested interests in the enterprise, could not understand this slackening off at all; in many areas – in Denmark, for example – independent lynchings and ill-treatment of ‘witches’ continued far into the nineteenth century.

Considered in that light, the confessions are not simply one of several components in the trials; they are – more than any other contemporaneous material – the very narrative generated by the trials.

A Danish Witch Trial

As actual historical and legal events, the witch trials are far from being one cohesive phenomenon. There are such wide differences in the trial processes and conceptual parameters that it is not possible to describe the procedures in a single account. The two following examples will therefore focus on the Danish trials.

The first extant record of a witch trial in Denmark is dated 1533; thereafter, the number grew steadily up through the 1500s, culminating in 1610-25. The last official witch-burning took place on the island of Falster in 1693, when two women were sentenced to the stake and a third was punished with exile for her activities as ‘wise woman’.

Anna Lourups

On 20 September 1619, Ole Andersen, bellringer in Ribe, appears in the town court and accuses Anna Lourups, an old lady living on alms, of having come to him two years previously and asked for some lead: “But when she received none […] she went out and said many bad words […] some time thereafter he became almost demented and would take his own life. He therefore charged Anna Lourups with being an out-and-out and incontrovertible sorceress.”

“For as she is a liar by nature, so in her speech she stings while she delights us. Wherefore her voice is like the song of the Sirens, who with their sweet melody entice the passers-by and kill them. For they kill them by emptying their purses, consuming their strength, and causing them to forsake God.”

(Malleus Maleficarum)

The bellringer then demands a surety from her guaranteeing that she will remain in the town during the trial; “otherwise clap her in irons”. No one, naturally, was willing to risk reputation and property for the sake of an old woman, so she wasimmediately arrested and put in “Finkeburet”, the town hall prison.

Once the bellringer has plucked up his courage and brought an action against her, a number of citizens suddenly recover their memories. At the six subsequent hearings in court he calls on twenty or so witnesses, whose troubles and misfortunes are now in large number attributed to Anna Lourups’ sorcery. One has lost his “mælkende”, his good fortune in milk production; others have seen their beer brewing spoiled; several have lost their cows; one has been taken “urgently ill and is now crippled”; another became “so strange that he jumped in a spring and would have drowned had there not been good people nearby”. All of which occurred entirely because Anna Lourups had pledged them “shame and adversity”.

Ole Klokker also gets hold of some rabble from the poorhouses who can testify that people shout “sorceress” at her and that, what is more, she keeps a strange establishment, “especially by night, when she runs in and out of her house”.

At the seventh hearing there is a call for “court witnesses”, “church council representatives” or “parish witnesses” in her defence, but of course not a soul steps forward – apart from, that is, Anna herself: “If Volle [Ole] Bellringer is the death of me wrongfully, then I shall write a song about him that will fetch him sorrow and vexation for as long as I live, and after that day he will never thrive and be happy,” and she will “spare no one, but will allege them all [to be witches]”. Although Anna Lourups is neither cowed nor silent but, on the contrary, holds her own throughout the entire trial with oaths and curses, all in vigorous rhythms and rhyme, her endeavours are to no avail. It seems that it is by holding forth that she poses a threat. A unanimous court jury sentences her to death by burning. This sentence was confirmed by Ribe Rådstueret (a superior court of justice presided over by the town mayor and aldermen), after which Anna “voluntarily and without torture” makes a lengthy confession and receives her final sentence. She was put to death shortly afterwards, perhaps even, as often happened, on the same day.

Anna Lourups’ case describes the typical procedure of a trial for witchcraft during the period, and she is a very good illustration of the Danish sorceress. She was usually of mature years or old, that is over the age of fifty; she was not necessarily a spinster, given that more than half of those accused were married or widowed. And she was, of course and above all, a woman. Between eighty and ninety per cent of all those accused, both in Denmark and in the rest of Europe, were women. Sorcery was a female profession, regardless of the fact that it was also practiced by men. Most of the accused were also more – as a rule – or less poor. Many were simply beggars. It is evident from the trial records that a large number of the accused had been a considerable strain on the local community. Their daily begging was a nuisance: it was impossible to “get rid of her”. And yet, of course, not every impoverished old woman was accused. Those who were charged were the ones who lived their life of poverty in a particularly incriminating fashion. Anna Lourups’ talent for converting her rage into pasquinades and lampoons might well be a little out of the ordinary, but the word, the evil tongue, played a major role in the popular experience of witchcraft. Much anger, resentment, complaint and fear emanates from the defendants; this is conveyed not only in the words of the ‘witch’, however, but also through her eyes, hand, the object she has touched – indeed, simply her very presence seems to have destabilised the daily rhythm of nature and community: “All the many times Bodil Harichs entered his house […] misfortune has always befallen them.” The new element was that it now became legitimate – based on a rationale developed beyond the local community – to prosecute and punish these women who refused to live amicably in their wretchedness.

