Sonja Åkesson’s (1926–1977) best known poem is “Självbiografi” (“Autobiography”) from Husfrid (1963; Domestic Peace). It is a pastiche of another poem, “Autobiography” by the American beat poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti. Both poems are approximately 300 lines long. Sonja Åkesson’s pastiche can be interpreted as countering the American original. The woman in the Swedish poem is passive and depressed, uneducated and culturally ignorant, but interested in people. The man in Ferlinghetti’s poem is a globetrotter, on first name terms with the cultural heritage, who believes in his role as a poet and compares himself to Icarus in flight. “I had no wings / but a well developed hump”, Åkesson’s woman replies.

I leaped into the early dusk

and would stretch my hand through the sky

but hurried back home

not to burn the potatoes.

I see a resemblance between me

and potatoes.

At the least basement light these groping stalks.

But beware of bruising.

Beware of cold.

“Självbiografi” has mistakenly been perceived as Åkesson’s own autobiography. In most of her poems, the same voice is heard: the voice of an uneducated woman, a lonely being, victim of a commercialised society and a crippling female role. It functions as a stock character. The same role recurred in the many texts she wrote for the theatre during the 1960s, when she was active in independent theatre companies.

Sonja Åkesson’s best known woman’s poem is “Äktenskapsfrågan I” (Marital Question I), often named for a line from the first stanza: “Be White Man’s slave”, from Husfrid (1963; Domestic Peace):

Wife ladle sauce.

Wife cook dirt.

Wife manage dregs.

Be White Man’s slave.

About the New Simplicity

Åkesson made her debut in 1957 with Situationer (Situations) and published one other collection during the 1950s. In the early works her writing style wavered between the refined metaphors of nature- and village-poetry and the grotesques depicting human nature that she would later develop.

At the threshold of the new decade, in August 1960, she co-authored the manifesto “Front mot formens tyranni” (Front Against the Tyranny of Form). This manifesto caused cultural debate and was an important step out of the Modernism of the 1950s towards the Realism of the 1960s. The other manifesto authors were P. C. Jersild, Kai Henmark, and Sonja Åkesson’s husband Bo Holmberg. They sought a stronger engagement. But when, later in the debate, the various manifesto authors attempted to specify this engagement, they turned out to have differing opinions of the intent. Jersild and Holmberg intended a social commitment, while Åkesson and Henmark rather intended something in the style, a closer approach to the motif, a means of writing that seized its readers.

The first years of the 1960s introduced two different poetic schools, New Simplicity and Concretism. The first wanted to leave behind the complex metaphors of modernism and the existentialist themes. Poetry had to be about everyday matters and be immediately accessible. The Concretists experimented with the sounds and imagery of the language. But followers of New Simplicity also experimented with language. Not for nothing was the movement’s manifesto – written by Göran Palm – called “Experiment i enkelhet” (Experiment in Simplicity).

New Simplicity suited the women with an interest in everyday life and everyday speech. Sonja Åkesson found her own special tone within the frame of the new simple aesthetic through inspiration from Concretism. Husfrid is one of the great collections of poetry from the first years of the 1960s. For Sonja Åkesson, it was a major breakthrough with the public. Until her last collection and her death in 1977, she developed and deepened the style of writing she reached during the first half of the 1960s.

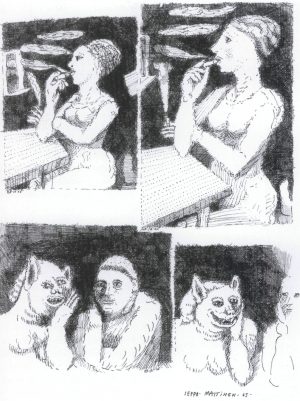

Quite possibly, the most conspicuous trait in Sonja Åkesson’s works is her grotesque irony. Irony presupposes a basic ambiguity. One hears her poems scratch the surface, but underneath all the irony the reader meets the vulnerable woman trapped in her objectified body, in commercialised society, and in her atrophied gender role, locked away in terror of violence and death.

Åsa Nelvin’s (1951–1981) works are close to Sonja Åkesson’s in her pessimism and her grotesque depiction of mankind. Åsa Nelvin committed suicide while still young. She wrote two children’s books, but even her other books are marked by nightmare-like tales. The novels describe a disintegrating psyche. The cycle of poems Gattet (1981; The Hole), published the same year as she died, describes how a seven-year old girl experiences a summer visit to the family farm in Scania. This is the city child who is horrified and disgusted to see excrement in the corners and the bloody remains of slaughter on the dinner table.

