– ON NORDIC WOMEN’S LITERATURE IN THE FIRST DECADES OF THE 21ST CENTURY

By Anne-Marie Mai

Ideas and notions concerning gender have become some of the most important literary themes of the early 21st century. Female and male authors have enthusiastically thrown themselves into a bona fide discovery of the possibilities offered by social gender and biological sex in terms of new ways of life, self-esteem, self-knowledge, and insights in a global world. Gender themes are employed in investigations of ideas and notions concerning the human condition, grieving, loss, attachments to the past, desire, and madness. A range of writers appear to be unconcerned with traditional notions of heterosexuality, homosexuality, and transgender issues, all the while attempting to outline a new sense of responsibility towards fellow human beings, children, and life on earth by questioning what gender – socially and existentially – may be and become.

Various Nordic women and men have achieved literary breakthroughs on a global scale thanks to their innovative stories about gender and humanity. Sofi Oksanen (b. 1977), Sara Stridsberg (b. 1972), Monica Fagerholm (b. 1961), and Naja Marie Aidt (b. 1963) as well as Karl Ove Knausgaard (b. 1968), Kim Leine (b. 1961), and Einar Màr Gudmundsson (b. 1954) all display a literary interest in rereadings of personal and national histories, facing the present, and investigating the transformations of gender and existence.

Similarly, among younger Nordic writers, Greenlandic Niviaq Korneliussen’s (b. 1990) debut, HOMO sapienne (2014), depicts the intersection of gender and ethnicity in the life of a young women and Danish Bjørn Rasmussen’s (b. 1983) collection of poetry, Ming (2016), is a rendering of how a man’s new existential and gendered courage is accompanied by sorrow, anxiety, desire, and emotional turmoil. Gender is in flux in new Nordic literature and it is thus placed at the very forefront of literary debates.

In the article, Forfatteraben (2016; The Monkey Writer), Hanne Højgaard Viemose (b. 1977), one of the newcomers to Nordic literature during the 2010s, deals with gender roles in literature and critically questions the concept of ‘women’s literature’. She outlines the paradox of, on the one hand, writing about female bodily experiences and, on the other hand, not considering oneself a ‘female writer’:

“I don’t really consider myself a female writer. On the one hand, I have, in my latest novel, Mado, written extensively about a woman’s experiences with pregnancy and childbirth, abortions, dieting, dealing with one’s body after childbirths, being a mother, being a single mother of small children, being horny, menstruating, lactating, masturbating with bare hands.”

She recounts how schoolchildren reading excerpts from her debut novel, Hannah (2011), have interpreted the protagonist as a young man and as a young woman. Gender also constitutes a literary gaze with which one may challenge oneself and one’s readers.

On the concept of women’s literature, she says:

“When somebody labels me as a ‘female writer’ or speaks about ‘women’s literature’, I cannot help thinking that I must be some kind of monkey. Or the ‘savage’, encountered by an anthropologist in the jungle two hundred years ago, who was subsequently discovered as being able to speak, thus surprising and delighting the anthropologist who felt compelled to write articles about this fascinating phenomenon. Many years later, someone had the brilliant idea to ask the monkey/woman/savage to write about their experience of being a monkey/woman/savage.”

Hanne Højgaard Viemose’s assertion, that the history of literature has had its share of patriarchal anthropologists who deselected women from the canons of literature, thus rendering them the ‘monkeys’ of literature, by the deployment of the concept of female writers, rings true. During the 18th century, gender simply became the most decisive factor in determining the survival of a literary oeuvre and its canonisation in the national histories of literature.

20th century literary scholarship has thus been faced by the mammoth task of rediscovering the numerous great and forgotten female writers of the past. The present work, Nordic Women’s Literature, represents the completion of a scholarly endeavour initiated during the 1970s in the Nordic countries. Here, the concept of women’s literature was employed as a search term in order to describe everything, which had been excluded by the male dominated literary culture.

