Of seventeenth-century aristocratic Swedish women it has been said that: “when they with unaccustomed hands took up a pen, they loved to adorn their work with biblical phrases, however little high-flown the rest might be.”

Elof Tegnér makes this observation in an article on Sofia Juliana Forbus and her struggle to keep her property when faced with reduced circumstances and creditors. “En svensk adelsdam från slutet av sextonhundratalet” (A Late Seventeenth-Century Swedish Noblewoman), in Nordisk Tidskrift published by Letterstedtska Föreningen 1895.

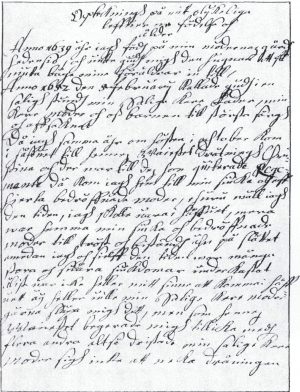

This biblical language did not come directly from the Bible itself, but to a far greater extent from prayer books and devotional literature. This was the literature via which the Bible stories were taught and interpreted, and this is the terminology that influenced the noble ladies who tried to express themselves in their national language. A short biographical text by Märta Berendes (1639-1717) gives a very clear illustration of this influence from religious literature. When recounting the main outline of her life story, her language and approach to the subject is borrowed from literature with which she was familiar. It is perhaps no coincidence that Märta Berendes inserts the description of her “unhappy life, birth and old age” into her voluminous prayer book, for that is the context in which it belongs.

That religious language had such a major impact was not only because spiritual literature was widely read, but also because it was by and large the only reading material.

We do not know much about Märta Berendes’ upbringing and education. When young she had been a lady-in-waiting to Queen Christina, and this might be where she had come into contact with the literary circles of the day. We know a lot more about one of her contemporaries, Beata Rosenhane (1638-1674), thanks to surviving diary-like records, snippets, poems and, in particular, letters.

“The men are now more famous than the women, but if it was the women who wrote history then they would definitely be the most important,” wrote Beata Rosenhane in a school essay, and went on to conclude: “as the lion says in Aesop’s fables: if the lion enjoyed painting, then you would see many more people being killed by lions than lions by people.”

Like her brothers, she received good tuition at home, and took the same lessons as them – although she did not learn Latin. Girls were generally made to concentrate on learning various forms of writing, primarily the art of letter-writing. The exercises were undertaken in the major European languages. If Beata wanted to write a little poem in Swedish, she had to ask for help. The school regulations introduced in 1649 had placed greater emphasis on the national language in state schools, but in private tuition at the homes of the aristocracy Swedish could not compete with, for example, French, which was the principal foreign language in use.

Beata Rosenhane’s reading material consisted not only of French novels, but also of works by the writers of antiquity; thus, from a language and literary point of view, she had a variety of role models. The majority of seventeenth-century women writing in Swedish, however, borrowed many language patterns from the devotional literature of the times. They of course mixed these patterns with their own forms of expression; as Märta Berendes wrote:

“Inasmuch as I have always lived in fear and terror, I have also tarried in adversity, and always one evil has offered its hand to the next, so that I have not had time to recover my breath after the one, before it has pleased my God to persist with a yet heavier one, such as has also come to pass in the present year […].”

The religious literature not only offered role models in terms of language use, however; reality, and the role of the individual in that reality, was interpreted, then as now, on the basis of, among other things, the literature read by that individual. In her autobiographical work, Agneta Horn identified with the suffering Job; like Leonora Christina, she saw her suffering as an imitatio Christi, a view that helped give both their lives meaning and render their conduct legitimate. “Many other tribulations and misfortunes, of which one may not speak, on account of both death and other unhappy events,” have occurred, writes Märta Berendes, but everything, both discussed and not discussed, is interpreted in a context of its meaning:

“Accordingly I am not aware of any year in our marriage in which it has not pleased God to let us feel that we are His children, since this is best understood through the Cross. The one cherished by God, must know that everything is for the best, this will be my comfort in all my wretchedness.”

In the autobiographical text there is a moment, a ‘now’ in which she is writing – 1676 – when Märta Berendes has been widowed for the second time. Following her brief marriage to Johan Sparre she had been married for fourteen years to Gustaf Posse, member of the Council of the Realm and High Court judge; in the course of these two marriages she had borne eleven children. She is now a widow, thirty-seven years of age.