The vile word was in itself the crucial agency of witchcraft. This belief in the ability of the word to create what it said also came to dictate legal procedures: having predicted something bad, which then occurred, was taken as conclusive proof of guilt in a witch trial.

Confessions

“Karen Roeds’ confession of witchcraft and its acts, as she has confessed to the Mayor and Council, August 4th 1620”:

“First Karen Roeds confessed that, about twenty-six years ago, Hans Frandsen had taught her the arts of sorcery in a small chamber of her house, into which she had entered with him, and there she renounced the Lord, and at the same time Hans Frandsen had given her a boy, named Svarting, who had straightaway come in to them in the room and was like a fresh fellow, and he had promised her everything she might desire […] and now the following have been received into the rode

A rode was a local league of witches, a kind of ‘coven’, which according to the confessions consisted of twelve to fourteen members led by a rodemester, often a man, just as men are also named in the other special roles, “drummer”, “piper”, “deacon”.

with her: first, Hans Frandsen’s illegitimate son named Jens Hansen, who is master of the rode; furthermore, Karen Kraghs, Johanne Moltesdatter […] an innkeeper who lived in Timmerby and who is a short, fat woman, pockmarked of face; her husband is a peddler selling soap and spirits, – yet another woman […] When her rode gathered them together, they met on the boat jetty and then they sped to St. Peter’s churchyard, and later to Vislef churchyard, and there they danced and drank together everything that their boys put their way.

“Likewise, Karen Roeds confessed that when her boy was with her he was sometimes a young man and sometimes a black dog […].

“Furthermore, Karen Roeds confessed that there was a man in Sønderho, named Søren, who fished; he tricked her out of some money and so she had her boy break his legs […] and further, Karen Roeds confessed that she was well aware that the woman who served Peder Claussen was going to take his manhood from him because he would not marry her […]. Furthermore, Karen Roeds confessed that she and Karen Jørgensen had raised the heavy storm a few years ago in which the many fishing boats foundered and people drowned […]. Further, the above-mentioned Karen Roeds confessed that last Whit Sunday she had some people visiting and that as she had no beer her boy served her up half a barrel of good beer on the floor of her chamber; he was clothed in black and was wearing knitted stockings, and since that time he had not returned to her.

“Present at Riberhus town hall on August 9th were the honourable and noble lensmand [fief governor] Sir Albert Scheel, the Mayor and Aldermen, and in their presence was also Karen Roeds, who voluntarily and without torture affirmed by her highest oath this her confession […].”

This account, from the records of Ribe Rådstueret, is one of the large numbers of confessions still kept in court archives around the country. The material used in the following section consists of transcriptions or complete summaries of confessions in sentencing ledgers and court papers, nearly fifty in all, ranging from a few lines to the equivalent of approximately twenty standard pages. The greater part consists of so-called “spontaneous” confessions, made “voluntarily” during the trials. It would seem, however, that many of the women were nonetheless subjected to “painful questioning” after judgement had been passed, whether as part of the punishment, as a facet of the judge’s mental hygiene, or in order to torture another few names out of them. At all events, a number of such confessions and namings of alleged accomplices, and catalogues of the sorcery with which they were charged, have survived. These statements are drawn on where relevant.

Read as a straightforward account of concrete events, the confessions do not make a great deal of sense. Most of them actually appear to be pure gibberish. But the current enterprise is not to track down or establish what might actually have taken place. The confessions will be read just as they are: as texts, produced in a specific situation, as a particular version of existing ideas concerning a specific subject or a specific figure, the sorceress. They will thus be viewed as a kind of oral tradition recorded in writing – not by gifted unmarried ladies of noble rank, but by more or less sober clerks.