By speaking in everyday language about everyday matters, the new simple style got rid of the old high-modernist means of exposing the soul. Sonja Åkesson, specifically, reached the furthest within the frame of New Simplicity. It was a woman who delivered the strongest input for poetry to leave modernism, just as Edith Södergran had been a pioneer in the introduction of Swedish-language modernism.

Åkesson banked on everyday speech as her poetic language. It is a language with many female traits, according to some investigations into women’s group language. Women tend to use exaggerating adjectives such as ‘wonderful’ or ‘lovely’. Women replace substantives with pronouns and use coordinated clauses, while men use subordinated clauses. Women often ask, and display ignorance (“I have no idea”). Women speak more fluently in private and less in public. This manner of women’s speech looks like a strategy of submission.

These are the traits found in Sonja Åkesson’s poems. And it is very much an innovation. This language has not previously existed in poetry:

Imagine if you could reply to me!

No ugh no.

Never mind what I’m saying.

Such a lot of nonsense

it turns in the throat.

Showing the World

Sonja Åkesson’s dominating style is a raw, narrating realism. The characters passing through her poems deliver a lively narrative about other people – for instance Ullagull in “Skäggiga damen” (“The Bearded Lady”) or the twenty-year old woman in “Sommarbild” (“Summer Image”), Aina with the protruding teeth or the scary-nasty Post-Agnes.

But the satire of society is just as important a genre for Sonja Åkesson as the character portraits. One gets inside the countryside of Gotland: “He who takes a bottle of plonk / is the Drunkard. / She who gives him a cigarette / is the Park Tippler. / He who peeks from behind the hedge / is the Peekaboo […].” From “Samhälle” (“Society”) in Dödens ungar (1973; Kids of Death).

Sonja Åkesson identified with the weak of society. She was an uneducated woman from the countryside and troubled with a fragile psyche. In Sonja Åkesson’s work, the oppression of women is shown in various denigrating variations.

But Sonja Åkesson also wrote purely political poems. In “Sandvikens Jernverk” (“The Sandviken Ironworks”) from Ljuva sextital (1970; Lovely Sixties), she interviews workers and managers, describes the production processes, and composes a depressing song about the single mother who sits in her crane and attempts to gather enough to support her family against all odds.

Sonja Åkesson’s strongest political poem is a whole book, the collage work Pris (1968; Price). The book is constructed from cutouts from the press and a warehouse catalogue. It is not a conventional poetry collection but ready-made after Duchamp’s example. In Pris, Åkesson seeks out the language of oppression. One discovers the manipulative power of commercial language.

In Pris (Price) Sonja Åkesson cuts together lines from ladies’ magazines with lines from men’s magazines, and lets it all explode:

SHE: It is love that makes things beautiful

HE: If you try anything you will feel this!

SHE: Love – the inspiration of life

HE: Time for violence. Sexy in colour.

The book ends with the scary poem “Skummat” (Frothy), a listing of some normal newspaper headlines: “Thrashed with a sandbag Our only hope Treated like animals / War on the backburner 8000 lost The knife and the shirt […]”

Showing the Body

But Sonja Åkesson did not stay within the framework of raw realism. The grotesque perspective on life and people influences her poetry rather a lot. In the poems from the 1950s, the grotesques dominate the characterisations. The women’s bodies are described with a mixture of burning compassion and disgust. The subject may be women’s poor relationships with their own bodies, inadequacy in meeting the demand to be pretty, fresh, and young: “The mirror is narrow, but she sees / both in the brushwood and marsh / through the steel-rimmed. / (Cheeks: red apples, / wrinkled by frost. / Mildewed underneath the sacking. / The rye dough underneath the shift.)” Occasionally the body is described as an object, or as a slab of meat: “Delicacies on Spit / The Gourmand’s Lucullus Thighs / Madame’s Exquisite Kidneys / Mamma’s Summer Dream / Cheerful West Coast Pot / Negro in Shirt”.

The poem quoted lists ninety-six different recipes with authentic names. It is a collection of recipes that can stick in anyone’s throat. Apart from the sexual and political allusions, the reader also gets a disagreeable sense of participating in a cannibal’s meal.

This way of listing expressions and then letting them head into the absurd is a technique Sonja Åkesson invented. With her frenzied repetitions and two beats per line, it occasionally turns into a witches’ dance with polka rhythm, which in Swedish prosody is called nystevdikt.