During this period, ‘women’s literature’ became a catchphrase for a break with reigning literary culture, as women demolished the niche position they had previously been consigned to. A whole host of female writers insisted upon the existence of a new literary diversity and made room for literature in feminist consciousness-raising groups, at women’s festivals, and in experimental performance art.

In this break with tradition, dominant tropes of culture were questioned and the concept of gender presented a point of entry for new stories of life in the Nordic welfare states. The break with notions of gender in Nordic literature from the beginning of the 21st century is rooted in developments of the late 1960s and early 1970s. The main protagonists of this break during the mid-1960s are both male and female writers, e.g. Danish Dan Turèll (b. 1946), Norwegian Eldrid Lunden (b. 1940), and Swedish Per Olov Enqvist (b. 1934). The female writers, however, introduced – in terms of style and themes – a new agenda for the depiction of gender with wide-ranging consequences.

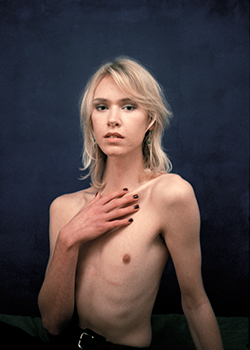

Lotte Fløe Christensen. 2014

The concept of women’s literature is still a useful discursive tool to have at hand. When asked about its justification, the Swedish writer, Mara Lee (b. 1973), responded:

“It would be very easy to reply, ‘No’, to the question of whether one may speak of female writers. However, I prefer to rephrase the question: ‘When may one speak of female writers?’ I think its use is justified at times. We should not merely relinquish this option because it is often important to assert one’s gender. But then, at times, things are also haphazardly lumped together under the guise of this somewhat random concept.”

The Norwegian writer, Linn Ullmann (b. 1966) testifies to the continued existence of the old story of women and monkeys depicted by Hanne Højgaard Viemose. Ullmann relates the story of how, when invited to a book fair in France, she found herself and a number of other female writers excluded from the main event:

“- Once, I was invited to a festival in Paris with many other writers. I then discovered that I and the other female writers would all be lumped together and interviewed under a common title, Eve’s Corner. I could not help myself: ‘This may be a somewhat naïve question, however, what exactly is Eve’s Corner? None of us are called Eve’, I asked the organiser. This conversation occurred by e-mail but nevertheless, I imagine the answer in a pronounced French accent: ‘Ah, but you zee, you are ze Eve, you are ze woman!’ Well, ok then, where is Adam’s Corner?’, I replied.”

Since the 1970s, the concept of women’s literature has been the title of and a core concept of a critical literary resistance against precisely these kinds of degrading declassifications and unfair exclusions of female writers.

DISTRESS SIGNALS AND NEW CATALOGUES

In Norway, Bjørg Vik (b. 1935) subjected the theme of women’s lives in the welfare state to a critical reading in her collection of short stories, Nødrop fra en mjuk sofa (1966; Distress Signal from a Soft Sofa). Women, at the heart of the comprehensive conflict between the traditional and new gender roles, are particularly hard hit by the superficiality and boredom of life in the emerging welfare states. In Denmark, Charlotte Strandgaard’s (b. 1943) debut collection of poetry, Katalog (1965; Catalogue) presents an uncommonly level-headed portrayal of a young woman’s experiences with relationships, pregnancy, and childbirth. The description of motherhood is bodily and concrete and completely devoid of the tendentiously florid mythologisings of 20th-century modernism and realism. In Sweden, Kerstin Ekman’s (b. 1933) oeuvre undergoes a decisive about-turn with the publication of the novel, Pukehornet (1967; The Devil’s Horn). Here, Ekman, who had previously only written crime fiction, deals explicitly with the writer’s opportunity for experimentation in her presentation of stories and human destinies. In Pukehornet, the portrayals of a failed editor and an old, odd woman are a testament to how literature may open up new avenues of diverse gendered interpretations. By virtue of a double gaze, which demonstrates how the male and female view on events and history may differ considerably, the reader – rather than the writer – assumes the position of authority in the story.