Many scholars are of the opinion that the confessions are not the women’s own words, but that the words were put into their mouths during the trial by judges, prosecutors, priests and other good people. However, like every other confession – to the priest in the confessional, for example – these confessions were also generated via interaction between the person confessing and the person or persons to whom the confession was addressed. The content of the confessions is made up of various popular, ecclesiastical and learned notions on the topic, but the form is that of the actual lived experience of the confessional situation. It is indisputable that, in most cases, the accused has been forced to enter into these notions as subject; but the somewhat surprising eagerness to get everything said and elaborated now that she at long last has the word, or has gained a hearing, which characterises a number of the texts, makes it likely that for some of the accused, too, the situation served a purpose.

Key Elements of the Genre

“Firstly she confesses that the devil came to her one Thursday around midnight […] and said she would give him all that part she had therein [in the church] […] and she said to him that [she would] be his with life and soul […].”

“There is also, concerning witches who copulate with devils, much difficulty in considering the methods by which such abominations are consummated. On the part of the devil: first, of what element the body is made that he assumes; secondly, whether the act is always accompanied by the injection of semen received from another; thirdly, as to time and place, whether he commits this act more frequently at one time than at another; fourthly, whether the act is invisible to any who may be standing by.”

(Malleus Maleficarum)

The typical confession starts with this kind of pact. The main content thereafter is (cf. Karen Roeds above) an account of the life as sorceress into which the pact has initiated her, including the sorcery and evil arts she has personally practised over the years: “[S]he had cast a spell on Peder Christensen’s wife in Taaderup for that reason […]”; association with other sorcerers, mainly parties and communal acts of sorcery: “they assembled near Hessnæs and were there gathered a group of twenty”; naming of fellow conspirators: “these listed were in a rode with her”; and finally an affirmation on oath of the truth of the confession: “that she upon this confession would die”. Not every confession contains all these elements – some have more, and there is generally a large amount of individual detail – but they are the main recurring elements. They constitute the genre.

In Skøger og jomfruer i den kristne fortællekunst (1991; Harlots and Virgins in Christian Narratives), Birte Carlé writes about accounts of the holy harlots recorded in Latin in the compilation of texts known as Vitae Patrum (Lives of the Fathers). The work was first published in 1615, but the stories originated one thousand years earlier. Despite its title, the collection includes many comprehensive stories concerning women. Only three of these are found in the Nordic tradition.

The Pact

Apart from the confessional element in accounts of the holy harlots, these reports are the earliest confessional stories told by women in Danish. They were made in prisons and dungeons, or where the woman stood trial, and they paint a picture of someone who, at some point in her life, has found it necessary to reject the pact by means of which she was once enrolled into the Christian community – and at the time that meant the community per se – in order to enter another community. The point at which the new pact was made could be ten, twenty or even fifty years earlier – the accused might be in doubt as to the exact timing. Was it the day before yesterday, was it six years ago, or had she always been in a diabolical pact? It would seem that she entered the second pact in order to get what the first one would not give her. There is a recurring sentiment throughout the confessions: if she would renounce… and if she would serve…, then she would “get enough”. Enough of what?

The texts make it seem quite straightforward: enough food, power and sex – to put it in a nutshell. And the problem is not, of course, that the sorcerers want what everyone wants, but that they want it in a very particular way. They want it from the devil. The confession begins with the beginning, with the pact and its particular symbolism, which expresses the psychological basis of the behavioural pattern of the sorceress. The diabolical pact is the original scene.

“There is no doubt that certain witches can do marvellous things with regard to male organs, for this agrees with what has been seen and heard by many, and with the general account […].”

(Malleus Maleficarum)

“Thief and sorceress”

Getting “enough” in terms of basic material needs was quite obviously a key motive for the Danish sorceresses, a direct manifestation of the literal poverty and disadvantages that affected the majority of those charged. A large number of the accusations, and also of the guilty pleas listed in the confessions, deal with what could be called ‘theft-sorcery’, as in ‘theft-milking’ and ‘theft-churning’, cases in which the witch has used magic to drain the neighbours’ cows and churns of their milk and butter. This category also covers spells put on milk, butter, beer and crops: spells put on the processes by means of which humankind ensures the fundamental preservation of life.

The terms “thief and sorceress” and “whore and sorceress” feature frequently in the contemporaneous source material.

Butter and milk – besides being essential provisions of the time – were a manifestation of someone’s mortal wealth, indeed of that person’s prosperity in general. Almost identical terms are used in reference to taking butter or taking happiness from someone else. It might be bad enough to be robbed of food, but this more comprehensive theft is a phenomenon at the very core of the witch trials and the image of a sorceress: in some obscure way, often simply by means of her nature and presence, she encroaches on other people’s lives and robs them of happiness and prosperity.