Johan Sparre was son of the Johan Sparre who, according to Agneta Horn, had arranged for her brother and herself to be fetched from Stettin in 1631.

“We had thus to remain in Stettin right up until God suggested to Mr Johan Sparre that he should take pity on us, and he sent his carriage to Stettin to take us to Wolgast.”

“But inasmuch as it has always pleased the good Lord to allow me much and great anxiety, He has for the most kept my house under His paternal discipline, with illness sometimes in my dear virtuous poor husband and sometimes in me and the children.”

Gustaf Posse gradually becomes the central character in her life story, and when writing of his death Märta Berendes’ words overflow not only with grief, but also with trust in God:

“Inasmuch as this wicked world has already troubled me far too much, and this great wound has now been added, I believe, am certain, that I am not sinning against my God when I say with Saint Paul that I long to depart this place and be with Christ.”

Of Gustaf Posse we read that he: “in the name of the Council and Estates of the Realm, performed the sad ceremony, on the death of Karl X Gustaf in Gothenburg, of laying him and the regalia worn by him in the coffin, and thereafter he held, at the funeral in Stockholm in the presence of the Queens Christina and Hedvig Eleonora, an elegant and moving speech in his commemoration.”

Given that married women were quite simply a part of their husbands, it is natural that in writing her autobiography, in depicting her own life, a woman also depicts her husband’s life. However, Märta Berendes does not concentrate on the high-standing statesman and his many responsibilities, but on the man’s merits as husband in the home and, not least, his illnesses. On only one occasion does she touch on her own illnesses and mention some of her many experiences of childbirth. The whole family had been struck down with “stora mäslingen” (lit. big measles, presumably smallpox), and Märta Berendes is expecting what was to be her last baby: “yet the merciful Lord gave comfort to me at that time and gave me a breathing space before I was assailed by that which was the most arduous and difficult,” she writes. As in the family books, she notes deaths and births, but she finds meaning in illness and suffering from her reading of crucifixion piety in the devotional literature; this literature would also seem to have provided her with principles from which she could identify and select the most important events in her own life.

Märta Berendes’ brief autobiography does not have such a pronounced leaning towards the characteristic aspect of Agneta Horn’s or Leonora Christina’s autobiographies: defence of the self and discussion of obedience or fidelity. Nor is identification with Job explicit or particularly strong. Märta Berendes’ autobiography nonetheless comes from the same tradition of European literary life stories. The three extant autobiographies of seventeenth-century Swedish women were penned by Märta Berendes, Maria Euphrosyne and Agneta Horn. All three women came from the upper echelons of the nobility. Märta Berendes and Agneta Horn, who was ten years Märta’s senior, were linked by particularly strong ties of kinship, and their written life stories also bear certain similarities: in both cases the life story was written into a prayer book and coloured by the suffering they had undergone. Even though we are dealing with manuscripts, we must bear in mind the degree of public exposure a handwritten book of this kind received. You read one another’s books, wrote in them and copied out prayers or poems from them. Märta Berendes’ prayer book is a good illustration of what many prayer books looked like at the time. “En högt bedrövat änkas bön skriven ur min saliga svärmors Fru Ebba Oxenstiernas bok” (The Prayer of a Deeply Grieving Widow, Copied from my Blessed Mother-in-Law Mrs Ebba Oxenstierna’s Book) is included: different styles of handwriting and initials below the poems bear witness to contributions from many different pens. It would be interesting to know if Märta Berendes and Agneta Horn were familiar with one another’s written works.

Märta Berendes’ prayer book, like the autobiography, had at least one intended area of application. Gustaf Adolf Humble’s funeral sermon for lady-in-waiting Berendes in Stockholm’s Riddarholmskyrkan on 22 October 1717, and his added “true account” of her life, drew on the prayer book and autobiography for their source material. “On this sad occasion,” wrote Humble when retelling details of his mother’s death, “madam lady-in-waiting, seeking comfort, noted the following words in her prayer book: Now father and mother have forsaken me, now the Lord shall take me too.”