During the 1970s, this break became a large-scale phenomenon involving writers such as Märta Tikkanen (b. 1935, FIN/SWE), Suzanne Brøgger (b. 1944, DK), Liv Køltzow (b. 1945, NOR), Kerstin Thorvall (1925-2010, SWE), and Auður Haralds (b. 1947, ICE). It becomes increasingly clear that women’s contribution to this literature of change consists in genre experimentation and a hitherto unheard of and overt use of biographical material. Male and female writers share an experimentation with minimalism, beat poetry, documentarism, magical realism, neorealism, and modernism. However, by entering the private sphere, which has traditionally cloaked writers, women were the first to succesfully break the biographical taboos of fiction.

THE PRIVATE IS POLITICAL

“The private is political” became one of the greatest rallying cries of the Nordic feminists. It became the motto of the consciousness-raising groups where women shared their experiences with sexuality, relationships and cohabitation, children, and work. After women’s experiences had been rendered invisible and invalid by the ‘privatisation’ of significant swathes of women’s lives it was time to dismantle private taboos and share one’s experiences. In order to transform gender roles and liberate women, is was essential that what had traditionally appertained to the private sphere was now considered as possible shared experiences, which had to be brought into the open. In her ground-breaking collection of essays, Fri os fra kærligheden (1973; Deliver Us From Love, 1973), the Danish writer, Suzanne Brøgger, brandishing her very own banner of gender politics during the heated 1970s debate on confessional literature and privacy, declared the abolition of privacy as the ultimate goal.

“I believe our private lives are of such importance that they must and ought to be rendered public. No one can feign indifference to the lives of others unless one has fallen into a state of complete human decline.”

Petra Noppari.2015.

Several male literary scholars were critical of the emerging biographism. The women’s books were too private, too caught up in their own personal history, they were said to be essentially lacking in artistic distance and process. The Swedish writer, Kerstin Thorvall (1925-2010), was chastised as the originator of so-called confessional literature due to her novel, Det mest förbjudna (1976; The Most Forbidden), while Danish writer Vita Andersen (b. 1942) was reproached for being too private in her collection of poetry, Tryghedsnarkomaner (1977; Comfort Addicts). This critique has been perpetuated – decade by decade – long after Nordic literature has been struck by another wave of biography and autofiction. Many of the books written by female authors contest the seemingly agreed-upon artistic ideal of transforming personal and private material into a general and gender-neutral form. Modernist literary criticism considered Vita Andersen’s poetry as “private beyond all perspective”, as expressed by critic and writer, Jørgen Gustava Brandt, in the essay, “A som i Vita” (1981; A Is for Vita).

However, Nordic women’s literature was a large-scale testament to the end of an era of a literary culture overshadowed by ‘large’ artistic personalities who entirely converted their secluded private capital into universal art. Women had scarcely broken the taboo of privacy before men joined in and rendered biographical material an overt literary source, an aesthetic challenge, and a performative gesture in heterogeneous literary forms between fiction and biography.

Confessional literature, autofiction, and later performative biographism became the terms indicating the many hybrid forms of biography, fact, and fiction engaged in by Nordic writers. And Vita Andersen witnessed a veritable renaissance among several young writers. In 2013, her two first books were republished by poet Olga Ravn, who penned a brilliant preface to Andersen’s books – now considered milestones in literature.