It is strange, however, that although the sorceress often spent years thus appropriating the assets of others, and although many people felt robbed or deprived of something, she did not seem to grow fat from her life of crime. Here, the case of the witch is the same as that of the children substituted by the devil, the so-called changelings, mentioned in Malleus Maleficarum: however much they are fed they will never be satisfied, are always ailing and do not grow. The sorceress is obviously a human who was ‘substituted’ at the outset. She was never acknowledged as a legitimate child.

Power

“If you will be mine, I will give you the power to…” As the motivation to enter a pact, the confessions sometimes refer directly to the power granted by the acquisition of magic abilities. All magic activity practiced by the sorceress is obviously, and regardless of its purpose, the exercise of a form of power. This is particularly apparent in a common variety of witchery against people: the application of insanity, or versions of madness. “And when he entered the house he became so angry and demented that he ate and bit the earth and bit large holes in his shoes and tore off his clothes, so they had to fetch other people from the town to restrain him.”

The sorceress might also make a direct threat that she would exercise this kind of power:

“As soon as she could gain power over him, she would make him so scared that his insides would burn and he would languish.” The sorceress makes an active intervention in a person’s mind, in areas over which humans have no control. Like the witches in Macbeth, she pounces on singular passions, shakes up the demons that are already there; with brews and vapours, gesticulations and raging incantations, she befuddles the victim’s human consciousness. There are clearly people who seem particularly susceptible to sorcery – Ole Bellringer and other intensely zealous and frightened witch-hunters – and there are some who cannot be affected because they have “commended themselves too strongly to God”.

In more recent literary depictions of witches – in the work of Karen Blixen and Fay Weldon, for example – this special ability to intervene and manipulate the life of the unconscious is the focal point of the characterisation, and it is also operational in every act of sorcery regardless of whether or not it becomes manifest. At the time of the witch trials, this ability caused the greatest agitation; it was the factor that determined people’s actual fear of the sorceress. She thereby acquired – and it was the only thing she did acquire from the promises of the pact – a kind of status, a kind of power.

“Whore and sorceress”

The Danish witch trial records are not exactly full of direct references to sexuality. This has caused many scholars to conclude that the sexual aspect played no appreciable role in the contemporaneous picture of the sorceress; a conclusion presumably reached because this is an area in which it can be difficult to see the wood for the trees. It all begins with the woman’s “betrothal” to the demon she will now “serve”, or who promises to “service” her (a few of the confessions made by men state that his “boy” is a female devil): a straightforward expression of the idea, at least the latent idea, that the seed and initial stimulus of all sorcery and witchcraft lies in gender relations, in sexuality.

This basic view in itself – that a woman’s closest ally or cohabiter is a male demonic being that no one can see – puts her beyond any accepted sexual category. Does she lie with her husband or her devil? If you have a devil in the cupboard how much use do you have for a husband? Not much, apparently: “She had not lain with her husband, Peder Skrædder, for three years, but had lain with her boy, whose penis was cold as ice.” The nature of the relationship varies quite a lot, depending on the individual’s imagination and inclination. Under interrogation, Karen Gregers from Falster readily tells that the devil “in the semblance of a black dog […] for she had always so loved dogs […] should in return have all the blood that flowed from her for as long as she lived, which she gave, and he had took of her blood every month when her time came, as is women’s practice.” The sorceress’ special relationship to those aspects is further apparent from cases in which we learn that she has helped such and such a person to gain or lose his “manhood”. (Of all the forms of sorcery, this practice is the most discussed in Malleus Maleficarum.)

“And note, further, that the Canon speaks of loose lovers who, to save their mistresses from shame, use contraceptives, such as potions, or herbs that contravene nature, without any help from devils. And such penitents are to be punished as homicides. But witches who do such things by witchcraft are by law punishable by the extreme penalty […].”

(Malleus Maleficarum)

In all these respects, the confessions are in complete agreement with Malleus Maleficarum and the papal bull, both of which also open with an account of how it all begins, of humans having intercourse with incubi and succubi. The confessions also agree with the Early Church Father Augustine, who played an important role in drawing up the Church’s demonology: “All forms of witchcraft have their original cause in the abominable union between humans and demons.”