Occasionally, the grotesque behaves like a nightmarish surrealism:

In India-land the lepers live.

They carry neither cheeks nor bloom.

In their heavy eye pearls live

little drooping violets, little dogs.

Is it a 1960s committed to Third World issues we hear in this poem, or dread from an inner world? This is part of the collection of songs Slagelängor (1969; Battle Noises), for which Gunnar Edander composed melodies to a number of Åkesson-poems, “the twenty most easily sung song-bites outside the usual Swedish top of the pops”. Several of the songs originated from Sonja Åkesson’s collaboration with the independent theatre groups, who loved her songs and monologues.

But the poems that most resemble surrealism are the so-called together-poems, which she literally concocted with her husband Jarl Hammarberg. And precisely this co-writing dissolves the first precondition of surrealism – to be a report from the unknown depths of the soul. This does not depict the soul under four eyes, but the concocted poems borrow the fluency of surrealism and its violent imagery.

The two co-writers published three books, Strålande dikter – Nej så fan heller (1967; Radiant Poems – Hell No Way), the radioplay Kändis (1969; Celebrity), and Hå! vi är på väg (1972; Ha! We Are on Our Way). These books, too, are innovative, a new genre. They settled on a structure, for instance question-answer, and then filled in every second line. In Strålande dikter, she is responsible for the capital letters, the husband for the lower case letters – a case of equality within the marriage?

Rather rouse than delouse

Rather sage than rage

Rather mend than bend

Rather back than clack

We’re hanging in there we’re hanging in there

Rather seedy than greedy

Rather rush than bolt and loseRather feed than speed

Rather admitted to a madhouse than belittled

The last sample illustrates how the sound qualities of the words are allowed to control the meaning. The sound play of the concretists sometimes slides into disconnected flow.

Body and Death

In Sonja Åkesson’s poems, humans primarily consist of their bodies. The railroad guard’s girl had no soul, we are reassured in the first book, and in the last, twenty years later, the question comes: “The soul, wossat?” One might say that Sonja Åkesson’s poetic world is rooted in a secular conviction. Bodies are objectified and made into things. She describes how it is to live in a body with which to act, that is even interacted with by business.

The body is subjected to violence and threat, disease and death, it is treated like an object, often in dissolution, it is threatened by death. The old, facing decomposition, are depicted with tenderness and irony. Occasionally the body is under threat of being consumed by the nearest and dearest – cannibalism as a way of living together is one of Sonja Åkesson’s recurring suggestions: “I boil you / cook you / grill you / make lung hash / blood-pudding / liver pies”.

The characters in Sonja Åkesson’s poems are reduced. The poetic speaker, the set character, denies itself, not to say degrades itself. The animal symbols derobe the characters of all grandiose claims. The reductions can be said to belong to the repression of women, the habit of making oneself small and insignificant.

Apart from her poetry Sonja Åkesson has published a novel, Skvallerspegel (1960; Window Mirror), and a collection of short stories, Efter balen (1962; After the Ball). Several of the books from the 1960s mix poems with short stories, for instance Jag bor i Sverige (1966; I Live in Sweden).

Marriage is described as a providing arrangement with captive wives for men with “looks full of dead meat”. Mankind is sterile. They lack children, and even if they have them, the children are lost.

Sonja Åkesson recreated the obsolete genre of epic verse on the basis of haiku. Sagan om Siv (The Tale of Siv) was published in 1974. 122 stanzas, each consisting of three lines and seventeen syllables, tell a rather depressing love story. Being inspired by the Japanese haiku allows for an abnormally high level of stressed syllables. The verses become progressively heavier as the depression of the main character increases. Thus, the action is illustrated through rhythm.

Death and fear of death are always present in Sonja Åkesson’s poems. The mother’s fear at the child’s sickbed is a recurring motif. Twice – in “Bårhuset” (The Morgue) from Husfrid and in “Farbror Nordgren” (Uncle Nordgren) in Hästens öga (1977; The Eye of the Horse) – a death symbol appears, a sort of Grim Reaper. But it takes the female form. Moreover, these women with scythes also appear simultaneously as victims and executioners, an ambivalence that probably belongs with the acknowledgement of guilt that runs through Sonja Åkesson’s work.

Fuck on.

She lies there thinking about

the spider’s web in the ceiling

the lamp shade that has gone yellow from smoke

the child waking in another house

in another town

in another bed

relating its nightmares

to she doesn’t know whom.

He releases it

Hästens öga (1977; The Eye of the Horse)

Translated by Marthe Seiden