These new hybrid forms of literature – between biography, fact, and fiction – shattered, in the words of Poul Behrendt and Mads Bunch, the “glass façade” of modernism and allowed for new readings, including the study of the relationship between the empirical author of a literary work and the text itself. (Poul Behrendt & Mads Bunch: “Autofiktion har knust modernismens facade”, Politiken, 28.4.2015)

Additionally, it became clear that the empirical author, too, could not easily be drawn and delimited as a figure. E.g. the Danish writer, Claus Beck-Nielsen, whose various transformations have challenged the concept of the empirical author, i.e. the figure, “Madame Nielsen”, whose identity as a kind of reborn Karen Blixen is employed in the novel, Invasionen. En fremmed i flygtningestrømmen (2016; The Invasion. A Stranger Among the Flux of Refugees), in order to pursue the contemporary grand themes of migration and European identity. Danish writer Christina Hagen similarly questioned the figure of the empirical author when she allowed herself to be represented in television interviews by a young, beautiful female student of literature in order to hammer home the point that the media are primarily interested in female writers, who look great in photos. Protesting against media stereotypes of women’s role in literature, she made her position clear in an article in the newspaper, Politiken, entitled “Man skal ligne en kneppedukke for at blive hørt”, or In Order to Be Heard, One Has to Look Like a Blow-Up Doll (Politiken, 23.8.2014).

A similar protest was seen, when one of the pioneers of women’s literature, Swedish Kerstin Ekman, published her final novel to date, the satirical Grand final i skojarbranchen (2011; The Grand Finale of the Dodger’s Business). Here, the beautiful and talented writer, Lillemor, harbouring all the right views and boasting a flair for the public life of an author, is threatened to be unmasked by her alter ego, the fat and rebellious Babba, who is the actual writer of Lillemor’s oeuvre. This is an autofictional novel about autofiction, a story where Ekman unveils contemporary stereotypical mediations of the writer in literary culture and concomitantly posits the individual reader as an authority perfectly capable of forming their own opinions. Despite the numerous mediations of the author, autofiction is able to directly turn the cards of interpretation into the hands of he reader.

THE TENDENCIES OF TWO DECADES’ WORTH OF LITERATURE

The Swedish writer, Mara Lee published her novel, Future Perfect, in 2014. It is a complex and vast novel about the tempestuous and beautiful seamstress, Dora, her two sons, Lex and Trip, and the mysterious girl, Chandra, with whom they all fall in love. The title of the novel, the tense form future perfect, suggest how fragments of past and present notions of madness, sexuality, and otherness flutter about the characters and render their futures strangely final and shut. Dora, who makes clothes for people with physical disabilities, becomes the owner of the so-called ‘Green Book’, L’Amovibla: The Art of Sewing and Survival, about a mysterious set of clothes, the origins of which remain forgotten by history, which may be an enigmatic erotic symbol of liberation. In the end, Chandra continues Dora’s project by apprenticing as a seamstress, yet the novel’s ingenious turn of events alludes to the challenges of disengaging from culture’s web of meaning, thought, and prejudices.

Mara Lee’s modernist narrative is an example of the diversity of literary forms of expression employed by Nordic writers in their attempts to express through art the linguistic and bodily norms of Nordic culture, which excludes behaviour and thoughts deviating from the gendered and ethnic norms of society. While male and female writers have dealt with these topics and themes, during the first years of the new millennium, women, in particular, have lent a strong voice to these themes, i.e. Korean-Born Maja Lee Langvad (b. 1980), who was adopted in Denmark, and Athena Farrokhzad (b. 1983), a Swedish poet of Iranian roots.

The artistic forms employed by female writers during recent decades are often experimental, blending various genres and art forms, though the high modernism of American and European women’s literature – from Virginia Woolf (1882-1941) and Edith Södergran (1892-1923) to Ingeborg Bachmann (1926-1973) and Joyce Carol Oates (1938) – serves as a groundwork.

Concurrently with the experimental, artistic exploration of norms and values, in contemporary women’s literature, we also note the re-emergence of the grand old themes of Nordic women’s literature.