The Bishop of Zealand, Peder Palladius (1503-1560), knew exactly what it was all about:

“Why should he not dare be in cahoots with her, since a sorceress is the devil’s milkmaid, she milks him and he milks her for so long that they milk one another into the abyss of Hell. Beware their retaliation, we will speak no more of them.”

Mælkedeje (milkmaid) was a term applied to the mistresses of church ministers, so here Palladius was perhaps killing two birds with one stone.

But what does being the “devil’s milkmaid” entail? What does it mean to lie with the devil? Yes, this was exactly what the inquisitors, in much the same way as Freud later, wanted to find out: what is actually going on here?

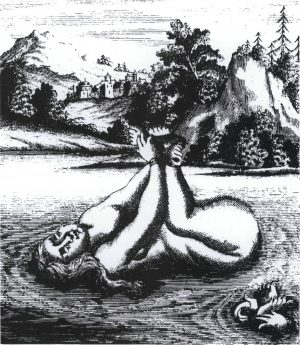

So the question was: what is happening, or what happens to female sexuality when it gets out of control, when it does not follow the beaten track? The European witch trials took a ruthless approach to finding out. The woman was not only stripped to the bone during interrogation, but her hair was subjected to a brisk blade: her pubic hair as well as the hair on her head was shaved off – every female hair, the attributes of her gender – in order to see what it concealed. In order to find the Devil’s Mark in womankind.

Sabbaths

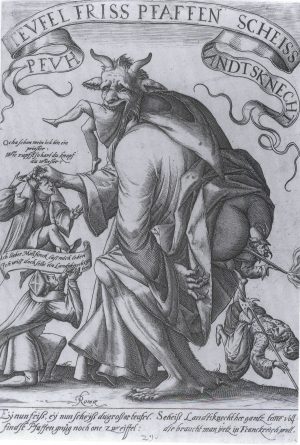

One other practice in which sorceresses indulged will here be examined a little more closely. Many confessions give accounts of gatherings of sorcerers, held on specific days of the year and week, and usually in specific localities, when the participants ate, drank, made music and danced, and engaged in worse acts. The accounts of these “parties and feasts” make it perfectly clear that they were rudimentary Sabbath gatherings, as recorded at trials elsewhere in Europe: rudimentary, but nonetheless of sufficient scope to reflect the Sabbath ‘idea’. It is rather frustrating to scrutinise engravings or read European trial records and demonological literature of the times (which is where the Sabbath was given systemised specifications). This is not due to any lack of interesting ingredients – witches flying, initiation ceremonies, dancing and feasting, the brewing of poison and ointments, and sexual orgies, including intercourse with the devil – but because it is impossible to get an impression of the reciprocal connection between the elements, their function as a description of internal or external sequences. Until, that is, it becomes apparent that the Sabbath is actually a depiction of the absence of meaning, order, and coherence. It is an exposition of the negation of a recognisable human reality: dance is danced back-to-front; music made by beating with bones and skulls is non-music; the food tastes foul and needs salt; copulation, which is either indiscriminate or with the devil, whose penis is ice-cold, apparently gives no passion or pleasure; at the initiation ceremony, the adepts do not kiss the sacred objects but rather the devil’s fetid arse, and so on.

Unlike Carnival, the Sabbath thus does not represent an inverted order designed to point up and release sexual instincts or appetites otherwise held in check – and hence a kind of purging process – it represents a perverted order. The overarching characteristics of the witches’ Sabbath, the total image that comes closest to describing the witches’ ‘community’, or life in witch-land, are: non-expression, non-humanity, and non-community. A prelude to Hell.

Beneficium

The picture of the sorceress, as painted in the confessions, is dominated – as might be expected – by the varieties of malevolent sorcery, maleficium, through which she, in fulfilling her side of the pact, has inflicted illness, misfortune and death on people and animals. In some of the confessions, either in passing or as a direct admission, the woman also mentions her activity as ‘wise woman’. Although very few were charged and sentenced exclusively for the practice of white magic, the large proportion of wise folk (approximately one third) among the accused would suggest that – at least during the period of the witch hunts – those already involved in such practice were more vulnerable to suspicion.