Gustaf Adolf Humble (1674-1741) was in the good graces of Dowager Queen Hedvig Eleonora, and in 1709 she nominated him court preacher and father confessor. One of his later appointments was that of Bishop of Växjö. Ever since the study trips of his young days, which included visits to Halle and Wittenberg, Humble had been a zealous opponent of Pietism. His treatise Of the Indecent Private Conventicles and Secluded Gatherings of a Few Inquisitive Persons was published in 1728.

As the Turtle Dove on a Branch

A twenty-nine-stanza song, “Een Annor Ny wijsa” (Yet a New Song), tells a tale from the time of the Thirty Years’ War. The song is kept in the Diocesan Library in Linköping, Sweden, in a collection designated Älfs visbok (Älf’s Songbook).

Samuel Älf was a well-known Latin poet and clergyman in Linköping. He died in 1799. He acquired the manuscript and presented it to the Diocesan Library in Linköping.

The manuscript is dated 24 July 1651, and the name concealed in the twenty-nine-stanzas’ acrostic might be that of the author. About Christina Regina von Birchenbaum we only know– apart from what the poem tells us – that her name appears in two prayer petitions from the late 1660s, in which she refers to herself as “poor Major Axel Paulj Liljenfeldt’s bereaved deeply grieving and wretched widow”. This Major Liljenfeldt did not die until 1662, and therefore the information in the poem, if it is read as autobiography, must relate to an earlier marriage.

An acrostic might spell the name of the writer or patron, or the central character in a poem. In this instance, a first-person narrator tells a personally-experienced story, and even though a reading of the poem as versified autobiography is far from obvious, it is nonetheless possible.

Christina Regina vom Birchenbaum, known as Finland’s first woman poet, writes about her lot in life. She was born “my mother’s only child” in Karelen – “without wishing to boast of myself, I was born in Karelen” – and was orphaned at an early age. Her father died when she was three years old, we are told, and she married young, to a soldier. “God willed it so that I became his flesh and blood.” But it was a time of war; her husband went missing in Germany and his wife searches for him there:

Journeying five-hundred (Swedish) miles (approx. 3,300 statute miles)

seemed to me but little toil.

In distress and faith I searched

for my beloved,

my distress grew far greater,

I sought and found nothing.

Fämhundrat mill at sträckia

mig tycktes mödha ring,

I sorg och troo iagh söckte

min hiärtans kiära mann,

min sorg thet fast föröckte,

iag söckte och intet fan.

However, a message gets through telling her that her husband had been killed in battle, and a three-year marriage turned to “bitter tears of lament” that later often pained her very heart, “yes, often still cause pain”. Three children were born to the couple, “three blossoms of our bed”. At the time of writing the poem, a “good nineteen years” have passed, two of these children have died, and the – possibly still alive – remaining daughter is married and living in another country:

Next to God, I found comfort

in you, my dear daughter.

Now you are taken from me,

gone across seas and sands.

God comfort me, who is grieved,

and you in a distant land.

Näst Gudh, min tröst iag hadhe,

hoos tig min dotter kiär,

nu ästu migh beröffwat,

utöfwer siö och sandh,

Gudh tröste mig bedröffwat,

och tig i fierran landh.

It seems as if the poem was written from bitterness or in defence, for the author tells of an incident that had occurred two years previously when a “fine lad” had come into her life after seventeen years of widowhood, and “love captured my mind”. She had been willing to give him her life and everything, but “the slyness of malicious tongues” caused him to leave her. And now, we learn from the poem, she is as “completely forsaken,/ as the turtle dove on a branch”.

Just under a century later, Mrs Nordenflycht uses the same image when, in 1743 after her brief but happy marriage, she wrote the poem “Den sörgande Turtur-Dufwan” (The Sorrowing Turtle Dove). In the symbolism of the time, the grieving turtle dove was emblematic of the lonely widow.

Christina Regina vom Birchenbaum’s poem opens in just the way a narrative poem – ever since antiquity – has been meant to open:

Christ, give me to sing

that which I have the will to do,

reign over my mind and my tongue,

for I will tell that which is to me

the greatest impediment

with other people, the hostility against me, best known

to God alone, and I know it well.

Christ giff migh at utsjunga,

som iagh haar wilian till,

regera modh och tunga,

ty iagh förtälia will,

hvad mig är fast till meena,

min wederwärdigheet,

for androm Gudh allena,

bäst kiändh, och jag wäll weet.