Motherhood, romantic relationships, and history are classic themes of women’s literature, however the changing times and the construction of the Nordic welfare states and their subsequent transformation during the first decade of the 21st century has renewed and changed the themes. The Danish writer, Kirsten Thorup (b. 1942), whose debut, Indeni – Udenfor (Inside – Outside) hails back to 1967, has often examined the theme of motherhood. However, in her novel, Erindring om kærlighed (2016; Recollection of Love), the portrayal of the problems of motherhood is interwoven with a depiction of the dark side of the welfare state. Thorup’s protagonist, Tara, is struggling to care for her daughter, Siri, under socially and psychologically challenging circumstances. Tara finds it difficult to understand the needs of Siri and she is ashamed of her incapability to do so, while Siri, on the other hand, refuses to accept maternal love and insists on the independence forced upon her due to her mother’s inability to cope with life with Siri. The complications of the mother-daughter relationship turns into an allegory of the welfare state, which, in principle, strives to do good by its citizens yet is often incapable and possessive. The novel is permeated by a vision of how the forces of good of motherhood could possibly become more influential politically and ethically. The ending of the novel sees Siri apply the theme of motherhood in a vast performance work of art in which she states her hopes for a better future.

Eeva Hannula. 2014.

The ambivalence of mothers vis-à-vis the new-born child is powerfully executed in several works published during the first decade of the 21st century. Danish writer Maja Lucas’ (b. 1978) textual work, Mor. En historie om blodet (2016; Mother. A story of the Blood), depicts in pared back prose how a mother is worn out from exhaustion and by the taboos concerning the feelings of insecurity and negativity. The ambivalence felt towards a small child may still create a sense of guilt and shame in women/mothers who have been force-fed the myth of the self-sacrificing Madonna-mother. Lucas’ book demonstrates that the female body does not always constitute an inexhaustible reservoir of self-sacrificing, unequivocal love. Norwegian Benedicte Meyer Kroneberg (b. 1972) portrays the mother figure from the perspectives of the adult daughter and the child in the novel, Ingen skal høre hvor stille det er (2010; So No One Can Hear the Silence). The mother, categorised as mentally ill in the world of adults, is, in the eyes of the child, a wild “crow” with whom the child shares its secrets, a quiet, depressive “bird of the night”, and the calm “mummy”. However, the child remains first and foremost loyal to these different versions of “mother”, a loyalty which leads the adult daughter to confront her father with the repressed truth concerning her mother’s suicide. The acute gaze of the story reveals the expectations and excuses the various members of the family find themselves wrapped up in.

One may ask, whether there are any new additions to the theme of mothers, fathers, and daughters in the literature of the first decade of the millennium. One could very well reply that motherhood and fatherhood are subjected to the scrutiny of a revealing Nordic gaze and that life in the Nordic welfare states appears to posit women and men alone in the world, isolated from one another, even when living in close relationships as parents and as children. Danish writer Naja Marie Aidt’s internationally acclaimed collection of short stories, Bavian (2006; Baboon, 2014) thus depicts the awkwardness, insecurities, anxiety, aggression, and cruelty that may define close relationships. Several characters are just a single line or a small gesture from expressing a boundless contempt for each other. Christina Hesselholdt’s (b. 1962) series of novels about Camilla, the first of which, Camilla and the Horse, was published in 2008, develops the important theme of loneliness, while Norwegian Linn Ullmann’s novel, De urolige (2015; The Uneasy), lends a particular force to the theme of absence and loneliness by describing her personal relationships to her famous parents, Ingmar Bergmann and Liv Ullmann. Here, the theme of loneliness is associated with the theme of the artist and the novel makes an existential point in arguing that the father, mother, and daughter share a strong longing for close relationships, mastering the narrative, and harnessing its forces in their individual interpretations of self. Hence, the novel is also a story about the struggle to master the narrative and the interpretations of self.