The women themselves, when making the confessions, often take an extremely confused position on their own healing activities. The aforementioned Karen Gregers from the Falster case (who had seemingly only ever practiced white magic), for example, lists – with something akin to professional pride – no fewer than fifty persons whom she has “helped” over the years. She nonetheless later declares that she deserves to pay with her life for her actions. Another defendant in the same case, Anna Kruese, says that her ability to heal was given to her by the devil, and she later recites a blessing that she has used against “shots”: “Our Lord Jesus was sitting at his chimney with tilted head, when the Virgin Mary walked by, the blessed mother of Christ; why are you sitting here, my dear son, with your head inclined; why should I not incline my head, I [am] shot by elves, shot by goblins, shot by gnomes and beaten by elder-tree kings, pauper kings, blue kings […] on my head and my chest, arise and walk to your sacred cross where you lost your sacred blood […] sound and healthy I do thus make you in the name of Christ.”

Given that Mary herself (yet to be effaced here by Lutheranism, try as it might) can act as the blessing giver – and, what is more, for her own son, the little mite – it can be difficult to understand why this should be a crime in someone else. Anna, however, also states that she “was willing to suffer [death] for her sins”.

In a way, this almost schizophrenic relationship to their own activities as wise women gives the most heart-rending demonstration of the extent to which, by criminalising central aspects of the women’s behaviour and activities, the trials could affect both the contemporaneous attitude to women and the self-image of the individual woman.

Whose Words?

“Anna Lourups replied that upon this confession she would die, and that she has thus received the sacrament.” Besides telling the story of a woman’s life as prescribed, the confession is, in itself, the final event of this sorceress’ life. By making a confession under oath, she swears herself out of the diabolical pact and into the baptismal pact. By so doing, however, she signs her own death warrant.

Through the tripartite structure itself (entering the demonic pact; the social consequences or manifestation: maleficium; rescinding the pact) the witch’s confession stamps sorcery as a double crime: the actual harm caused and the mental state that is the precondition for the action, heresy, the perversion or diversion of the soul, manifest in the nature of the pact. In a different framework, this twofold context has later been applied to the evaluation of every kind of crime. Here, the term “dark deeds” means quite literally that they take place in darkness, hidden, beyond cognition, where demons and non-consciousness reign. Beneath the prejudice and incompetence of the inquisitorial interrogation proceedings it is also possible to trace a rather direct and objective interest in exploring this ‘unconscious’.

As a genre, confession – and this applies to confession to a priest, words of the analysand, a guilty plea in court and the literary confession – is on the borderline between the covert and the overt. Confession gives exposure, gives a platform and a place in the community.

From an ecclesiastical perspective, the witch trials are thus a ‘mini Judgement Day’, by means of which the sorcerer becomes a human being, is ‘redeemed’. This theory of redemption is used by the Church as its ideal intention when justifying participation in the 300-year-long trial of witches/women: something was rampant, women were up to this and that – which they of course always had been; Malleus Maleficarum worked out that the abomination could be traced back to c. 1400 BC, and that it had simply become worse – and now enough was enough. All that female secretiveness, indeed the insufferable mystery of woman herself, was now going to be exposed – or, as Sprenger and Institoris report: “No one does more harm to the Catholic Faith than midwives.” The woman had to be brought inside the fold; she had to be put into words. She had to be redeemed, dead or alive.

The question is, of course: to what kind of redemption were the women subjected by means of the trials, and through whose words were they redeemed?

As suggested in the above, it would seem that confession fulfilled an objective for some of the accused by placing them at the centre of the sorceress narrative. Even though they were given the opportunity to deny all or parts of a confession, several women chose to swear the most profound of oaths that what they had said was the truth, word for word. There are also examples where the mood of the trial shifts at the moment the woman starts to confess. Fear and hatred on both sides might be replaced by an almost jovial atmosphere in which details of sorcery or the devil’s physiognomy came under discussion. In such situations, the accused is experiencing a form of negative reconciliation with the town or village community, from which she has been ostracised for a shorter or longer period of time. Through confession she was again, or perhaps for the first time, accepted. As a sinner, of course, but repentant. She was on the inside. She had been recognised.

By means of this process, these women might also have been rendered ‘recognisable’ to themselves. If their actual life had hitherto comprised an enormity of anonymous suffering, violation and privation, then through confession it achieved a kind of coherence and meaning, interpretation – and significance.

Under the circumstances in which she found herself, no one can blame the accused for giving up and making a confession. However, the interpretation or classification of the woman reached through the trials clearly came at a price. The confessional situation, which collated or ‘discoursed’ a popular and an ecclesiastical image of the witch, built up an image of women in general that was to have consequences both during and after the trials, as a factor in the disciplining of the female sex, not least the members of that sex who ‘betrothed’ themselves to literature.

Translated by Gaye Kynoch