The rules prescribe this statement of subjects, and it is also found appropriate to ask for strength and help in the task of describing that which one has set out to do: “Lord, may what I here contemplate please you.” The poem is otherwise unsophisticated and is more like a simple song than the embellished poems of the Baroque. That does not mean, as is also clear from the excerpts above, that there is a lack of imagery. Of the transitory world which has little left to give, the final stanzas tell us: “under your sweet honey you bear bitter bile”. And the poem concludes with a prayer for release from this life and passage to the heavenly home and the heavenly bridegroom: “Ah, come, my dear bridegroom, come soon, Lord Jesus Christ.”

“Een Annor Ny wijsa” is not the only versified autobiography to have survived from the 1600s. One noted example is a poem written in 1644 by Karl Karlsson Gyllenhielm. Drottning Sofias visbok (Queen Sofia’s Songbook) contains four songs of an autobiographical nature written by Karin Ulfsparre, one of which opens: “I will begin a song about my unkind fortune”.

Karin Ulfsparre’s songs were thoroughly examined in an article by Sverker Ek in the Swedish literary journal Samlaren, 1917.

They were written before her 1635 marriage to Kristoffer Torstensson, and they describe her grief following the death of close relatives – and also, above all, of a man with whom she had been in love in her younger days: Jöran Ekeblad, who died in the summer of 1631 in Mecklenburg, Germany.

Jöran Ekeblad was the younger brother of Kristoffer Ekeblad, at the time active in Stiernhielm scholarship. Among his surviving papers there is an early version on Stiernhielm’s “Herkules” (first published 1658; Hercules).

And yet I must not complain

that fortune weighs heavy

in these years and days,

but [that it did] when I was young

and was meant to live

in the fullest of bloom

and in the greatest happiness

possible on earth.

Fortune changed quite quickly,

at the very moment

she disowned me.

I thought I should sink to the ground

because she could forsake me so

and so depart from me,

at the same time as she wooed

me with her guile,

as she still does every day.

En dåk iagh Eij må klaga,

öffuer lyckan är mig tungh

j dese år och dagar,

vthan då iagh var vng

då dett begynte bliffua,

som iagh bäst skulle leffua

vthij bästa flor,

och vtij glädie stor

som wara kunde på jordh

Rätt snart lyckan sigh wände,

vthij samma stundh

som hon migh aldrigh kiände

iagh tänkte siunka til grundh

för honn migh så mande suika,

och så jfrån migh wika

alt medh sin suik,

dårade hon migh,

så brukar hon än dageligh.

These songs, too, are more straightforward and heartfelt than grandiose and literary. Indeed, the writer even betrays doubt about whether they should have been written down at all:

Now I must soon make a decision

about this my song,

because it is not such

that I would venture to let many hear it,

for the one who has composed it

has not studied very much,

therefore no one may deride him.

Rät nu Beslut maste iagh snart

medh thenna min wisa giöra

Effter hon Ey haffuer sådan art

Iagh många tårs lata henne höra

för ty then henne haffuer samman sat

han haffuer jke mycket studerat

ty må honom jngen spåt giöra.

Parallels have been pointed out between these songs and Christina Regina vom Birchenbaum’s verse narrative, as well as with a few verses written in 1657 by Agneta Horn in her old friend Kristina Posse’s friendship album, complaining about her “blind fortune”. “And thus fortune plays its strange tricks on me year by year,” she wrote after her greatest loss, the death of her husband Lars Cruus.

Märta Berendes’ story of her life and the song “Een Annor Ny wijsa” reflect – as do Agneta Horn’s and Leonora Christina’s writings – the language models and interpretive patterns of the times. The texts are also, albeit on a smaller scale, examples of what Agneta Horn’s autobiography and Leonora Christina’s autobiographical descriptions bring into the spotlight: the many independent and resilient seventeenth-century women, brought up in an era of numerous wars and obliged to take care of family and property. Records of legal proceedings show how Märta Berendes was compelled to fight for her property in a probate court case that dragged on and on, and Karl XII’s greeting to the “old aunt” in his letters home to his sister are a greeting to the lady-in-waiting who had for many years held a responsible position in an ever-expanding Royal Household. It would be interesting to know more than the poem tells us about Christina Regina vom Birchenbaum, a woman who trawled the battlefields of Germany in search of her husband.

Translated by Gaye Kynoch