Historical themes have played an important role in 20th century Nordic literature and contemporary literature of the new millennium. Female writers’ contribution to the historical novel comes in the form of stories about forgotten and disregarded lives of women, e.g. Finnish writer Rakel Liehu’s (b. 1939) novel, Helene (2003), about the artist, Helene Schjerfbeck, as well as by framing stories historically in order to underscore and shed light on existential themes, e.g. Danish Ida Jessen’s (b. 1964) novel, En ny tid (2015; A New Era), and recent works by Finnish-Swedish writer, Ulla-Lena Lundberg (b. 1947). In 2012, Ulla-Lena Lundberg carried forward a theme from her novel, Marsipansoldaten (2001; Marzipan Soldier), about the 1939-1940 Finnish-Russian Winter War, by publishing the novel Is (2012; Ice) about life in the aftermath of World War II in the archipelago of the Åland Islands. The novel excels in its cognisant depiction of the fast-approaching end of the islanders’ lives in unison with the surrounding nature. However, Is is not your run-of-the-mill story of the decay of social life on a periphery far removed from the centres of finance and culture. Rather, it is a quiet depiction of the existential and emotional conditions in a local community where everyone is depending on one another, on nature, and on the spiritual powers, “already ancient when Jesus was young” in the words of one of the islanders. While there is a contrast between the islanders and the newly arrived family of the pastor, the novel maintains solidarity with the – mutually exclusive – values of both parties. The novel is about the love between the pastor and his wife, but it is also a declaration of love devoted to a particular geographical place and a specific slice of Nordic nature.

Alba Giertz, 2015.

The historical stories often deal with themes related to World War II, however the 1968 student movement, the women’s movement, and the new artistic circles are similarly narrated with either the individual or the family at the centre of the story. The family sagas of Danish writer Anna Lise Marstrand-Jørgensen (b. 1971) and Katrine Marie Guldager (b. 1966) depict the emergence of new forms of women’s lives and the high price and dear consequences of the women’s movement. This is a case of a younger generation of female writers facing old and new womens’ lives without a trace of sentimentality.

Love, relationships, and conflicts between the sexes take centre stage in this literature. In Sweden, Lena Andersson’s (b. 1970) novel, Egenmäktigt förfarende – en roman om kärlek (2013; Wilful Disregard – A Novel About Love, 2015), inaugurated a heated debate concerning the so-called ‘Man of Culture’. Andersson’s novel is about the gifted author, Esther, who falls for such a Man of Culture, the charming artist, Hugo Rask. She is, by far, much more interested in him than he is in her, and her personal independence is destroyed. Thus, Esther’s infatuation becomes increasingly unhappy and stalker-like. The relationship between Esther and Hugo may be understood as an allegory of the power structures on the Nordic culture scene. Men of Culture, such as Hugo, seduce and eroticise while concurrently wielding a concrete power, which leads to the supremacy of their ideas. While the literature of the 1970s debated the ‘Inhibited Man’ who was unable to express his emotions, literary debates of the noughties centred on the re-emergence of old patterns of repression and structures of power in the fashionable and flourishing Nordic cultural circles despite the presence of numerous female writers. The debate reached its zenith when Swedish literary scholar and editor of Nordisk Kvindelitteraturhistorie (History of Nordic Women’s Literature), Ebba Witt-Brattström (b. 1953) published a collection of essays, Kulturmannen och andre texter (2016; On Culture Man and Other Writings) and her literary debut, Århundradets kärlekskrig (2016; The Love War of the Century). Based on her own life, in particular her marriage to Horace Engdahl, a leading member of the Swedish Academy, she critiques the pervasive male dominance in personal relationships and in the sphere of culture. As suggested by the title, Witt-Brattström’s oeuvre alludes to Märta Tikkanen’s (b. 1935) 1970s classic, Århundradets kärlekssaga (1978; The Love Story of the Century, 1984) as a reminder that the break with literary culture heralded in the 1970s continues to our day.

*

The fourteen articles included in this update of Nordic Women’s Literature outlines the many new voices and themes which have come to light since the 1998 publication of the first of five volumes of the print version. The articles expound on new themes and genres from femi-crime novels to the great narrators and splendid poets of contemporary Nordic women’s literature. Hybrid genres are also included here. The articles have a primarily inter-Nordic perspective and demonstrate how the new women of literature have contributed to the dismantling of gender stereotypes and used literature as a field for experimentation. Unfortunately, there is not sufficient room to include all important and notable authors. However, it is our hope that a door may have been opened, allowing readers to continue their own discoveries of the multiplicity that is Nordic women’s literature.

FICTION

- Naja Marie Aidt, Bavian. Gyldendal, 2006

- Vita Andersen, Tryghedsnarkomaner. Gyldendal, 1977

- Lena Andersson, Egenmäktigt förfarande – en roman om kärlek. Natur & Kultur, 2013. Wilful Disregard – A Novel About Love. Picador, 2015.

- Suzanne Brøgger, Fri os fra kærligheden. Gyldendal, 1973. Deliver Us From Love. Quartet Books, 1973

- Kerstin Ekman, Pukehornet. Albert Bonniers förlag, 1967

- Kerstin Ekman, Grand final i skojarbranschen. Albert Bonniers Förlag, 2011

- Christina Hesselholdt, Camilla and the Horse. Rosinante, 2008

- Ida Jessen, En ny tid. Gyldendal, 2015

- Niviaq Korneliussen, HOMO Sapienne. Milik, 2014

- Benedicte Meyer Kroneberg, Ingen skal høre hvor stille det er. Cappelen Damm, 2010

- Mara Lee, Future Perfect. Albert Bonniers förlag, 2014

- Rakel Liehu, Helene. WSOY, 2003

- Maja Lucas, Mor. En historie om blodet. C&K forlag, 2016

- Ulla-Lena Lundberg, Marsipansoldaten. Albert Bonniers förlag, 2001

- Ulla-Lena Lundberg, Is. Schildts & Söderströms, 2012

- Madame Nielsen, Invasionen. En fremmed i flygtningestrømmen. Gyldendal, 2016

- Bjørn Rasmussen, Ming. Gyldendal, 2016

- Charlotte Strandgaard: Katalog. Arena, 1966

- Kirsten Thorup: Indeni – udenfor. Gyldendal, 1967

- Kirsten Thorup: Erindring om kærlighed. Gyldendal, 2016

- Kerstin Thorvall: Det mest förbjudna. Bonnier, 1976

- Märta Tikkanen: Århundradets kärlekssaga. Trevi, 1978. The Love Story of the Century. Capra, 1984

- Linn Ullmann: De urolige. Oktober forlag, 2015

- Hanne Højgaard Viemose: Hannah. Gyldendal, 2011

- Hanne Højgaard Viemose: Mado. Forlaget Basilisk, 2015

- Bjørg Vik: Nødrop fra en mjuk sofa. Cappelen, 1966

- Ebba Witt-Brattström: Århundradets kärlekskrig. Norstedts, 2016

NON-FICTION

- Poul Behrendt og Mads Bunch: ”Autofiktion har knust modernismens facade”, Politiken, 28.04, 2015.

- Jørgen Gustava Brandt: ”A som i Vita”, Vente på et pindsvin, 1981.

- Suzanne Brøgger: Fri os fra kærligheden, 1973.

- Rita Felski: Literature after Feminism, 2003.

- Lise Garsdal: ”Jeg er feminist. Absolut”. Interview med Mara Le. Politiken, 09.03, 2015.

- Jon Helt Haarder: Performativ biografisme, 2014.

- Anne-Marie Mai: Hvor litteraturen finder sted, bd. III, 2011.

- Gerd Elin Stava Sandve: ”Linn Ullmann drømmer om et eget sted”. Interview, Dagbladet, 26.05, 2016.

- Hanne Højgaard Viemose: ”Forfatteraben”, oprettet 01.05, 2016.